In the wake of the most backward-looking presidential campaign in modern US history, it is now clear that we live in what the late sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman described as a “retrotopia,” a society in which fear of the future has caused mass nostalgia for a past that never existed. The current retrotopian movement is a reaction to an institutional politics, on both the left and right, that for nearly four decades has posited the future as an inevitable continuation of globalized neoliberal capitalism.

In spite of being packaged in the guise of 24/7 wired modernity, this vision of the future is horrifying to voters because it is a formulation in which they do not matter. Tayyab Mahmud, director of the Center for Global Justice at Seattle University School of Law, notes that as the “iron hand of the state works in concert with the hidden hand of the market” to maximize profits worldwide, people increasingly feel like pawns at the mercy of deeply impersonal global forces over which they have no control. Nearly 1 billion people, Mahmud reports, are already considered to be a form of “surplus humanity” for whom modern capitalism has no use. Even for those who might not feel immediately threatened, incessant resource wars, the seemingly ubiquitous threat of terrorism and apocalyptic environmental degradation create a sense of subliminal dread about the future.

Donald Trump was the first major US political figure to talk consistently in the hyper-nostalgic language of retrotopia, and he did so using overtly racist, sexist and xenophobic appeals to paint a vision of a society in which the power of white men would once again be resurgent. This strategy, though not sufficient to secure the popular vote, resonated with tens of millions of anxious voters who heard in Trump’s retrotopian fantasies a rejection of the idea that the only political option was a suffocating extension of the neoliberal present into the indefinite future. Rather than accept this neoliberal version of the future, even if it was sweetened with tepid incremental reforms, many of them chose to invest their hopes in the imaginary glories of an idealized past conveniently scrubbed of civil rights and environmental activism.

Alas for their delusions. Trump is the ultimate globalist. He simply wants the world to return to the US-led colonial order of 1950s Eisenhower-era capitalism, albeit under a fascistic cult of personality rather than with an avuncular retired general and war hero as national figurehead. It is a fantasy that will be dissolved by acid reality with unpredictable consequences.

On the Road to Hope for an Authentic Future

Realizing early on that it was not possible for the election to end well, I began traveling the world in August 2016 after months of planning, on a journey of educational discovery that in addition to the US, has taken me to 12 nations in Europe and Latin America so far. With an eye on the future, I wanted to learn about projects that are reimagining what is politically possible, so I went looking for fresh ideas and success stories.

The inspiring projects I found exceeded my most optimistic expectations. They consistently exhibit a focus on responding to local conditions with solutions that have the potential to be scaled to connect with larger movements. Among these initiatives, VIC (Vivero de Iniciativas Ciudadanas/Nursery of Citizen Initiatives) in Madrid, Spain, and a national movement to preserve heritage seeds among Mexican campesinos stand out as having enormous global potential. In addition to these two projects, which were the focus of a previous Truthout report, I also encountered inspiring micro-initiatives everywhere else that I traveled, especially in Mexico, where the impact of US policies is felt so strongly.

In Chiapas, Mexico, for example, Antonio de Jesús Anaya Hernández runs a project called Hacking Diem that is creating a global network of hackers who educate university students on truly disruptive tech social innovation to address economic inequity. he has committed to running the project without funding for the first 18 months to ensure the growth of an internal culture grounded in values other than profit.

In Mexico City, architect Jesús López founded the ATEA (Arte Taller Estudio Arquitectura/Art and Architecture Workshop), a nonprofit collaborative platform and workspace for experimentation by architects, artists and urbanists to practice what they call “urban acupuncture.” During a tour of ATEA’s capacious industrial space in the oldest part of central Mexico City, López introduced me to members who were painters, bicycle builders, urban designers, architects and porcelain artists, among many others, all focused on provocative urban innovation and experimentation.

Founder Jésus López of ATEA (Arte Taller Estudio Arquitectura/Art and Architecture Workshop) in Mexico City shows the project’s bicycle workshop to Javier Esquillor, member and co-Founder of VIC (Vivero de Iniciativas Ciudadanas/Nursery of Citizen’s Initiatives) of Madrid. (Photo: Michael Meurer)

Founder Jésus López of ATEA (Arte Taller Estudio Arquitectura/Art and Architecture Workshop) in Mexico City shows the project’s bicycle workshop to Javier Esquillor, member and co-Founder of VIC (Vivero de Iniciativas Ciudadanas/Nursery of Citizen’s Initiatives) of Madrid. (Photo: Michael Meurer)

In Guadalajara, human rights attorney Ana Paula Barragan Gutiérrez is running a non-profit pilot project through her Aurora Global organization in one of the poorest barrios in the city in which residents partner with tech experts to solve problems specific to their barrio with locally appropriate technology. The methodology is being documented to ensure that this kind of localized tech transfer can be replicated in other barrios across Latin America.

In Argentina, attorney and historian Sergio Carciofi started a project called Pasos Previos Casares in his hometown of Carlos Casares to teach young people civic responsibility. Carlos Casares is a unique city with a population split almost evenly between residents of Catholic Italian heritage and Jews. The common civic religion that has always bound them is Peronismo, so his project uses Peronismo as a vehicle for civic engagement. In a little more than 18 months, Pasos Previos activists have managed to pass a citywide ban on the use of plastic bags and implement a ban on dangerous fireworks, all with broad public approval. Now the city of Buenos Aires is consulting with Carciofi and his young cohorts to implement similar measures in the nation’s largest city.

Argentine historian, activist and attorney Sergio Carciofi is creating highly effective new civic initiatives based on popular tenets of Peronismo. (Photo: Michael Meurer)

Argentine historian, activist and attorney Sergio Carciofi is creating highly effective new civic initiatives based on popular tenets of Peronismo. (Photo: Michael Meurer)

In Medellín, Colombia, language teacher Milena Palacio started a volunteer program with no funding called Stairway to English in Comuna 13, teaching English, art and dance gratis to residents four times weekly. Comuna 13 has been one of the most violent barrios in Latin America in the past. Three years after starting, Palacio’s project has empowered residents to start their own tiny film festival, mount public dance performances and give guided tours of the Comuna in English for socially-conscious tourists.

Milena Palacio, founder of the “Stairway to English” project in Medellín, Colombia, poses with schoolchildren in Comuna 13, the at risk barrio where she teaches English. (Photo: Michael Meurer)

Milena Palacio, founder of the “Stairway to English” project in Medellín, Colombia, poses with schoolchildren in Comuna 13, the at risk barrio where she teaches English. (Photo: Michael Meurer)

From Diego Pizarro Martínez, an activist in Chile who lived among the native Mapuche for three years, I learned about the resurgence among tribes of an ancient concept called “trafkintu” that mirrors the seed exchanges I found in Mexico. In premodern Mapuche culture, there were regular trafkintu to allow different tribal branches to share knowledge and goods, including food and seeds. In this native economic model, seeds were considered to be gifts, and the exchange was an expression of friendship to build communal bonds among tribes. There was no quid pro quo. This native social-economic tradition is being revived across the Andes as a de facto counterweight to the corrosive ethos of modern consumer culture.

Artifacts from the Museum of Pre-Columbian history in Santiago, Chile, display the kinds of handicrafts that the Mapuche tribe in Chile is once again exchanging, along with seeds, as part of their reinvention of the ancient “trafkintu” economic tradition. (Photo: Michael Meurer)

Artifacts from the Museum of Pre-Columbian history in Santiago, Chile, display the kinds of handicrafts that the Mapuche tribe in Chile is once again exchanging, along with seeds, as part of their reinvention of the ancient “trafkintu” economic tradition. (Photo: Michael Meurer)

While the large number of promising social initiatives that can be found across the globe is heartening, there is serious work ahead that requires major changes in the way political strategy is conceived and executed on the left. Creating a civic life strong and diverse enough to counter and supplant the current destructive ethos of globalized neoliberal capitalism requires full political engagement of a kind that is very different from simply voting.

Reimagining Work and Rediscovering Joy

Mexican farmer and organizer Alan Carmona Gutiérrez, a cofounder of a civic organization named Un Salto de Vida (A Leap of Life), describes the way that cynically hip capitalist modernity has made the word “peasant” an archaic term of opprobrium and backwardness, but he finishes his thought with the declaration that it is nonetheless better to aspire to be a peasant (campesino) than a worker (obrero), because the former suggests a way of inhabiting the Earth that does not imply its destruction “for the profit of a few.”

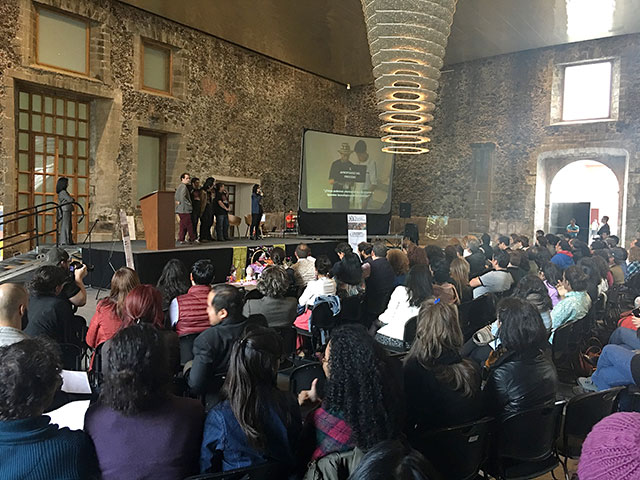

A poster at the National Library for a series of Open Labs fora on the theme of “Cities that Learn.” (Photo: Michael Meurer)The worker is part of the monetized economy. The modern peasant is part of civic society. He or she is not alienated from his or her own history, but connected to the future through the prism of a lived past.

A poster at the National Library for a series of Open Labs fora on the theme of “Cities that Learn.” (Photo: Michael Meurer)The worker is part of the monetized economy. The modern peasant is part of civic society. He or she is not alienated from his or her own history, but connected to the future through the prism of a lived past.

This is an important distinction that the modern left must understand if it is to grow. The joyless, decades-long, quasi-Marxist fixation on the language of factory labor, workers and jobs is out of date. It is its own kind of retrotopianism.

In this era of distributed workforces and digital mobility, services account for more than half of all global economic output. Even in China, manufacturing accounts for less than 15 percent of employment, and global manufacturing has been declining as a percentage of GDP for decades.

Outdated industrial-era thinking that insists on using assembly-line factory models as the primary reference point does nothing to inspire or illuminate the kinds of small scale, often joyful civic actions and creative mindset that are necessary to advance humanity’s cause. In this one sense, the anarchists who insist that life is ludic make a valuable point. To play is to create, and more people need to be empowered to think and act creatively. This crucial, foundational element of human life cannot simply be ceded to the market, where it inevitably morphs into disempowering consumer spectacle.

A photo of Mexican poet Octavio Paz is displayed at an Open Labs forum on new civic initiatives in Mexico City in tribute to the creative spirit in politics. (Photo: Michael Meurer)Unless the modern left can understand human desire and imagination in new ways, it cannot be successful at energizing and inspiring people in a different direction from the endless stream of ephemeral excitements offered by advanced late-stage capitalism. As Lacanian philosopher and film analyst Todd McGowan says,

A photo of Mexican poet Octavio Paz is displayed at an Open Labs forum on new civic initiatives in Mexico City in tribute to the creative spirit in politics. (Photo: Michael Meurer)Unless the modern left can understand human desire and imagination in new ways, it cannot be successful at energizing and inspiring people in a different direction from the endless stream of ephemeral excitements offered by advanced late-stage capitalism. As Lacanian philosopher and film analyst Todd McGowan says,

Capitalism writes itself on top of the logic of desire, which is why it has been so successful as a socioeconomic system and why it appears eternal. But at the same time, capitalism hides from us the trauma inherent in our desire…. The satisfaction that capitalism produces stems from the incessant failure of desire to realize itself …

The paucity of new ideas about work and play on the left is already at a crisis point. Global capital has outflanked ossified leftist political theory by inventing a so-called “sharing economy” in which human subjectivity itself has become the product. Under this new “cognitive capitalism,” even the interactions of friendship and hospitality have been monetized as commodities.

In sharp distinction to this financialization of subjective life, the emerging collaborative civic sensibility symbolized by many of the projects that I learned about throughout Europe and the Americas, and the national campaign to protect heritage seeds and sacred Mother Earth among Mexican campesinos, are predicated on authentic sharing and vibrant communal attachment to life in the elaboration of a common cause with others. They are also the opposite of retrotopianism.

As Alan Carmona Gutíerrez eloquently stated in a recent newsletter from his organization, the goal is to neither abandon nor idealize our history, but to “listen, observe and understand the past in order to construct a future full of life and dignity.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.