Part of the Series

Progressive Picks

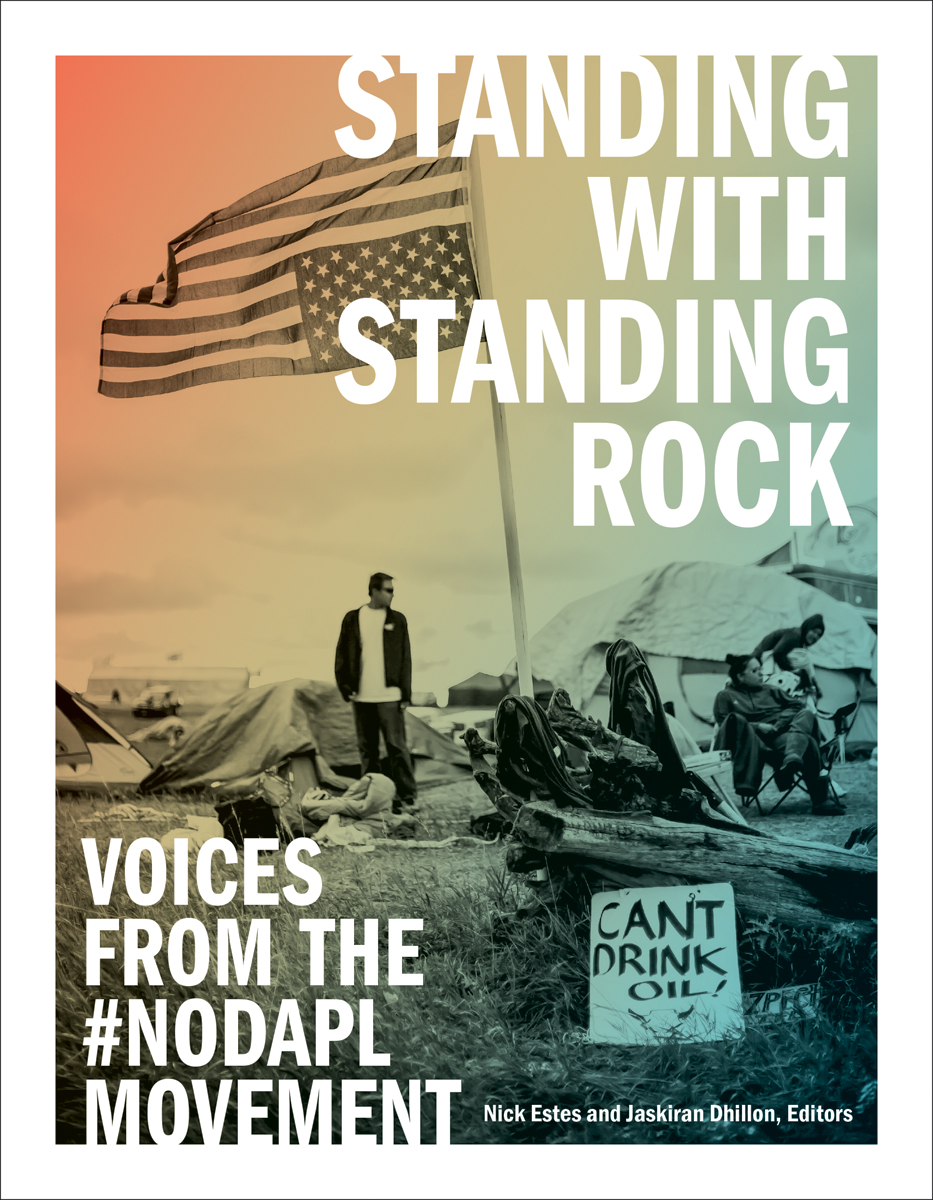

“Colonialism, imperialism, and racial capitalism are impacting people across the globe, both historically and in the contemporary moment,” write Nick Estes and Jaskiran Dhillon, editors of Standing With Standing Rock: Voices From the #NoDAPL Movement. In this interview, Estes and Dhillon discuss how this collection situates the #NoDAPL movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline within a broader historical context — a context that transcends the Oceti Sakowin-led movement and emphasizes Indigenous sovereignty and decolonization as central to successfully resisting extractivism.

Samantha Borek: Standing with Standing Rock: Voices from the #NoDAPL Movement is an extensive collection of essays, strategies, reflections, interviews and even poetry from the movement. How does this curation of work function now almost three years after the removal of the Oceti Sakowin camps?

Nick Estes and Jaskiran Dhillon: The perspectives offered within Standing with Standing Rock show that the movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline didn’t necessarily begin at Standing Rock in April 2016, with the creation of Sacred Stone Camp, nor did resistance technically end in February 2017, with the eviction of Oceti Sakowin and Sacred Stone camps. Almost three years later, this collection functions as a critical historical archive of movement voices while also situating it within a long historical arc. It also offers a deep contextualization on the social, cultural and spiritual significance of the #NoDAPL movement from a distinct viewpoint of Oceti Sakowin writers, scholars and knowledge-keepers. The centrality of Indigenous knowledge and necessity for decolonization continue to be glossed over in mainstream climate movements. In that sense, this volume exceeds the category of what is typically seen as just a “local culture” or just an “Indian problem.” Within these pages, thinkers, organizers, and Water Protectors also connect Black and Palestinian liberation with Indigenous struggles across time and space. Standing Rock was, after all, one uprising among a constellation of ongoing Indigenous uprisings, such as at Unist’ot’en Camp and Mauna Kea.

It’s also important to remember, as the contributors to this volume demonstrate, the Indigenous-led movement against the Keystone XL Pipeline (KXL) dovetailed into the movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). President Obama’s denial for the construction of KXL’s northern leg in 2015 wasn’t the nail in the coffin for oil pipeline construction or Indigenous movements. Obama’s refusal to halt DAPL at the end of his term, and an overall ambivalence toward the expansion of carbon infrastructure, dovetailed into President Trump’s fast-track approval of KXL and DAPL. #NoDAPL happened during a pivotal presidential election year. The final leg of KXL is slotted for construction in 2020, trespassing through the heart of Oceti Sakowin territory and again during another round of U.S. presidential elections.

The visions of Water Protectors and the Oceti Sakowin, however, demonstrate a more radical and just alternative than what is currently on offer from settler governments. This book, which is not the final word on #NoDAPL and Indigenous resistance, will be key to thinking about Indigenous-centered climate justice as resistance grows.

In what ways did the Oceti Sakowin camps foster solidarity across many lines, especially with youth?

As is clearly outlined in various pieces throughout Standing with Standing Rock, solidarity across multiple lines of struggle was both key to the resistance against DAPL and builds on a long history of internationalism and comradery that transcends imposed colonial borders. Colonialism, imperialism and racial capitalism are impacting people across the globe, both historically and in the contemporary moment, and that requires building social movements that speak to one another and through which intersectional forms of oppression can be challenged, resisted and ultimately overthrown.

Organizers committed to Black and Palestinian liberation showed up at Standing Rock because they know that collective resistance is essential for global, revolutionary social transformation — it is important, of course, to be attentive to the distinctiveness of different struggles but is crucial for people to join forces. As we state in the introductory pages of the collection, “These are battles that require us to stand together, to find ways to build coalitions across variant political histories and contemporary life experience, and to remain unified against the colonial structures and forces that ultimately threaten the future of everything.” Indigenous young people readily stepped into this movement because they have the greatest and most immediate knowledge about what is at stake, which is life itself.

Mni Wiconi, or “Water is Life,” seems self-explanatory at first, but what does this really mean in the Indigenous perspective, and how is understanding it in this lens vital to any kind of movement work?

While “water is life” might seem like a generic phrase, the concept of Mni Wiconi is a Lakota and Dakota expression that is both esoteric and deeply grounded in history and place. For example, the Oak Lake Writers’ Society, which is comprised of Dakota, Nakota and Lakota writers, edited the volume This Stretch of the River (2006) to provide a counter-narrative to the U.S. commemoration of the bi-centennial of the Lewis and Clark expedition. For the Oceti Sakowin, the first European invaders came by water. In the 20th century, the United States and the Army Corps of Engineers used Mni Sose, the Missouri River, as a tool for dispossession. The Pick-Sloan dams flooded and destroyed Lakota and Dakota homelands, as well as other Missouri River Indigenous nations. In the 21st century, water again becomes a key resource for contestation during the North American oil boom. This long historical narrative — one that attempts to use Indigenous relations with the water and land against Indigenous peoples themselves — is key to understanding concepts such as Mni Wiconi.

The Oak Lake Writers’ Society members — such as Kim TallBear, Craig Howe, Edward Valandra, Nick Estes and Joel Waters — and other Lakota and Dakota writers and voices — such as Layli Long Soldier, Lewis Grassrope, LaDonna BraveBull Allard, David Archambault II, Mark K. Tilsen, and Marcella Gilbert — speak from a perspective grounded in relations to place that form the backbone of this anthology.

On one hand, access to clean drinking water is a fundamental human right. We can see how this right is denied according to race and class in places like Flint, Michigan. On the other hand, Indigenous relations to water and place are frequently mystified as ahistorical or over-romanticized. This volume attempts to place Mni Wiconi and the right to water within its proper historical, cultural and political context, a context that is grounded in Indigenous knowledge.

Indigenous sovereignty is pretty directly connected to environmental justice. Does the current wave of environmental movements (#FridaysForFuture, Extinction Rebellion, etc.) acknowledge that? Could they be centering Indigenous voices more?

One of the things that the resistance at Standing Rock made clear is that Indigenous sovereignty is essential for environmental justice. An accurate examination of the social and political causes of climate change and related forms of environmental harm demands that we take a close look at the history of genocide, land dispossession, and concerted destruction of Indigenous societies and cultural practices that accompanies the irreversible damage wrought by environmental destruction. The kind of racial capitalism that is anchored to colonialism and imperialism has only been made possible through Indigenous dispossession and the invention of colonial law that supports and upholds an economic and political system based on extractivism. Our strongest chance of restoring balance on the planet and respecting the interconnectedness of all things, human and other-than-human, is to fervently advocate for justice for Indigenous communities and return to them the power of governance. Indigenous peoples currently protect 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity, and they carry disproportionate labor and risk on the front lines of environmental struggle all across the world — we should be taking our direction from them.

The current waves of environmental movements still fall short in articulating this kind of critical analysis; even the most seemingly progressive configurations of environmental justice have yet to centralize Indigenous leadership and questions of sovereignty in their platforms (see, for example, the Green New Deal). This is also not a question of “giving voice,” but drawing on Indigenous history, politics and leadership as the starting point from which all discussions begin.

How are histories of Indigenous styles of governance and education important not just to understanding the successes of #NoDAPL, but also to other movement work?

Indigenous governance is specific to each nation and arises in different contexts depending on the territory. It should not be confused with a universal approach, or a one-size-fits-all application. We can take our cues from Dakota scholar and elder Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, who argues for an endogenous approach to Indigenous studies — that is, foregrounding nation-specific epistemologies first and foremost. In that sense, we can understand #NoDAPL as arising specifically from the Oceti Sakowin tradition of resistance, historical knowledge and relations. As this volume shows — and, in turn, so too does the #NoDAPL movement — while an Oceti Sakowin perspective is the starting point, decolonization is not an exclusively Oceti Sakowin or Indigenous project. In fact, it can draw from a long-standing Indigenous tradition of diplomacy and alliance-making, of turning those seen as different into allies, comrades and sometimes relatives. If there is a lesson that movements can learn, it is that decolonization begins from the territories now colonized by settler states and the nations who have first made relations with the land, air and water. It will look different from place to place. But decolonization begins with the very Earth itself.

We have 10 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.