Two recent stories of climate change disasters mark the transition from spring to summer of 2013. The recent Black Forest fire in Colorado destroyed more than 500 homes and has been called, “the most destructive fire in Colorado history.” On the other side of the globe, last week, intense rain and flash floods brought massive destruction in Uttarakhand in northern India that has been called, the “Himalayan tsunami.” According to government estimates the death toll may cross 1,000, and thousands are still missing and tens of thousands stranded. Extreme weather events—floods, fires, droughts and hurricanes—in our time—are manifestations of climate change. Two recent studies, one published in the Geophysical Research Letters and the other conductedby the National Atmospheric Research Laboratory in Tirupati, India—have linked climate change to the recent increase in the frequency of very heavy rain and floods in India. And for sometime now scientists have been connecting the dots of climate change to the mega drought and the intense wildfires in the American southwest.

Stories of climate change however, come to us, one at a time, or a few might overlap, but rarely do we get a comprehensive look at once. If you live in New England, or visiting there this summer, you’ll have an opportunity to see—varieties of climate change impacts from around the world. The Museum of Science in Boston has just opened an exhibition, Climate Change In Our World: Photographs by Gary Braasch. It will run through September. Even if you don’t get to visit Boston, you’ll still be able to see Gary’s work through other media, as I’ll mention in a minute.

Twelve years ago, in early June, I had camped alongside Gary, on Caribou Pass, along the Kongakut River, in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. If you are lucky, almost exactly this time in June—20,000 caribou with newborn calves might surround your tent as you watch from the hills above—the spectacle of their return migration from the calving ground in the coastal plain to the southern wintering grounds. Gary, a well–known environmental photographer was already two years into his epic project, The World View of Global Warming. Later that month he photographed coastal erosion in Shishmaref. I published the photo in the anthology, Arctic Voices: Resistance at the Tipping Point that I edited. Gary had written the following caption for the photo:

Twelve years ago, in early June, I had camped alongside Gary, on Caribou Pass, along the Kongakut River, in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. If you are lucky, almost exactly this time in June—20,000 caribou with newborn calves might surround your tent as you watch from the hills above—the spectacle of their return migration from the calving ground in the coastal plain to the southern wintering grounds. Gary, a well–known environmental photographer was already two years into his epic project, The World View of Global Warming. Later that month he photographed coastal erosion in Shishmaref. I published the photo in the anthology, Arctic Voices: Resistance at the Tipping Point that I edited. Gary had written the following caption for the photo:

The Iñupiaq who inhabit the village of Shishmaref, Alaska, have survived here for generations but can’t halt the rising Bering Sea and the thawing of permafrost within the dunes. In 2002 residents voted to move their village to higher, more protected ground away from the ocean, giving up their traditional home, fishing, and sealing sites.

The US Environmental Protection Agency reports that the “increased coastal erosion is causing some shorelines to retreat at rates averaging tens of feet per year.” Today, some 160 communities in Alaska are threatened by climate change related erosion and several of those are facing immediate relocation. While the US government spends hundreds of millions of dollars in building data centers to spy on its own citizens and people of the world, no federal agency exists to appropriately address the concerns of the communities facing climate change related relocation. And while the US government puts in place a military justice system with the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), no legal framework exists to address climate justice lawsuits, like the historic onebrought against fossil fuel companies by the coastal Iñupiat community Kivalina in Arctic Alaska—a community facing immediate relocation. Scholars estimate that between 150 million and a billion people might face displacements due to climate change in the coming decades.

Gary continued his photographic documentation of climate change by traveling to remote destinations around the world. He photographed the decline of sea ice and glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica; and the receding Alpine glaciers in Alaska, Austria, China, Peru and Switzerland. He took before (1984) and after (2002) pictures of Mount Hood in Oregon, his home state—to illustrate that the glaciers on Mount Hood receded by more than 30% in those two decades. He traveled to communities that have been impacted by floods, including Bangladesh and Tuvalu—a small South Pacific island nation with only 12,000 inhabitants who live within a meter or two of high tide; and communities that have been impacted by droughts, including Kenya and China. He dove on the Great Barrier Reef and followed scientists into the field on four continents. He also paid close attention to the flora and fauna that are being impacted by climate change. He focused his lens not only on the large mammals like polar bears and penguins, but also on the smallest of creatures, like Krill and shorebirds, and the North American Edith’s checkerspot butterfly that has “moved north by about sixty miles and up the mountains by about 300 feet in the twentieth century.” He wrote the following caption to accompany a fabulous photograph of Krills he took in Antarctica, in which we see translucent invertebrates against a black background:

Gary continued his photographic documentation of climate change by traveling to remote destinations around the world. He photographed the decline of sea ice and glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica; and the receding Alpine glaciers in Alaska, Austria, China, Peru and Switzerland. He took before (1984) and after (2002) pictures of Mount Hood in Oregon, his home state—to illustrate that the glaciers on Mount Hood receded by more than 30% in those two decades. He traveled to communities that have been impacted by floods, including Bangladesh and Tuvalu—a small South Pacific island nation with only 12,000 inhabitants who live within a meter or two of high tide; and communities that have been impacted by droughts, including Kenya and China. He dove on the Great Barrier Reef and followed scientists into the field on four continents. He also paid close attention to the flora and fauna that are being impacted by climate change. He focused his lens not only on the large mammals like polar bears and penguins, but also on the smallest of creatures, like Krill and shorebirds, and the North American Edith’s checkerspot butterfly that has “moved north by about sixty miles and up the mountains by about 300 feet in the twentieth century.” He wrote the following caption to accompany a fabulous photograph of Krills he took in Antarctica, in which we see translucent invertebrates against a black background:

Krill, staple of the Antarctica food chain, maybe in shorter supply for predators, including whales and penguins, as a result of warming along the peninsula. A reduction in winter sea ice due to rising temperatures means less summer ice, under which Krill feed and develop.

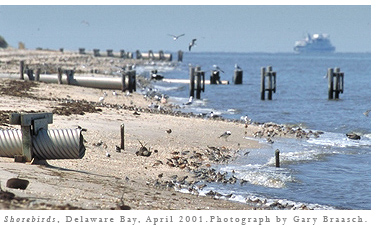

His photographs are not romantic pictures of nature but instead give us a more honest picture of our culture. Take for example, a picture in which we see dozens of shorebirds along a coast, some large pipes sit on the sand coming from the left, and a big ship in the upper right corner that looks like a cruise ship. He wrote the following caption for the photo:

On Delaware Bay in April a normal high tide narrowed the beach to a strip right below storm sewer outfalls during the annual migration of thousands of red knots, turnstones, and sandpipers. Chesapeake, San Francisco, Humboldt, and Willapa Bays, along with river deltas and smaller estuaries, are also experiencing an accelerating rate of sea level rise that is inundating many islands and intertidal habitats.

In 2007, the University of California Press published Gary’s book, Earth Under Fire: How Global Warming Is Changing the World. “For my son, Cedar, and his generation, and the generation to follow: May they see—may they be—the human promise fulfilled,” is the book’s dedication that echoes similar sentiments by many, including Dr. James Hansen. The book includes not only pictures with captions and essays by several scholars that address devastation, but also in a chapter titled, “Choosing a safer, cleaner, and cooler world,” he gives examples of resistance against destruction and how communities are coming up with local solutions to cope with climate change.

In 2007, the University of California Press published Gary’s book, Earth Under Fire: How Global Warming Is Changing the World. “For my son, Cedar, and his generation, and the generation to follow: May they see—may they be—the human promise fulfilled,” is the book’s dedication that echoes similar sentiments by many, including Dr. James Hansen. The book includes not only pictures with captions and essays by several scholars that address devastation, but also in a chapter titled, “Choosing a safer, cleaner, and cooler world,” he gives examples of resistance against destruction and how communities are coming up with local solutions to cope with climate change.

In 2009, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Washington, DC presented an exhibition with photographs from Earth Under Fire at their Atrium Gallery. Following year, Gary co–authored with Lynne Cherry a children’s book, How We Know What We Know about Our Changing Climate: Scientists and Kids Explore Global Warming that won sixteen children’s literature and science writing awards. His photographs have been published in magazines around the world, including Scientific American, Smithsonian, Time and Newsweek.

The Boston Museum of Science presentation is an updated and expanded version of the original AAAS exhibit. It includes eighteen 40×60 inch color prints with extended captions, and 100 digital images being displayed on a 40–inch screen. The digital presentation includes his recent photographs from Kiribati, Nepal, India, Alaska, the BP Gulf oil spill, and the American drought of 2012.

Most of you, including I, won’t have a chance to see the exhibit in Boston, but you can certainly visit the website of his remarkable ongoing project, World View of Global Warming, now in its 15th year. “In the Pacific Northwest, the oyster industry, with an $84 million yearly value and employing 3,000, is already seeing and reacting to the effects of unhealthy ocean water,” he writes on the ocean acidification page of the site. We see a beautiful abstract image of a twelve–day–old oyster larvae that he tells us is smaller in size than the period with which I’ll end this piece.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.