A lifetime of work and personal experience in drug treatment has led Sheila Vakharia to become committed to harm reduction — a framework that offers skills and strategies to those engaging in high-risk activities, including but not limited to drug use, to keep them and their communities safe.

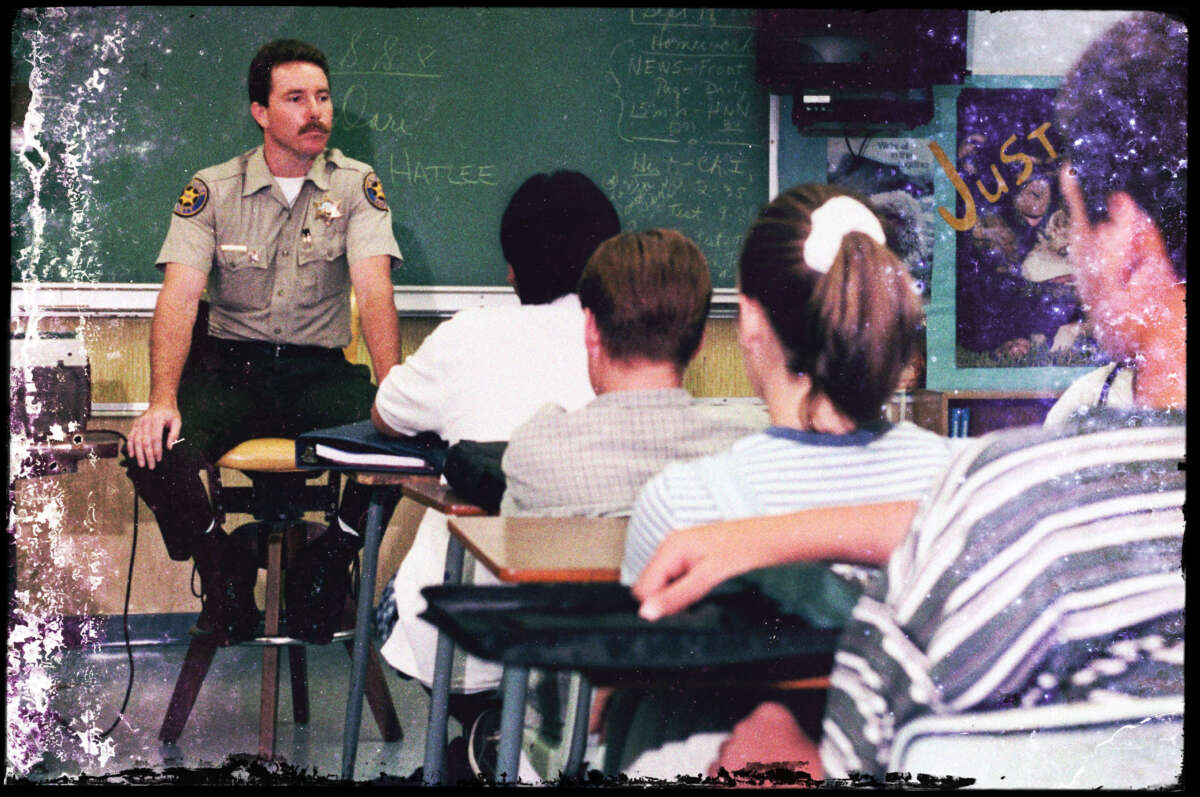

Harm reduction stands in sharp contrast to the dominant current drug treatment paradigm, which revolves around abstinence-only drug prevention education and abstinence-based drug treatment programs.

In working on harm reduction, Vakharia, who is currently the deputy director of research and academic engagement at the Drug Policy Alliance, told Truthout that she has witnessed a gap of support unavailable to people who start or continue to use drugs, or what she refers to as “the harm reduction gap.”

Vakharia’s forthcoming book, The Harm Reduction Gap: Helping Individuals Left Behind by Conventional Drug Prevention and Abstinence-only Addiction Treatment, outlines her journey growing up in Ronald Reagan’s “Just Say No” era, leaving traditional 12-step abstinence-only treatment for a syringe service program as a social worker and becoming an expert in harm reduction. Consider it a primer on what harm reduction is and isn’t, including fundamental tenets and beliefs as well as misconceptions. The book tackles important drug policy questions like the war on drugs, treatment programs and what causes addiction.

The Harm Reduction Gap is set to be released on February 9, 2024, by Routledge. Truthout contributor Adryan Corcione sat down with Vakharia to discuss the book.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and condensed for length.

Can you explain what you see as the problem with mainstream approaches to addressing substance use?

Our current continuum of strategies to address substance use in our communities consists of two extremes: abstinence-based drug prevention education — which tells young people and youth across the nation “don’t do drugs” — and abstinence-based treatment for people who did not listen to the abstinence-based education, who went on to use substances and perhaps developed a problem. There’s a gap in our current system because there isn’t support available to people who choose to start or continue using drugs.

You have a professional background in social work, drug policy and harm reduction with 15 years of experience. What’s going on in the world currently that sparked you to write this book?

What motivated me to write this book was the current moment we’re in amidst this overdose crisis. We provide abstinence-based drug education to young people while relying upon a restrictive, hard-to-access, unaffordable, one-size-fits-all treatment approach — and people continue to die. There are solutions we could be using informed by harm reduction research and expertise — not the mainstream — that are expanding in certain communities but are still continuing to face backlash. Others are illegal, inaccessible and unavailable in many parts of our country.

While certain people are learning more about harm reduction, the majority of people across the United States are still unaware that these options are available, that these kinds of services could be provided, that they could be educating themselves in their communities on how to stay safe in a world with drugs. This current overdose crisis, the ramping up of punitive approaches, the broader lack of awareness that there are harm reduction options available that could be developed that could be expanded, to me show the urgency and need for a book like this.

You start the first chapter with a personal anecdote. At 5years old, you saw so many “don’t drink and drive” PSAs, but didn’t realize the context was alcohol, so you frantically panicked when your dad drank coffee as he unlocked his car door. Could you talk about why it felt important to include these kinds of personal stories and how they connect to a more universal experience of growing up (and being indoctrinated) amid the war on drugs?

I understood that if I wrote a book for this moment, people had to read it. I approached this project with the understanding that I needed regular everyday people — voters, community members, family members, neighbors, elected officials, journalists, students — from all walks of life to feel like my book was interesting, engaging, relevant and useful to their lives. I needed to put myself at the center of it because I wanted to show that not everyone’s born a harm reductionist.

Most of us are steeped in stigmatizing and oftentimes problematic messages around drugs. I think of myself as an example of an average person who grew up steeped in these messages, but whose life experiences accumulated to have me start questioning: “Is this the best way to approach a behavior that hundreds of millions of Americans engage in across the nation every day?” In reflecting on my own process, I hope to engage readers in reflecting on their own experiences and invite them to consider that if I could grow up seeped in these messages and come to a different place of understanding, potentially they could, too.

Harm reduction stands in sharp contrast to the dominant current drug treatment paradigm, which revolves around abstinence-only drug prevention education and abstinence-based drug treatment programs.

You discuss medicalization in your chapter on the war on drugs. Can you briefly define medicalization as it relates to drugs and expand on how medicalization contributes to the harm reduction gap?

To medicalize a drug is to categorize it as a substance for treating or managing certain symptoms. Because of those potentials in certain dosages under the directive of a medical professional, this use is sanctioned, legal, paid for and available to certain people without fear of arrest, incarceration or punishment. Medicalization creates categories of medical use versus all other forms of use.

While medicalization is a great tool for allowing access to certain substances, unfortunately, it still excludes a lot of people. Medicalization can narrow a drug’s purpose when actually people may find off-label uses. Prescription stimulant drugs have approved uses for ADHD and narcolepsy; however, doctors are also prescribing these medications for long COVID. The way we write guidelines doesn’t acknowledge that. For some people, maybe there isn’t enough research or evidence — even though others say it helps brain fog and other long COVID symptoms.

Medicalization doesn’t acknowledge the broader biases that exist in our health care and medical treatment settings in terms of who is deemed a worthy patient whose symptoms are understood and appropriately diagnosed. The undertreatment of pain among Black people and other people of color is often driven by cultural and linguistic barriers between providers and patients, but also false beliefs that for instance, Black people have higher tolerances for pain, women over exaggerate their pain or people with disabilities may not experience certain forms of pain.

Certain people are often excluded from the privilege of being viewed as patients due to a matter of money or private insurance status. Some people can’t pay out of pocket for an off-label prescription if their insurance doesn’t have a billing code for long COVID.

You spend some time rehashing what harm reduction is and isn’t. Why is it important to devote time to discussing what harm reduction isn’t?

As a term used in the broader zeitgeist, there’s always a concern that people may misunderstand or misuse it. I’ve heard harm reduction start to be misused in a variety of settings. I’m concerned about the mainstreaming of harm reduction and its broader roots being lost because some people think that harm reduction is just simply a set of tools, rather than a broader philosophy and understanding of high-risk practices, human behavior, autonomy and self-determination.

What are some misconceptions people have about harm reduction and how are those misconceptions harmful?

Unfortunately, calling 911 for medical assistance during an overdose is often synonymous with calling the police because they often show up before EMTs during these calls in most parts of the country. This can mean that officers — who have been trained to view drug use as a crime and people who use drugs as criminals — are now expected to respond to an overdose as a medical emergency, rather than as evidence of a crime. Although police across the nation are getting trained in overdose response, there is research to suggest they are reluctant to take on this role and they still have negative attitudes towards people who use drugs.

You mention that harm reduction isn’t just the sum of its tools and strategies, that harm reductionists also advocate for public health and safety policies, such as affordable housing, fair living wages, criminal justice reform, social safety net funding, health care access, and more. Can you expand on why harm reductionists advocate for these policies, even when they’re not directly tied to drug policy?

We understand the safer, the healthier, the better our community’s well-being, the safer drug use will be and the safer people who use drugs will be. As long as people do not have stable housing, food, emotional support, health care, people will be more likely to experience or engage in risky drug use. When people are well, regardless of behaviors they engage in, they will be more resilient. They can offset potential harms of drug use and can maximize the benefits.

Do you see harm reduction as something opposed to treatment?

We’re having these debates around treatment. How do we get everyone into treatment? Should we be funding harm reduction when we could be funding a treatment instead? Oftentimes people create this false dichotomy of either harm reduction or treatment, or that harm reductionists are fundamentally opposed to treatment.

I hope that my book helps people understand that treatment, including abstinence-based treatment, can be helpful — and that this does not take away from the need for harm reduction in communities. The reality is that only 10 percent of people with addictions will receive treatment in any given year and the remaining 90 percent of people with addictions will not pursue formal treatment because they do not want it, cannot afford it, cannot find it or cannot adjust their lives to accommodate our high threshold system. Harm reduction could provide them with an alternative to help keep them safe. Beyond this, the majority of people who use drugs do not have addictions but could benefit from tools, support and education to stay safe while using drugs — they are ideal candidates for harm reduction services.

We should see harm reduction as a safety net for people who started treatment but who didn’t finish it. Some portion of them dropped out, were kicked out or terminated because they continue to use drugs, or they struggled with strict requirements. Some get locked up because they don’t finish a mandated treatment course and don’t have another source of support. Not everyone will finish their treatment episodes. Harm reduction should be part of that backup plan.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.