At the Tufts Medical Center in Boston, 1,200 nurses recently walked off the job, initiating “the largest nurses’ strike in Massachusetts’s history and the first in Boston for 31 years.”

In New York, lawyers representing farmworkers recently argued in the State Supreme Court that they have a constitutional right to organize.

In the Pacific Northwest, indigenous Oaxacan farm workers have organized the “first new farm worker union in the U.S. in a quarter century.”

In New York City, Fast Food Justice, a new nonprofit, will advocate for fast-food workers on issues affecting members, although they will be forbidden to undertake bargaining wage levels directly with employers.

And in the South, “workers involved in the Southern Workers Assembly are … focused on building a network of smaller minority unions that lack collective bargaining to create a groundswell of union support.”

These encouraging and varying actions to organize workers could portend resurgence in the labor movement in this country — or they may be the final act in the slow death of unions.

Glimmers of hope are matched and sometimes overshadowed by defeats, as when the United Auto Workers union lost a unionization vote last week at the Nissan car plant in Canton, Mississippi by 62 to 38 percent vote. A victory could have led to a revitalization of organizing in the South. Instead, the union’s lack of influence among Southern auto workers serves to reduce its bargaining power to stop plant closings in Detroit and other manufacturing centers.

The future of unions is precarious. Union membership has been in steady decline. The stridently anti-union stance of the Trump administration, Congressional Republicans and state government Republicans, as well as a hostile Supreme Court, pose a substantive threat to union existence.

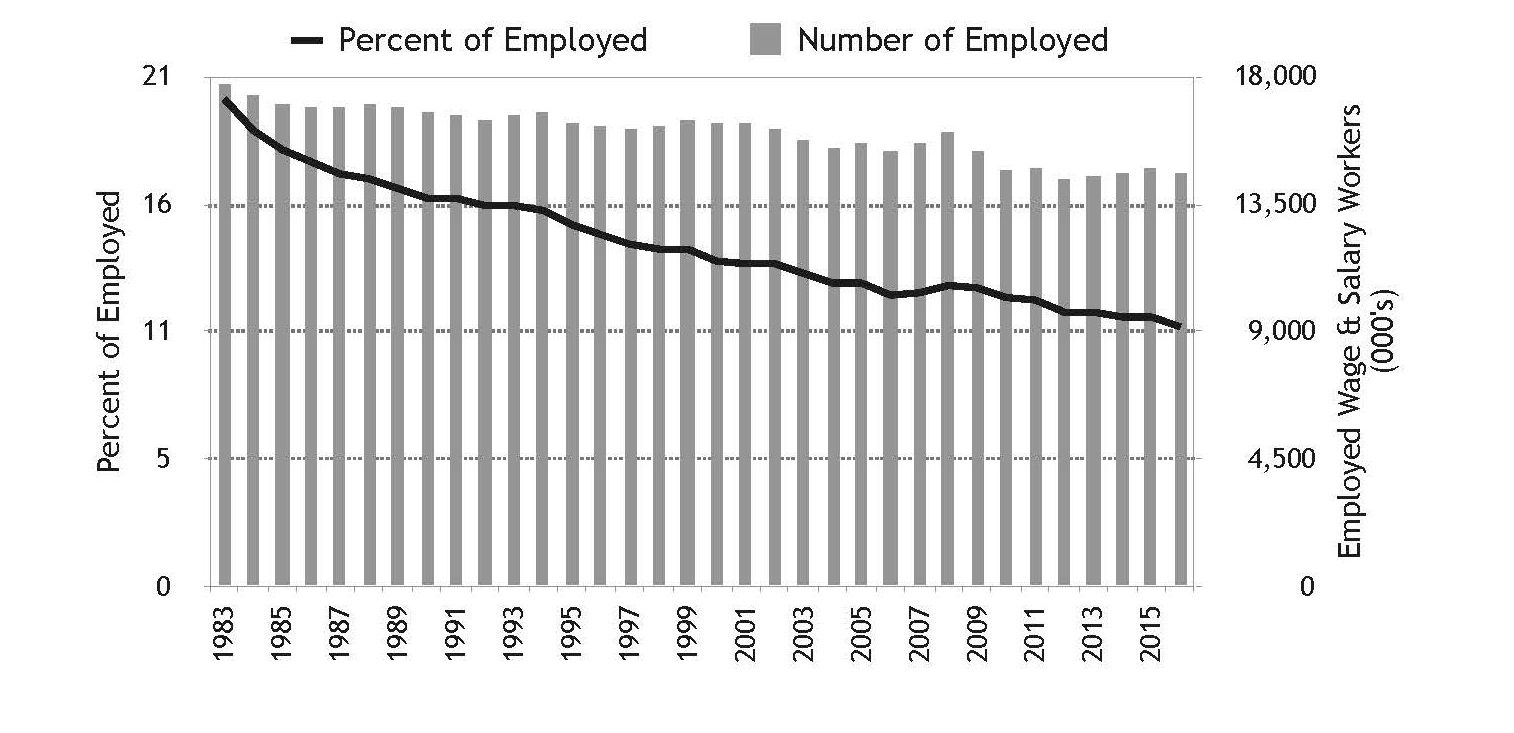

Since 1983, the number of unionized employed wage and salary workers has decreased from 17.7 million to 14.6 million in 2016. As a percentage of total employed wage and salary workers, the decline has been from 20.1 percent in 1983 to 10.7 percent in 2016.

Union Affiliation: 1983 to 2016:

(Source: Current Population Survey)

(Source: Current Population Survey)

Despite his rhetoric during the presidential campaign, Donald Trump’s administration has moved to reverse several pro-labor actions taken by the Obama administration. His proposed budget will decrease funding for the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB, an institution intended to protect workers from employers, and his expected appointment of Republicans to the two vacant seats on the NLRB will likely result in the reversal of various pro-union rulings, including those holding companies responsible for labor violations committed by contractors and franchisees, making it easier for relatively small groups of workers within a company to form a union, and granting graduate students at private universities a federally protected right to unionize.

The Department of Labor is rescinding the “persuader rule” which previously required contractors to disclose if they had hired a consultant to “persuade” employees against joining together in union. And Congress is discussing three anti-union bills: The Workforce Democracy and Fairness Act, The Employee Privacy Protection Act and The Employee Rights Act.

Right-to-work laws now exist in twenty-eight states, including Wisconsin, Missouri, Kentucky, Iowa, and Michigan, once the heartland of American labor. In right-to-work states, workers who are not union members are not required to pay union dues or their equivalent, although they benefit from collective bargaining agreements reached on behalf of all workers in a specific sector. The huge financial burdens placed on unions as a result threaten to undermine their financial viability.

The death of Antonin Scalia forestalled an unfavorable Supreme Court decision that could have doomed unions in the case Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association. With the addition of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court and the pending hearing of a similar case — Janus v. AFSCME — the Court may rule against unions in its next session. A ruling against labor will have the same effect nationwide for public sector workers as right-to-work laws have at the state level.

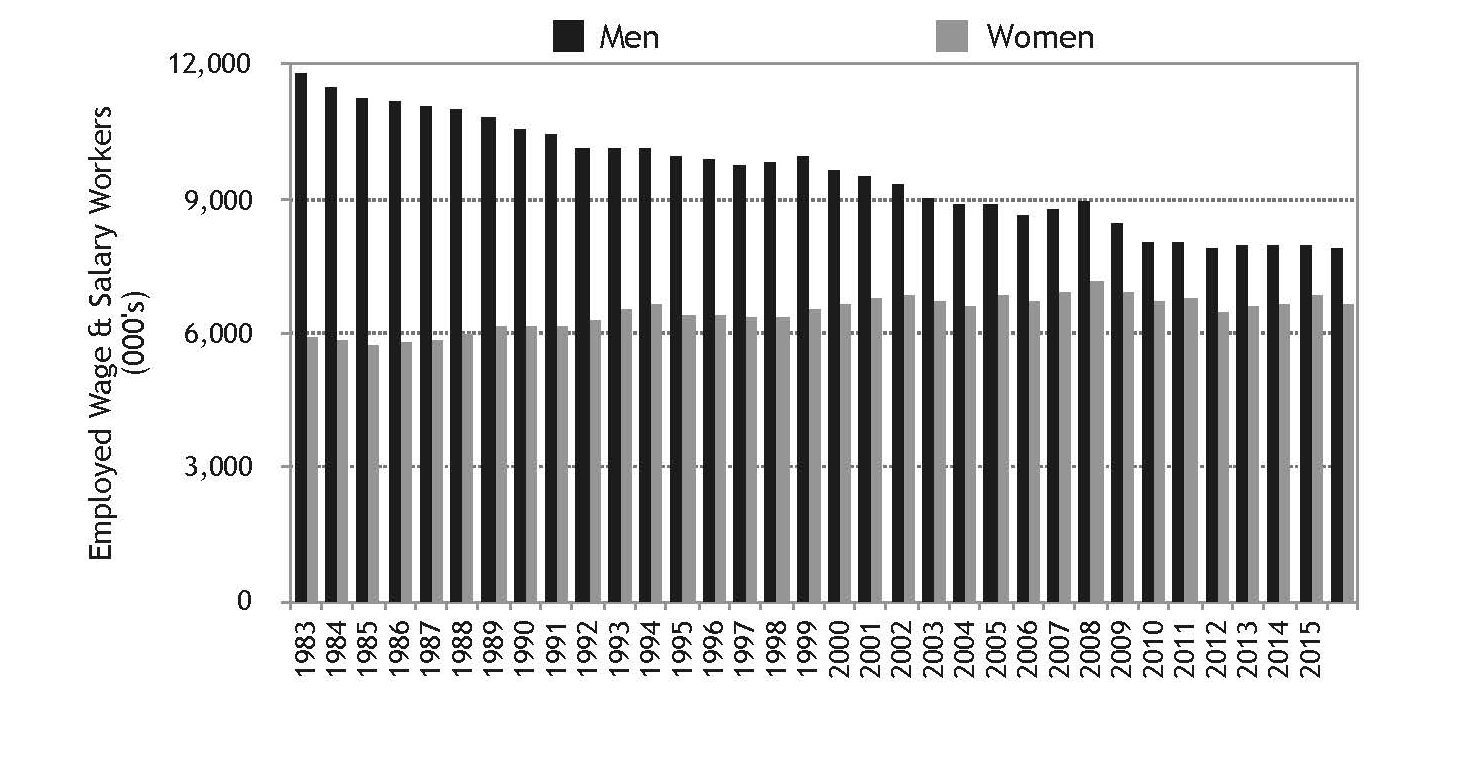

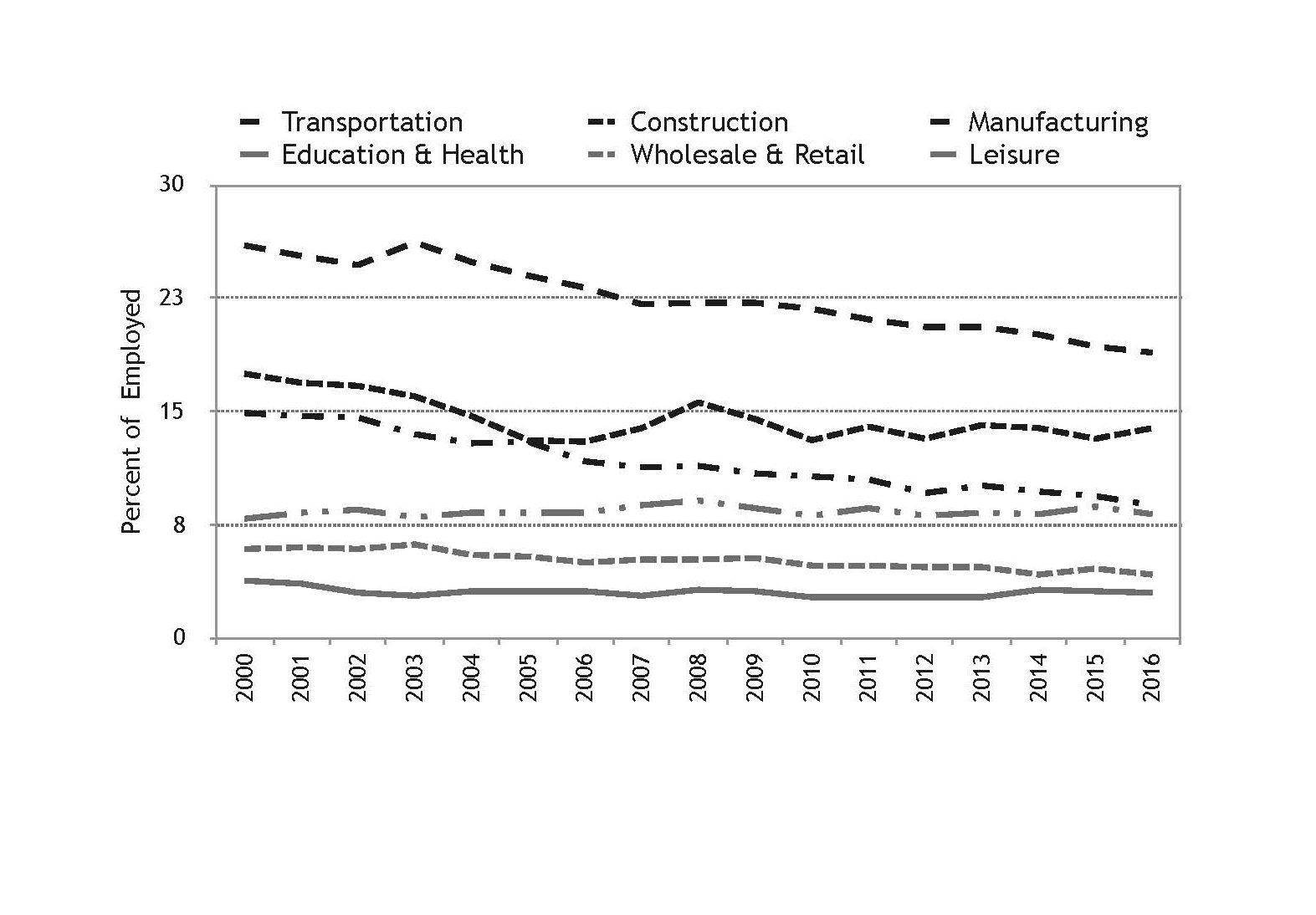

Resisting this threat, unions need to recognize the changing composition of their membership. Whereas union membership was formerly predominantly male, white, and concentrated in the private sector, especially in the transportation, construction, and manufacturing sectors, it is now increasingly female, disproportionately black, and has gained membership only in the education and health sectors, while declining substantially in the transportation and manufacturing sectors. Union membership in the government sector is now almost equal to that in the private sector.

Between 1983 and 2016, the number of male union members decreased by about 4 million — from 11.8 million in 1983 to 7.9 million in 2016. By contrast, the number of women union members has increased by almost 800,000, increasing from a little less than 6 million in 1983 to almost 6.7 million in 2016.

Union Membership: Demographic Composition 1983 to 2016:

(Source: Current Population Survey)

(Source: Current Population Survey)

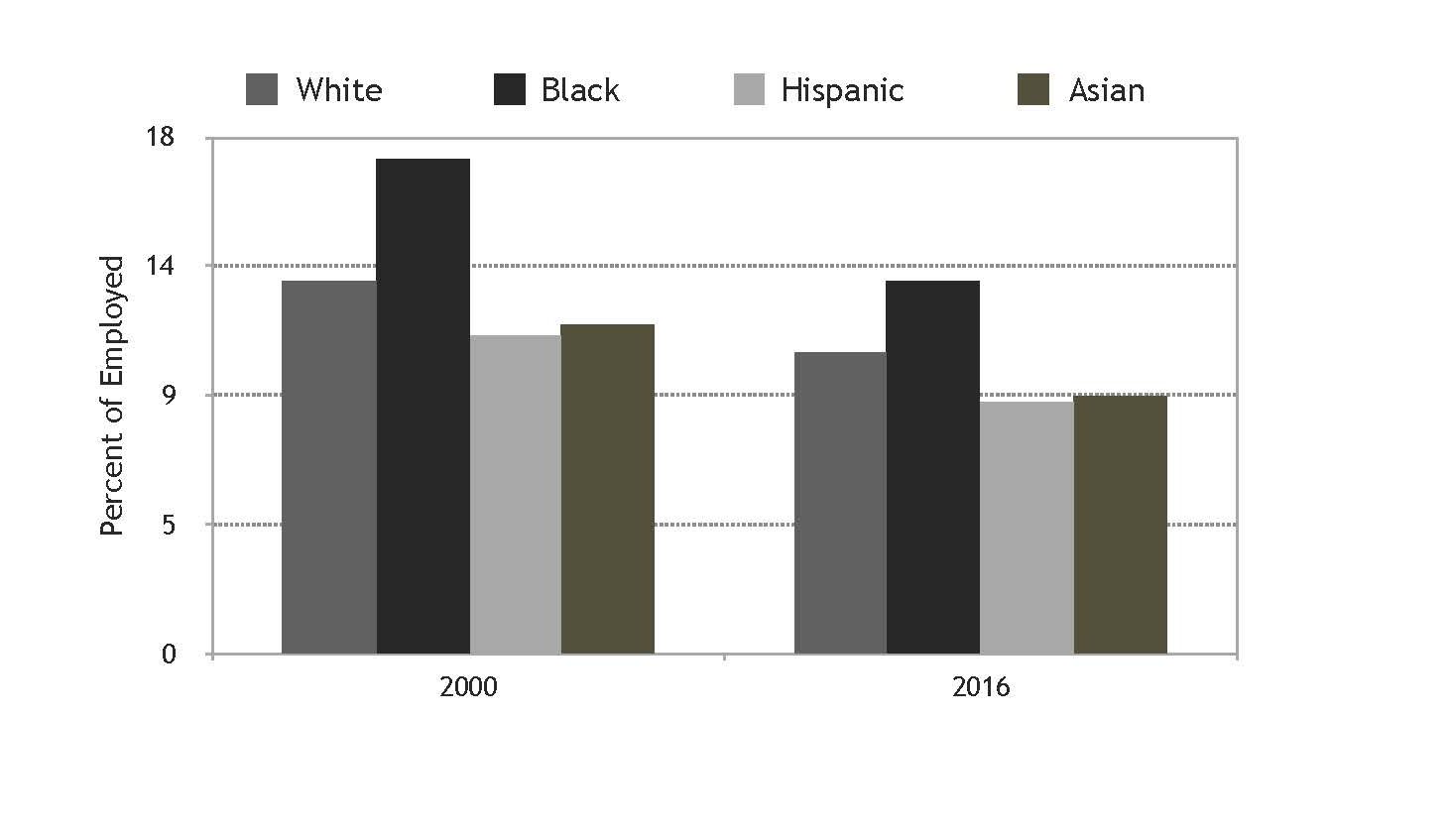

Although the percentage of unionized workers has decreased for all racial and ethnic groups, black unionization rates are proportionately higher than for whites, Hispanics, or Asians. In 2000, about 17 percent of all employed black wage and salary workers were union members; by 2016, it had fallen to 13 percent. By contrast, only 13 percent of white wage and salary workers were unionized in 2000; in 2016, the percentage had fallen to 10.5 percent.

Overall, whites made up 69 percent of union members in 2016, compared to almost 75 percent in 2000; the share of blacks has remained constant at almost 14 percent; the share of Hispanics has increased from 9 percent to almost 13 percent, and that of Asians from 4 percent to almost 5 percent.

Union Membership: Racial and Ethnic Composition, 2000 and 2016

(Source: Current Population Survey)

(Source: Current Population Survey)

Union membership in the private sector declined from almost 12 million in 1983 to about 7.5 million in 2016. By contrast, union membership in the government sector has grown from a little more than 5.7 million in 1983 to 7.1 million in 2016. While only 6.4 percent of all private sector workers were unionized in 2016 — down from 16.8 percent in 1983 — 34.4 percent of government workers were unionized in 2016, slightly less than the 36.7 percent rate in 1983. Within the government sector, 27.4 percent of federal workers were unionized in 2016, 29.6 percent of state workers and 40.3 percent of local government workers.

Union Membership: Private and Government Distribution, 1983 to 2016

(Source: Current Population Survey)

(Source: Current Population Survey)

Among the industrial sectors with higher rates of unionization, membership is still primarily concentrated in transportation, construction, and manufacturing. However, their share of union members declined considerably between 2000 and 2016: in the transportation sector from 26.0 percent to 18.9 percent, in construction from 17.5 percent to 13.9 percent, and in manufacturing from 14.9 percent to 8.8 percent. Although much smaller, membership has fallen slightly in the wholesale and retail sector — from 5.9 percent to 4.2 percent — and in the leisure sector — from 3.8 percent to 3.0 percent. By contrast, union membership has risen slightly in the education and health sectors — from 7.9 percent to 8.2 percent.

Union Membership: Industrial Composition, 1983 to 2016

(Source: Current Population Survey)

(Source: Current Population Survey)

Many of the benefits workers have gained going back to the late 19th century (“eight hours for work, eight hours for sleep, eight hours for what we will”), including unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation, health and safety laws, child labor laws, health and retirement benefits, and others, are a result of the long history of union activity. Unions continue to be a pivotal bulwark against further deterioration in working conditions. Additional threats to unions will further corrode economic security of working people.

The evidence demonstrating the successful achievements of unions is clear. For example, research shows:

- Non-unionized workers, in particular non-unionized men, have endured substantial wage losses with the declining membership of private-sector unions since the late 1970s, exacerbating wage inequality. The most hurt have been non-union men who did not complete college or go beyond high school.

- Membership in unions has raised the wages of black workers and increased their access to health and retirement benefits. They enjoy higher wages and better access to health insurance and retirement benefits than their non-union peers.

- The steady disappearance of the middle class is a direct outcome of the decline in union membership. Research shows that, between 1984 and 2014, almost half of the decline in the middle-class workers can be attributed to a weakening labor movement, in turn contributing to rising inequality.

- The decline in unionization among the working poor is the most important state-level influence on individual working poverty, larger than the economic performance or social policies of the state as well as many other individual predictors of poverty — “where unions are weak, working poverty is widespread and where unions are stable, working poverty is much less common . . . the striking decline of unionization in the U.S. has stalled what might have been progress in reducing working poverty.”

- A comparative international analysis found “strong evidence that lower unionization is associated with an increase in top income shares in [twenty] advanced economies during the period 1980–2010,” although causality is difficult to establish.

- Research by the Economic Policy Institute supports the correlation.

Union Membership and Share of Income Going to the Top 10 Percent, 1917 to 2015

(Source: Adapted and updated from EPI)

(Source: Adapted and updated from EPI)

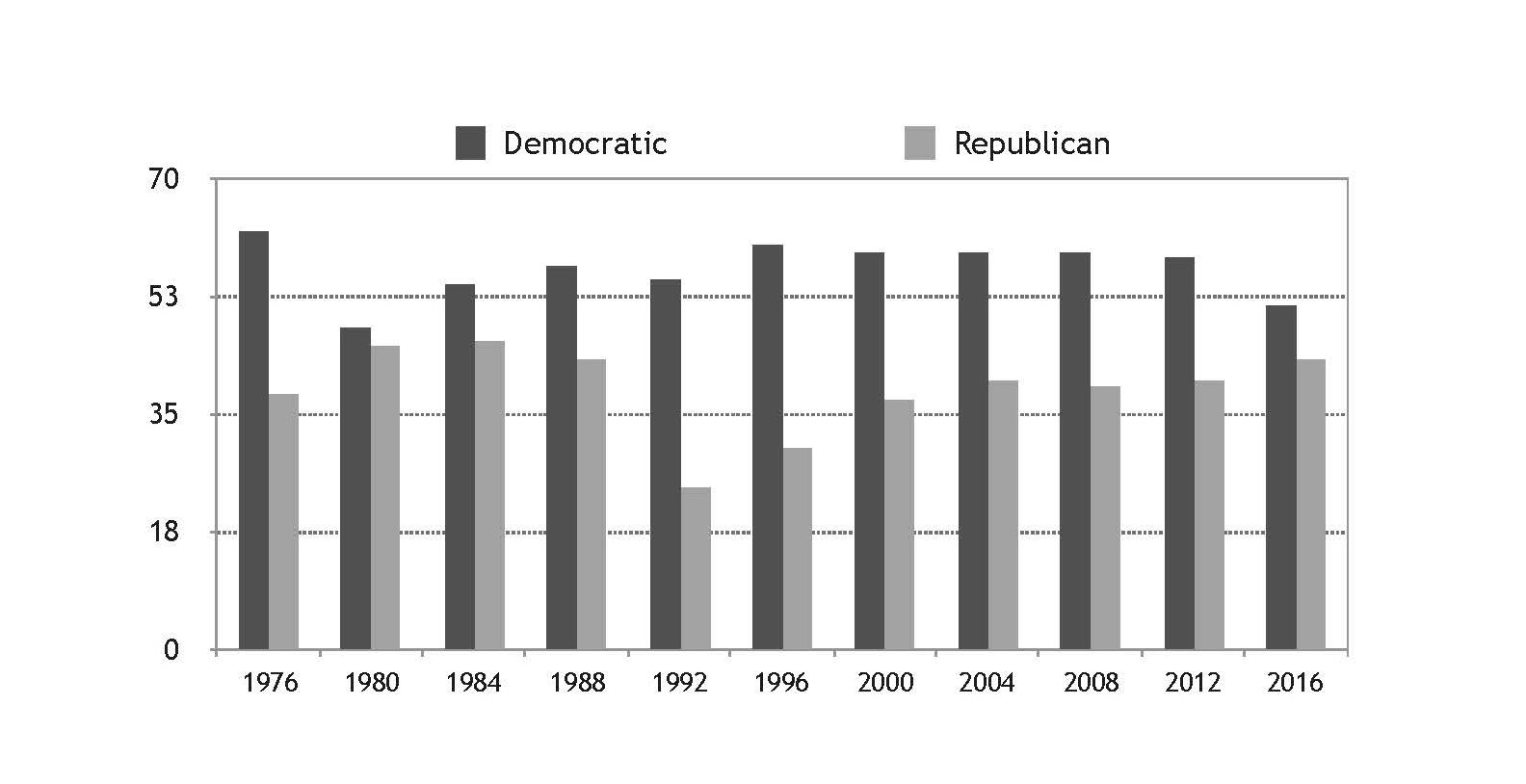

The union-household vote for Hillary Clinton in the recent presidential election was the lowest for a Democrat since Jimmy Carter won only 48 percent of the union-household vote in his defeat by Ronald Reagan. Only 51 percent of union households voted for Clinton, while Donald Trump won 43 percent, more than any other Republican candidate since Reagan in 1980 and 1984.

White workers, especially union workers in Iowa, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, many of whom had voted for Obama, backed Trump, casting the decisive votes to secure Trump the presidency. While Obama won white union workers by a margin of 18 percent, Hillary Clinton did so by only 8 percent.

Union Household Vote in Presidential Elections, 1976 to 2016

(Source: Roper Center; Note: Doesn’t always add up to 100 percent)

(Source: Roper Center; Note: Doesn’t always add up to 100 percent)

The Democratic Party recently announced “A Better Deal” for working people in the United States. Writing in the New York Times, Senator Chuck Schumer claimed that “Democrats will show the country that we’re the party on the side of working people.” Similarly, Nancy Pelosi in the Washington Post wrote, “Americans deserve better than the GOP agenda, so we’re offering a better deal.”

Aside from criticism of the slogan, the Democrats have received guarded support for this initiative from parts of the left, accompanied by harsh criticism for some of the policy proposals, as well as dismissal from other sections of the left.

Noticeably absent from “A Better Deal” is any mention of unions. Maybe the Democrats still have much to learn from Jeremy Corbyn’s achievement in the British election. In its election manifesto, the British Labour Party makes clear that in striving for “a fair deal at work,” it will “empower workers and their trade unions — because we are stronger when we stand together.”

Thank you for reading Truthout. Before you leave, we must appeal for your support.

Truthout is unlike most news publications; we’re nonprofit, independent, and free of corporate funding. Because of this, we can publish the boldly honest journalism you see from us – stories about and by grassroots activists, reports from the frontlines of social movements, and unapologetic critiques of the systemic forces that shape all of our lives.

Monied interests prevent other publications from confronting the worst injustices in our world. But Truthout remains a haven for transformative journalism in pursuit of justice.

We simply cannot do this without support from our readers. At this time, we’re appealing to add 50 monthly donors in the next 2 days. If you can, please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly gift today.