California’s prison system is in a state of crisis. Routine violations of incarcerated people’s Eighth Amendment protections from cruel and unusual punishment — including a lack of medical care, overcrowding and ongoing endangerment of incarcerated people with dramatic COVID surges — are compounded by climate-induced disasters that result in losses of power, water and food.

What’s more, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) has repeatedly failed to evacuate incarcerated people for weather-related emergencies in recent years, disregarding their human rights.

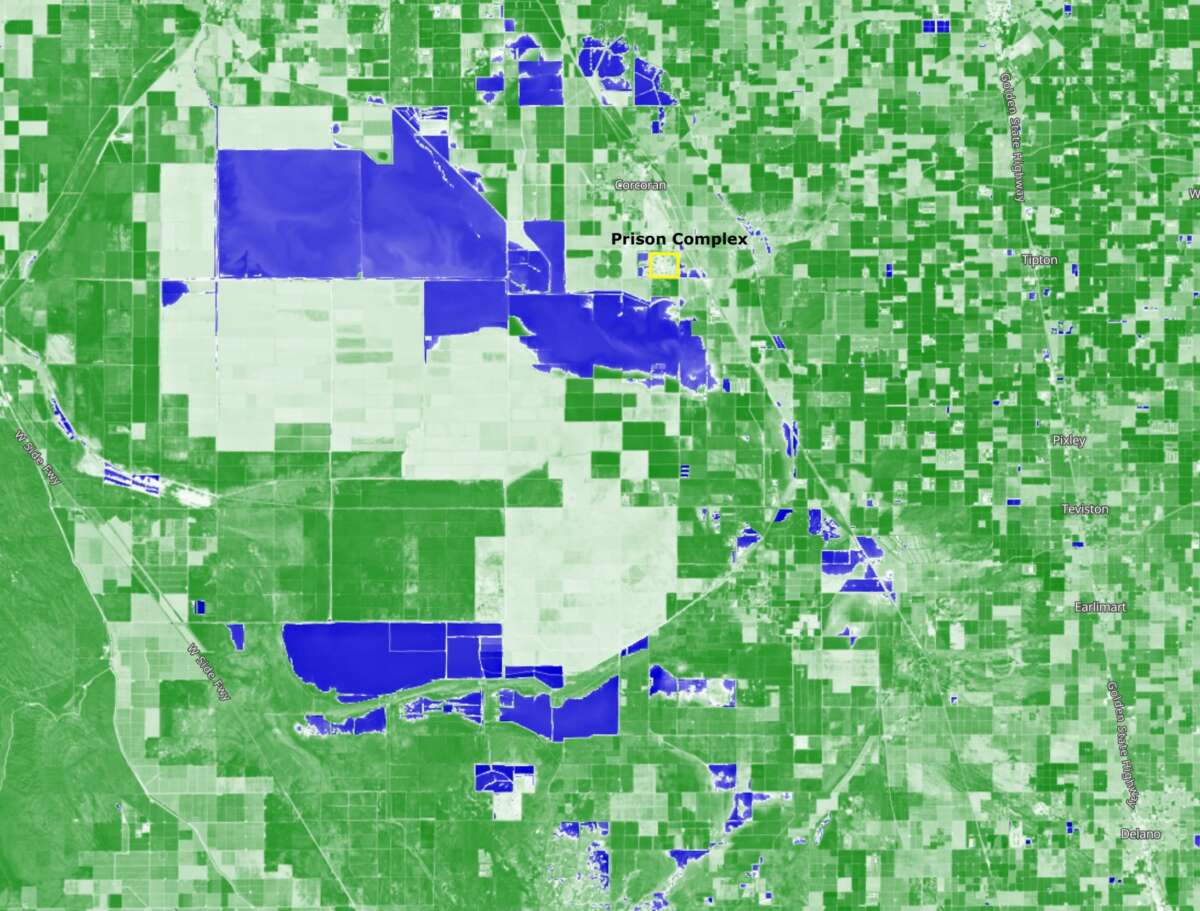

These crises are set to come to a head in coming weeks in Corcoran, California, where the refilling of Tulare Lake has created an imminent danger of flooding at two already-crumbling and overpopulated state prisons. This spring’s slow-moving flooding disaster is projected to hit the largest prison in the state, California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility, and the connected California State Prison-Corcoran, caging a total of 8,138 people.

More than 8,000 People Are Incarcerated in the Middle of a Historic Lakebed

The two state prisons in Corcoran — California State Prison-Corcoran (CSP-COR) and Substance Abuse Treatment Facility and State Prison (SATF) — are located side by side at the southernmost edge of the city of Corcoran. The two prisons were built after the largest floods in Corcoran’s recent history, which occurred from January to July of 1983. These two prisons have not withstood this type of flooding before. This year, a deluge of atmospheric rivers and unprecedented snowfall have created never-before-seen conditions for the buildings and infrastructure of these two prisons.

To the west of the two prisons is the advancing shoreline of the refilling Tulare Lake, which is currently about two miles away. While it may seem far-fetched for the shoreline to move this rapidly, projections for this year’s growth of the Tulare Lake include parts of Fresno, which is 40 miles north of the current lakeshore. As Californians are certainly aware, climate change causes a whiplash of record precipitation on one hand, and record-high temperatures in the summer on the other hand. The lake’s growth is not steady or predictable; instead, it depends on a series of interrelated factors: rainfall, rate of snowmelt, rate of runoff from the Sierras, diversion efforts of the rivers and streams, the release of floodwater onto farming lands, and levee maintenance to protect residences.

In between the current boundaries of the lake and the prisons is land owned by J.G. Boswell Company, one of the largest cotton producers in the world. The company has been under fire in the past two weeks for using its extensive irrigation system to keep its own prime land at the basin of the historic lake dry and backing up water along the rivers feeding into the lake, which has resulted in flooding in residential areas and other farmers’ land.

In fact, the two prisons are located on idle farmland sold to the state by J.G. Boswell in 1985, particularly because the area was prone to flooding. Evidently, the risk of floods at this site is older than the prisons themselves, but no evacuation plan exists for the people locked up in them.

To the east is the growing Tule River, coursing down from the Sierras. During the storms in late March, a canal shooting off from the Tule River breached its levee at the area closest to the prison complex, about half a mile away at the intersection of Paris Avenue and Plymouth Avenue. This flooding has made parts of Highway 43 inaccessible and many people have been stranded in flood waters south of Corcoran. Incarcerated people in the California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility report that the road closures extended the trips of their visiting family members, and worsened staffing shortages. On March 26, 2023, the water continued to rush over the levee near the prison, while a lone tractor and a few construction workers attempted to reinforce the levee upstream.

Tulare Lake: 1983 vs. Today

The last comparable flood of the Tulare Lake Basin occurred in 1983, before either prison was built. The 1983 flood was caused by a total runoff of about 6 million acre-feet of water from reservoirs and snowmelt in the Sierras into the Tulare Lake Basin. This year’s snowpack and reservoir measurement is about a million acre-feet more than it was in 1983, meaning that this year’s runoff and flooding will likely be greater than anything seen in the past 40 years.

Changes in the area’s topography since 1983 have also made the basin region more susceptible to flooding. Agricultural groundwater pumping has hollowed out the underground aquifers and dropped the ground level unevenly throughout the historic lake basin, a phenomenon known as subsidence. Subsidence caused by overdrawn groundwater around the city of Corcoran has led to a drop of 11.5 feet since 2007 in some places. Although some explain subsidence as a natural byproduct of the drought, J.G. Boswell Company has the highest number of wells and the deepest wells in the area, as well as the most cotton plants to water. The amount of water pumped by this company is not publicly available, but its unmatched water-pumping capital outlay indicates a commitment to groundwater usage. Boswell’s unsustainable aquifer pumping and safeguarding of its own farmland continues to endanger incarcerated people and residential areas of Corcoran, Allensworth and Alpaugh.

In addition to the total increased risk of flooding in the region, subsidence around the Tule River to the east of Corcoran has also merged two flood plains near the prison, the Deer Creek and Tule River flood zones, which are just south of the prison complex. The merging of these two floodplains makes it more difficult to siphon water away from the prisons, which are caught in the middle of the Tulare River and Deer Creek.

The historic droughts of the past two decades have made levees less effective at managing flood waters, because as the levees are dried out they lose structural integrity and are more likely to spread. Thousands of miles of levees throughout the Central Valley have been a concern for civil engineers, and amid the devastation of the levee collapse in Pajaro, California’s small cities and towns are applying for funding to rebuild and strengthen their levees. The city of Corcoran rebuilt its levee in 2017 to protect from Tulare Lake’s possible re-emergence, but city officials say that it might not be enough to protect their town. The city is scrambling to raise the levee by an additional four feet across its entire 15-mile length, which is dependent on federal funding and working against the clock of the incoming snowmelt.

Kings County was not included in the presidential disaster declaration for California, although it is one of the areas of the state most vulnerable to residential flooding. Nearby Kern and Tulare counties were included, which makes them eligible for federal disaster emergency benefits.

The prison sits right along the southern border of the town’s levee, and if it breaks, incarcerated people will be the first to know.

Failed Evacuations, Failing Infrastructure and Continued Overcrowding

The 8,000 people incarcerated in CSP-COR and SATF will be in extreme danger if flood waters approach the prison, because of the CDCR’s poor management of evacuations in recent years and the already failing infrastructure of the two prisons. Although no California state prisons have been flooded in recent history, the CDCR has repeatedly failed to evacuate incarcerated people during natural disasters, most notably during the 2020 Vacaville and 2021 Dixie fires.

In 2020, a swath of Vacaville was designated for evacuation by the city’s police force, with two state prisons squarely in the middle of the evacuation zone. The CDCR did not evacuate any of the thousands of prisoners in these two facilities, and some of the facilities didn’t have functioning filtration or air-conditioning systems at the time.

The following year, the second-largest fire in California history occurred next to two prisons in Susanville. Again, there was no plan for evacuating the prisons. Incarcerated people held in one block of the California Correctional Center suffered from water and power outages for nearly a month. Both the Vacaville and Susanville crises happened in the middle of the summer, when extreme heat compounds with particulate matter from wildfire smoke to create nearly unbearable conditions inside prison cells.

Equally concerning in the face of a likely flood this spring are the indictments by the Legislative Analyst’s Office of these Corcoran prisons’ failing infrastructure. According to a contracted study for the CDCR, CSP-COR requires $470 million in repairs while SATF requires $278 million. Details concerning each prison are not available to the public, but given the extensive reporting on health and infrastructure issues in similar facilities, it is likely that the air filtration, thermal regulation and structural integrity of these prison facilities do not meet regulatory standards. These types of infrastructure problems can quickly become disasters for incarcerated people when climate crises hit, leaving them unable to flee or fend for themselves and often, trapped in cells without access to basic necessities.

The lack of electricity and water for incarcerated people in Susanville was certainly related to the failing infrastructure, as many incarcerated people testified during the legal battle over the prison’s closure last year. About 100 people incarcerated in Susanville submitted in favor of closing the prison, attributing their ailments to structural problems with the facility. In the incarcerated people’s amicus brief, one person “wrote that he and his fellow prisoners ‘could see the flames of the fire from our windows’ at the same time that prison staff indicated there was no intent to evacuate them … other incarcerated residents reported that the fire exposed them to constant, inescapable smoke inhalation.” The wildfire disaster in conjunction with the pre-existing structural issues of the prison made the facilities nearly unlivable.

A final concerning factor is the fact that the Substance Abuse Treatment Facility is severely overcrowded. The prison, sitting on the southern side of the complex, is currently at 137.1 percent of its designed capacity, in violation of a 2011 U.S. Supreme Court order to reduce overcrowding in California prisons. SATF is also one of 10 prisons that the organization Californians United for a Responsible Budget is urging Gov. Gavin Newsom to close by 2025, because of its unsafe health conditions, overcrowding, geographic isolation, costs, and the rate of homicide/suicide.

When the snowpack melts and the Tulare Lake basin begins to fill at a faster rate, one of the biggest concerns for incarcerated people is how evacuations will work for those in wheelchairs, walkers, and with other mobility restrictions. People with disabilities are housed on the first floor of the SATF because it is easier for mobility, but this puts them more at risk in the event of flooding. On the whole, almost 20 percent of California’s incarcerated population is over the age of 55, and these people are likely to have disabilities and suffer from chronic conditions.

An incarcerated person at SATF spoke to Truthout anonymously for fear of retaliation. He described his distrust of the CDCR’s ability to safely evacuate all incarcerated people in a flooding situation, in part because of the needs of people with disabilities held in the prison, and because of the flooded roads that are already impeding access. “We haven’t heard much about the flooding other than what’s on the news. The staff haven’t expressed any concerns or told us anything; nothing at all.”

What Happens When Prisons Are Flooded?

From the investigative coverage of prisons during hurricanes in the southern U.S., it is clear that floods and power outages wreak havoc in prisons. Prison evacuations have been haphazard and inconsistent, even as hurricanes continue to barrel toward the Gulf South every summer. When prison officials fail to evacuate incarcerated people, floods and power outages endanger thousands of lives.

When the mayor of New Orleans issued a mandatory evacuation of all residents on August 28, 2005, as Hurricane Katrina approached, the city’s sheriff publicly announced that there would be no evacuation of the 8,000 people locked in Orleans Parish Prison. Instead, many incarcerated people were left in their cells for days without power, food or water, while guards evacuated en masse. Many people’s cells were flooded with chest-high wastewater and others experienced wanton violence amid the unfolding crisis. All told, 517 incarcerated people remained unaccounted for during the Katrina evacuation.

Similarly, Texas prisoners were not evacuated in 2008 during Hurricane Ike, in what the Texas Civil Rights Project called a decision that “caused immense human suffering” for the weeks following the storm.

Fight Toxic Prisons, a grassroots advocacy organization, has been tracking extreme weather events and advocating for incarcerated people affected by them. Over the past five years, the group has been successful in improving the rate and response time of evacuation of prisons, and brought on other organizations to advocate for prison evacuations and releases in the face of climate-induced disasters. As Brooke Terpstra, an organizer with Oakland Abolition and Solidarity, explained to Truthout, “Floods have been a recurrent issue for prisons largely because of their decrepit buildings and marginal land, and we are now seeing floods in prisons because they are located on marginal land at the frontlines of climate disasters.”

The incoming floods are on track to cause a humanitarian disaster in any number of prisons throughout the Central Valley, particularly the Corcoran prisons which are at risk in the coming days and weeks. The only way to ensure the safety of incarcerated people is to evacuate these prisons for the upcoming flood season, close them permanently, and divert state investments to building strong, climate-resilient communities in California.

We have 10 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.