The latest COVID-19 booster shot is now available to the public. But this time, access is a bit more challenging.

Sanho Tree, a drug policy expert in Washington, D.C., has found getting previous vaccine doses to be “very orderly,” but has made five attempts to get the vaccine. After making his first appointment at a CVS on the other side of the city, the closest place it was available, he waited for 45 minutes when the pharmacist came out, looking “overworked and ragged,” and apologetically told him there were no shots left. His following attempts were canceled via CVS’s automated text messaging system.

“It really sucked,” he said. “From a public health standpoint, it’s a disaster.”

While previous vaccine doses and boosters were purchased by the U.S. government and distributed in community health centers, doctors’ offices, and retail pharmacies, responsibility for the latest COVID-19 vaccine has shifted into the hands of private companies. This means that pharmaceutical giants Pfizer and Moderna, the primary COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers, are contracting with individual insurance companies to sell the vaccine and distribute the doses.

As a result of these supply issues, in the first weeks of the roll-out, patients have faced problems with receiving their doses in retail pharmacies, while public health departments have reported delays in supplies and a dearth of information. Some people have been charged erroneously when the shot is supposed to be free for privately and publicly insured patients, with programs to temporarily help cover most costs for uninsured ones, particularly for children. But there have been delays in delivery for the children’s dose formulation of the vaccine. And the 25-30 million Americans who do not have health insurance — disproportionately people of color and low-income people — may still be charged for administration of the vaccine.

According to Leslie Ray, a psychotherapist in San Diego, accessing the new vaccine was “remarkably different than what I had experienced previously.” For each of her previous COVID vaccine doses, she’d been able to simply walk into the local Rite Aid. This time, she had to go to Rite Aid three times before there was sufficient stock, even though both the government’s online vaccine finder and Rite Aid’s website suggested walk-in doses would be available. At the time, the online scheduler didn’t show any appointments until late in October.

Though Ray was able to get her vaccine on Sept. 25, nearly two weeks after the vaccine was approved, the experience left a bad taste in her mouth. “The government should still be arranging this,” she said.

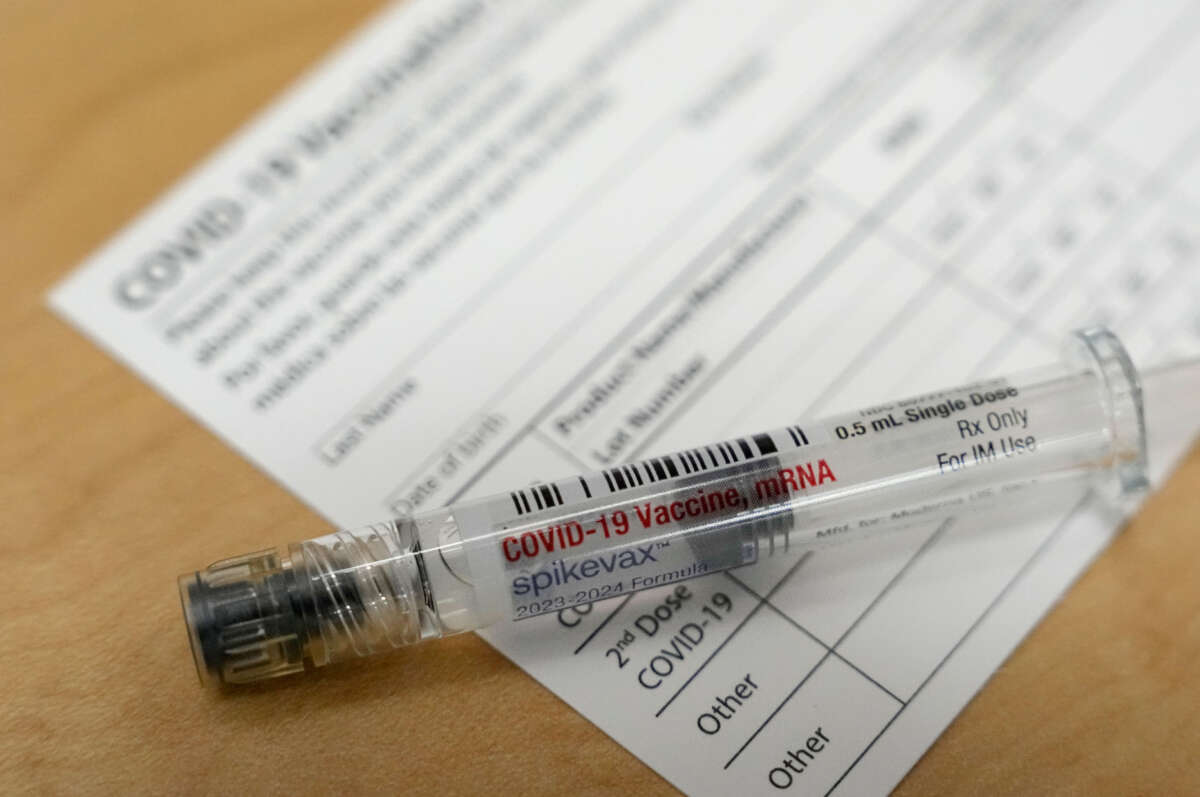

Andra Cernavskis, a law student in Oakland, California, also had an unsettling experience trying to get the new vaccine. She went to get her vaccine at a local Walgreens the first day it was available, on Sept. 18. But when she and other patients lined up for their dose, they received handouts about the vaccine that repeatedly referenced the “bivalent” dose, which was used to target last year’s Omicron’s strains. The customers were alarmed and concerned they would receive the wrong vaccine, Cernavskis explained.

“It got to the point where a few of us demanded to see the box that the vaccine had come in to properly clarify and confirm that it was indeed the new vaccine,” she said. “So they did end up bringing out the box and showed us it was the 2023-24 COVID shot.” The pharmacist didn’t have a good answer as to why the information on the shot for consumers hadn’t been updated yet.

Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra has since met with representatives from major insurance companies and retail pharmacies, promising that most hiccups have been cleared up and reaffirming that patients should not be charged for the shot. But patients are continuing to report problems, and the confusion and disorder of the rollout point to a lack of trust in the health care institutions and providers around COVID-19 — which could contribute to a lack of receptiveness to vaccination altogether.

The Biden administration has attempted to fill in the gaps in coverage to help get more people vaccinated free of charge. With few exceptions, all public and private insurers are required to make the shots no-cost. Uninsured children must also have guaranteed coverage through the Vaccines For Children program. Though they may still be charged an administration or office-visit fee, a “child cannot be refused a vaccination due to the parent’s or guardian’s inability to pay,” according to the CDC. The Biden administration’s attempt to pass a similar program for uninsured or underinsured adults failed to advance in Congress. However, free-of-charge vaccines will be temporarily available via HHS “Bridge Program” until funding runs out at the end of next year.

Complicated billing and tough contract measures designed by pharmaceutical and insurance companies to maximize profits will likely replicate health inequities that persist for uninsured people, lower-income adults, and people of color. These same groups have borne some of the worst health impacts of the pandemic.

“People of color are always at the bottom of that access to health,” said Cynthia Adinig, the co-founder of the BIPOC Equity Agency.

In the spring of 2023, KFF concluded that “disparities in the share that have received at least one COVID-19 vaccination dose have narrowed over time and reversed for Hispanic people. Despite this progress, a vaccination gap persists for Black people, and Black and Hispanic people are about half as likely as their white counterparts to have received an updated bivalent booster dose.”

Booster uptake rates are low across the board. While about 70% of Americans completed the primary series of vaccines, a paltry 17% reported getting bivalent boosters. Misinformation and confusion around waning immunity and inconsistent public messaging have led many to believe that they do not need additional doses, even though vaccine efficacy wanes over time. Others are simply “done” with COVID-19.

“I think as a society, people are intentionally putting themselves as far away from any COVID-speak as possible so they can live in their delusional wall that everything’s OK,” Adinig said.

Still, nearly half of U.S. adults said they will “definitely” or “probably” get the new vaccine, and a recent study showed that even a simple text message reminder could increase booster uptake by up to a third. But a rocky process and complicated pricing will certainly be a deterring factor.

While vaccination rates of children are lower than for adults, parents hoping to get the new vaccine for their kids have been stymied thus far. The children’s dose formulation has been even more difficult to access in retail pharmacies, with widespread delays and inconsistent availability. Because they’re now so much more expensive, many pediatricians’ offices have not stocked the new vaccine at all, and retail pharmacies don’t have it yet either.

Another point of concern is a lack of vaccine doses in high-risk settings like nursing homes, which affects both patients and their caregivers working in the facilities, and of any system of vaccination for people who are homebound.

However it appears public health and profit are at odds, and the government has found itself at the mercy of price-gouging by the pharmaceutical companies producing the vaccine. In 2021, Pfizer was accused of “bullying” governments in contracts to purchase the first round of vaccines, reportedly holding secretive negotiations with strict terms favorable to Pfizer, according to Public Citizen. The contracts the government watchdog was able to access “offer a rare glimpse into the power one pharmaceutical corporation has gained to silence governments, throttle supply, shift risk, and maximize profits in the worst public health crisis in a century.”

Since the first round of vaccines, Pfizer and Moderna have continued raising their prices. According to Stat News, the government paid $81.61 for the Moderna booster and $85.10 for the Pfizer shot this year, about three times as much as it paid for the 2022 round of boosters. Now, Pfizer and Moderna are charging private insurers $128 and $115 for Moderna and Pfizer, respectively.

Much of the public-facing brunt of these shifts will fall to pharmacists and pharmacy workers, who have been overworked and overburdened throughout the pandemic, especially during vaccine season. During last year’s bivalent vaccine rollout, a number of pharmacy workers reported being held to impossible metrics for numbers of vaccines administered at the cost of their other duties.

Taylor, a retail pharmacist in Arizona who is using a pseudonym for fear of retaliation at work, mentioned in an interview last year around the last major vaccine push that the “constant craziness increases the risk that mistakes will be made, or simply patients won’t be given the attention they deserve.”

Getting people up-to-date vaccines is particularly important given the recent surge in cases and hospitalizations, including continued outbreaks in schools, continued reports of long COVID, and other concerning post-viral conditions among children and young adults. Most if not all other measures for preventing the spread of COVID-19 have been abandoned, with masks no longer required even in health care settings and testing requirements dropped, so vaccination should be the bare minimum. Hearteningly, nearly 40% of adults report that they have started taking some precautions again with the latest surge, according to KFF, and the government recently announced another round of four free rapid COVID tests.

On Oct. 3, the FDA announced they had approved the Novavax vaccine for the latest coronavirus strain, which has been shown to be comparably effective in preventing serious cases of COVID as Moderna’s and Pfizers’. This will also help with supply issues once it becomes available in pharmacies.

But with huge swaths of the country and Republican lawmakers completely opposed to vaccination or any COVID-19 precautions or much needed funding, there are many barriers. And this polarization has only increased since the roll-out of the initial vaccine, according to Ashley Kirzinger, a director of survey methodology at KFF. As Kirzinger reported, nearly 4 in 10 adults who have previously gotten vaccinated say they won’t get this one.

But with the end of the public health emergency in May, most Americans are taking the lead of the government and no longer taking precautions or keeping up to date with COVID information. Ray, who learned about the new vaccine from Twitter, said that information is only readily available to those seeking it. “It feels like we’re on our own,” she said.

Prism is an independent and nonprofit newsroom led by journalists of color. We report from the ground up and at the intersections of injustice.

We have 9 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.