I have lived and worked always in the state of South Carolina.

SC is a high-poverty state (see here and here) with a racially diverse population (ranked 12th highest). And, like many comparable states across the Deep South, SC is a right to work state.

Combined, these characteristics of my home state confirm, I think, my claim about the self-defeating South. However, when it comes to the Great American Worker, the entire U.S. shares that self-defeating nature.

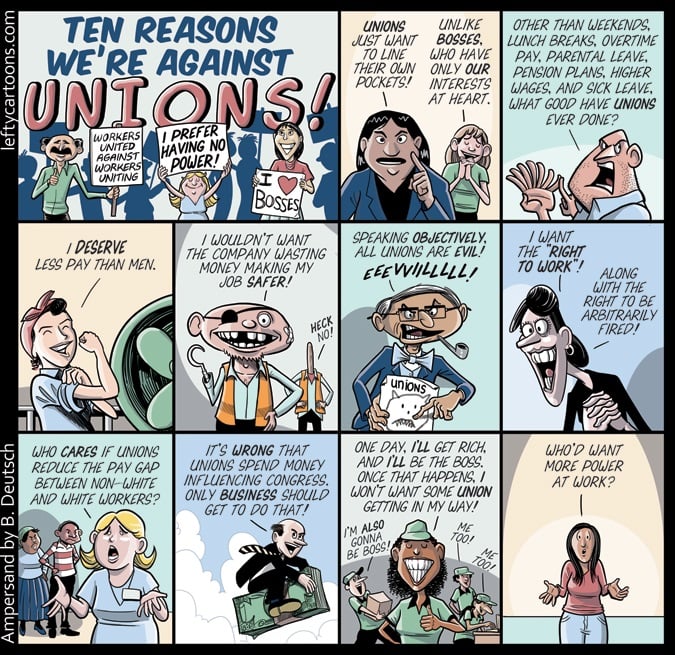

Often that self-defeating quality is represented by political and public attitudes—antagonistic and aggressive—toward workers’ unions.

Current SC governor, Nikki Haley, who is now running for re-election, has taken a seemingly unnecessary stand against unions:

South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley didn’t mince words when she spoke about unions at an automotive conference in Greenville this week. The state loves its manufacturing jobs from BMW, Michelin and Boeing and welcomes more, she explained, but not if they’re bringing a unionized workforce with them.

“It’s not something we want to see happen,” she told The Greenville News.” We discourage any companies that have unions from wanting to come to South Carolina because we don’t want to taint the water.”…

She also warned auto industry executives at the conference to keep their guards up. “They’re coming into South Carolina. They’re trying,” Haley said. “We’re hearing it. The good news is it’s not working.”

“You’ve heard me say many times I wear heels. It’s not for a fashion statement,” she continued. “It’s because we’re kicking them every day, and we’ll continue to kick them.”

And a reader’s letter in The Greenville News represents how the public in SC feels about unions as well as Haley’s stance, arguing in part:

What would happen if unions made an inroad into the Upstate? They would start organizing like mad to try to increase their strength. As more and more employers started having to deal with union demands by raising wages and adding costly benefits, they would need to increase the costs of their products and services. The cost of living would go up for everybody.

I think Gov. Nikki Haley has the right idea.

This reader’s letter as well as the apparent lack of awareness about its self-defeating perspective is perfectly satirized in this cartoon:

Ten Reasons We’re Against Unions! by Barry Deutsch. (Click here to enlarge image.)

Ten Reasons We’re Against Unions! by Barry Deutsch. (Click here to enlarge image.)

While SC political leaders and the public are drawing a line in the sand about unions intruding in the state, Northwestern college football athletes, led by quarterback Kain Colter, have taken unprecedented action to unionize, as Strauss and Eder detail:

A regional director of the National Labor Relations Board ruled Wednesday that a group of Northwestern football players were employees of the university and have the right to form a union and bargain collectively.

For decades, the major college sports have functioned on the bedrock principle of the student-athlete, with players receiving scholarships to pay for their education in exchange for their hours of practicing and competing for their university. But Peter Ohr, the regional N.L.R.B. director, tore down that familiar construct in a 24-page decision.

He ruled that Northwestern’s scholarship football players should be eligible to form a union based on a number of factors, including the time they devote to football (as many as 50 hours some weeks), the control exerted by coaches and their scholarships, which Mr. Ohr deemed a contract for compensation.

“It cannot be said that the employer’s scholarship players are ‘primarily students,’ ” the decision said.

How the public responds across the U.S. to college athletes unionizing must be framed against patterns over the last decade that include a disturbing cultural attitude toward workers, notably against teachers’ unions, tenure, and striking (see the 2012 Chicago strike for example).

Examining how workers are portrayed in the media, how workers are valued (or not) in the U.S., and the prospect of becoming a worker for graduate students, I have framed being a worker within the rise of disaster capitalism and concluded:

Finally, in the wake of disaster capitalism in New Orleans and Oregon, pop culture, specifically The Big Bang Theory, is a crucible of not only the role of workers in the U.S. but also the attitudes about the worker that series highlights. Penny, the stereotypical “girl next door,” is the object of an on-going, clichéd joke of a waitress who longs to be an actress. The larger and central jokes of the series, however, are the four academics living across the hall from Penny. It seems in this TV world, all work is funny.

What a TV sit-com never addresses, however, is that in the real world, the gap between Penny as waitress and college professors is shrinking, or better phrased, merging. The state of the American worker is beginning to share with waitressing some disturbing characteristics that cheapen all workers. As Greider (2013) details about the restaurant industry, workers of all types are becoming less often protected by unions, receiving fewer or no benefits (paid sick days, vacation days, health insurance, retirement) with their positions, being paid less than previous generations, and generally suffering under a dynamic whereby the businesses have more or all of the power in the business-worker relationship.

In the real world, Penny and one of the academics, Leonard, would not be wrestling over the education gap between them, but would be sharing the consequences of part-time work in a hostile economy toward workers regardless of those workers’ qualifications since Leonard would be an adjunct (like Professor Beth) while Penny would remain a waitress—and both would be unsatisfied as workers because their situations do not live up to their ideals.

Yet, most Americans will always be workers, and to be a worker should be an honorable thing worthy of poetic speeches and artistic black-and-white film tributes. Being an American worker doesn’t need to be a condition tolerated on the way to something better, and it shouldn’t be twenty-first century wage-slavery that is a reality echoed in the allegory of SF: “one fine day, a purely predatory world shall consume itself.” As the last paragraphs of Cloud Atlas express, however, the wage-slavery of workers in the context of assembly-line and disaster capitalism is a condition Americans have chosen (or at least been conditioned to choose), but it is also a condition workers can change—if workers believe it is wrong, “such a world will come to pass.” (Academia and the American Worker: Right to Work in an Era of Disaster Capitalism?, pp. 21-22)

A question that remained with me as I drafted the piece above is just why the majority state of people in the U.S.—being a worker—does not inform the pervasive antagonistic attitude toward workers. The public in the U.S. appears just as self-defeating as the South when we are confronted with workers’ rights and collective workers’ voices.

The opportunity before us with the possibility that college athletes may unionize and transform not only their circumstances but also all of college athletics has a less appealing parallel for me, however: The tension between the NFL players’ union and NFL owners in 2011 and how the public responded to that unionization when compared to the rising calls to end teachers’ unions and tenure.

American disdain for unions is grounded in a traditional faith in rugged individualism, but it also seems linked to a good degree of self-loathing informed by a cultural worshipping of the wealthy and famous.

Stated directly and without the political baggage of the term “union,” what are the problems with due process and academic freedom (the central elements of tenure for teachers secured by unionization)? Who prospers from workers without full benefits, strong wages, and safe working conditions? Who maintains control when workers do not have equitable voices in their work and compensation?

Writing about the term “totalitarian,” Ta-Nehisi Coates confronts the power of words (to which I would add “union”):

Words exist within the realm of politics. In politics, words are sometimes perverted by the speaker. It’s worth considering which words come under attack for perversion (“racist,” “homophobe,” “bigot”) and which do not (“democratic,” “bipartisan,” “anti-American”). I am always skeptical of people who seek to curtail their use, instead of interrogating their specific usage. Some people really are racists, and other people really are misogynists, and others still actually are homophobes. Instead of prohibiting words, I’d rather better understand their meaning.

Some people demonizing unions and unionization really are being self-serving, really are seeking ways that workers can be treated as interchangeable widgets (not unlike college athletes) while the owners reap a disproportionate profit on their backs, sweat, and labor (consider how Walmart has sought to bust unions and reduce their workforce to part-time without benefits, resulting in those workers often being on welfare).

Ultimately, Coates comes to workers in the totalitarian state:

But the central idea—that the communist party, and thus the central committee, and thus the politburo was the sole representative of workers—has a chilling moral closure. Who could be against the workers? And if the party is the true representative of the workers, why do we need other parties?

I must echo: Who could be against the workers?

That haunts me, baffles me, leaves me cynical because of all the qualities that divide people in the U.S.—race, class, religion, sexuality, gender—that almost all of us are and always will be workers—a state that should be something of honor and dignity—is the one quality that should unite us.

College athletics stand before the entire U.S. as the crucible of a few benefitting on the backs of many—many without a voice. And that crucible also reveals to us the potential power of a collective voice, an acknowledged voice among the majority who do the labor that generates the profits.

As Coates warns, “words are sometimes perverted by the speaker.”

“Union” is one such word, and when it is spoken by those in power, be certain the motivation is not in the best interests of the workers.

There would be no billionaires today without workers. In fact, powerless workers are nearly essential for maintaining the inequitable state of the U.S. in which billionaires thrive while more and more workers become trapped in multiple part-time jobs, absent benefits or job security.

The Northwestern college football players have my solidarity, but I also wonder why we all are not seeking that same solidarity among every worker in the U.S., a solidarity that could attain the American Dream that has been perverted into an American Winter:

In case it’s not clear, “American Winter” comes from a specifc, biased and unapologetic viewpoint, but it’s also the kind of argument that’s needed right now. Watching the 50 year old John, 3 years unemployed and father to a young son with Down’s Syndrome, weep on camera because he had to borrow money from his parents to pay the electric bill, it’s bracing and raw. When Paula goes to the food bank for the first time, and is overwhelmed by the fact that her situation has forced her to take such measures or when single mom Jeanette tries make a promise to her young son Gunner that they will find a place to live, it puts a new perspective on those who are traditionally associated/stereotyped as being on social services. Everyone in “American Winter” has been working, are raising families, and doing everything they can (Dierdre gives blood and goes scrapping on weekends just for extra money) to make ends meet. They are not the vultures of the system that certain political segments like to paint as living on taxpayer money. (Review: ‘American Winter’ A Devastating Portrait Of The Erosion Of The Middle Class)

That recovered American Dream could be built on workers unionized for the right to work—the right to work for wages that dignify their work and their lives, the right to work as a part of their right to live fully and freely, the right to work in a physically and psychologically safe environment, the “right to work” not perverted by a political elite bragging about using high-heeled shoes as the boot on the throat of the Great American Worker.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $24,000 by the end of today. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.