Spencer Ellison, whose unarmed father was shot to death by police officers in his own home, addresses attendees at the City of Little Rock’s dedication of a public bench in memory of his father on November 4, 2016. Ellison and his brother brought a federal civil rights lawsuit and won the largest monetary settlement ever reached in a Little Rock police case, in addition to an official apology from the city. (Photo: Flint Taylor)

Spencer Ellison, whose unarmed father was shot to death by police officers in his own home, addresses attendees at the City of Little Rock’s dedication of a public bench in memory of his father on November 4, 2016. Ellison and his brother brought a federal civil rights lawsuit and won the largest monetary settlement ever reached in a Little Rock police case, in addition to an official apology from the city. (Photo: Flint Taylor)

It’s time to map out strategies to combat Donald Trump’s support for police violence. The president-elect has promised to redouble racist stop-and-frisk, to support reactionary police unions, to further militarize police departments, to attack Black Lives Matter activists, to round up undocumented workers and to support the oil and gas companies that are attacking Indigenous Water Protectors on the front lines in Standing Rock. Meanwhile, Sen. Jeff Sessions — Trump’s pick for attorney general — will no doubt seek to dismantle the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice and make the aggressive investigation of police departments for patterns of racially motivated violence a thing of the past.

Amid all this, much of the battle must be fought locally, in cities and towns across the country. Even as we back those who are on the front lines of acute, present-day struggles, we must also pursue ongoing struggles for reparations in the wake of injustice.

On the eve of the election, in a deeply red state, the city of Little Rock, Arkansas, took a small but significant step in furtherance of this goal by dedicating a memorial bench to a victim of police violence named Eugene Ellison.

Ellison was a 67-year-old African American man who resided in the Big Country Chateau Apartments on the west side of Little Rock. He lived alone and walked with a cane. He had his door open on a cool December evening in 2010, minding his own business, when two white Little Rock police officers working security at Big Country decided to enter his apartment, despite his protests that he did not need help and wanted to be left alone. When he verbally resisted their entry, a scuffle ensued, he was maced, and when he refused to submit, one of the officers fatally shot him from the apartment doorway. The officers claimed that he had raised his cane and started to swing it toward them, but the physical evidence, the paths of the fatal bullets, and another officer on the scene completely discredited that story.

Troy Ellison, son of police shooting victim Eugene Ellison, speaks at the City of Little Rock’s dedication of a public bench in memory of his father on November 4, 2016. (Photo: Flint Taylor

Troy Ellison, son of police shooting victim Eugene Ellison, speaks at the City of Little Rock’s dedication of a public bench in memory of his father on November 4, 2016. (Photo: Flint Taylor

Ellison’s son Troy (now a lieutenant in the Little Rock Police Department) and his other son, Spencer (a former Little Rock Police Department detective and now a college professor in Texas) brought a federal civil rights lawsuit against the officers, the city of Little Rock and Big Country Chateau Apartments. The suit alleged that Ellison’s constitutional right to life under the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution had been violated. It also alleged that his death was caused by the practices and customs of the Little Rock Police Department, which included a willful failure to discipline brutal cops, a police code of silence and woefully deficient hiring and training practices. The family’s lawyers amassed a wealth of evidence in support of its claims, and in 2014 requested that the Justice Department investigate the Little Rock Police Department for its unconstitutional practices as documented in the evidence uncovered in the suit, a request that the ACLU renewed in 2015. When the federal judge refused to dismiss the case, the city of Little Rock appealed his ruling, but the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the Ellison family and the case was returned for trial.

In May of this year, the case was set for trial and the trial team, which was headed up by California attorney Mike Laux, entered into settlement discussions with the city. An attorney named Doris Cheng and I were also on the trial team. Guided by the Chicago reparations for police torture experience, the family and the lawyers sought to combine a monetary settlement with some of the non-monetary elements obtained in Chicago. Only days before the trial was set to begin, a settlement was announced. It was the largest monetary settlement ever reached in a Little Rock police case. It came with an official apology from the City Manager, a memorial bench that would honor Ellison, and a public dedication of the bench.

Alongside the large monetary settlement won by the family of police violence victim Eugene Ellison, the City of Little Rock has dedicated this public bench to Ellison. (Photo: Flint Taylor)

Alongside the large monetary settlement won by the family of police violence victim Eugene Ellison, the City of Little Rock has dedicated this public bench to Ellison. (Photo: Flint Taylor)

In June, Little Rock City Manager Bruce Moore sent the city’s written apology to the Ellison family. Citing the often quoted Chapter 3 of the Book of Ecclesiastes, the City Manager wrote that it was time to “build, to mend, and to heal.” Quoting Mark 3:25 in saying that “a house divided against itself cannot stand,” Moore continued that “a fragmented Police Department and Little Rock citizenry only serves as a detriment to our shared goal of helping Little Rock grow and prosper.” While the letter did not admit that the officers, who, unfortunately are still on the force, acted wrongfully, it did offer an apology:

In order to begin the healing process for the family, the Little Rock Police Department and the City of Little Rock, on behalf of the City, I want to extend a sincere apology for the death of your father. While we have all vigorously debated the events that led to his death, the time for healing has begun.

On November 4, a beautiful sunny morning in Little Rock, a group of about 125 family members, ministers and activists from Little Rock’s African American community, the Ellison family lawyers, other supporters and the local media gathered in scenic MacArthur Park in downtown Little Rock to dedicate the memorial bench. Moore gave the opening remarks, followed by an opening prayer by the Rev. Dr. C.E. McAdoo of St. Andrew United Methodist Church. After a musical interlude and an inspirational poem, the Ellison brothers spoke.

Spencer spoke first, saying that it was “with immense honor that I stand before you today to memorialize this bench in dedication to my father,” who was “a man of faith, integrity and principle.” He described his father as a “proud Navy veteran who served his country during the Vietnam Era” and “treated people the way he wanted to be treated.” He was “a great artist who drew and painted, expressing his love of life through his artistic abilities.” Saying that his father’s tragic death still haunts him, he said he found “some peace in knowing that even though this fight isn’t over, change will soon come.” In a promise to his father, he said “my father’s legacy of living a principled, respectful life lives on in his sons.”

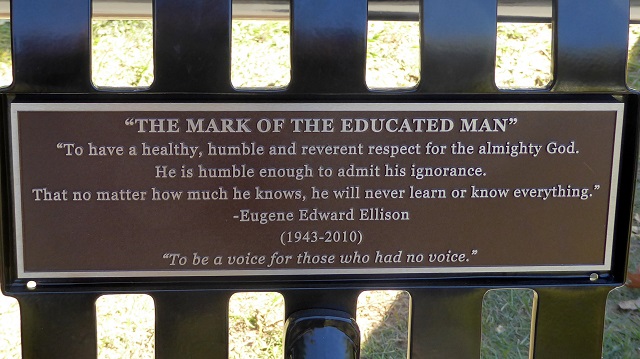

The memorial bench that was dedicated to police violence victim Eugene Ellison on November 4, 2016, bears this inscription in his memory. (Photo: Flint Taylor)

The memorial bench that was dedicated to police violence victim Eugene Ellison on November 4, 2016, bears this inscription in his memory. (Photo: Flint Taylor)

Spencer continued by speaking about how the bench should inspire us all:

I want you to read his passionate inscription on the bench and know that Mr. Eugene Edward Ellison stood for justice…. And while you are sitting on the bench I want you to know that, “Nothing will work, unless you do.” I want you to sit on this bench and know that “the best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service of others.” I want you to sit on this bench and know, “If you don’t stand for something you’ll fall for anything.”

Troy Ellison — who has had to be more circumspect because of his continuing role as a Little Rock police lieutenant — followed his brother to the podium. He acknowledged his relatives, thanked his brother for spearheading the public campaign for justice, and thanked Moore for the “unique gesture that no other city has dared to duplicate or achieve.” Troy then captured the scenic peacefulness of the bench’s placement by telling a personal story:

In search of a location for the bench, I stumbled upon a homeless man sitting on the bench previously positioned there. I was in uniform, and the man immediately started looking for his identification and explaining why he could not find it. I told him not to worry about it. When I began to tell him the reason why I was here, he completely ignored me and appeared to start daydreaming. I knew then this was an ideal place for the bench. When sitting here, you can put your mind in a place where no one (not even a policeman) can interrupt your peace.

He then issued a call to action to those in attendance:

This memorial will be remembered as another step toward healing for my family. Together, we can take the first step toward bringing our community together, to work toward bridging the gap of understanding and disconnect between law enforcement and our community. The time for talk must end. Everyone in attendance this morning has taken that first step. By your presence, you have now positioned yourself to being a part of a movement of positivity and not allowing negativity to sustain that imaginary barrier. I define this moment as a movement to recognize our issues and address them with action and not just discussion.

Troy finished with a personal pledge to continue taking part in the movement against police violence, even as he serves as a police lieutenant himself. “This ceremony marks the beginning of my official pledge of dedication to being a part of the movement, not because of, but in spite of,” he said. “I have forgiven these officers for their actions and I pray for strength to continue to move forward and commit to answering the call to action.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.