In the U.S., one election season begins pretty much as soon as the vote has been counted on the previous one. From one election to the next, tens of billions of dollars are spent — on ads, on lobbying efforts, on attempts to buy influence and to secure primary and then general election votes. In the U.K., by contrast, elections are a brief — and relatively inexpensive — affair.

There are no fixed dates in the U.K. national election schedule, only a requirement that a general election for members of Parliament be held at least once every five years. Boris Johnson called a snap contest at the end of 2019, shortly after becoming prime minister (PM), meaning a new vote had to be called by year’s end.

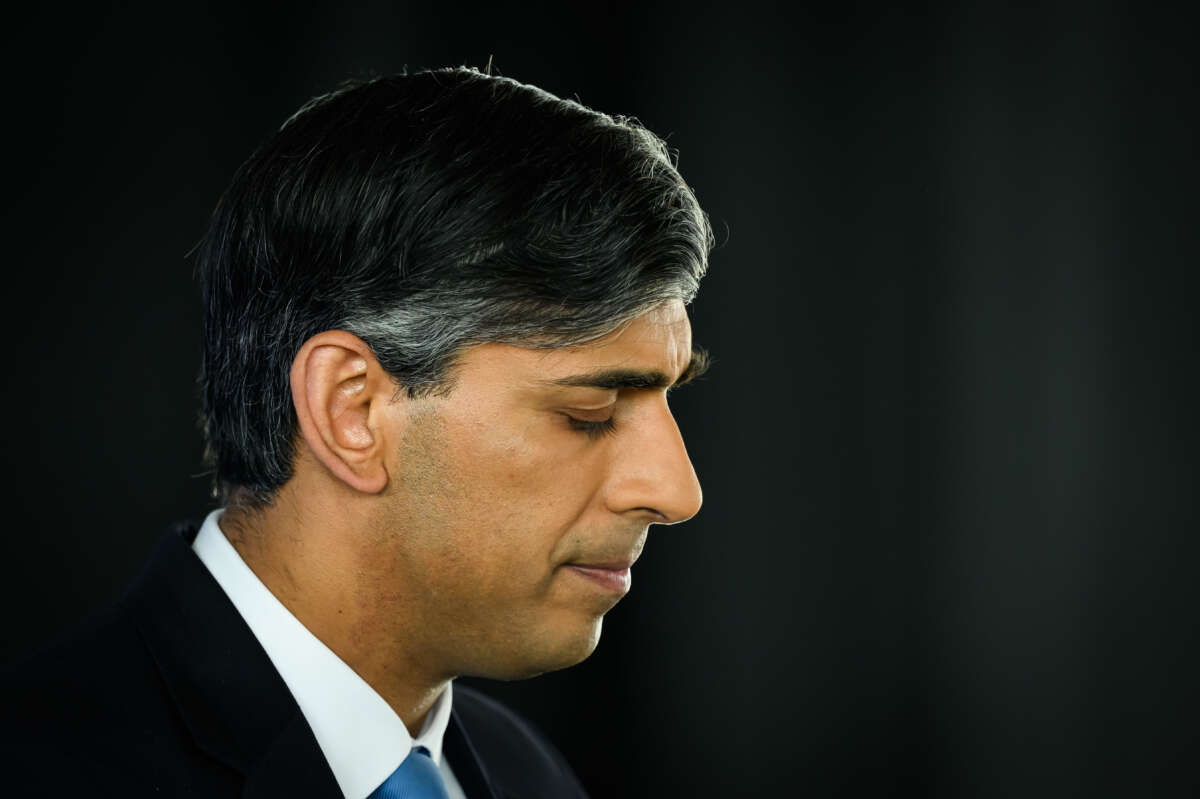

Since it takes a brave PM to call for an election right in the middle of holiday season, and to fill the airwaves with political ads instead of feel-good movies as Christmas nears, the bets had been that Prime Minister Rishi Sunak would call for an election in the autumn. Instead, facing stubbornly dismal polls that showed absolutely no sign of improvement, he announced that there would be a vote on July 4. The Labour Party, led by Sir Keir Starmer, has outpolled the Conservatives by upwards of 20 percent for over a year now, though a few recent outlier polls have shown a 12 or 14 percent lead instead. Meanwhile, the Conservatives have a growing tranche of members of Parliament (MPs) who very publicly declared that they would not seek reelection. Perhaps Sunak realized the game was up, and felt that calling an early election was something equivalent to a mercy killing.

Like so much else of Sunak’s tenure, there was something peculiarly hapless about the announcement. The prime minister, who has made the deportation of asylum-seekers to Rwanda — a punitive policy championed by his two immediate predecessors — a core part of his policy slate, stood outside of Downing Street, looking and sounding far more like a high school debater than the leader of a nuclear-armed country with the world’s fifth-largest economy. As he spoke, it started to rain — as it is wont to do in England. Somehow, his advisers had neglected to provide him with an umbrella or an awning, or to volunteer an aide who might hold said (absent) umbrella. They had also apparently failed to check out the sound system properly, so that the supposedly upbeat music that was blared forth to accompany the PM’s words ended up at least partially drowning them out.

A few days later, as part of a campaign swing through Northern Ireland, Sunak visited the shipyard that had, more than a century ago, built the Titanic. It wasn’t the best of media-ops. At one point, someone asked him what it was like to be the head of a sinking ship — and the taunts only got worse from there. Where, in normal years, the U.K.’s conservative tabloid newspapers could be relied upon to rally around the Tory leader, nowadays the notoriously bloodthirsty tabloid press seems to relish moments such as this, piling onto the inept leader at every opportunity. While some, like the Daily Mail, have (begrudgingly) endorsed the Conservatives, speculation is rampant that Rupert Murdoch’s papers will side with Labour — as they did to devastating effect in 1997, helping to usher in Tony Blair’s premiership. That speculation has only gotten louder since Sunak’s decision last week, critiqued by many even from within his own party, to return early from the D-Day commemorations in order to do a television interview.

Sunak is the latest in a string of five Conservative prime ministers — including his predecessors, David Cameron, Theresa May, Boris Johnson and Liz Truss — who have cumulatively driven the U.K. into a seemingly endless series of crises.

To lance the boil of internal Conservative Party fighting over Britain’s role in the European Union (EU), Cameron made the entirely disastrous decision to allow a referendum on continued membership, and then ran an entirely disastrous campaign to keep Britain in the EU that foundered in the face of Boris Johnson’s faux-populist opposition. Every leader in the eight years since that vote has been consumed by its consequences — by disentangling the country from a half-century of regulatory and legal involvement with the EU and its predecessor, the European Economic Community; by managing the economic and demographic dislocation of the ending of reciprocal rights to live, study and work in any of the 27 member nations of the EU; and by trying to sufficiently staff the chronically underfunded National Health Service (NHS) now that the EU’s medical workers are no longer granted automatic right of entry.

Theresa May managed to push off most of the consequential decisions around Brexit for a few years, but she then ended up falling to the schemes of the ever-ambitious Johnson who maneuvered her out of office in the summer of 2019. A few months later, Johnson’s strategy appeared vindicated when he called a snap election, focused mainly on “getting the job done” and finishing Brexit, and — faced with a Labour Party bitterly divided by the rise of its left-wing leader Jeremy Corbyn — broke Labour’s so-called red wall in northern England and won a huge election victory. There was talk of permanent Conservative Party rule and of a newly populist politics that would essentially Trumpify the U.K., albeit with a smattering of Latin and Greek classical phrasing — witness Johnson’s lapse into Ancient Greek during an address to the United Nations in 2019, or his quoting of the Roman Emperor Augustus — thrown in for sophisticated good measure.

But Johnson’s power was illusory. In the end, he was undone by a series of COVID-related scandals and a growing sense that his was a lawless and — perhaps the bigger folly — an incompetent leadership. When Johnson fell to Earth, Liz Truss picked up the baton, being asked by Queen Elizabeth to form a government in what turned out to be the ailing 96-year-old monarch’s final public act (humorists promptly declared that offering Truss the keys to Downing Street was so unpleasant that it helped Elizabeth shuffle off the mortal coil). Her efforts to radically shake up the economy were stunningly mismanaged, triggering a run on the currency, a hike in interest rates and the very real possibility of a general economic collapse. Soon afterwards, her party turned on her, forcing her to resign.

All told, Truss lasted seven weeks, a shorter term in office than any other prime minister in British history.

Sunak is the heir of all of this incompetence and hubris, the arrogance of a governing class that has so badly lost its way that fewer than one in four voters say they are likely to support Conservative Party candidates in the general election. He came in promising to restore stability — the core currency of Conservative governance across the centuries — yet during his time in office, the economy has stagnated, inflation has remained high, NHS waiting lists for medical treatment and shortages of basic medicines have grown to catastrophic levels, the country has seen rolling strikes in sectors ranging from transport to teaching to medicine to border security, and the Rwanda deportation policy has been mired in a series of ongoing legal challenges.

Given all of this, the election is Labour’s to lose. The party, which hemorrhaged support during Corbyn’s leadership, and which was seen by many voters to represent a nonviable throwback to the ideological strife of the 1970s and 1980s, has recalibrated over the past five years. Under Starmer’s leadership, it has kicked out many of its more left-wing members and senior figures — including Corbyn himself, who is now running for his parliamentary seat as an independent, removed from the party after investigations found him to have facilitated antisemitism in the party — as part of what critics have termed a “purging” of left-wing viewpoints. As the election campaign has gotten underway, it has also removed several locally selected parliamentary candidates, including Faiza Shaheen in Chingford — an East London seat that used to be a Thatcherite redoubt — whose “crime” was apparently a series of tweets, authored years earlier, amongst which she accused the party of tolerating Islamophobia in its ranks.

In place of ideological commitments to renationalize large parts of the economy and to aggressively redistribute wealth, Starmer’s team has promised only moderation — not to spend outside of its means; not to, in any way, shape or form, promise more than it thinks it can deliver. It hasn’t made bold pledges on reworking the current antagonistic relationship with the EU, and it hasn’t pledged huge Green New Deal-type economic commitments. The fewer hostages to fortune the party puts out, Starmer believes, the better its chances of securing a huge parliamentary majority come July.

None of this is particularly inspiring, but at the moment it is doing the political trick. The rolling average of polls tracked by the BBC shows Labour with a seemingly impregnable lead. Some polls have suggested that the Conservatives face an electoral wipeout that would leave it with only a few seats in Parliament. And, since the U.K. electoral system is first-past-the-post, the other parties — the various nationalist parties, the Greens, the Liberal Democrats, the xenophobic Reform Party, and a smattering more — will find only slender pickings in terms of parliamentary seats gained. In consequence, if the Conservatives implode in the way the polls suggest is likely, Labour will end up with a huge parliamentary mandate.

As the election campaign has intensified, Sunak has unveiled a few big policy pledges — including a surprise initiative to reintroduce compulsory military or community service for 18-year-olds. He has tacked to the populist right on environmental issues, has doubled down on the cruel — and vastly expensive — policy of deporting asylum seekers to Rwanda, and has used the power of the purse to promise tax cuts to senior citizens.

Labour has hewed to its nonspecific platform, repeatedly promising “change,” without specifying exactly what that change would look like. Yes, the party will put the kibosh on plans to fly asylum seekers to Rwanda, but it hopes to woo those opposed to asylum by cutting 3 billion pounds in foreign aid funding that has been used to house asylum seekers in hotels. The party has ruled out a new freedom of movement agreement with the EU, and says that non-British residents with EU passports won’t be able to vote in U.K. elections. Both of these are policy U-turns from positions held in the years after the Brexit vote. It has announced modest plans to better fund the NHS and to cut wait times for appointments and surgeries, and it has come out in support of a mildly increased minimum wage.

These are, however, all technocratic tweaks to a wildly out-of-whack system. There’s no grand vision for change in the party’s manifesto, no sense of alternative possibilities and the potential for a seismic shift in what the social compact looks like after the election.

Labour looks likely to win a thumping majority come July 4. The question is, what will it do with all that newfound power?

Urgent message, before you scroll away

You may not know that Truthout’s journalism is funded overwhelmingly by individual supporters. Readers just like you ensure that unique stories like the one above make it to print – all from an uncompromised, independent perspective.

At this very moment, we’re conducting a fundraiser with a goal to raise $21,000 before midnight tonight. So, if you’ve found value in what you read today, please consider a tax-deductible donation in any size to ensure this work continues. We thank you kindly for your support.