Part of the Series

Progressive Picks

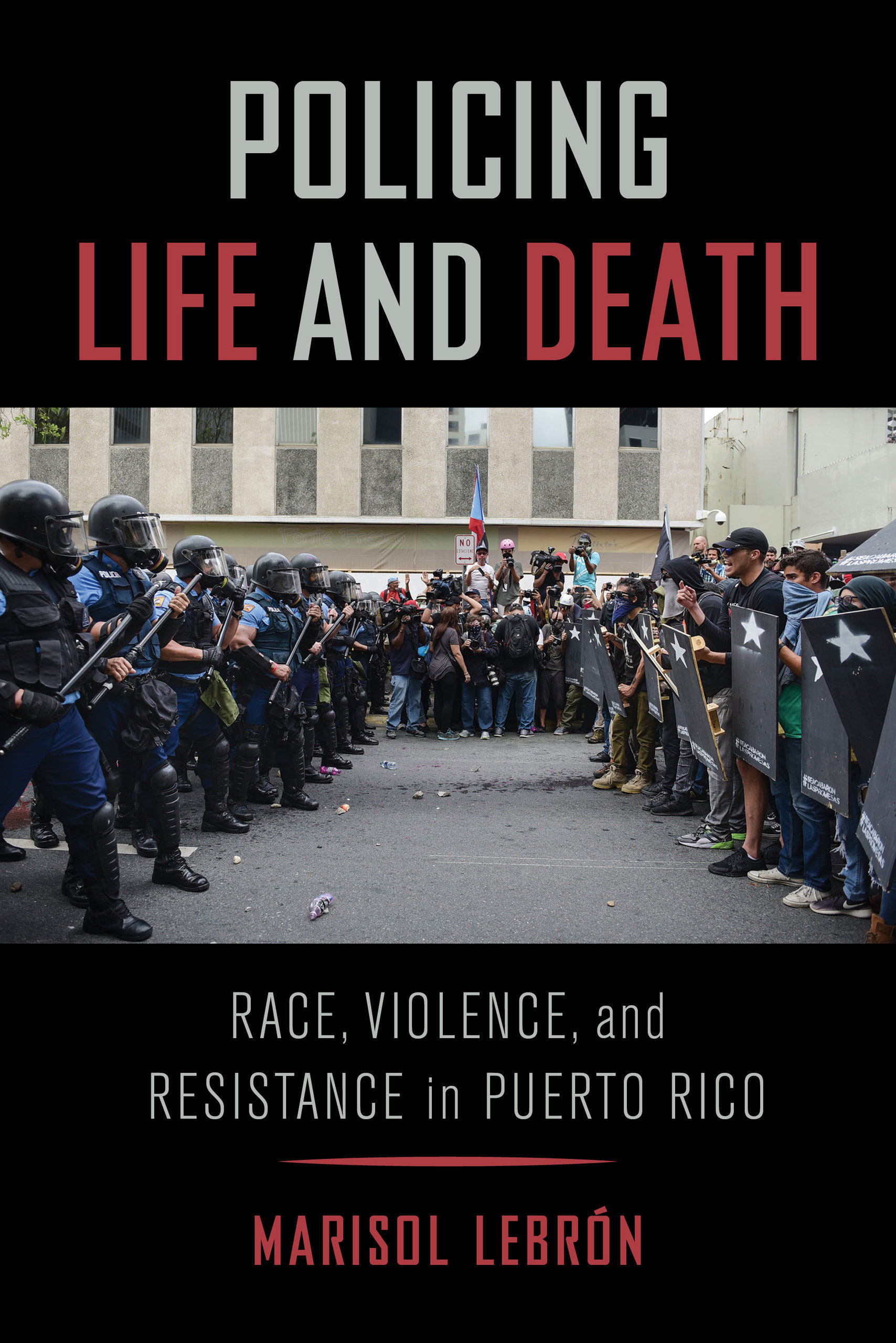

In Policing Life and Death: Race, Violence, and Resistance in Puerto Rico, author Marisol LeBrón shows how Puerto Rico’s colonial relationship with the U.S. has shaped policing in the archipelago as a form of “colonial crisis management.” Her new book exposes the ways policing harms marginalized communities and deepens social inequality. In this interview, LeBrón discusses the legacy of punitive “solutions” and the various ways Puerto Ricans are challenging state violence and building alternative forms of justice.

Truthout: Policing Life and Death begins with the history of a series of anti-crime measures introduced in Puerto Rico in 1993 called mano dura contra el crimen. What exactly was mano dura and why is it central to understanding the legacy of policing in Puerto Rico?

Marisol LeBrón: Mano dura contra el crimen, which translates to “iron fist against crime,” was a series of crime-reduction measures introduced by Puerto Rican Gov. Pedro Rosselló in 1993. As part of mano dura, police and military forces raided and occupied public housing and other low-income spaces around the archipelago, but primarily across the big island, in an effort to eliminate drug trafficking. The activation of the Puerto Rican National Guard as part of mano dura’s “war against crime” remains one of the longest “peacetime” mobilizations of a National Guard unit under U.S. jurisdiction. The willingness of the Puerto Rican government to unleash military tactics and technology against public housing and barrio residents really showed the extent to which some of Puerto Rico’s most vulnerable citizens had been marked as internal enemies of the state.

Although mano dura was short-lived, in the book I show how it’s fundamentally reshaped not only what policing looks like in Puerto Rico, but also how people understand and experience life and death. Mano dura succeeded in playing upon existing hierarchies within Puerto Rican society to strengthen connections between Blackness, poverty and crime, which justified and normalized state violence in the name of public safety. Although politicians have attempted to distance themselves from the punitive violence of mano dura contra el crimen, it has really become the blueprint for how to deal with feelings of rising social insecurity. Whenever people feel like crime is “out of control,” the answer is always the same: Put more police on the streets, especially in public housing. Data show, however, that this strategy has been largely ineffective in actually reducing crime and violence in Puerto Rico, but it’s still the go-to answer for the government.

You argue that policing in Puerto Rico is a form of “colonial crisis management.” Can you explain how the archipelago’s relationship with the U.S. shapes what you describe as “punitive policing”?

Although we use the euphemism of Commonwealth, the reality is that Puerto Rico remains a colonial possession of the United States. This has been made painfully clear for many in the aftermath of Hurricane María, when people saw just how little power Puerto Ricans have in the running of the country. We have to situate the growth of punitive governance within the ongoing colonization of Puerto Rico by the United States. Policing became an important tool for the state as it tried to manage a range of social, economic and political crises stemming from the Puerto Rico’s continued incorporation into the United States. Colonial rule prevents radical transformations within the official political or economic realms. As a result, the Puerto Rican state turned to punitive governance in order to manage how colonial crisis was felt at the population level and promote the image of a strong and active state. This isn’t to say that if Puerto Rico wasn’t a colony that it wouldn’t have gone down a punitive path, but it is to say that that the colonial relationship with the U.S. shaped how and why Puerto Rico reached for punitive solutions to its problems.

Another central argument in your book is that policing has deepened social inequality and made marginalized people even more vulnerable. What are some ways this has happened?

Punitive governance works to contain the effects of a social order that is marked by extreme racial and economic inequality. The more unequal a society, the more likely we are to see forms of hyper-policing and incarceration. In an effort to manage this unequal social order, policing often targets those who are already vulnerable within the existing social order – those who are most likely to feel the effects of this unequal system.

In this way, policing in Puerto Rico reproduces hierarchies based on race, class, spatial location, gender, sexuality and citizenship. Policing is part of what makes these differences real in many people’s minds. I argue in the book that the turn to ever more punitive strategies of policing in Puerto Rico has resulted in the exposure of economically and racially marginalized communities to greater harm at the hands of the state and their fellow citizens. It does this in ways that are overt, like creating a culture of impunity that fosters police brutality and extrajudicial killings, and in ways that are more subtle, like creating the expectation that drug dealers killed by police or rivals are getting what they deserve given their chosen career path. As a whole, this punitive system justifies its own actions and existence by normalizing the violence of the state and normalizing forms of harm that vulnerable people are routinely exposed to.

What are some ways Puerto Ricans are organizing outside of the state to seek justice and challenge state violence?

Puerto Ricans have always pushed against the implementation of punitive and repressive state policies. From the moment mano dura contral el crimen was implemented in 1993, Puerto Ricans, especially those in public housing, challenged the government’s justifications for the discriminatory and violent policing that they experienced. Resistance could look like anything from refusing to collaborate with police efforts, to organizing protests or speaking out in the press. In the book, I document a lot of creative examples of people pushing against the punitive logics of the state. For instance, we see underground rap music emerge as a venue where young people talked about police harassment and called out the hypocrisy and failures of the war on drugs in Puerto Rico. Social media is also an important space for conversations to take place around ideas of violence and the responsibility of the state to protect all and not just some of its citizens.

As a growing number of Puerto Ricans feel that mano dura-style approaches cause more problems than they purport to solve, we’ve seen people experiment with implementing non-punitive solutions to social crisis and insecurity. One of the most incredible examples of this that I document in the book is Taller Salud’s Acuerdo de Paz program. Taller Salud is a feminist public health organization that has primarily been concerned with women’s reproductive health issues, but in recent years, they’ve also worked to address the physical and psychological harm of gang violence in their community. When the community of Loíza was dealing with surge in gang violence, they proposed an alternative model for dealing with violence that decentered the role of the police in providing public safety. This was important because, as a town and municipality with a large Black and low-income population, Loíza has been a site of tremendous police repression and brutality. Acuerdo de Paz employed community members with high levels of community “credibility” to work with individuals at risk of experiencing or enacting violence. They worked with individuals, usually young men involved with neighborhood gangs, to mediate situations that have the potential to end in violence and to de-normalize violence as a solution to conflict. They even worked with the young men to think about how narrow ideas about power and masculinity were contributing to community violence. The program showed great results – during Acuerdo de Paz’s three-year pilot program, Loíza saw a marked decrease in rates of violence. Acuerdo de Paz’s success shows what can happen when we funnel resources into communities and allow them to work toward their own vision of a strong and safe community.

Have Puerto Ricans experienced a deepening of punitive responses in the aftermath of Hurricane María?

The successive gut punches of the debt crisis and Hurricane María, which are, in many ways, related to one another, have caused massive social upheaval in Puerto Rico. The local and federal governments have responded to people’s feelings of fear, abandonment, and insecurity with repression and punitive solutions. When the debt crisis worsened and the PROMESA Act was implemented, people was understandably furious when it was announced that an unelected financial control board would be overseeing Puerto Rico’s finances and, in effect, making decisions about people’s futures. La junta, as locals call the board, is widely regarded as an undemocratic and colonial imposition that has Wall Street as opposed to the Puerto Rican people’s best interests at heart. People took to the streets to protest PROMESA and la junta, and the local and federal governments responded in a really repressive manner. For instance, there’s the famous case of Nina Droz, who is in federal custody for allegedly trying to set fire to a Banco Popular office located in Puerto Rico’s “Golden Mile” during a May Day protest. Droz was portrayed as a terrorist and used as an example to discipline other anti-austerity protesters. More recently, we’ve seen the case of Elimar Chardón Sierra, a music teacher who faced federal charges because she said in a Facebook post that she hoped that Laura Taylor Swain, the judge overseeing Puerto Rico’s debt restructuring case, died. What we’re seeing is that protest, rage and frustration at the situation in Puerto Rico is increasingly criminalized by both the local and federal governments.

Post-María, there has been an increase in concern over rates of violence among many different segments of the population, but the state continues to fall back on punitive policing solutions that don’t work. A couple of months after the storm, for instance, the Puerto Rico Department of Public Safety announced that they would be pursuing a strategy of broken windows policing in an effort to cut down on homicides. Puerto Rico has essentially been practicing broken windows policing on and off for the past 20 years and it has not proven effective in reducing crime or violence. To the contrary, it usually ends up causing greater violence as police come into more frequent contact with civilians, which can lead to violent confrontations. Activists organizing on the ground work toward police accountability and push for non-punitive solutions to social crises.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.