Barrett Brown, who was arrested in 2012 and subsequently imprisoned for his reporting on hacked emails from private intelligence contracting firms, was unexpectedly back in the news recently after he was rearrested during a check-in for “failure to obtain permission” to speak to the press.

In 2011, Brown not only exposed that the private intelligence firm Stratfor had been snooping on activists on behalf of corporations, but also revealed plans by intelligence contractors to hack and smear activists.

Brown pleaded guilty in 2014 to two charges related to obstruction of justice and threatening an FBI agent. Truthout was in the courtroom when he was ultimately sentenced to five years and three months in prison. Last year, Brown won a National Magazine Award for his columns in The Intercept about his experiences in prison. He was released to a halfway house in November and then subsequently released to his residence under house arrest in January. Since May 25, he has been on supervised release.

In a sit-down interview with Truthout at his Dallas residence, Brown detailed his recent rearrest and discussed his ideas for creating new online models for civic engagement and journalism. He also shared some of his plans for what to do next, now that he is no longer incarcerated. The following transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Candice Bernd: Just to start, I wanted to ask you a little about your current house-arrest situation and the terms of your probation. Are you currently allowed to use a computer or the internet?

Barrett Brown: Well, the terms of my supervised-release period, which is set by the court in sentencing, last for two years. It begins five days from [May 20]. Now, the [Bureau of Prisons (BOP)] has nonetheless decided that they have the right to unilaterally interpret those terms of confinement as applying partially to my BOP supervision period, which has gone on for the past six months, and that’s incorrect. So, as soon as I got to the halfway house, I was informed that I could not use computers, the internet or even a PlayStation 4, for instance, because it has internet access, and according to a regional BOP representative, can be turned into a “micro computer,” whatever that is. I think she may have misread an article about the U.S. government having used like 20,000 PlayStation 4s to build a supercomputer.

This is a pattern we’ve seen, when I was in the prison and then outside; most recently, when I was rearrested a few weeks ago for talking to the press, even though, as I showed, that’s not in the BOP policy. You have local officials making up policy, refusing to put policy in writing, calling the [U.S.] Marshals and having them arrest you illicitly, without any documentation, to enforce that, and then backing off when lawyers get involved. That’s pretty much the pattern of the BOP in general.

Can you provide any updates regarding that rearrest incident?

After the lawyers from Haynes and Boone up in New York that Wick Allison of D Magazine hired for me threatened [the BOP], challenging my confinement in a court, they immediately released me. I was taken back to the halfway house, and I hadn’t had a chance to talk to these lawyers since that morning, so I didn’t really know what was going on. I got there and the director of the halfway house took me in his office, and there was some other fellow there who he claimed was his new program director, and said, “Here are these two forms, and the BOP wants you to sign them,” and I said, “Well, what happens if I don’t sign them?” and he said, “Well, we’re back to where we were last week.”

I kept trying to get him to admit that this was again, a threat for a false arrest if I don’t comply with these non-policies. The forms in question, one of them was a form I’d already signed six months prior at my own request. It was a form that allows the BOP to respond to questions about my case in press. Six months ago [the regional BOP representative] had declined to talk to reporters about this computer thing because those forms weren’t signed. So I said let me have that form, and I signed it. So they gave me the same form I had already signed, and then another form, for inmates who are in a prison to give permission to [media representatives to interview them]. So they wanted me to sign this other form, and modified it to apply to this situation.

So, [the halfway house director] made me sign a form that said, “I consent to all future interviews.” This wasn’t the same form that they had brought in last time. They weren’t talking anymore about getting permission for interviews on each individual instance, and they weren’t talking anymore about getting me to have PBS or VICE or whoever sign another form, which again is for getting into a prison. So they backed off that…. I think a decision was probably made, again by the regional [BOP] office, just based on no real legal strategy, just based on kind of a haphazard, wriggling, low-intelligence, imaginary legal strategy. So I said I would sign these forms — they were different forms — if I could take copies with me, and so he allowed that, and I did that.

Since then there’s been no word on it…. I could pursue this, but there’s other things I’d be more interested in pursuing regarding the BOP. So I haven’t come to a decision yet on what to do, if anything. I think it’s actually more important just to show that this is what can happen to you. That’s the thesis I’m trying to present. These things are ingrained in our system. They’re [systemic]. They’re not just, “Oh, these things happen.” This is a [systemic] flaw in our system.

We don’t have the rule of law. We just don’t. It’s a myth, a dangerous myth.

I’m curious to know what other issues you do plan to continue to pursue, journalistically, legally or otherwise, regarding the BOP and the prison-industrial complex, especially as it relates to your own experiences.

I have this book with [Farrar, Strauss and Giroux] that will come out next year. A third of that will be about prisons, not just for the sake of the prison story but also, again, to present my thesis as to what the institutions in this country are actually like, and why they have to be opposed more aggressively. In legal terms, what I’m interested in is a law firm that wants to challenge the constitutionality of the administrative-remedy process. The Prison Litigation Reform Act requires [prisoners], if they want to take someone to court or challenge anything, to go through this long, involved process that the BOP or state prisons, respectively, oversee, and can interfere with at will, as I’ve documented with The Intercept when I went through this process after they took away my email for a year, illicitly. They’ll send you back forms from the regional office, and say, “You’ve got to make three copies of this, and you have until this day to do it,” and that day is negative. It’s 15 days before you received it. So you have negative 15 days to comply. Stuff like that. That didn’t just happen to me. It happens regularly. It’s [systemic]. It’s a shadow policy.

But even when a National Magazine Award-winning journalist presents it in The Intercept, nothing comes of it because it has to hit that threshold that things have to meet for people to care or for Congress to get involved. So, it all flows back into that same thesis, that eventually, we’re going to have to engage in enhanced civil disobedience to get these things changed.

Can you discuss that last point a little more? You mentioned before that journalists should have constituencies to promote this kind of massive civil disobedience, and you talked about your plans for building [an open-source, end-to-end-encrypted collaborative] “pursuance” system platform to build online civic entities that would do just that. Can you explain how this collaborative software will work?

This is something I was attempting to do in 2009. I recruited 75 people, including a core group of professionals and academics, and we were building a system. It was originally supposed to be used to better perpetuate information — for bloggers and journalists to better share information using this mechanism I developed. But it’s expanded since then into what we call a process-democracy platform, a platform for massive civic collaboration. There’s basically a universe. We’re going to seed it with maybe 100 people in different entities — that includes institutions and nonprofits.

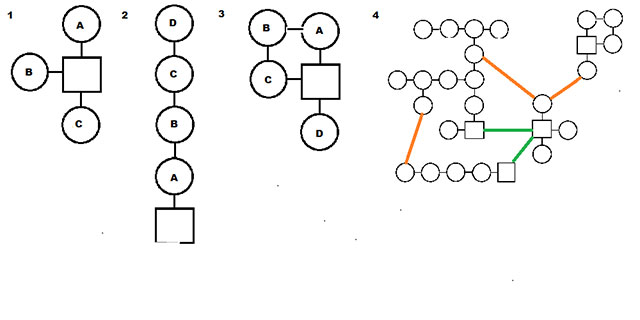

Anonymous, for instance — you have an [internet relay chat] room, and you have people flowing in. How do you decide who has the right to make what arrangements? Who has the right to do what? It’s all very amorphous. It’s very agile obviously, but it also burns out, which is what happened. It was burning out back then. It was subject to all kinds of internal and external threats that just couldn’t be defended against. Now, with this, the mechanism is, you’re in this server, and every other person in this server [has] the same rights. You have the right to create what’s called a “pursuance,” which is an entity. It looks like this:

You are, like everyone else, a little circle in this universe. You can create a sphere. So, having created this entity, you’re in control of its DNA/constitution, its centrality of being. You’re the only one connected to it at first. You define it entirely. Now, as time goes on, you may, for instance, bring people in under yourself, who are answering to you, but who have joined knowing what the role is, knowing what [the] relationship is. It’s a defined relationship. In general, those people have the ability to bring on people under them in different ways. Another way of doing it is, you create one [pursuance], and immediately let several other people have the same rights to it as you. You have several people connected to the central aspects of the pursuance, and you’re sort of running things democratically. Certain things require a unanimous vote or a majority vote among the people who are going to do work connected to it.

Several pursuances [can] connect to each other via both formal connections that are defined between the control of the pursuances, and informal connections that are between different participants. These more formal connections that are decided by whoever has agency over the pursuance, those tend to be more formal. Those are like agreements that say, “We proceed ethically in this particular case. We have this defined set of things we do and don’t do. We have information sharing agreements. We share resources.”

The original purpose of making it like this was intended to figure out how you build something like Reddit, or some other kind of online entity, and expect it to grow without having to worry about the average user base declining in quality — like Reddit for instance. Reddit starts out with early adapters. It’s very informative. You have people providing commentary on articles. It was, for a while, really the most effective way of getting actual information on things. Then it changes, obviously. So how do you get it so that you can expect this thing to grow without having to worry about decline in its quality?

The way [the pursuance] system works, it doesn’t matter if on the margins quality declines, because on the margins, these people are free to bring on people, but they still have to handle them. So if it’s data gathering, for instance, if you’re a journalist or you’re running a crowd-sourced project, and you bring on a few people, each person who’s bringing on people obviously have an impetus to bring on actual quality people to the best of their ability because they have to deal with them, and bad information, useless information, that comes out of these distant [peripheries] on the system are not going to make it up the submission, and there’s a whole mechanism for all of that.

So that was the original impetus. There are a lot of other features that make this work for different things. There’s a great mass of people out there who are tweeting and commenting, and they’re upset, and there’s some portion who are very honest people who are capable, who are knowledgeable, but who are not being provided with a.) the ability to help, and b.) the ability to rise. If you present people the ability to do things correctly, and by doing things correctly, rise to a position where they have the ability to do things on a larger scale, and if you make it apparent that that ability is there, and if we provide examples of it working and provide a degree of leadership, and frankly, propaganda as to why the time has come for this kind of thing, then it will work.

Circumstances have arisen that have made this more viable. The country has deteriorated, and not just deteriorated, but suddenly, and very quickly in a way that’s plain…. So, this or something like it, is inevitable. It’s intended to give rise to a viable, cogent super-organism of opposition.

It sounds like you have a lot in the works, and I wanted to also discuss your next steps. You’ve made statements about seeking citizenship in Germany after your probation is done. Is that still your plan?

That was a decision I came to recently. Whether I move to Iceland or Germany, it doesn’t matter for the future of this [pursuance] project. The foundation will be based here. All that is kind of set. Even if I were to die tomorrow this thing would go forward because we have really good people in place that I managed to find, luckily.

Iceland is a country that is sympathetic to resistance to entrenched institutions. They just knocked down one of their own institutions with street protests. Prior to that, it already had a base of a movement in Reykjavik. [Where I go] can’t be one of the Five Eyes. It can’t be a country … [where] I’d be subject to [arrest]. It has to be something where the U.S. can’t just run in there and grab somebody. It has to be a country that will not easily extradite someone. But Germany, the temperament of the country right now, on the whole, is such that they’re not going to hand me over to the U.S. for whatever reason. And I can’t stay in the U.S. because I can’t get work done if I’m always subject to these little gusts of bureaucracy, which I am. It won’t be for another year or so. I’m on probation for another two years. That generally goes down to one year if you don’t act up. So in a year from now I’ll be in a position to leave.

I wanted to also discuss the lawsuit in California concerning people who have donated to your legal fund. Could you explain that in a little more detail?

So, after I was imprisoned, [supporter and activist] Kevin Gallagher started up the “Free BB” organization to help me out. Among the main things they did was raising money so I could get some private attorneys as opposed to the public defenders I have down here.

He raised like $5,000 at this point. The DOJ [Department of Justice], the prosecutor down here and the FBI agents … decided that they would unofficially subpoena the WePay company that was being used to hold the money, and asked them to provide all information, not just about how much money was in there, but who had donated it — all the information they had, all the identities of the donors, and they obtained that. Meanwhile, they had posted a [court] motion … saying that the money that had been raised to get me private lawyers should instead go to offset the cost of the public defender that I hadn’t asked for, and was planning to replace. Obviously, the real purpose of this was twofold. One was to prevent me from being able to get a private attorney. It’s a very unusual move [for] the DOJ. This “money-should-be-paid” thing, it’s really [an] incentive for people who have been accused of a crime who suddenly win the lottery or have an inheritance or something. Something changes from their original financial circumstance such that a case can be made that they should pay part of the public defender [costs]. It’s never used for someone who has $5,000 being raised to get a private attorney. Obviously it doesn’t make sense because, if I’m going [with] a private attorney, then there will be no cost to the state.

So, this was discovered later on, that that had happened. Over the last few years, Kevin Gallagher had been preparing a lawsuit on it. Gallagher, along with an anonymous donor who is remaining anonymous for the purpose of this [lawsuit], are challenging that move on a number of grounds. There are several legal aspects of this, sort of overlapping, but in some case mutually exclusive, different legal problems with what they did.

One of which is that they did the process very unusually, and sort of contrary to the actual law of how they’re supposed to do these things. Another being that, clearly, there’s a pattern already of them trying to obtain information on my supporters. For instance, they sought to obtain, and did obtain, the identities of everyone who contributed to the Echelon 2 dot org wiki.

So [my supporters] sued for the right for people to donate to politically-oriented causes without being identified by the FBI illicitly, especially when the FBI, in this case, has a pattern of trying to determine your supporters. So [the government has] filed their response. It happened about a week ago [from May 20]. They’re making these claims that, “Oh, no, that’s silly. How could anyone think that? We just wanted to save the state money.” So that will go on for a while. There will be counter-motions and all…. They were asking to settle, and that’s not going to happen.

But that’s something again that can be used to illustrate the actual nature of the DOJ, which is very important now because both parties ignore the DOJ, the FBI and what they do to activists, and what they do to regular people every day, until their partisan agenda is suddenly threatened by it. That’s why you saw the Democrats and the Republicans both seesawing and praising [former FBI Director James] Comey and all that … then changing their minds the next day.

Anything you want to add, or think is important to highlight?

None of this will change until a degree of insurgency becomes acceptable, which it now is to some extent. I know people now who wouldn’t have thought this five, six years ago, now agree with me that the government is frankly illegitimate in many ways and should be treated as such. I think that will become more evident. Let’s say, even if they successfully remove this administration, we still have this 35 percent of people in this country who will support any fascist authoritarian like this, and they’re still there. They may increase in number.

Even under the Obama administration, which was supposed to be the most reasonable, progressive administration ever, these institutions didn’t change. Obama could have changed the BOP through executive order or any number of things. He just didn’t. The point is that we have to realize that we cannot hope to be effective via this system. It’s worked in the past, sometimes, but we’ve also seen republics collapse. We’ve seen republics become untenable.

We’ve already achieved a constitutional police state in this country. We’ve created a country in which 70, 80 million Americans are technically criminal because of all the bizarre drug laws and crime laws we’ve created. That’s an extraordinary fact of this country — that we can only survive as a country to the extent that we do not enforce our own laws. That’s becoming a more visible problem since we had a situation in which both the candidates in the last election probably had committed crimes, and then both sides had to determine why it was OK.

It just goes to show that this whole thing is a charade that no one really believes in. Every time you tell a lie publicly it’s because you don’t agree with the underlying premise of democracy, which is that the people should have the facts. And both sides do it. It’s something that’s in place to keep us from killing each other, but it’s not something that we really deep down, unconsciously, see as legitimate. I think that will become more apparent very easily. It’s very easy for this to all break down.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.