Since election night 2016, the streets of the US have rung with resistance. People all over the country have woken up with the conviction that they must do something to fight inequality in all its forms. But many are wondering what it is they can do. In this ongoing “Interviews for Resistance” series, experienced organizers, troublemakers and thinkers share their insights on what works, what doesn’t, what has changed, and what is still the same. Today’s interview is the twelfth in the series. Click here for the most recent interview before this one.

Last week, on February 8, Guadalupe Garcia de Rayos went to her yearly check-in with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in Phoenix, Arizona, something she has done every year since 2008, when she was arrested in a raid by notorious Sheriff Joe Arpaio and convicted of using a fake Social Security number to work (and pay Social Security taxes that she would never be able to collect). This time, instead of being sent home to her family, she was loaded into a van and deported to Mexico, despite a group of her friends and family and supporters placing their bodies in the way of the van. Her 14-year-old daughter had to pack her things for her; she, along with her brother and father, would be staying behind.

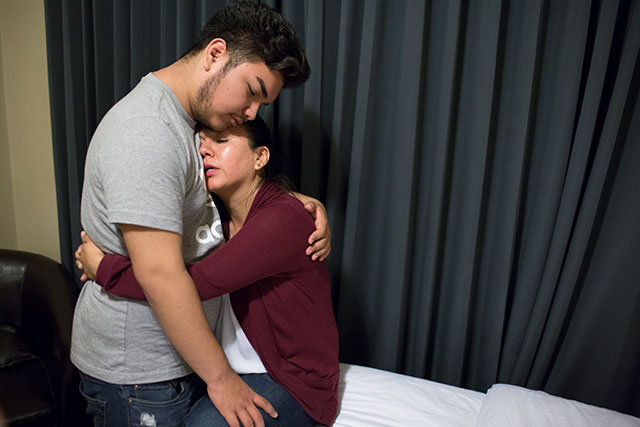

Maria Castro — a community organizer for People United for Justice and a member of Puente Arizona — was one of the people putting her body on the line to try to prevent Garcia de Rayos’s deportation. We asked her to talk about what will be necessary to prevent more families like Garcia de Rayos’s from being split up.

Sarah Jaffe: Tell us about the action you were involved in in Phoenix.

Maria Castro: Lupita Garcia de Rayos was a victim of Arpaio’s illegal raids in 2008. Every year, Lupita has gone in to check in with ICE and [every year] they have granted her permission to stay in the country one additional year. Every year it was the same, except for this year. This year we had Lupita walk in with the priest from her congregation and an attorney. This time she was put into removal proceedings, meaning deportation.

I think we sugar-coat it by making it very procedural, but actually, that night she was kidnapped from her family, and there are many of us in the community that took action. We had them waiting outside in vigil for Lupita in hopes that the director would have released her. Unfortunately, because of Trump’s new executive orders she, much like 8 million other people, [is] now high priority for deportation. I was standing on the sidewalk and we started to see vans leaving.

This is not the first time that we as community activists in Arizona have done this kind of work. A couple of years ago, in August 2013 I was sitting in front of a bus. Then, a few months later, in a different facility, we chased down a bus and the person who we were fighting for was snuck out in a van. Learning from these things, we knew that they had a bus at the front of the facilities and we knew that [it] was a decoy. So, we chased the vans. Myself and about half a dozen people jumped in front and were being pushed. The van literally pushed me at least 30 feet, hyperextending my knees, hurting some of my friends, knocking some of my fellow organizers down to the ground. It wasn’t until we had one of the vehicles in front of the vans and then, another person started to hug the wheels and put his own life at risk, because this is just the beginning. This is the beginning of the militarized removal of our communities, of our families, and of our loved ones. The people in these vans who were driving them were very highly equipped with weapons.

You have been building a network to do things like this for a while. Can you tell us a little about the work you have been doing?

On January 20 everyone woke up in Arizona. We have been living with a legislature that is constantly defunding education and prioritizing its residents for deportation. We live in a city, in a state and in a county where the sheriff did as he pleased and dismissed the federal government, dismissed the Constitution, dismissed our basic human rights.

Once we heard that Trump was elected, it was a bittersweet moment because that night we had also defeated one of the biggest villains that we have seen, the Bull Connor of our time, [Maricopa County Sheriff Joe] Arpaio. We had to celebrate that, but at the same time, we began to prepare. As many organizers did during the reign of Arpaio, people have been starting to form what we call Defense Committees all across the state. As organizers here in Arizona and across the nation, we have developed different tactics in order to fight the deportation machine — through national organizing or local organizing, contacting our senators, whatever it may be. We have been able to delay or stop some people’s deportation by intervening in different phases.

Right now our priority has been to decrease the amount of initial contact that our people are having with law enforcement. Under [the Obama] administration we have had different tools at our fingertips. Right now, Trump has taken away our tools. Our people need to arm themselves as best as they can by knowing their rights, but having plans in case things go bad like it went with Lupita. They have to have these very difficult conversations. We are not just having these fire drills of deportation. We are having to plan and have difficult conversations, like with my mom. My mother is undocumented. I had to sit down and talk to her and say, “What do you want to do?” She and I are raising my younger sister together. We have to figure out what is going to happen. Are we going to have my little sister go to Mexico with my mom? Is my sister going to stay here with me? These are some of the conversations that we have to prepare for. Because as of right now, all we have is trying to protect each other from having that initial conversation with law enforcement.

In terms of these kinds of direct actions in resistance, obviously they are a worst-case scenario, but at the same time, you have had some success in the past with this, correct?

Yes. Like I said, we were equipped with different tools under a different administration. Not only are we under attack by [the Trump administration], but it is even more hurtful for us and our resistance to have weak politicians who give opportunistic speeches, confuse our community and simply (and quite frankly) do absolutely nothing. By doing nothing, they are empowering the Trump administration. They are enabling the deportation and the kidnapping of our family members and really making it difficult for us in our organizing, having to re-explain to folks, “Actually, your mayor doesn’t care. Actually, your mayor has been deporting you in mass amounts.”

Mayor Greg Stanton came out and said, “I will not allow the new administration in Washington, DC, to turn our police department into a mass deportation force,” but what he failed to mention was that the Phoenix Police Department is already a mass deportation force. One of the biggest deportation forces in the country. For us, it is a slap in the face, but it also means that we have to work harder. It also means that we have to work on educating our community. It needs to be replicated everywhere in the country. We need to make sure that we are forcing our elected officials to take big and bold stances because we are not in a time where speeches are going to be enough. We are constantly under attack and we need bold moves. That is what is required in order for us to survive this administration and our elected officials who are enabling the administration. We need them to declare sanctuary. We need them to change policies and make concrete and bold moves.

We also need our communities to come outside. I can’t stress that enough. I feel like we have gotten comfortable over the years with the organizing that we have done in the past. Sharing things on Facebook is good. It is important for us to help expand the visibility of our actions, but what is necessary is our feet on the ground and our feet to be marching and for us to be constantly resisting. I am not saying just for immigration. I think Mother Earth is under attack. If you feel passionate about working against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, if you are passionate about women’s rights, if you are passionate about LGBT rights, Muslim rights, the rights of the working class, whatever it may be, I think this is a moment where we need to pick ourselves up and choose where we are standing. We can’t sit down anymore.

In terms of specific things, you mentioned stopping the bus before. Can you talk about some of the past direct actions that you have done?

It is important to be grounded in community first and foremost. I think it is very easy to identify an action. Like one we did a couple of years ago: we jumped in front of a bus and made national news, but what is important is identifying the needs of our community. In this moment, our communities are being kidnapped out of their homes, out of workplaces, off the street, and we need to do whatever is necessary to protect them and make sure that we are being safe and bold and brave; and in some spaces, depending on the conditions, in some of the more liberal states, you may be able to do more and you should do more. That is what is required of us. In some places, it may look like sitting in front of a bus. In other places, it may look like locking down some facility. In other places, it might look like vigils and creating sanctuary spaces. It all depends on the setting, but what is vital and necessary is that you do something.

Since Trump’s election, we have seen massive protests. We have seen some four million people in the streets for the Women’s March. We saw people rushing to airports in response to the Muslim ban. How do people get connected to these networks? The airports, in particular, showed that people are willing to take some risks to defend people in their communities, even people that they don’t know. What is some advice that you have for building these networks, and for introducing people who maybe went to their first protest at the Women’s March to what they can do in their communities to defend people who are facing deportation?

There are organizations in your community. The thing is that you have to identify them. If you are in a small town and you recognize that actually there isn’t an organization, then it is important that you start one and that you get in communication with other organizations across your state and across the country. I think that with the new attacks on our community, they have shifted the status quo. Then, it is our move and we are the ones who have to disrupt business as usual. We are the ones who have [to stop] them from carrying out the atrocities that [the] administration is trying to do.

Whatever organization you are joining, whatever protest you are joining, whatever organization you are creating, you must do everything in your power to [throw a wrench] in the system, because the system is not working for us. It is working against us. Marching in the streets is powerful when you are doing it in masses. If you feel that you cannot bring thousands of people out, then do something else. Talk to your legislator. Go making sure that everybody is divesting from a specific bank. Whatever target you choose, make sure that you are doing it coordinated with national organizations.

It is key for us to identify something that we are passionate about, because this is a long fight. It doesn’t end with Trump and it didn’t start with Trump. The Obama administration deported close to three million people. Trump is just one-upping him. He is continuing to use the tools that Obama and Bush and Clinton laid out for him. It didn’t start on Election Day. It didn’t start on Inauguration Day. But, if it started for you that day, then you need to continue and be ready for the long haul.

Since you were living under the reign of Joe Arpaio, talk a little bit about his defeat this year and what that says for the changing politics in places like Arizona.

The fight against Arpaio has been a very long one and one in which we have lost an incredible amount of members of our community. It is a fight that has been carried out with multiple angles and different methods of resistance. There have been mass protests with hundreds of people flooding the street. There have been lawsuits that have been filed. There have been divestment campaigns. There have been arrests and civil disobediences. After 10 long years of resistance, we were able to develop a hybrid campaign in which we highlighted the atrocities that he was bringing into our communities, but we were also highlighting the strength and the power in our community. It was both an electoral and a direct action campaign called Bazta Arpaio.

During this campaign, we were feeling the energy of the community. At this point, after 10 years of mobilizing and organizing, it wasn’t just us, the community organizers and membership, it was the entire county resisting Arpaio, lifting up their businesses, lifting up their community organizations, and together walking out of school, everything. We were very happy to see Arpaio go. We want to make it clear to the new sheriff, Paul Penzone, that he did not win the election — we defeated Arpaio.

Lastly, how can people keep up with you and the work that you are doing in Arizona, and what are some national networks that people could get plugged into that might help them find work that they can do in their communities?

I am currently organizing with People United for Justice. It is an organization that is bringing together people who are vulnerable, particularly under this administration, and resisting through electoral campaigns and working on the state legislature. Like I said, people woke up in Arizona, but we still live in Arizona. We have our difficult politics in the state legislature. Before Trump came out strong against sanctuaries, the Arizona State Legislature had already made moves to outlaw sanctuary cities. We are not only under attack by the Trump administration, we are not only under attack by Congress, we are not only under attack by our governor but also our state legislature; and the inaction of our city council and mayor have made it even more difficult for us. You can definitely follow us on Facebook, as well as [the] Puente movement, which is working on the Defense Committees all across the state, in order for us to be able to amplify the support that we can create and amplify the resistance that is necessary under this administration and under that state government.

Nationally, there is an organization and a network called Mijente and they are doing a lot of great work. There is also Cosecha, an organization that is working on the general strike. Then, there is United We Dream, an organization that works primarily with migrants all across the nation. They have chapters in almost every state.

Interviews for Resistance is a project of Sarah Jaffe, with assistance from Laura Feuillebois and support from the Nation Institute. It is also available as a podcast. Not to be reprinted without permission.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.