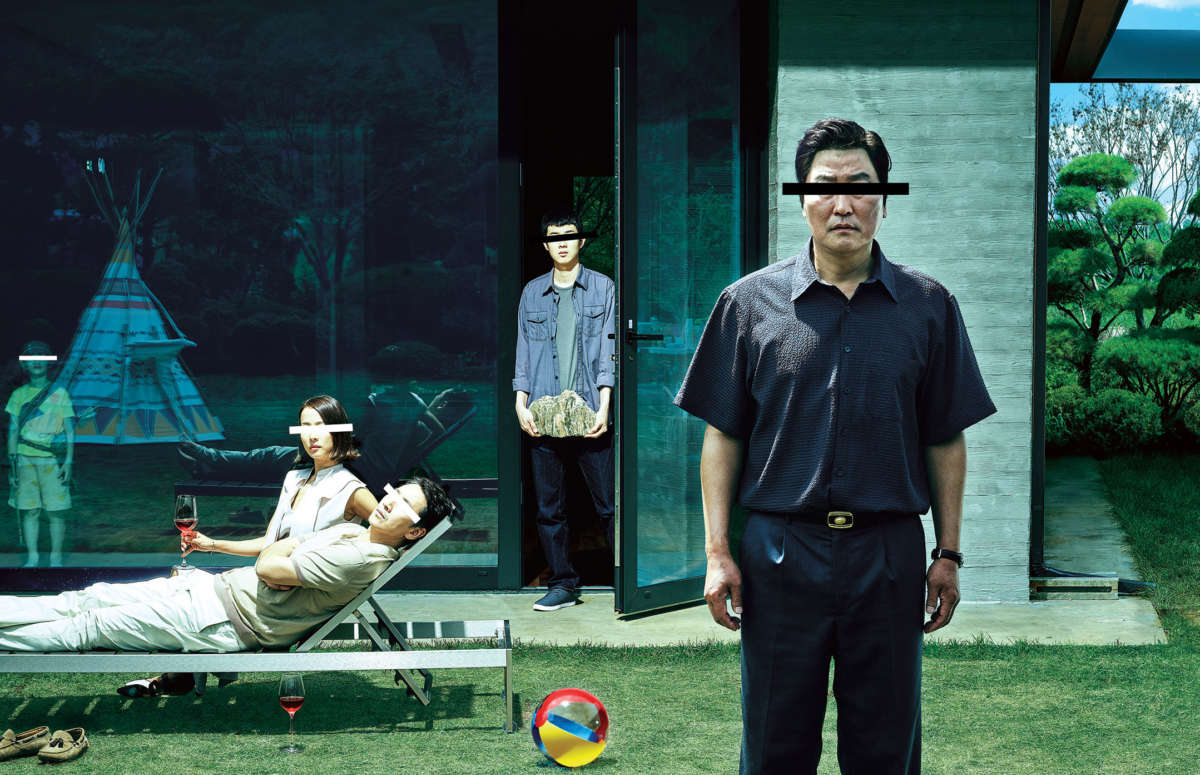

Bong Joon-ho’s recently released film Parasite isn’t the classical, one-dimensional depiction of poverty where the wretched of the Earth wait to be saved by those of superior intellect and resources. Most of the characters in the film are poor, very smart and forced by circumstances to be incredibly resourceful.

If there’s one thing that’s obvious when watching Parasite, it’s that our shared troubles don’t automatically unite us, even when we are actively working toward solutions to those problems. If we don’t share a view of those problems as originating in flawed systems — systems that we could unite to change precisely because they harm so many of us — then we’ll remain divided by those problems.

The opening of Parasite focuses on a family scrabbling to survive. The Kim family clearly care for each other, picking on each other in the ways of people who are close, while sitting at the family table in their half-basement apartment and half-heartedly trying to solve their financial problems. This scene, like so many others in a film that is partly dark comedy, showcases how people who have very little use humor to deal with life even when it’s tenuous.

Chung-sook is hard on her husband, Ki-taek, though not without affection. It quickly becomes clear, as she kicks her napping husband in the back in order to rouse him and half-teasingly ask him what they should do about their newest financial predicament, that their family, like so many poor families the world over, is matriarchal. Chung-sook is hard because she has to be, but also because she’s not bound by the patriarchal mores of the upper classes.

The siblings are slightly less hardened versions of their parents. The brother, Ki-woo, teases his sister, Ki-jung, asking her why she can’t get into art school after she expertly uses software to forge documents to help him get a job, but it’s clear that he admires her talent and thinks she should be honing it at school.

The Kim family help each other survive because they view themselves as a unit. However, they don’t extend that vision to people outside of their family. In their encounters with others struggling to survive, they try to cheat their way into jobs, even at the expense of those who have little more than themselves. Nor are they any better to those with even less, verbally abusing an alcoholic man who relieves himself regularly outside their window.

When one of them observes that the rich Park family, in whose employ they’ve enmeshed themselves, are “nice,” Chung-sook retorts that the Parks aren’t rich because they are nice, they are nice precisely because they can afford to be. Despite the Kims’ collective understanding that they aren’t poor because they are undeserving, they don’t necessarily view this as a reason to band together with other people who are poor.

Parasite is most effective at revealing how capitalism survives by causing people to prioritize their own immediate needs due to the urgency of those needs. The film is brimming with violence of all sorts, and that violence is enacted by poor people on other poor people as frequently as by the rich on the poor. True to the ever-unfolding nature of the film, there are several pivotal moments between the Kims and a family they’ve displaced in order to work for the Parks. Late in the film, there’s an epiphany of sorts about the Park patriarch whose money they all need, but even that is limited in scope, despite occurring during the movie’s most tense and violent scene.

Yet viewers can’t help but identify with the wheedling, cheating and, at times, brilliantly scheming working poor. Not only because they’re forced into their circumstances through the exploitation inherent in capitalist systems, but because their love seems more real, more grounded, and more tested by trials and tribulations than that of the rich characters. Critically, Parasite repeatedly gestures toward the missing awareness that would bring them together to organize around shared needs at the levels of community and class, rather than just family.

The film seems headed toward a conclusion multiple times in the last half-hour, some of the potential endings romantic and hopeful, some brutal and fatalistic. Because Parasite plays with so many genres over the course of the film, drawing on thrillers, slapstick and farce, among others, viewers are all the more easily driven to imagining conventional generic endings as each one seemingly presents itself as a possibility.

In concluding this way, it demonstrates that there’s real need — both psychological and material — to keep trying to imagine new futures until we arrive at one that works better for more people. This stands in contradiction to Ki-taek’s advice to his son, when he says you should never plan because then your plan can’t fail, an idea driven by years of despair.

Bong Joon-ho might be signaling that the only way out of the hackneyed endings of the past is through a future we haven’t yet fully imagined, a classless future that often seems impossible. But the film makes one thing clear: We won’t get there by reinforcing the divisions endlessly reproduced by the existing class system.

We have 9 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.