On July 1, Emancipation Day, Dutch King Willem-Alexander apologized for the nation’s history of colonial slavery in both the East and the West. The apology is monumental, especially for descendants of the enslaved living in the Netherlands, who have fought hard for this recognition and who continue to face serious systemic racism across Dutch institutions, from education, to housing, to the job market and law enforcement.

“The horrific legacy of slavery remains with us today. Its effects can still be felt in racism in our society,” the king acknowledged.

However, a careful read of king’s words shows he failed to accurately or appropriately apologize for the role his family played in Dutch slavery. He claimed his family were simply bystanders, when they were in fact perpetrators. The Dutch played a central role in starting slavery in the United States, but the Dutch monarch’s omissions erased important African American history.

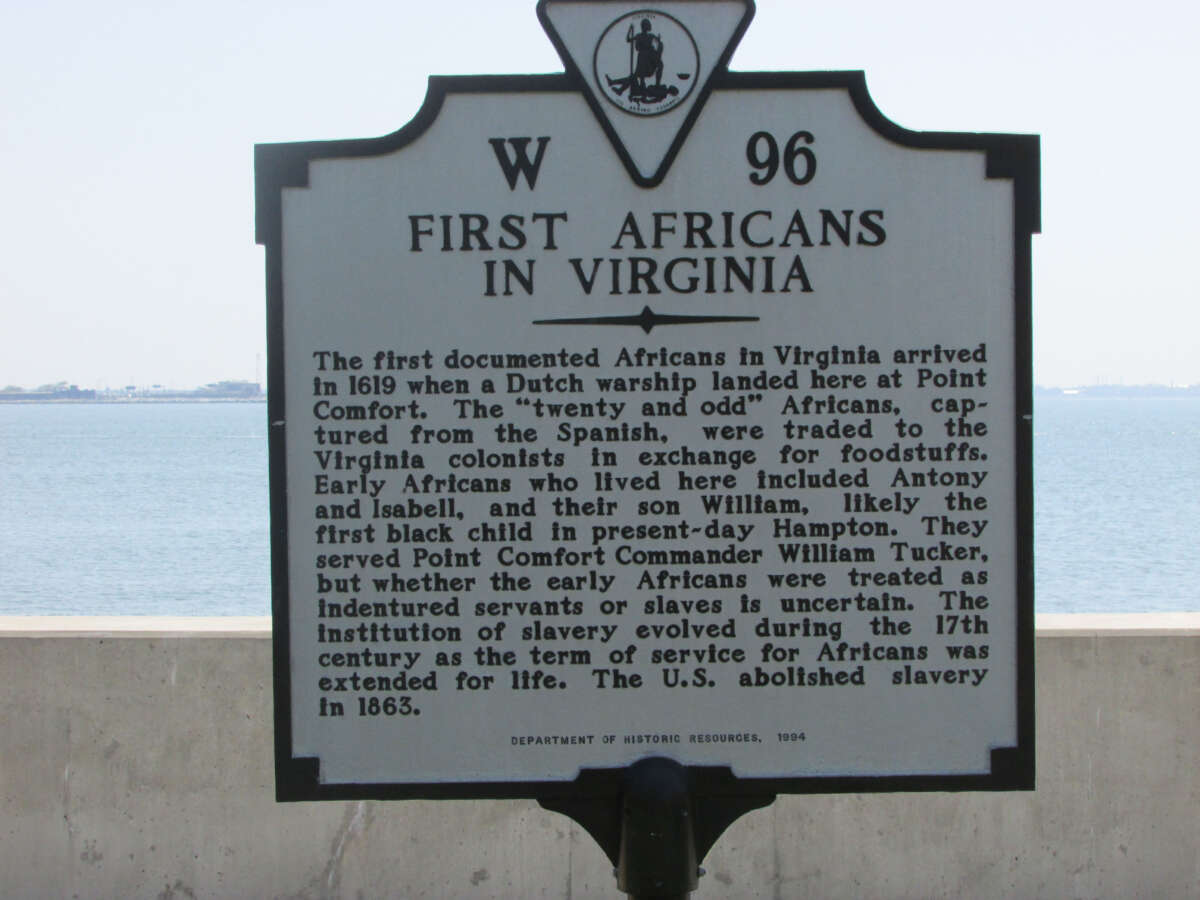

1619

Dutch slavery did not start in the Atlantic. As described by Dutch investigative journalist Leendert van der Valk, it started in 1595 in Madagascar with the chaining of two teenagers the Dutch named “Madagascar” and “Lourens,” who were shipped across the Indian Ocean to what would become known as the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia.

A generation later, in 1619, another Dutch/British ship, this time sailing west, arrived on the shores of Virginia, carrying the first African people in North America. Two of the abducted people on the boat, “Isabella” and “Antonio,” would later have a child, William Tucker, the first African American.

An Orange Signature

Described in an earlier piece by Van der Valk, the Dutch/British ship also carried a “letter of marque,” a document that legalized the human “cargo” looted from the Portuguese in the Caribbean. The letter bore the signature of Maurice of Orange, ancestor of King Willem-Alexander. In other words, the system that would become U.S. slavery started with an Orange signature.

King Willem-Alexander neglects to tell this story. Starting his speech by joining the Dutch government’s earlier apology for slavery, made in December of last year, he describes his family’s involvement as follows:

“Slave trade and slavery are acknowledged as crimes against humanity. The stadtholders and kings of the House of Orange-Nassau did not take action against this. They acted within the framework of what was legally permissible at the time. But the system of slavery illustrated the injustice of those laws.”

Moral relativism like “slavery was normal back then,” even if qualified as an injustice, is inappropriate in a slavery apology, betraying even the perspective of the oppressor. But what’s more, the Orange family did more than simply “not take action” against slavery. They were the foundation of that system in the U.S. With 1619 as the start of race-based bondage in the U.S., the king’s erasing of this active guilt not only contradicts critical race theory and the idea that the U.S. system of chattel slavery that began in 1619 was backed at the highest institutional levels, but also erases a defining part of the African American experience.

Planting a Tree

Artist-activist Quinsy Gario, who started a cultural revolution in the Netherlands by challenging the tradition of Dutch blackface, has been one of the few people to question the motivations behind the king’s apologies, asking on Twitter why he hasn’t apologized to African Americans or to South Africa. Dutch colonists settled in South Africa since 1652, where, as a continuation, Amsterdam-born Hendrik Verwoerd became the architect of Apartheid in the mid-twentieth century.

In 2015, on his first state visit to the U.S., King Willem-Alexander neither visited the site of the first slave ship’s arrival in 1619 in Virginia, nor met with the Indigenous Lenape tribe to acknowledge the stealing of land and the installation of the “New Netherland” scalping currency that pitted tribes against each other at a standard price-per-enemy scalp.

Instead, the royal couple came to Michigan, the world of Dutch-U.S. billionaire power, to meet people with names like DeVos (of the Trump administration) and Van Andel (of Amway). There, in the land of the Odawa (“traders”), the king and queen planted a tree on Dutch settler-colonial land, without acknowledging the Dutch role in the Native genocide, treating the U.S. as a neocolonial trading ground.

An Update to Slavery

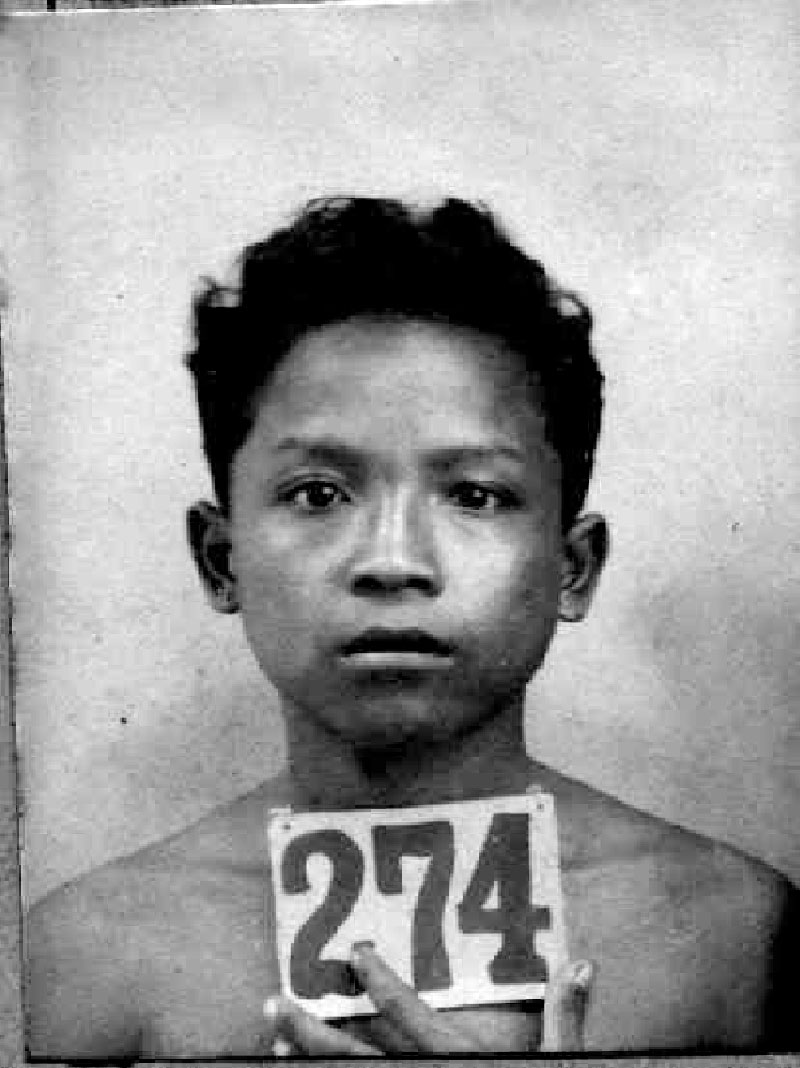

I, co-author Christa Wongsodikromo, am a descendant of Indigenous Javanese survivors of Dutch colonialism and colonial boarding schools in the Dutch slave colony of Suriname. I was born after Suriname’s independence from the Netherlands in 1975, the first generation that has not lived under Dutch colonialism.

I feel the danger that looms behind King Willem-Alexander’s words. Systems of oppression will update themselves and continue their exploitation in ways that traumatized my family. After the abolition of transatlantic slavery, the Netherlands replaced its slavery economy in Suriname with an indentured labor system.

As part of this update, the Netherlands kidnapped my great-grandparents from Java (Indonesia) in 1928, and shipped them across the globe to work on the plantations in Suriname. Two of my great-grandparents were children at the time but were registered as adults to legalize their forced labor, part of the “permissible framework” of the time.

Just prior to the Netherlands government’s earlier slavery apology in December, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte stated that apologies will not follow with financial reparations, and that the Netherlands will not be paying “years after the fact.” With this, he denied the continuing legacy of slavery and colonialism today.

Institutional Racism

Less than a week after the king’s apologies, on July 7, the Dutch government stepped down, for the second time in 2 years, over a racism-related issue. In 2021, the government collapsed amid what is known as the “child care benefits scandal”, where the Dutch tax authority was found to have used racist algorithms. In the most recent crisis, the ruling party of the prime minister put up barriers to family reunification of predominantly Middle Eastern refugees. The two events, both affecting children, are emblematic of the only country in Europe that has institutionalized the distinction between “black” and “white” schools.

Institutional racism happens easily when a country has not come to terms with, and continues to erase, centuries of colonial power abuse. Now, King Willem-Alexander is doubling down by erasing African American history. A meaningful solution will come when the U.S. and the Netherlands work together toward truth and reconciliation.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.