Part of the Series

Despair and Disparity: The Uneven Burdens of COVID-19

On April 6, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed an executive order allowing “medically vulnerable” incarcerated people to be temporarily released on medical furlough for the duration of the state’s disaster proclamation. Furloughs are typically temporary releases from prison, usually for no more than 14 days. Pritzker’s executive order extends the order indefinitely during the pandemic; it is unclear whether people will be expected to return to prison once the pandemic is past.

For 76-year-old Pearl Tuma, who is serving a life sentence at Logan Correctional Center, the governor’s order might be the only opportunity she has to rejoin her family. Imprisoned since 1980, Tuma is one of the oldest women in Illinois’s prison system. Now, she suffers from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, cataracts, arthritis and a degenerative spine condition. She must use a wheelchair to get around the prison. She has applied for clemency numerous times under several governors; each time, she has been denied.

“I am very fearful that if COVID-19 comes into this prison, there is no safe place for anyone,” wrote Tuma from prison. “Our living conditions are deplorable and unsanitary. We are 66 inmates to a wing, one ‘toilet’ area per wing. It’s our only means to wash our dishes, wash our hands or brush our teeth.”

At Logan, as in nearly all prisons, it’s impossible to follow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines to frequently wash hands or practice social distancing. “There is a foam soap dispenser in the toilet area that is refilled maybe once a week,” Tuma wrote. “It’s almost always empty. Sixty-six women use it how many times a day? They tell us to cope by limiting ourselves to three showers per week.”

As the numbers of confirmed coronavirus cases climb inside the nation’s jails and prisons, incarcerated people and their family members fear for their lives. In response, some elected officials are pledging to reduce jail and prison populations to prevent the rapid spread of coronavirus in overcrowded facilities. But are they actually fulfilling their promises?

California Announces Potential Release of 3,500 People From Prison

California made headlines with its announcement that officials planned to consider releasing up to 3,500 people from its prison system, which is operating at over 130 percent capacity. However, those 3,500 people are within two months of their parole dates and do not include people with violent or sex offense convictions. California Gov. Gavin Newsom also halted the transfer of people from county jails to state prisons for 30 days, which will temporarily stop approximately 3,000 new arrivals at the prisons (though it will simply keep people in jails, as opposed to releasing them).

Newsom has publicly rejected the idea of releasing large numbers of people early. California state attorneys asked federal judges not to intervene and order prison releases, although more than a dozen prisons are severely overcrowded, hovering between 140 to 169 percent capacity.

At a mid-March press conference, Newsom said that doing so would exacerbate homelessness and strain the health care system. “I have no interest, and I want to make this crystal clear, in releasing violent criminals from our system, and I won’t use a crisis as an excuse to create another crisis,” he stated. “That’s not the way we will go about this. We will do it in a very deliberative way.”

Four days later, however, he issued 21 commutations to people in prison, including people serving life sentences on convictions such as murder and manslaughter. His press release noted that Newsom had considered each person’s health status in his decision.

The announcement caused a stir and a flurry of hope within the prisons. “The LADIES ARE ALWAYS EXCITED ABOUT THE COMMUTATIONS because it gives them hope for themselves,” Lynda Axell, a 66-year-old who has been imprisoned since December 1989, told Truthout via email, “but there are always the feelings of WHY NOT ME?”

In Kentucky, the Governor Commutes 1,000 Prison Sentences

Kentucky prisons have reported less than 20 positive cases of coronavirus (nine incarcerated people and five employees). But even before those cases came to light, Gov. Andy Beshear announced that he was commuting the sentences of approximately 1,000 people with nonviolent convictions in state prisons to decrease the chances of coronavirus spread. (Kentucky prisons confine approximately 12,000 people.) His commutations were limited to two categories: people who have either health conditions, such as respiratory illnesses or heart conditions, or people with less than six months remaining on their prison sentence. Still, that’s better than Oklahoma, where Gov. Kevin Stitt initially made headlines when he announced that he was granting 450 commutations. Oklahoma currently has nearly 25,000 people in its state prisons, which have been plagued for years by overcrowding and understaffing.

However, the actual number of people released from the state’s bloated prison system will be closer to 100. The majority of the governor’s clemency recipients have other charges for which they must still serve prison sentences.

In Minnesota, Gov. Tim Walz has not committed to reducing the state’s prison population. During his live-streamed address on Friday, April 3, however, prison commissioner Paul Schnell stated that officials were reviewing people with nonviolent convictions and within 90 days of their release date.

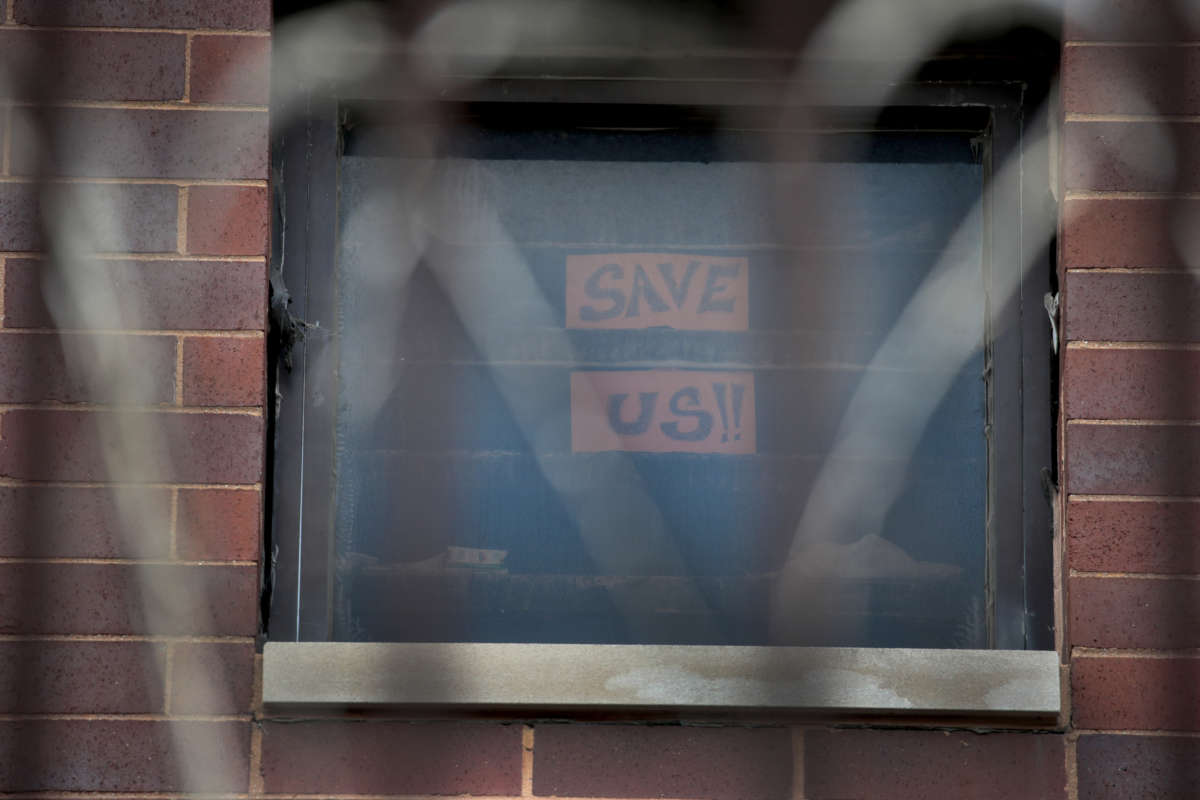

Inside Minnesota’s women’s prison at Shakopee, incarcerated people are fearful that such a measure will be too little, too late. In some housing units, four people are confined in cells originally designed for two. “I can reach over and touch my roommate,” one woman, serving her first year of a four-year drug sentence, told Truthout.

“The staff treat us as if we are the threat,” Kendra*, another incarcerated woman, told Truthout in an email, noting that the majority of staff do not wear masks. Kendra’s prison job is cleaning the housing unit; recently, she wrote, staff replaced disposable gloves with reusable rubber kitchen gloves. “We are assigned our own pair,” she said. But, she added, “we are in close contact with staff and vulnerable offenders as we are charged with pushing those in wheelchairs and are constantly cleaning behind everyone and everywhere in the units.”

Many staff members seem indifferent to their potential for spreading the virus. Kendra reported that, in early April, she was present when another incarcerated woman asked an officer why she was not wearing a mask. “You are the threat to bring in the virus,” the woman pointed out. In response, the officer simply said, “That is a lie.”

Kendra is less worried about her own health than about being an asymptomatic carrier, especially because her cellmate is an older woman with health problems and relies on others to push her wheelchair. “I don’t want to kill someone … and shouldn’t be put in that position,” she reflected.

Kendra’s husband, who asked not to be named in publication, worries about her health and safety. His biggest fear, he told Truthout, is that she’ll contract the virus. “Some people might be feeling symptoms, but they’re afraid to tell anyone because they don’t want to be put in isolation. That’s the place where you go if you break the rules,” he said, referring to solitary confinement. “That’s not humane.” He lives on a farm 10 miles from a hospital affiliated with the Mayo Clinic; if Kendra were to feel sick, he said, “she would get better medical attention out of prison than in prison.”

In other states, governors are passing the buck. Rather than using his clemency pen, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine initially asked judges to consider releasing 38 people with nonviolent convictions from the state’s prisons. Twenty-three of those people are either pregnant or had recently given birth while in prison; the others are over the age of 60 and within 60 days of being released. Eleven days later, after the death of a staff member and an incarcerated person, he asked a bipartisan panel of lawmakers to recommend releasing another 141 people. Ohio’s 31 prisons currently incarcerate 48,991 people.

In Pennsylvania, where the governor has the power to grant reprieves (temporary suspension of prison sentences) as well as commutations, Tom Wolf has chosen to do neither. Instead, his administration is drafting legislation to allow the release of imprisoned people serving short sentences for nonviolent, low-level convictions and who are deemed medically vulnerable. The legislation does not include people who are elderly — a population which, according to Legislative Director Sarah Speed, “are almost exclusively serving life sentences or are sex offenders.” The 44,600 people in Pennsylvania’s 25 prisons are now on lockdown after an incarcerated person tested positive for coronavirus. After 11 incarcerated people and 18 staff members tested positive for — and one incarcerated person died from — COVID-19, the governor stated that he will use his reprieve powers for people who are medically vulnerable and have less than 12 months left on their sentence. Those convicted of violence, however, will remain ineligible.

Some governors have no plans to reduce state prison populations through early release or commutations. “We have no measures to lessen crowding in state prisons,” New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who has issued 21 commutations during his nine years in office, said at his April 3 press conference. “But reducing the prison population? We don’t have any way to do that right now.” That same day, he signed the state budget which included rollbacks to the state’s newly enacted bail reform. These changes, which Cuomo had pushed, add 15 new charges in which a judge can set bail and, as Peter Goldberg, director of the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, noted, will “expand pretrial jailing so thousands more New Yorkers will be subjected to imprisonment and unspeakable harm” during a deadly pandemic.

New York Mayor Authorizes Release of 900 From Jails While Police Arrest for Failure to Social Distance

In New York City, nearly 1,000 people (334 incarcerated people and 657 staff members) in the jails have tested positive for coronavirus, bringing the infection rate to 8.24 percent (compared to 1.36 percent in New York City). The chief physician of correctional health care called it a “public health disaster unfolding before our eyes.” In response, Mayor Bill de Blasio released 900 people from the city’s jail system.

At the same time, however, de Blasio authorized police to enforce social distancing with penalties. Officers are supposed to issue warnings and, as a last result, fines. During the last weekend in March, however, three New Yorkers were arrested and jailed, possibly exposing them to coronavirus while held in overcrowded holding cells.

One woman had been in a parking lot with her boyfriend when police ordered them to leave. Before they had time to comply, officers grabbed her boyfriend and arrested both, according to the woman. She was taken to central booking and held in a cell for 36 hours with two dozen other women. Those who already had masks were allowed to keep them; those who did not were not given any. In addition, she said that the cell was dirty and lacked soap. At one point, an officer distributed drops of hand sanitizer. The woman was released on March 29, but her employer has not allowed her to return to work because of fears she might have been exposed to coronavirus in the cell. Since then, at least 15 people have been arrested, sometimes violently, by the police for failure to social distance.

The de Blasio administration is also interfering with efforts to mitigate risk to jail staff. Though four corrections officers have died from coronavirus, city lawyers appealed a judge’s decision to provide masks and protective gear to jail correction officers at the start of each shift.

“An Incarcerated Person Is a Person”

In Illinois, Governor Pritzker’s executive order comes on the heels of his earlier action — releasing nearly 300 people from prisons on March 31. Among them were 34-year-old Mandi Grammer, her 7-month-old Brenleigh Jolea, and four other mother-baby pairs from the prison nursery in Decatur.

One week earlier, Illinois prisons confirmed the first coronavirus case at Stateville Correctional Center in Joliet. Within five days, 12 incarcerated people had been hospitalized with confirmed cases.

At his March 31 press conference, Pritzker stated, “An incarcerated person is a person, and my administration will not be in the business of claiming one life is more than another.” The release decreased the prison population by less than 1 percent, a reduction that advocates argue is “far lower than the population reduction needed to protect those who remain in custody and the surrounding communities.”

Advocates continued to push the governor to do more. The Uptown People’s Law Center filed a lawsuit, demanding the governor and Department of Corrections immediately release people who are elderly, have serious medical conditions or have already served the majority of their sentences. As many as 13,000 of the state’s 36,000 people could be eligible.

By April 5, the number of confirmed cases in Stateville had risen to 80 — 56 among incarcerated people and 24 among staff, making up the majority of the 102 confirmed cases in Illinois’s 28 prisons. By then, Stateville also had two deaths from coronavirus.

The following day, on April 6, Pritzker announced his executive order. He also commuted the sentences of 17 people, including seven who had been convicted of murder.

For Tuma’s granddaughter, Shanneah Davidson-Welch, that might be reason for hope. Davidson-Welch was already worried about her grandmother even before coronavirus began spreading throughout the country. “She’s already sick and in a wheelchair,” she told Truthout, adding that her grandmother constantly struggles with pain and obtaining proper medical care.

She also notes that Tuma’s arrest and imprisonment stem from being entangled in an abusive marriage in which her husband frequently forced her to shoplift and commit other thefts. In 1979, Tuma was preparing to flee with her young daughter. Fearing her husband’s violence, she obtained a gun. Before she could escape, however, her husband drove her to a department store and ordered her to go inside to shoplift. When she was approached by a store employee, Tuma panicked. She shot (and missed) the store employee. Then, when turning to flee, she shot and killed a store security guard. She was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life without the possibility of parole.

“The main person, my grandfather, was released [from prison] and he’s doing good, following the rules of society,” Davidson-Welch said. “It’s only fair that she has the same opportunity. She deserves a second chance. We deserve to have her be a part of our life. I should be able to experience being around my grandmother.”

*Kendra asked to use a pseudonym to prevent retaliation.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.