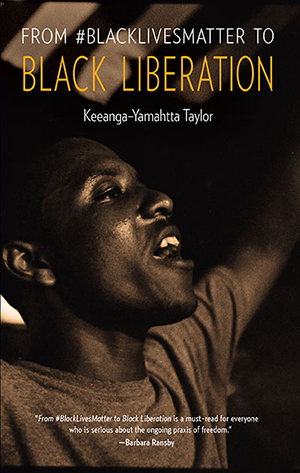

The following is an excerpt from From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation:

The murder of Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, in the winter of 2012 was a turning point. Like the murder of Emmett Till nearly fifty-seven years earlier, Martin’s death pierced the delusion that the United States was postracial. Till was the young boy who, on his summer vacation in Mississippi in 1955, was lynched by white men for an imagined racial transgression. Till’s murder showed the world the racist brutality pulsing in the heart of the “world’s greatest democracy.” To emphasize the point, his mother, Mamie, opted for an open-casket funeral to show the world how her son had been mutilated and murdered in the “land of the free.” Martin’s crime was walking home in a hoodie, talking on the phone and minding his own business. George Zimmerman, now a well-known menace but then portrayed as an aspiring security guard, racially profiled Martin, telling the 911 operator, “This guy looks like he’s up to no good, or he’s on drugs or something.” The “guy” was a seventeen-year-old boy walking home from a convenience store. Zimmerman followed the boy, confronted him, and eventually shot him in the chest, killing him shortly thereafter. When the police came, they accepted Zimmerman’s account. Martin was Black and the default assumption was that he was the aggressor – so they treated him as such. They tagged him as a “John Doe” and made no effort to find out if he lived in the neighborhood or was missing. But the story began to trickle through the news media and, as more details became public, it was clear that Martin had been the victim of an extrajudicial killing. Trayvon Martin had been lynched.

Within weeks, marches, demonstrations, and protests bubbled up across the country. The demand was simple: arrest George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin. The anger was fueled, in part at least, by the overwhelming double standard: if Martin had been white and Zimmerman Black, Zimmerman would have faced immediate arrest, if not worse. Instead, the case showed the deadly consequences of racial profiling and of the alternating fear and disgust of Black boys and men that allowed the police to try to sweep the matter under the rug. The protests were national, as they had been for Troy Davis, but they were much more widespread. This was the impact of Occupy, which had relegitimized street protests, occupations, and direct action in general. Many of the Occupy activists who had been dispersed by police repression the previous winter found a new home in the growing fight for justice for Martin. Protests in Florida and New York City reached into the thousands, with smaller protests in cities across the country.

The legal inaction around Martin’s murder on the local, state, and federal levels demonstrated the racist hysteria that prevailed throughout American society. Martin was not a suspect because he had actually done anything suspicious; he was just Black. For weeks, President Obama deflected questions, commenting only that it was a local case. It took more than a month for Obama to finally speak publicly about the case, famously saying, “If I had a son, he’d look like Trayvon. . . When I think about this boy, I think about my own kids.” But he also said, “I think every parent in America should be able to understand why it is absolutely imperative that we investigate every aspect of this, and that everybody pulls together – federal, state and local – to figure out exactly how this tragedy happened.”

(Image: Haymarket Books)Obama could not come out and say the obvious, but the fact that he spoke at all was evidence of the growing momentum of the street protests that had been building for weeks. Martin’s murder was a national and international embarrassment. Black people may have understood that Obama could not lead a social movement against police brutality as the president, but how could he not use his seat to amplify Black pain and anger? Though everyone applauded his personal touch, Obama was signaling that the federal government would stay out of the “local” matter. But it was exactly for moments like these that Black people had put Obama in the White House. “We had hope riding – we got Barack Obama elected and got him reelected, but this is still happening. That’s kind of like saying, you knew the system hated you, and now, whatever speculation you had about it, even though Barack’s in office, you have to check yourself,” said poet Frankiem Nicoli.

(Image: Haymarket Books)Obama could not come out and say the obvious, but the fact that he spoke at all was evidence of the growing momentum of the street protests that had been building for weeks. Martin’s murder was a national and international embarrassment. Black people may have understood that Obama could not lead a social movement against police brutality as the president, but how could he not use his seat to amplify Black pain and anger? Though everyone applauded his personal touch, Obama was signaling that the federal government would stay out of the “local” matter. But it was exactly for moments like these that Black people had put Obama in the White House. “We had hope riding – we got Barack Obama elected and got him reelected, but this is still happening. That’s kind of like saying, you knew the system hated you, and now, whatever speculation you had about it, even though Barack’s in office, you have to check yourself,” said poet Frankiem Nicoli.

It is impossible to know or predict when a particular moment is transformed into a movement. Forty-five days after George Zimmerman murdered Trayvon Martin in cold blood, he was finally arrested. It was the outcome of weeks of protests, marches, and demonstrations, many of which had been organized through social media, beyond the conservatizing control of establishment civil rights organizations. Parents, families, and friends of others killed by police, like Alan Blueford, Ramarley Graham, James Rivera, Danroy “DJ” Henry, and Rekia Boyd, fought alongside local activists to bring attention to the murders of their children and loved ones.

I wrote that summer of the gathering tension over unpunished killings by police:

If the police continue to kill Black men and women with impunity, the kind of urban rebellions that shook American society in the 1960s are a distinct possibility. This isn’t the 1960s, but the 21st century – and with a Black president and a Black attorney general serving in Washington, people surely expect more. Meanwhile, in a matter of a few days in late July, near-riots broke out in Southern California and Dallas after police, growing more brazen in their disregard for Black and brown life, executed young men in broad daylight, out in the open for all to see. . . There’s a growing feeling of being fed up with the vicious racism and brutality of cops across the country and the pervasive silence that shrouds it – and people are beginning to rise against it.

In the summer of 2013, more than a year after his arrest, George Zimmerman was found not guilty of the murder of Trayvon Martin. His exoneration crystallized the burden of Black people: even in death, Martin would be vilified as a “thug” and an aggressor, Zimmerman portrayed as his victim. The judge even instructed both parties that the phrase “racial profiling” could not be mentioned in the courtroom, let alone used to explain why Zimmerman had targeted Martin.

President Obama addressed the nation, saying, “I know this case has elicited strong passions. And in the wake of the verdict, I know those passions may be running even higher. But we are a nation of laws, and a jury has spoken. We should ask ourselves, as individuals and as a society, how we can prevent future tragedies like this. As citizens, that’s a job for all of us.” What does it mean to be a “nation of laws” when the law is applied inequitably? There is a dual system of criminal justice – one for African Americans and one for whites. The result is the discriminatory disparities in punishment that run throughout all aspects of American jurisprudence. George Zimmerman benefited from this dual system: he was allowed to walk free for weeks before protests pressured officials into arresting him. He was not subjected to drug tests, though Trayvon Martin’s dead body had been. This double standard undermined public proclamations that the United States is a nation built around the rule of law. Obama’s call for quiet, individual soul-searching was a way of saying that he had no answers.

For Generation O, this response illustrated the limits of Black political power. FM Supreme, a young Black hip-hop and spoken-word artist from Chicago, described the meaning of Zimmerman’s exoneration:

When they announced it, it felt like a movie. . . I just was like, man, this is fucked up. Are you kidding me? I wasn’t really surprised, but I wasn’t prepared for that. Overall, the decision that was made reinforces that the United States of America has no value for the life of Black people. . . How they demonized Trayvon Martin, how they were prodding his dead body to see if he had drugs in his system – they don’t value us. They didn’t check to see if George Zimmerman had drugs in his system. . . We gotta move. We’ve got to take action. Specifically, we’ve got to holler at Stand Your Ground. We need to address racism in America. We need to hit them economically. And so we have to come up with a strategy. We need to recall Emmett Till and how after his death, there was Rosa Parks and the bus boycotts.

Almost two years after Zimmerman was acquitted, the DOJ quietly announced it would file no federal charges against him. Martin’s mother, Sybrina Fulton, said, “What we want is accountability, we want somebody to be arrested, we want somebody to go to jail, of course.”

The acquittal did not spell the end of the movement; it showed all the reasons it needed to grow. Out of despair over the verdict, community organizer Alicia Garza posted a simple hashtag on Facebook: “#blacklivesmatter.” It was a powerful rejoinder that spoke directly to the dehumanization and criminalization that made Martin seem suspicious in the first place and allowed the police to make no effort to find out to whom this boy belonged. It was a response to the oppression, inequality, and discrimination that devalue Black life every day. It was everything, in three simple words. Garza would go on, with fellow activists Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi, to transform the slogan into an organization with the same name: #BlackLivesMatter. In a widely read essay on the meaning of the slogan and the hopes for their new organization, Garza described #BlackLivesMatter as “an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise. It is an affirmation of Black folks’ contributions to this society, our humanity, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression.”

Zimmerman’s acquittal also inspired the formation of the important Black Youth Project 100 (BYP 100), centered in Chicago. Charlene Carruthers, its national coordinator, said of the verdict, “I don’t believe the pain was a result, necessarily, of shock because Zimmerman was found not guilty . . . but of yet another example . . . of an injustice being validated by the state – something that black people were used to.” In Florida, the scene of the crime, Umi Selah (formerly known as Phillip Agnew) and friends formed the Dream Defenders; for thirty-one days they occupied the office of Florida governor Rick Scott in protest of the verdict. Selah said, “I saw George Zimmerman celebrating, and I remember just feeling a huge, huge, huge . . . collapse. . . . I’ll never forget that moment . . . because we didn’t even expect that verdict to come down that night, and definitely didn’t expect for it to be not guilty.” Selah quit his job as a pharmaceutical salesman to organize full time.

No one knew who would be the next Trayvon, but the increasing use of smartphone recording devices and social media seemed to quicken the pace at which incidents of police brutality became public. These tools being in the hands of ordinary citizens meant that families of victims were no longer dependent on the mainstream media’s interest: they could take their case straight to the public. Meanwhile, the formation of organizations dedicated to fighting racism through mass mobilizations, street demonstrations, and other direct actions was evidence of a newly developing Black left that could vie for leadership against more established – and more tactically and politically conservative – forces. The Black political establishment, led by President Barack Obama, had shown over and over again that it was not capable of the most basic task: keeping Black children alive. The young people would have to do it themselves.

Copyright (2016) by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor. Not to be repubished without permission of Haymarket Books.

Full footnotes can be found within the book, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation.

In Chicago? Catch Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor in conversation with activist and scholar Barbara Ransby on Wednesday, April 6. The event will begin at 7 pm in the Chicago Cultural Center’s Preston Bradley Hall. Tickets are free and can be reserved in advance via Eventbrite.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.