A few weeks ago at the Queers and Comics conference, I heard Alison Bechdel on a panel, talking about how her epic “Dykes to Watch Out For” got started.

“At first, I just wanted to see me and my friends in the world,” Alison said. “But after 25 years of doing that comic strip, I felt, ‘OK, we all know that lesbians are people, so let’s move on.'” The audience (including me) laughed appreciatively because, after over 25 years of activism, the fact that lesbians are people had thoroughly permeated every consciousness in the room.

But this was a room in New York, where dykes – and queers of all genders – can get legally married. Perhaps you’ve noticed that many places in the world are not New York. Even New York can be not-New-York, as queers are randomly harassed, beaten, and sometimes killed. You realize that whatever human status the law has given you can be taken away in a second by any rage-filled person you pass on the street.

By the same token, South Africa is not-South-Africa. Post-apartheid South Africa possibly leads the world in enlightened constitutions. Going beyond freedom of expression, it gives every South African the right to equal housing, employment, and health care. It is the first country on the planet to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation, and the first country in Africa to legalize gay marriage.

But real social and economic equality never came to poor Black South Africans. Vast inequality has borne vast hatred, often misdirected at women and queers. Beatings, rape, torture, and murder have become old news in world media, which report South African lesbians and transgender people being given “curative” rapes and often dying during the course of their “treatment.” Ignoring poverty and “not dealing with the corrupted system,” says Zanele Muholi, in a video interview by Human Rights Watch, “leads to many hate crimes.”

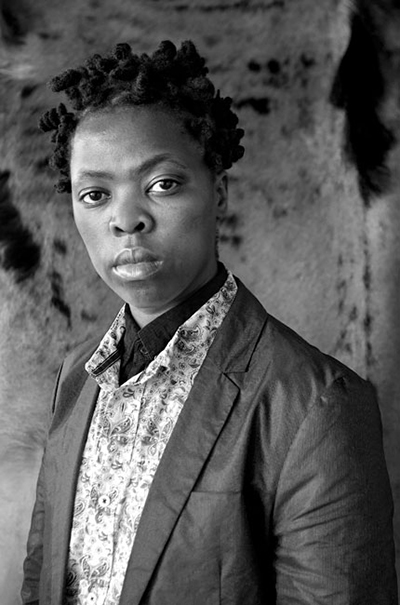

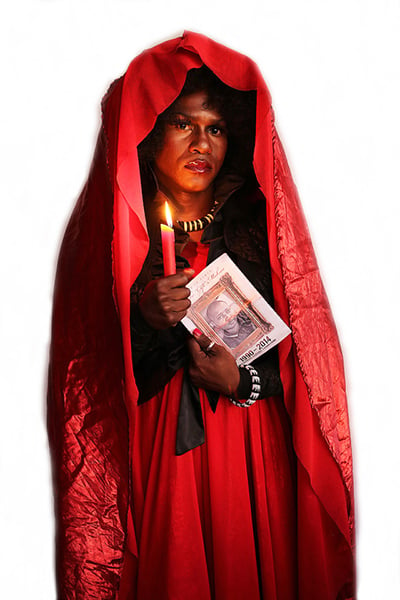

“Mourning Disebo Gift Makau.” (Image: ZANELE MUHOLI/ | COURTESY: BROOKLYN MUSEUM)Go up to the fourth floor and find “Isibonelo/ Evidence” (200 Eastern Pkwy., near Grand Army Plaza, through Nov. 1; brooklynmuseum.org). There, you’re greeted by a silent procession of black and white photos: 250 South African lesbians and trans people, whose portraits manifest one by one, each for five seconds, on a plain white wall. These are township people, whose eyes meet yours defiantly or sadly or joyfully. In their faces is a stark, full-on humanity, luminous with ordinary wisdom and psychic scars – physical scars, too. And you can guess where some of those scars come from.Muholi, a black South African lesbian, describes herself as a visual activist. She is responsible for a stunning exhibit of her photography and art installations now at the Brooklyn Museum.

“Mourning Disebo Gift Makau.” (Image: ZANELE MUHOLI/ | COURTESY: BROOKLYN MUSEUM)Go up to the fourth floor and find “Isibonelo/ Evidence” (200 Eastern Pkwy., near Grand Army Plaza, through Nov. 1; brooklynmuseum.org). There, you’re greeted by a silent procession of black and white photos: 250 South African lesbians and trans people, whose portraits manifest one by one, each for five seconds, on a plain white wall. These are township people, whose eyes meet yours defiantly or sadly or joyfully. In their faces is a stark, full-on humanity, luminous with ordinary wisdom and psychic scars – physical scars, too. And you can guess where some of those scars come from.Muholi, a black South African lesbian, describes herself as a visual activist. She is responsible for a stunning exhibit of her photography and art installations now at the Brooklyn Museum.

On a nearby wall, two hands hold a South African passport showing a page stamped “deceased.” This is the passport of Disebo Gift Makau, who was 23 years old when she was found half-naked with a hosepipe rammed down her throat. Her corpse lay across the road from her mother’s house.

Then there was Duduzile Zozo, raped and murdered in Thokoza, Gauteng, a toilet brush left inside her. And Noxolo Nogwaza, found in a ditch, her head crushed with a stone. And Eudy Simelane. And Girlie Nkosi. These are not statistics; they were members of Zanele Muholi’s community. According to a recent article in the British Telegraph, at least 32 lesbians have been murdered and raped in the past 15 years, though this figure is probably under-reported.

“Hate crimes have become a binding factor for LGBTI communities,” says Muholi in the HRW video. “And what are we doing about it? After funerals you go home and wait for another funeral? No, you have to document.”

Muholi was born in the Umlazi township of Durban in 1972 and lived her first 18 years under apartheid, the daughter of a maid in a white home. In the early 1990s, she became a reporter for a gay magazine in Johannesburg, only to find that the lives of black lesbians were not fully seen or included. So she headed back to the townships, to the black LGBTI people there, taking her skills as a photojournalist with her.

Most of the people Muholi photographs are younger, born after the politicizing 1980s and early ’90s, when queer activists of all colors worked against the apartheid regime. The South African LGBTI community now is united less by politics than by social media, so Muholi has invited queers – mostly black lesbians – to document their own lives and share them: weddings, parties, funerals.

“We all document the lesbian funeral, every person who has a cell phone with a camera,” she says. “It doesn’t matter what quality, all of us come together to make that document viral.”

To encourage community expression, Muholi has created Inkanyiso (inkanyiso.org), a brave and galvanizing organization, with its own website, that serves as a platform for her work and the work of her fellow LGBTI artists. Inkanyiso, a Zulu word meaning “illumination,” was also the name of Zanele’s own nephew who, in 2006, committed suicide at the age of 15.

“Love & Loss.” (Image: ZANELE MUHOLI/ | COURTESY: BROOKLYN MUSEUM)Back at the Brooklyn Museum, there are too many of Muholi’s penetrating images to absorb at one go. There’s a grid of black-and-white photo portraits; a blurry video of Muholi and her partner making love; photos and videos of joyous, raucous queer weddings. And, because the prospect of her own violent death has become part of her life, Zanele Muholi has installed a Plexiglas coffin, covered it with armfuls of flowers, and laid a framed photo of her own face inside on a white pillow.

“Love & Loss.” (Image: ZANELE MUHOLI/ | COURTESY: BROOKLYN MUSEUM)Back at the Brooklyn Museum, there are too many of Muholi’s penetrating images to absorb at one go. There’s a grid of black-and-white photo portraits; a blurry video of Muholi and her partner making love; photos and videos of joyous, raucous queer weddings. And, because the prospect of her own violent death has become part of her life, Zanele Muholi has installed a Plexiglas coffin, covered it with armfuls of flowers, and laid a framed photo of her own face inside on a white pillow.

So, of course, we at the Queers and Comics conference knew that lesbians are people. But some of the dykes Alison Bechdel so marvelously watched out for may not be able to move on just yet. Not in South Africa. And not here in the United States, where a simple phrase like “Black Lives Matter” has such trouble being accepted. Not here, where legalizing gay marriage has been used to wash pinkly over police shootings and drone strikes. We need to keep seeing and acknowledging the people who, for whatever legal or cultural reason, are still not considered human.

PS: “Shield and Spear,” a film about political art and activism in South Africa, is just out. It’s complex and provocative and Zanele Muholi’s in it – and you really need to see it: shieldspear.com.