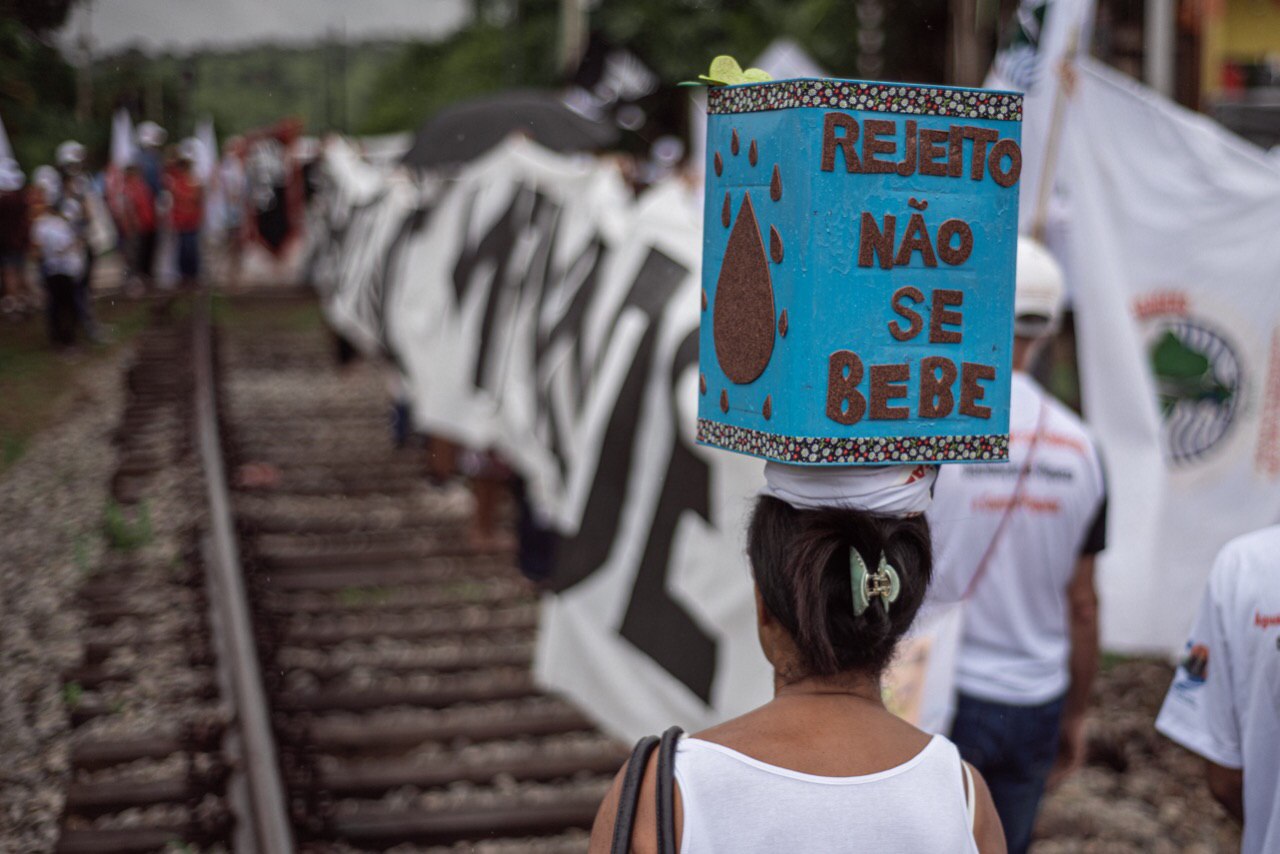

On January 20, about 350 people gathered together in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, to begin a five-day march to commemorate the one-year anniversary of a deadly dam collapse that occurred at Córrego do Feijão in Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, Brazil, on January 25, 2019. “Vale Destroys, The People Build!” declared participants with the Brazilian Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB, or Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens in Portuguese).

MAB is comprised of communities directly affected by dam projects, and fights against the privatization of water, rivers, natural resources and the displacement of communities. Between January 20 and 25, 2020, MAB coordinated an agenda to draw attention to what happened a year ago and to call for Vale, the Brazilian multinational mining corporation responsible for the collapse, to be held accountable. Individuals from 17 countries across Latin America, Europe and North America participated.

As a result of the dam collapse, more than 250 were killed and 11 are still missing, with billions of gallons of toxic sludge still devastating communities there. Brazilian news outlet Brasil de Fato called the collapse “the biggest man-made social and environmental disaster in Brazil’s history.”

Beginning with a march and demonstrations in the city of Belo Horizonte on January 20, and then journeying through three of the cities most impacted by the collapse — Pompéu, Juatuba and Betim/Citrolândia — participants drew attention to the continuing struggle of those affected, and denounced Vale’s water contamination and its impact on the health of communities.

On January 24, participants gathered for an international seminar organized by MAB titled: “Profit Does Not Value Life! One Year of Vale’s Crime in Brumadinho.” The seminar was held in Citrolândia, Betim, and included the directly affected as well as the National Confederation of Bishops of Brazil; the Movimiento de Afectados por Represas en Latinoamérica (Movement of People Affected by Dams in Latin America); representatives from national authorities (including a representative from the Chamber of Deputies, similar to the U.S. House of Representatives); and international delegates from 17 countries.

During the seminar, the directly impacted present were asked to stand, as were the people from the international delegation, most of whom have also been affected by dam projects in their respective countries. There was a minute of silence for those killed in the dam collapse, and the room was filled with emotion, with many people visibly crying.

Famed theologian Leonardo Boff spoke. What happened in Brumadinho, he said, was not a natural disaster or accident, but rather a crime. He called the struggle against Vale a “global fight against an energy model that is anti-life,” and blamed what he called a cruel global economic system that allows people to be “buried alive in mud, just so that a few people can make money.” He also underscored the urgency of the global climate crisis, calling for the decommodification of natural resources like water.

The march ended on January 25 at Córrego do Feijão in Brumadinho, the site of Vale’s dam collapse a year ago. As yellow and white balloons were released into the air in memory of each life taken, I thought about how this beautiful town has been filled with death — death of its river, fish and people. The point was to honor victims, to bring attention to their lives and to remember that their deaths came at the hands of Vale’s criminal activity.

Afterward, mourners walked a short distance to lay roses in memory of the victims at the entrance to the dam breach, which was surrounded by polícia militar — the military police, which are one of several branches of police in Brazil. (The military police are also a part of the Brazilian Army, and may also act as a reserve force.) At least 10 military police escorted buses carrying MAB and solidarity partners to Brumadinho on January 25. Many more met us once we reached Brumadinho. Under the administration of right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro, Brazilian social movements like MAB fighting for Indigenous people, Black people, peasants and rural workers have faced increased criminalization. In 2018 alone, for instance, 5,000 were people killed by police. In addition to combating this increased criminalization, MAB is also faced with challenging existing discourses on the socio-environmental sustainability of dams.

“Water for Life, Not for Death”

This phrase is used by MAB to draw attention to the fact that water is necessary for life to exist, but the current energy model in Brazil (and the world) is anti-life — for people and for nature. Many people assume that in the face of climate change, dams must be built because hydropower is a better, “cleaner” source of energy than fossil fuels. This is a misconception. In fact, dam reservoirs are a significant source of methane emissions, a greenhouse gas, while free-flowing rivers actually trap carbon. The Balbina Dam in Brazil, for example, is 10 times dirtier than a coal-fired power plant that generates the same amount of energy.

Dams also disturb ecosystems by restricting water from flowing where it naturally would go, and flooding habitats to create the reservoir. This creates a situation where it is harder to adapt to climate change — especially as we continue to see more unpredictable weather patterns and more flooding. Moreover, the energy generated by dams in Brazil does not actually find its way to peoples’ homes; it instead serves large industry and mining operations, lining the pockets of large multinational industries.

Vale owns a total of 175 dams in Brazil. According to MAB, 129 of these are iron ore dams, of which 102 are in Minas Gerais — the Brazilian state in which Brumadinho resides. According to Vale, 270 people (including two pregnant people) were killed in the Brumadinho dam collapse, 11 of whom have not been found. Of the total killed, 250 were Vale workers, representing 40 percent of its workforce in the area. As such, the tragedy also represents a labor rights violation.

In February 2019, Vale agreed to pay up to the minimum wage ($3,227.02 per year) to each adult resident in Brumadinho. The company announced in November, however, that it will halve its payments to approximately 95,000 residents who live in the 48 cities impacted by dam collapse’s toxic sludge. The decision was reached without the participation of directly impacted communities, and MAB is challenging this decision.

Moreover, while Vale will continue to pay the full wage amount to approximately 15,000 people who live in the six communities most impacted by the disaster, at least 12,000 people affected by the collapse are not receiving any kind of aid. As Brasil de Fato reports, the company is continuing to withhold aid to those who cannot prove they live in the affected areas.

This speaks to a larger, historical process of colonialism, exploitation and erasure of Ribeirinho (riverine) communities, whose residences are often not registered with the state. In theory, these communities are considered to be a “traditional” population that receives protection; in practice, however, they rarely receive legal recognition. But it’s these communities that are most in need, since they cannot grow food or drink water from the Paraopeba River, now contaminated with iron, aluminum and mercury. The Ribeirinho have since been displaced, and continue to face illnesses including rising rates of mental illness and suicide.

What happened in Brumadinho was a crime, and people everywhere need to be aware of it and work to ensure that Vale is held accountable. More than 45 percent of Vale’s shareholders are international, including some of the world’s largest investment management companies based in the United States. BlackRock and Capital Group each hold about a 5 percent share in Vale. Meanwhile, BlackRock and Vanguard Group, another company that holds shares in Vale, both claim their operations are environmentally responsible.

With trillions of dollars each, the amount of money managed by these companies is hard to conceive. Vale itself is accruing more profit each year, even as this accumulation comes at the expense of people and of the environment.

To date, no Vale representatives have been held to account, although on January 11, Vale corporate heads — including the company’s former CEO along with five other officials from a Germany company who certified the dam was safe — have been charged with aggravated first-degree murder. Vale is contesting the charge. A year delayed, the charge still comes as good news to many who argue that the company knew a dam breach was possible and did nothing to prevent it.

In a statement issued on January 25, MAB demanded “full reparation for the survivors, family members and all those affected who had their lives transformed, reflecting the mining company’s negligence and greed.” The demand shows why people from around the world are standing together with MAB — because, as the group states, “only the organization of the people can change this reality. We, affected by dams, know that it is not possible to expect goodwill from governments or from Vale.”

We have a choice to make. We can follow in the direction of the international solidarity expressed during MAB’s five days of commemoration and listen to the global communities demanding that life must come before profit, and point the way to building a better world; or, as theologian Boff notes, we can head toward ecological and social collapse. We need three things to change our course, Boff says: hope, indignation and courage.