Author Mark Bray dives into the debate over how confrontational the anti-fascist movement should be. In an excerpt from the introduction to Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook, he defines the scope of his inquiry.

Before analyzing anti-fascism, we must first briefly examine fascism. More than perhaps any other mode of politics, fascism is notoriously difficult to pin down. The challenge of defining fascism stems from the fact that it “began as a charismatic movement” united by an “experience of faith” in direct opposition to rationality and the standard constraints of ideological precision. Mussolini explained that his movement did “not feel tied to any particular doctrinal form.” “Our myth is the nation,” he asserted, “and to this myth, to this grandeur we subordinate all the rest.” As historian Robert Paxton argued, fascists “reject any universal value other than the success of chosen peoples in a Darwinian struggle for primacy.” Even the party platforms that fascists put forward between the world wars were usually twisted or jettisoned entirely when the exigencies of the pursuit of power made those interwar fascists uneasy bedfellows with traditional conservatives. “Left” fascist rhetoric about defending the working class against the capitalist elite was often among the first of their values to be discarded. Postwar (after World War II) fascists have experimented with an even more dizzying array of positions by freely pilfering from Maoism, anarchism, Trotskyism, and other left-wing ideologies and cloaking themselves in “respectable” electoral guises on the model of France’s Front National and other parties.

I agree with Angelo Tasca’s argument that “to understand Fascism we must write its history.” Yet, since that history will not be written here, a definition will have to suffice. Paxton defines fascism as:

… a form of political behavior marked by obsessive pre-occupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.

When compared to the challenges of defining fascism, getting a handle on anti-fascism may seem like an easy task at first glance. After all, literally, it is simply opposition to fascism. Some historians have used this literal, minimalist definition to describe as “anti-fascist” a wide variety of historical actors, including liberals, conservatives, and others, who combated fascist regimes prior to 1945. Yet, the reduction of the term to a mere negation obscures an understanding of anti-fascism as a method of politics, a locus of individual and group self-identification, and a transnational movement that adapted preexisting socialist, anarchist, and communist currents to a sudden need to react to the fascist menace. This political interpretation transcends the flattening dynamics of reducing anti-fascism to the simple negation of fascism by highlighting the strategic, cultural, and ideological foundation from which socialists of all stripes have fought back. Yet, even within the Left, debates have raged between many socialist and communist parties, anti-racist NGOs, and others who have advocated a legalistic pursuit of antiracist or anti-fascist legislation and those who have defended a confrontational, direct-action strategy of disrupting fascist organizing. These two perspectives have not always been mutually exclusive, and some anti-fascists have turned to the latter option after the failure of the former, but in general this strategic debate has divided leftist interpretations of anti-fascism.

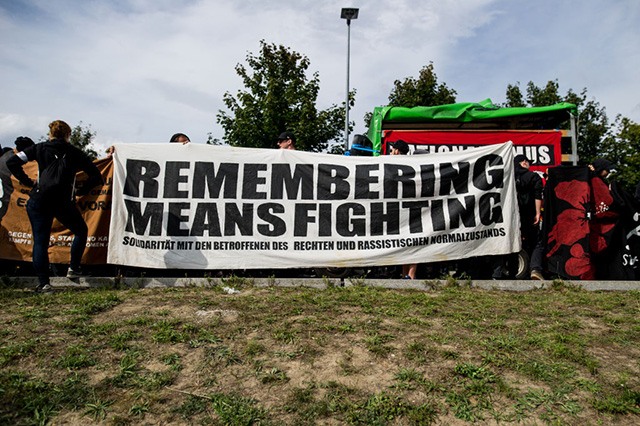

This book explores the origins and evolution of a broad anti-fascist current that exists at the intersection of pan-socialist politics and direct-action strategy. This tendency is often called “radical anti-fascism” in France, “autonomous anti-fascism” in Germany, and “militant anti-fascism” in the United States, the U.K., and Italy, among today’s antifa (the shorthand for anti-fascist in many languages). At the heart of the anti-fascist outlook is a rejection of the classical liberal phrase incorrectly ascribed to Voltaire that “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” After Auschwitz and Treblinka, anti-fascists committed themselves to fighting to the death the ability of organized Nazis to say anything.

Thus, anti-fascism is an illiberal politics of social revolutionism applied to fighting the Far Right, not only literal fascists. As we will see, anti-fascists have accomplished this goal in a wide variety of ways, from singing over fascist speeches, to occupying the sites of fascist meetings before they could set up, to sowing discord in their groups via infiltration, to breaking any veil of anonymity, to physically disrupting their newspaper sales, demonstrations, and other activities. Militant anti-fascists disagree with the pursuit of state bans against “extremist” politics because of their revolutionary, anti-state politics and because such bans are more often used against the Left than the Right.

Some antifa groups are more Marxist while others are more anarchist or antiauthoritarian. In the United States, most have been anarchist or antiauthoritarian since the emergence of modern antifa under the name Anti-Racist Action (ARA) in the late eighties. To some extent the predominance of one faction over the other can be discerned in a group’s flag logo: whether the red flag is in front of the black or vice versa (or whether both flags are black). In other cases, one of the two flags can be substituted with the flag of a national liberation movement or a black flag can be paired with a purple flag to represent feminist antifa or a pink flag for queer antifa, etc. Despite such differences, the antifa I interviewed agreed that such ideological differences are usually subsumed in a more general strategic agreement on how to combat the common enemy.

A range of tendencies exist within that broader strategic consensus, however. Some antifa focus on destroying fascist organizing, others focus on building popular community power and inoculating society to fascism through promoting their leftist political vision. Many formations fall somewhere in the middle of this spectrum. In Germany in the 1990s, a debate emerged in the autonomous anti-fascist movement over whether antifa was mainly a form of self-defense necessitated by attacks from the Far Right or a holistic politics, often called “revolutionary anti-fascism,” that could form the foundation of the broader revolutionary struggle. Depending on local contexts and politics, antifa can variously be described as a kind of ideology, an identity, a tendency or milieu, or an activity of self-defense.

Despite the various shades of interpretation, antifa should not be understood as a single-issue movement. Instead, it is simply one of a number of manifestations of revolutionary socialist politics (broadly construed). Most of the anti-fascists I interviewed also spend a great deal of their time on other forms of politics (e.g., labor organizing, squatting, environmental activism, antiwar mobilization, or migrant solidarity work). In fact, the vast majority would rather devote their time to these productive activities than have to risk their safety and well-being to confront dangerous neo-Nazis and white supremacists. Antifa act out of collective self-defense.

The success or failure of militant anti-fascism often depends on whether it can mobilize broader society to confront fascists, as occurred so famously with London’s 1936 Battle of Cable Street, or tap into wider societal opposition to fascism to ostracize emerging groups and leaders.

At the core of this complex process of opinion-making is the construction of societal taboos against racism, sexism, homophobia, and other forms of oppression that constitute the bedrocks of fascism. These taboos are maintained through a dynamic that I call “everyday anti-fascism.”

Finally, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that anti-fascism has always been just one facet of a larger struggle against white supremacy and authoritarianism. In his legendary 1950 essay “Discourse on Colonialism,” the Martiniquan writer and theorist Aimé Césaire argued convincingly that “Hitlerism” was abhorrent to Europeans because of its “humiliation of the white man, and the fact that [Hitler] applied to Europe colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved exclusively for the Arabs of Algeria, the ‘coolies’ of India, and the ‘niggers’ of Africa.” Without in any way diminishing the horror of the Holocaust, to a certain extent we can understand Nazism as European colonialism and imperialism brought home. The decimation of the indigenous populations of the Americas and Australia, the tens of millions who died of famine in India under British rule, the ten million killed by Belgian king Leopold’s Congo Free State, and the horrors of transatlantic slavery are but a sliver of the mass death and societal decimation wrought by European powers prior to the rise of Hitler. Early concentration camps (known as “reservations”) were set up by the American government to imprison indigenous populations, by the Spanish monarchy to contain Cuban revolutionaries in the 1890s, and by the British during the Boer War at the turn of the century. Well before the Holocaust, the German government had committed genocide against the Herero and Nama people of southwest Africa through the use of concentration camps and other methods between 1904 and 1907.

For this reason, it is vital to understand anti-fascism as a solitary component of a larger legacy of resistance to white supremacy in all its forms. My focus on militant anti-fascism is in no way intended to minimize the importance of other forms of antiracist organizing that identify with anti-imperialism, black nationalism, or other traditions. Rather than imposing an anti-fascist framework on groups and movements that conceive of themselves differently, even if they are battling the same enemies using similar methods, I focus largely on groups that self-consciously situate themselves within the anti-fascist tradition.

Copyright (2017) by Mark Bray. Not to be reposted without permission of the publisher, Melville House Publishing.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.