The recently released anthology Stories From the Center of the World: New Middle East Fiction (City Lights, 2024) collects short stories written by a variety of Arab, Iranian and Kurdish writers, as well as authors with varied identities and experiences, including people whose parents have been immigrants, and writers with multinational and multilingual backgrounds.

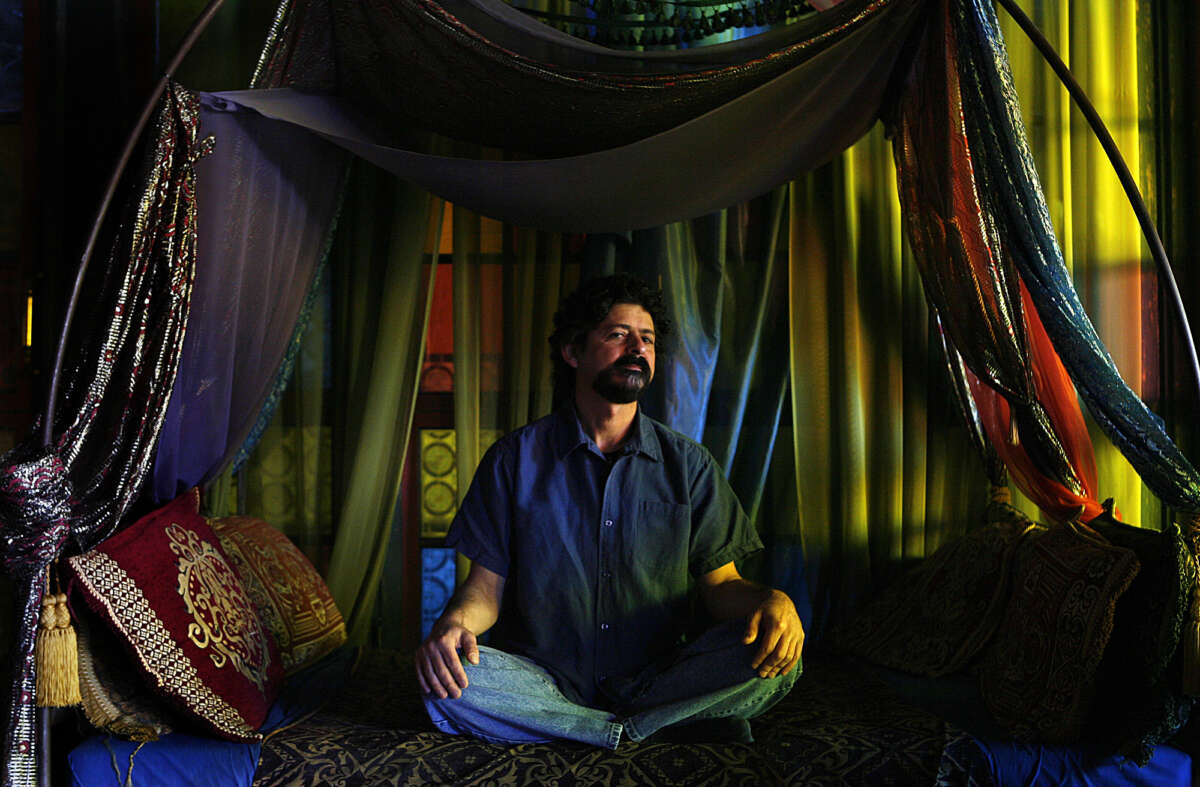

Anthology editor Jordan Elgrably, who identifies as Franco-American-Moroccan, has been engaged in cultural work based in diasporic Arab, Muslim and Middle Eastern communities since the ‘90s. With other Angelenos of Middle Eastern and North African heritage, he opened a cultural center in Los Angeles devoted to the region prior to 9/11. As the founder of The Markaz Review, he has published literature and political analysis from some of the most trenchant voices in the Arab and Muslim world. Elgrably is an outspoken advocate for the protection of writers and the right to free expression.

In this exclusive interview with Truthout, Elgrably explains the problem with the term “the Middle East” as coined by Western imperialists and discusses how Israel’s systematic murder of writers and poets in Gaza is part of a concerted effort to limit public knowledge about its crimes. The following transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Peter Handel: As Israel’s attack on Gaza rages, a record number of writers, journalists and poets have been killed. Why do you think writers have been targeted in this way, and what role have Palestinian writers, in particular, played in making the world aware of the plight of the Palestinian people?

Jordan Elgrably: Israel has unfortunately targeted Palestinian writers for termination since at least the early 1970s, when they eliminated Ghassan Kanafani. In 2022, an Israel Defense Forces sniper in Jenin assassinated Al Jazeera reporter Shireen Abu Akleh, a popular figure on the network, who was both Palestinian and American. Her murderer has gone unpunished, and it is a result of this kind of impunity that Israel has given itself license to deliberately take out Palestinian media workers, poets, writers, and other intellectuals in Gaza — including doctors and university professors. There have been reports of individuals in Gaza receiving threatening phone calls from Israeli military intelligence, who were then blown up in their homes, often with their family members. I believe the thinking is that by getting rid of people who write and speak about the ongoing genocide, Israel can limit public knowledge about its crimes in Gaza.

Arab and Muslim populations are often stereotyped in U.S. media. How do you think a collection of short stories and literature, in general, can help counter those stereotypes?

Israel has unfortunately targeted Palestinian writers for termination since at least the early 1970s, when they eliminated Ghassan Kanafani.

Our anthology of short stories lets the reader see Arabs, Iranians, and others from the region as real human beings, as three-dimensional people. Now, it’s a fact that Hollywood always needs villains. In the old westerns, they were Native Americans and Mexicans. In war movies they were Nazis and Japanese. After the fall of the Soviet Union, we lost our greatest enemy, and the evil Russians were soon replaced by Arab/Muslim terrorists. This has become such a trope that the dehumanization of Arabs and Muslims is rarely noticed and protested by U.S. film critics.

Examples of this — and there are hundreds — are Ben Affleck’s Argo and Clint Eastwood’s American Sniper. In both films, Iranians and Iraqis are utterly dehumanized, and I don’t recall seeing any mainstream media critics calling this out. In Argo, for instance, the Iranians speak Persian throughout the film, and there are no subtitles (until the very end), which has the effect of making the antagonists even more menacing, but also more two dimensional. In American Sniper, all the Iraqi characters are presented as “hajis” and brutes, including women and children. I could go on, but you get the point.

The first part of Stories from the Center of the World is titled “Exiles, Emigres, Refugee.” How do these stories give insight into the reality of Arab and Muslim diaspora?

I can’t think of a more mistrusted and maligned group of people than recent immigrants and refugees, whether in Europe or the United States. Politicians routinely paint these populations as a demographic threat, as people who are going to bring in crime and take your jobs. It’s such a caricature that one has to laugh. Our short stories are often written by people whose parents have been immigrants, or are still getting a foothold in a new country themselves. Or the writers have a multinational and multilingual background, often speaking a Middle Eastern language, such as Arabic, Persian, Turkish or Urdu, as well as English, which makes us eminently qualified to share our stories with western readers.

You’ve said that when it comes to the Middle East “the language of violence often drowns out the language of culture.” What do you mean?

The very terms “Middle East” and “Near East” were coined by western imperialists to capture a geographical zone to exploit for geopolitical reasons.

It’s the old media saw, “if it bleeds, it leads.” What I’m saying is that no, blood and war and internecine strife are not what we are all about. Conflict is a byproduct of much larger national and international issues, but meanwhile, people in Palestine, Egypt, Iraq, Iran, Algeria, et cetera, are busy leading their lives; they are getting educated, they are writing books and making movies; in other words, they are just like you and me, so stop looking at Arabs and others from the Middle East as violent Muslims, because this is a convenient stereotype. Do you look at all white Americans as psychotic killers, because all the mass school shooters are disgruntled white people?

Discuss how the book project came together. Were you looking to represent a writer from every country considered part of the greater Middle East (or the various communities located in Southwest Asia and North Africa)? Were there particular themes or topics that you wanted to address?

Stories from the Center of the World is the result of many years working with a variety of Arab and other Middle Eastern writers and poets, among them Rabih Alameddine, Reza Aslan, Raja Shehadeh, Laila Halaby, Diana Abu-Jaber, and others. These were writers whom I invited to present their novels, poetry books or nonfiction titles at our cultural center in Los Angeles. I also worked with a great number of peace activists on the Israel-Palestine issue, who brought out books, and so I’ve long been involved with different members of what I consider a like-minded and often progressive community, who see past the geopolitical bent of the “Middle East” and are innovating solutions, or who are presenting relatable human stories in their work.

What is problematic about using the term “the Middle East” or the “Near East”?

The very terms “Middle East” and “Near East” were coined by western imperialists. They are exonyms intended to capture a geographical zone to exploit for geopolitical reasons, terms used by outsiders to define others as they often do not define themselves; they are convenient catch phrases that continue to cause consternation today among those of us who are from the center of the world. (My heritage, by the way, is Moroccan and my paternal family has been in Morocco for at least a thousand years). Lebanese poet and translator Huda Fakhreddine calls the “Middle East” a trap — “a made-up thing, a construct of history and treacherous geography, the Middle East as an American trope, a stage for identity politics.”

So where do we go from here?

I would urge readers to think about the characters and the situations presented in Stories from the Center of the World, and really try to put themselves in the shoes of these protagonists. In fact, this is a good exercise in general: When you’re seeing images of people in Gaza enduring the Israeli onslaught, imagine yourself in the same situation. How would you deal with it, and what would you want outsiders to know? When you hear about fighting in any given country, see if you can imagine what it’s like to live through these situations. Because while the world is certainly diverse, there really is no “us and them;” whether you like it or not, we’re all in this together.

When there’s a war in the Middle East, it affects everyone. Just look at the mass demonstrations across the U.S. against what’s going on in Gaza, as an example. Look at how this horrible conflict has caused people thousands of miles away to lose their jobs, because their opinions might have offended the wrong people — even including university presidents. In fact, President Joe Biden may lose the November presidential election for how he has mishandled the crisis in Gaza. So don’t fool yourself: We are all interconnected, and it’s time we live like we feel it in our bones.

A critical message, before you scroll away

You may not know that Truthout’s journalism is funded overwhelmingly by individual supporters. Readers just like you ensure that unique stories like the one above make it to print – all from an uncompromised, independent perspective.

At this very moment, we’re conducting a fundraiser with a goal to raise $34,000 in the next 4 days. So, if you’ve found value in what you read today, please consider a tax-deductible donation in any size to ensure this work continues. We thank you kindly for your support.