Japan’s lost decades may have changed its society for the worse.

Twenty years of struggling with stagnation have left a mark, reports economics writer Charles Hugh Smith in an online article for AOL Daily Finance. He argues that the “consequences for the ‘lost generations’ that have come of age in the ‘lost decades’ have been dire.”

“In many ways, Japan’s social conventions are fraying under the relentless pressure of an economy in seemingly permanent decline,” he writes. He points out that young workers, having endured so many layoffs and seen their opportunities diminish over the past two decades, have become less competitive. Many perceive as pointless the years of schooling and hard work needed to compete for a dwindling number of elite, well-paying jobs.

In the United States, we’re well on our way to doing ourselves similar or worse damage. The good news is that more Americans are becoming aware of the risk of a Japanese-type trap. But not everyone.

Scott B. Sumner, a blogger and professor of economics at Bentley University in Massachusetts, recently attacked the idea that Japan is stuck in a deflationary trap at all. A trap is created when falling prices make consumers and businesses less willing to spend or invest because they expect additional declines in prices, which further depresses the economy.

Mr. Sumner insists that Japan deliberately fosters deflation: “I was under the impression that the Bank of Japan was an ultra-conservative bank, and liked mild deflation. Indeed I thought that was pretty widely understood. I guess not.”

He guesses right. I’m sorry to say that Japan is indeed caught in a deflationary trap. You can argue that the central bank should have done more to try to escape it — and I would — but persistent deflation is not its target.

The country is in this situation because conventional monetary policy has lost traction and the Bank of Japan isn’t willing to be more adventurous.

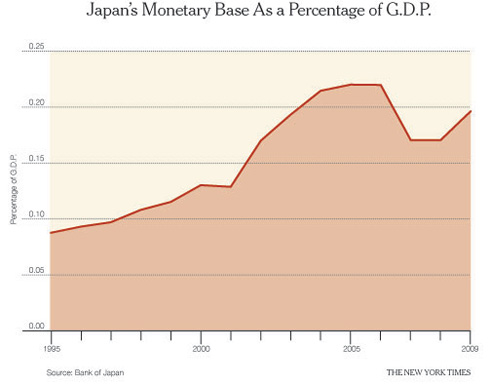

Look at the graph on this page describing Japan’s monetary base and you’ll see a huge increase from 1999 to 2003. This is the result of a quantitative easing policy — Japan’s attempt to end deflation by stuffing the banks full of reserves in the hope that the money would go somewhere. It didn’t.

Sumner continues: “Of course there are many other reasons why we know that Japan is not stuck in any sort of deflationary gap. They let the yen appreciate strongly during the midst of the great deflationary crisis of 2008-09. They dramatically reduced the monetary base in 2006 to prevent inflation.”

The graph reflects that reduction in the monetary base.

It doesn’t look all that dramatic to me, but in any case it was the result of the same kind of debate that’s currently going on in the United States: some people at the Federal Reserve are just itching to exit from unconventional monetary policy.

Backstory: Trapped for Decades

As economic recovery in the United States continues to languish, some economists are warning of the increasing possibility of a “Japan-style” period of deflation — a downward spiral of low prices that can be difficult to reverse once it starts.

Behind these fears lies compelling data.

In a report released Aug. 9, Goldman Sachs lowered its growth estimate for Japan from 1.7 percent to 1.4 percent and for the United States from 2.5 percent to 1.9 percent.

In both cases Goldman cited reduced government stimulus spending as the main reason for the downgraded outlook. Other reports have shown dips in consumer spending, home sales, factory orders in both countries and, in Japan, a reduction in industrial output and an increase in the unemployment rate.

While deflationary fears are relatively new to the United States, Japan has been struggling with stagnant growth for almost two decades — long enough that an entire generation has no memory of a thriving economy, and Japanese society and culture are beginning to change. In the best-selling book “The Herbivorous Ladylike Men (Who) Are Changing Japan,” author Megumi Ushikubo links these economic troubles to youths’ opting out of the traditional course of career advancement in Japan.

With strong disincentives to professional achievement, some young men are choosing to live at home and remain single, rather than pursue college education and corporate jobs.

This may be contributing to the widening income gap between older workers, who are more likely to hold lifetime corporate jobs, and younger workers, who must survive on low-paying temporary work. The educational disparity could erode Japan’s economy further as the older generation retires and the younger generation tries to fill its shoes.

Truthout has licensed this content. It may not be reproduced by any other source and is not covered by our Creative Commons license.

Paul Krugman joined The New York Times in 1999 as a columnist on the Op-Ed page and continues as a professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton University. He was awarded the Nobel in economic science in 2008.

Mr Krugman is the author or editor of 20 books and more than 200 papers in professional journals and edited volumes, including “The Return of Depression Economics” (2008) and “The Conscience of a Liberal” (2007).

Copyright 2010 The New York Times.

We have 10 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.