The appointment of retired Army General Mark S. Inch to head the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) is a major blow to those working for prison reform under Trump. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced on August 1, 2017 that Inch would be taking over the position. In the past, Inch has been responsible for detainee operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, which have been plagued by accusations of torture and abuse. Looking at Inch’s record, many prison activists and formerly incarcerated people expressed alarm that his appointment will likely lead to worsening conditions in the future.

This news comes just days after Trump gave a speech before police in Long Island, New York, joking that they should treat suspects “rough” and not be “too nice” to those he called “thugs” and “animals.” Throughout his campaign for president, Trump billed himself as the “law and order” candidate — rhetoric that apparently resonated with his base.

Attorney General Sessions, appointed by Trump, has expressed his own support for the war on drugs, asset forfeiture and anti-immigration policies. In his announcement, Sessions called Inch a “military policeman” who was “uniquely qualified” to head the federal prison system.

Truthout spoke with Amy Ralston Povah, who served nine years in federal prison before being granted clemency by President Bill Clinton. After her release, she founded CAN-DO to secure executive clemency for those convicted of drug offenses in federal prisons. She said that Inch’s appointment signals the further “militarization of the Bureau of Prisons.” US citizens, she said, are viewed by prison authorities as “combatants” who have no rights to defend themselves.

Give Him an Inch

Since his inauguration, President Trump has appointed several retired generals to prominent positions typically held by civilians. Trump’s transition team included three of them in his cabinet: Gen. James Mattis as Secretary of Defense, Gen. John Kelly as Secretary of Homeland Security, and Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn as national security adviser. Mark Inch retired from the military in May 2017, after serving since the early 1980s in the Army’s military police. He takes the place of Thomas R. Kane who had worked at the BOP since 1977.

Early in his career, Inch worked at the Army’s Ft. Leavenworth prison. From 2008-2009, he was chief of staff for Task Force 134, overseeing detention facilities in Baghdad during “Operation Iraqi Freedom.” The torture and abuse scandal at Abu Ghraib prison occurred in 2002, and by this time the prison had been transferred over to Iraqis, but Task Force 134 still provided support for reopening the prison which was designed to hold 3,500 people in early 2009.

In 2013-2014, Inch oversaw detention operations with Joint Task Force 435 in Afghanistan. As early as 2002, there were incidents of abuse and deaths at the US-run Bagram prison, later renamed the Parwan Detention Facility.

During the years when Inch was in Afghanistan, a UN report revealed widespread abuses. Although control of the Parwan facility had officially been turned over to the Afghan government in March 2013, the US still maintained a hand in the operations. Among the almost 800 detainees interviewed by UN investigators, one-third said they had experienced mistreatment, including being beaten with pipes, electrocuted, and having their fingernails ripped out to obtain confessions. While prisons used by US-led forces in Afghanistan and Iraq have larger prison populations than Guantánamo Bay, the abuses that have taken place in them are far less publicized.

Military-Prison-Industrial Complex

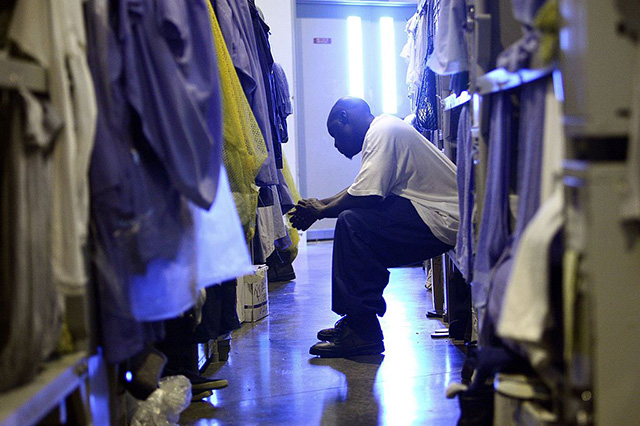

When asked to respond to Gen. Inch’s appointment, people I spoke with who have spent time in federal prison in the US noted that a military culture already exists inside most prisons. Beatrice Codianni spent 15 years in a federal facility and now is managing editor of Reentry Central, a website of criminal legal resources. She told Truthout that, in her experience, the “majority” of corrections officers (COs) had come from the military, and prison officials would recruit at military bases. “These COs had a military attitude that was abrasive and condescending and brought many, many women to tears,” Codianni said. Under Inch, they will likely become “even more aggressive.”

Former political prisoner Susan Rosenberg had her sentence commuted by Clinton and was released after spending 16 years in federal prison. She is the author of American Radical: A Political Prisoner in My Own Country. There is an “increasing connection,” she wrote in an email to Truthout, “between the military-industrial complex and the prison-industrial complex.” She pointed out that UNICOR, the Bureau of Prison’s work program, sells many of its manufactured goods to the military. In the future, she said, we can expect to see an increase of “slave labor” working for military contractors, and the use of solitary confinement and torture. General Inch, she added, is the “perfect person” to carry this out.

Alan Mills — a lawyer at the Uptown People’s Law Center, who has fought to improve mental health conditions and scale back the use of solitary confinement in Illinois — agreed. “The military has a horrible record on the issues of mental health and solitary confinement,” he said in a phone interview, giving the examples of Guantánamo and Bagram prisons. He also mentioned José Padilla, who was picked up at O’Hare airport and, without a hearing or even notice to his family, held in complete isolation for three and a half years in a military brig in South Carolina. Chelsea Manning was put in solitary confinement when she felt suicidal due to the treatment she received in military prison. Mental health is a “growing issue,” with half of people in prisons diagnosed with mental illness, Mills told Truthout. “Prisons in the United States are supposed to be about corrections, not punishment — it’s in the name.”

The sheer size of the prison system that Inch will be overseeing is much larger. The BOP is responsible for housing approximately 190,000 people across 122 facilities, and has some 40,000 employees. “It is of concern that General Inch has no experience in civilian corrections or dealing with a prisoner population that is not only much different than a military prisoner population in terms of literacy, drug addiction, criminal history and mental health but is also over 1,000 times larger,” said Paul Wright, executive director of the Human Rights Defense Center in Lake Worth, Florida.

The appointment is also a setback for those working on reform from the inside of prison. Adam Bentley Clausen, who is currently incarcerated at Federal Correctional Institution, McKean in northwestern Pennsylvania, told Truthout that over the summer, temperatures have soared to beyond 100 degrees. In recent months, since the election of Trump, he said, “the morale of the inmate population has plummeted.”

With General Inch at the helm, we can expect conditions for those incarcerated in federal prisons to further deteriorate.

Note: Thanks to Lois Ahrens, of The Real Cost of Prisons, for assistance with this article.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $48,000 in the next 8 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.