Activists marauding Google buses, the hippie enclave turning into a playground for the rich, the threat of beautiful Victorians being plowed over for boxy condos. The housing crisis in San Francisco is capturing the world’s attention, and it seems like every day there’s someone putting forward the magic bullet to mow down the housing boogeyman. But many of these solutions are obsessively focused on saving the day with a build, build, build strategy.

Affordability for working-class people in San Francisco isn’t going to come from letting profit-driven developers have their way. After months of research and interviews by a journalist who has worked as a developer and on housing policy, this feature dismantles the arguments driving housing policy in the city and offers real solutions instead of “trickle-down” approaches.

San Francisco is the epicenter of the changing US economy. The gap between rich and poor in the United States is growing as the middle class and manufacturing sector are being squeezed out. A recent study equated San Francisco’s income gap with Rwanda’s. City living is ideal for young professionals and, increasingly, the suburban elite. US cities need to look at smarter ways to thrive and not simply rely on the invisible hand to provide housing for working-class Americans.

“It’s a complicated issue and you just can’t quote Adam Smith in your Economics 101 textbook to say that’s going to solve the problem,” said Doug Engmann, a venture capitalist and original member of the Pacific Stock Exchange. He’s referring to laws of supply and demand, which dictate that price equilibrium will be reached when quantity demanded by consumers matches the quantity produced by suppliers. “You have to understand how they work in special situations and you have to look at the situation that we’re in,” Engmann said during an interview in his financial district office.

This feature debunks supply-side arguments myth by myth and gives recommendations for solutions. Upzoning won’t solve the housing crisis. Luxury demand by techies is the most dominant factor driving up prices. No matter how low building costs dip or how streamlined the process becomes, as long as that luxury demand dominates, developers won’t prioritize the housing needs of working-class people.

Myth 1: Housing is expensive because there isn’t enough supply.

Fact: Housing is expensive because so many techies and investors want to rent and buy in San Francisco. Prices are mostly determined by high-end demand.

Tech workers lined up for their shuttles to work. (Photo: Joseph Smooke)

Tech workers lined up for their shuttles to work. (Photo: Joseph Smooke)

There is intense competition within technology companies for the “best and brightest” that is creating a huge concentration of workers with high salaries on the San Francisco Peninsula. Many of these tech workers are vying for housing in San Francisco and developers are eager to cash in.

The San Francisco Peninsula, which reaches from the city to San Jose and encompasses Silicon Valley, is the epicenter of US tech. It’s anchored by the two most valuable firms in the world, Apple and Google,with their headquarters in Silicon Valley. Within the city, Salesforce is San Francisco’s biggest tech employer and growing. They recently inked a deal to lease 30 floors in the Transbay Tower, which will be the tallest office building west of Chicago. These massive tech firms need highly skilled and educated technicians to maintain their competitive edge.

The average tech worker in San Francisco makes a whopping salary of more than $156,000 per year and the average Silicon Valley tech worker makes nearly $200,000 per year.There are 300,000 plus (added numbers from p. 60-64) tech workers in companies on the San Francisco Peninsula. This means there are a huge number of people, roughly equal to three-quarters of the entire population of Oakland, making a tremendous amount of money in the Bay Area, and many are young professionals looking to live in San Francisco. Meanwhile, 50 percent of San Francisco households are living on less than $74,000 per year and over 110,000 San Franciscans live below the poverty line.

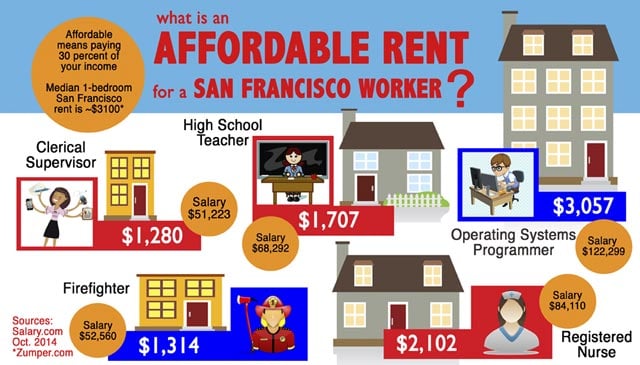

What is an affordable rent for a San Francisco worker? (Photo: Dyan Ruiz)

What is an affordable rent for a San Francisco worker? (Photo: Dyan Ruiz)

Landlords of existing properties and developers of new housing will charge as much as they can. With so many people around making six-figure salaries, they can charge a lot. San Francisco is the most expensive US city for rent with median rent for a one bedroom around $3,100 per month. Average rents in San Francisco are out of reach for most, but not for the average techie. Going by the federal affordability standard, it’s actually affordable for someone making $156,000 a year to pay up to $3,900 per month in rent. People with high salaries can pay an even bigger chunk of their pay for housing and still have plenty left over, thus the intense competition for housing, which keeps prices skyrocketing.

In his paper, “Why you can’t afford a house in San Francisco,” financial theorist William Bernstein says that where there is a large concentration of wealthy people, housing prices will be high. Most people “mortgage themselves to the hilt” he says, so rich people can and will spend more for a house. Add to that many others with the same good fortune, and so it goes that the higher the average salary in a city, the higher the average cost of a house.

“You can think of a house in San Francisco the same way you might think of a Jackson Pollack or a Vermeer or a de Kooning. It’s a very desirable item being chased after by very wealthy people,” Bernstein said in an interview via Skype.

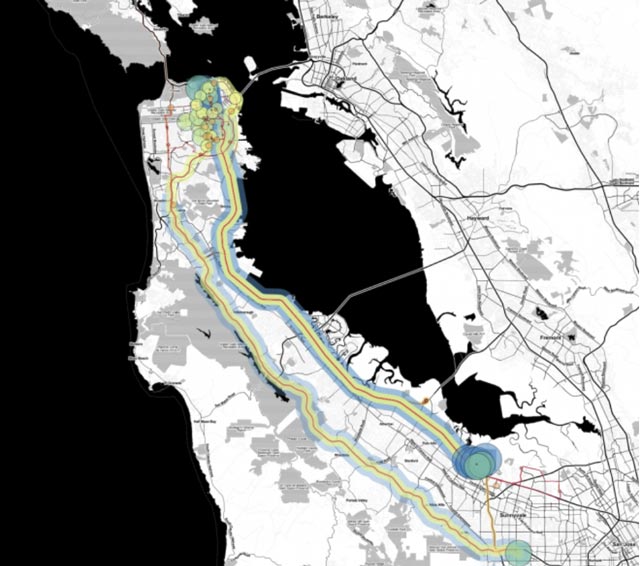

Map of tech shuttle routes between San Francisco and Silicon Valley. (Photo: Wired.com | “Mapping Silicon Valley’s Gentrification Problem Through Corporate Shuttle Routes”)

Map of tech shuttle routes between San Francisco and Silicon Valley. (Photo: Wired.com | “Mapping Silicon Valley’s Gentrification Problem Through Corporate Shuttle Routes”)

The average techie can easily pay for an apartment that current tenants who are teachers, government workers, nurses or baristas can’t afford. This is driving evictions way up. Tech jobs also come with perks like the emblematic tech buses transporting employees in private luxury from their homes in hip, exciting San Francisco to their offices in suburban Silicon Valley.

Consider that the same phenomenon is happening right now in Manhattan, but in reverse. Despite a chronically limited supply of housing, and an increasing population, Manhattan rents are down apparently because the average salary is down, reports The New York Times.

One can’t blame the insatiable demand for housing in San Francisco soley on techies. It’s also from high-paid executives and managers in other sectors, and from foreign investors. The Chinese real estate market is soft, leading many Chinese investors to buy housing in the United States. A recent investigation found that nearly 40 percent of condos have absentee owners from around the United States, including Silicon Valley.

This is not an indictment of tech workers, the tech industry, foreign investors or even developers. It’s an acknowledgement of the macro-economic forces driving the housing prices in one of the world’s most desirable cities.

Take it from a person who knows supply and demand very well, the president of the San Francisco-based start-up and real estate investment firm, Engmann Options Inc. “You can’t build enough housing units to meet that insatiable demand in order to get the price down where it can become more affordable,” Engmann said.

“The fact that more market rate housing is built is not going to impact the demand at the lower income levels,” Engmann said. “The trickle down effect doesn’t work because all that housing will be taken up by people who can afford it higher.”

Myth 2: Developers are building high-end housing because it’s expensive to build housing in San Francisco.

Fact: Even if building costs are lower, developers will build expensive housing, as long as there’s enough demand for it.

Man at rally against market rate housing in the Mission District, San Francisco. (Photo: Joseph Smooke)

Man at rally against market rate housing in the Mission District, San Francisco. (Photo: Joseph Smooke)

People argue that the cost of building in San Francisco, with all of its activists, environmental regulations, union labor and permitting hurdles, is making it so developers can only build luxury housing. If building costs were lower and the approval process was streamlined, developers would provide housing that working-class people could afford. But this reasoning assumes developers are going to pass on the savings. With so much demand at the high end of the market, they’re just not going to.

Think about it from the perspective of a developer. The developer starts with figuring out how much they can charge the renters or buyers who are going to live there. All the development costs are just considerations when deciding if the project is worthwhile. Will the developer be able to make enough money at the end of the day after suffering all these costs? The reason so much development is happening in San Francisco is that the answer is “Yes!”

Despite all the costs that make building a unit in San Francisco cost more than $400,000, there is so much high-end demand that developers still make plenty of money at the end of the day. San Francisco’s housing pipeline, the amount of housing projected to be built (p. 13) in the city, currently stands at 50,000 units. This will increase the city’s housing stock by roughly 15 percent, although it will take a number of years for these homes to be move-in ready. Expensive or not, it’s still financially worthwhile to develop in San Francisco.

If building costs were lower and incomes stayed high, developers would just make more profit. They’re not going to charge less so that working-class people can be housed while they can charge the clamoring masses of rich people more.

Myth 3: Let developers build taller buildings. Then prices will go down.

Fact: Upzoning won’t solve the housing problem for many reasons.

View of Bernal Hill from Noe Valley, San Francisco. (Photo: Joseph Smooke)

View of Bernal Hill from Noe Valley, San Francisco. (Photo: Joseph Smooke)

San Francisco is a small city, just 47 square miles with only 13 square miles available for housing. Therefore, the only way to add a lot more housing is to build up. But changing building regulations to allow taller buildings isn’t going to make costs go down.

The first reason is that if you upzone a piece of land, the value of that land will increase. A textbook way to appraise land value is the Income Approach Method. This evaluates the potential income that could be generated from developing that land. If the same lot is rezoned to allow more units, this means greater potential income. Greater potential income increases land value. Costs increase as developers will have to pay more to buy the upzoned land.

The second reason upzoning won’t make prices fall is that building costs go up the more stories are added. Physics and building codes make it so that as buildings get taller, they go from wood construction (the cheapest), to concrete (more expensive), to steel (most expensive), said contractor Robert Carpenter in an email. So units in high-rise buildings aren’t really cheaper to build.

As the cost of building increases, that will only incentivize developers to charge more to the eventual buyers and renters in order to protect their profit. “In areas that are zoned for high rises, there’s no way that an affordable housing developer . . . can compete with the luxury buildings,” said co-director of the Council of Community Housing Organizations in San Francisco, Fernando Martí, in an interview at his office.

Thirdly, upzoning won’t significantly increase the supply of housing – at least not for a while. Most of San Francisco’s land is already developed. If you increased the zoning on land that already has buildings on it, the property’s owner needs a financial incentive to tear down what’s there. Because of this barrier, past efforts have proven to be futile.

For example, starting in 2008, the San Francisco Planning Department and housing advocates tried to work with Safeway and other supermarket owners to demolish their buildings and parking lots to rebuild with housing on top. But the owners stood to lose all their income during construction. In order to make it worthwhile, there has to be a lot of money to be made once everything was rebuilt – which doesn’t leave any incentive for rebuilding with low-cost housing, especially with the demand for luxury housing so high.

The classic case study against adding density to make housing affordable is Manhattan. There are nearly 70,000 people per square mile living in Manhattan. The median value of owner occupied units is $827,300 and average rent is about $3,800 per month. As in many other desirable cities, density is not making things affordable.

It’s not as if San Francisco is balking at building up. San Francisco is in the top 10 of US cities building above their historical norm (36 percent higher), and 84 percent of those new developments are multi-unit. New York is number two on that list, building 70 percent above its norm; 92 percent are multi-unit. Both cities are dense and still expensive.

Myth 4: As long as you can upzone and deregulate, you can build and build to the point where prices will go down.

Fact: That’s not the way that housing development works. Housing finance has limits.

Financial District, San Francisco. (Photo: Joseph Smooke)

Financial District, San Francisco. (Photo: Joseph Smooke)

Even if residents and city politicians agree on how to make housing development easier and denser, that’s not going to change how banks and housing finance work. Developers won’t be able to build an unlimited supply of housing, or even build to a point where prices will drop substantially.

Say San Francisco pushed to flood the housing market with over 100,000 units in just a few short years in an attempt to lower prices. At that point when prices start declining, external pressures are going to kick in. Interest rates might rise to cool the market, making it more expensive for developers to finance new construction. Banks will also stop lending because they don’t want to invest in a sinking market. Investor capital will stop flowing because investors won’t be able to forecast a sufficient profit and will seek investments with higher returns. So, the production of housing will slow or stop before prices start to drop too much.

Similarly, a developer has limits when housing prices are falling. Development is a risky business even in good times. It takes a housing development three to five years or sometimes longer to get from start to finish – through feasibility, design and permitting, construction, then finally occupancy. All of the money invested in the development depends on forecasts of what people might be willing to pay for the apartments or condos when they’re move-in ready. If there’s any sign of a declining market, developers may still buy sites, but they’ll sit on them until prices start going up again. So whether it’s the banks, investors or developers getting cold feet, increasing supply isn’t going to drop prices to a level working-class people can afford.

“If let’s just say the tech economy slows down and people’s incomes aren’t going up and they’re not getting big stock options,” Engmann said, “they may be thinking, ‘Well, for this unit, I’m not going to pay $4,000. For this unit, I’ll pay $3,500.’ But it’s not going to go down to $1,500. It’s not going to happen.”

Why? That developer still has to pay the bank back their loans based on the forecast from years ago. The developer thought they could charge $4,000 per month for rents. Now that’s not going to happen, so they’ll drop the rents to $3,500. They’ll have less profit, but they can still pay the bank back. If the market takes a real dive, the developer’s not going to drop the rents to $1,500, or anywhere near the level that a working-class family can afford.

As in the foreclosure crisis when people lost their homes because they couldn’t pay back their loans, banks aren’t going to let developers pay them back less just because the market tanked and there’s no more demand for $4,000 per month apartments. US housing works on a for-profit model. Building doesn’t happen if developers are forecasting they’re going to lose money.

Solutions: Rethinking Private and Public Sector Roles in a New Economy

San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee proposed in January 2014 that the city build 30,000 units by 2020, with at least a third being affordable to people earning up to 120 percent (p.16) of area median income, which is $116,500 for a family of four. But remember from fourth grade math class what median means – half below and half above. The city should be building at least half of the units to be affordable up to 100 percent of median income. Not a third up to 120 percent, otherwise a majority of the housing built will be unaffordable for most people.

Furthermore, this level of affordable housing falls short of addressing price escalation, despite Lee’s claims. City & County chief economist Ted Egan says building 100,000 new housing units will only make a quarter of the housing market affordable to some middle-income people. So 30,000 units aren’t going to bring prices down to the level working-class people can afford.

So far this has been a lot of what doesn’t work. Here are some creative ideas, presented briefly, for what could work to build housing for working-class people in San Francisco. Keep in mind that since the Reagan administration of the 1980s, federal housing subsidies for the poor and working class have been cut year after year (p. 6). State subsidies have also been cut. This leaves San Francisco pretty much on its own when it comes to meeting its affordable housing shortage.

San Francisco Should:

Protect existing tenants by

- Preserving existing affordable housing: The city needs to continue to work with state legislators to restrict the use of the Ellis Act for landlords who have owned the property for less than five years to discourage “flipping.”

- Extending just cause eviction protections: The city should revive legislation vetoed in 2009 that would extend just cause eviction protections to tenants not covered by rent control.

- Prioritizing maintenance of existing affordable housing: The city should maintain existing nonprofit (affordable) and public housing with an annual budget commitment. These efforts should not be counted toward goals for producing new units of affordable housing (p. 14).

Build new affordable housing by

- Aggressively buying land: The city should buy as many developable sites as possible to reserve them for affordable housing. Land around transit hubs and other strategic locations should be rezoned for affordable housing.

- Capturing vacant units for affordable housing: There are approximately 35,000 vacant units (p. 58) that should be prioritized for the existing Small Site Acquisition Program. Take the units by eminent domain for the public good and tie this to Section 8 tenants.

- Expanding the Small Sites Acquisition Program: The city should invest more money in the program, expand it to properties of two to 25 units including retail at the ground level, and they should become placement sites for Section 8 households.

- Updating the Jobs Housing Linkage Program: This city program can generate more revenue for affordable housing if it includes a higher rate for tech companies because of the way they use space. Also include companies with an aggregate of 25,000+ square feet throughout the city.

- Creating a Workforce Housing Equity Fund: Tech companies taking advantage of tax breaks should pay into a Workforce Housing Equity Fund for building affordable housing as part of their Community Benefits Agreements.

- Creating a model Inclusionary Housing Program: Developers could opt into a program designed in such a way that half of the units are affordable to the average median income, which would make them eligible for 80/20 financing, including exempt bond financing and equity from the Federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit program. This reduces their financing costs and risks.

- Allocating more hotel tax revenue to affordable housing: New tax revenue from short-term rentals such as AirBnB should go to affordable housing for all households.

- Implementing a Housing Balance policy: A Housing Balance ordinance could ensure that at least half of all new housing is affordable before allowing market rate housing.

- Passing an Affordable Housing Bond: The city needs to raise a lot more money than the Affordable Housing Trust Fund of 2012 can provide. There needs to be an Affordable Housing Bond in 2015 in order to fund affordable housing development.

Initiate state and regional strategies by

- Negotiating a partnership with the state: Rather than waiting for a new statewide affordable housing funding program to be created, we should work with the governor and legislature to create a funding program that leverages San Francisco’s city budget investment.

- Developing mixed income housing in West Oakland: A natural type of project for state leveraging, San Francisco could partner with the City of Oakland to develop mixed income housing with retail and community services on unused and vacant land in West Oakland, one BART stop away from downtown San Francisco.

We have a new economy in San Francisco, the kind of economy that other cities envy. It’s dynamic, innovative, wealthy and prestigious. This economy generates new challenges. All eyes are on us to see how we will solve these challenges.

We have 10 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.