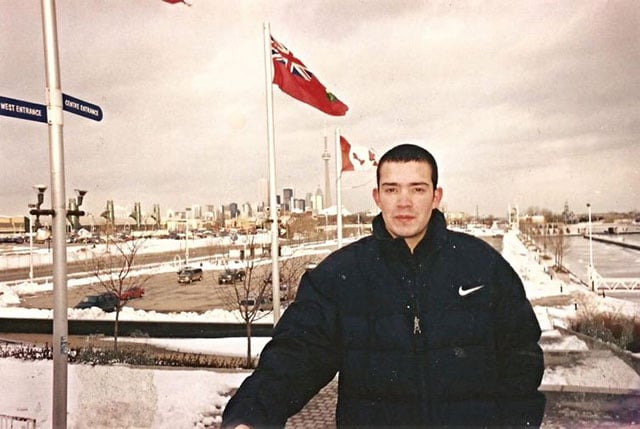

The Canadian government has yet to offer an explanation as to why Francisco Javier Romero Astorga, a 40-year-old father of four, passed away while in the custody of the Canadian Border Services Agency. (Photo: Family Photo / Courtesy End Immigration Detention)

The Canadian government has yet to offer an explanation as to why Francisco Javier Romero Astorga, a 40-year-old father of four, passed away while in the custody of the Canadian Border Services Agency. (Photo: Family Photo / Courtesy End Immigration Detention)

Francisco Javier Romero Astorga, an immigrant to Toronto, Canada, was in search of a “new beginning,” his family says.

A music lover and passionate chef, Astorga struggled to find work in his native Chile, so in October 2015 he left for Toronto. He had high hopes that Canada — where he had lived from the mid-1990s to early 2000s — would again provide him and his family with better opportunities.

But early this year, the Astorga family learned that Francisco had been arrested, and in March, devastating news arrived: the 40-year-old father of four was dead.

“We need answers and no one is giving us any.”

“Francisco left Chile in perfect health, he spent much of his most recent time in Canada in immigration detention custody and now he is dead,” his family wrote in an open letter shortly after Francisco’s death on March 13.

He died in the custody of the Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA), the body responsible for Canada’s border crossings and enforcement of immigration policies, at a provincial jail in Ontario.

But details on the circumstances of Francisco’s death are scarce, and the Astorga family is still seeking answers.

“We need to know how many days was Francisco in detention? Was he in the cell alone or was he with someone else? Was he exhibiting signs of ill health, or psychological stress in advance? Did he call for medical care? Who was responsible for checking in on him? When was the last time he was seen alive? What did the doctors do when they found him? What is the cause of death?” said his brother, Esteban, in a recent statement.

“We need answers and no one is giving us any.”

Calls for Independent Oversight

Astorga’s case drew national headlines because he died in the same week as another immigrant detainee, 64-year-old Burundian refugee Melkioro Gahungu, who reportedly hung himself in prison. Then, in May, a 24-year-old man whose name remains unknown, died in detention in Edmonton.

At least 15 people have died in immigrant jails in Canada since 2000, and the recent deaths have prompted calls for Canada to reform its immigrant detention system.

“We are breaking international law. Canada is a rogue nation.”

Detainees want a 90-day release period if they are not being deported, while medical and mental health professionals, refugee rights groups and legal experts are urging Ottawa to establish an independent body to supervise the CBSA.

That’s a longstanding demand that the Canadian government has ignored for years.

“There is nothing formal that exists for CBSA,” said Janet Dench, executive director of the Canadian Council for Refugees, adding that there is a lack of accountability “in terms of being able to show that detention was necessary.”

That lack of clarity also makes it difficult to know what obligations the CBSA has toward the family of someone that died in detention, or who pays to repatriate a body, Dench explained.

Francisco Javier Romero Astorga poses with his Grandmother, Maria Ester Lamas Yañez, and sister Maria Teresa Romero Astorga. (Photo: Family Photo / Courtesy End Immigration Detention) She said the establishment of an independent mechanism is critical to make it possible to monitor the CBSA and its decisions, to handle complaints and to answer questions that family members may have about why a loved one is detained.

Francisco Javier Romero Astorga poses with his Grandmother, Maria Ester Lamas Yañez, and sister Maria Teresa Romero Astorga. (Photo: Family Photo / Courtesy End Immigration Detention) She said the establishment of an independent mechanism is critical to make it possible to monitor the CBSA and its decisions, to handle complaints and to answer questions that family members may have about why a loved one is detained.

“It has been established over the years that there has to be an independent oversight mechanism for police forces, but somehow we haven’t shone the same light to the border officials that also have powers of arrest and detention,” she said.

“It’s a very serious problem, and the more you have people detained, the more there is the risk that people will die in detention,” she said.

Power to Arrest and Detain

The CBSA has the power to detain individuals that cannot identify themselves, or who are perceived as a threat to public safety, or flight risks.

Similarly to the United States, immigrants can be detained at Canadian border crossings, including airports, and CBSA officers can also arrest and detain individuals anywhere in Canada.

Most immigrants are held under Canada’s Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, meaning they are detained under administrative laws. But like in the US, they can be held in federal and provincial jails alongside individuals detained for criminal offenses.

While the average length of detention is around 23 days, immigrants can be detained in Canada for indefinite periods of time, especially when Canadian officials cannot deport them to their home countries.

“We are breaking international law. Canada is a rogue nation,” said MacDonald Scott, a lawyer with the Immigration Legal Committee of the Law Union of Ontario, during a recent protest in Toronto calling for an end to immigrant detention.

Michael Tan, a lawyer on the Immigrants’ Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), said immigrant detention periods are longer in the United States when deportation does not occur quickly. That is often the case if a detainee is stateless, or his or her country of origin does not take back its nationals.

“One of the things we’ve seen in the US is the increasing intersection of our criminal justice and immigration systems,” Tan told Truthout.

“So right now, in our federal criminal prisons, the fastest growing part of the population in there are people who are being jailed and sentenced and serving criminal sentences for immigration violations, like either crossing the border illegally in the first place or coming back after being ordered deported.”

Smoke and Mirrors

In Canada, the CBSA rarely releases names or the details of deaths in custody, but it says it launches investigations immediately after these incidents occur.

“The CBSA takes all deaths seriously and will complete a review of the circumstances surrounding the deaths to identify any factors that could be addressed to prevent any future loss of life,” CBSA spokesperson Wendy Atkin told Truthout in an email.

A decision to detain someone is subject to a review by a representative of the Immigration and Refugee Board, an independent tribunal that rules on immigration matters, Atkin said. The first detention review is conducted 48 hours after a person is detained, then within seven days and every 30 days thereafter.

“Detention is always a last resort,” she said.

But a study published last year at the University of Toronto described Canada’s immigration review process as “an exercise in smoke and mirrors” that facilitates rather than mitigates the risk of indefinite detention.

“Ontario counsel we spoke to uniformly expressed frustration with the futility of the reviews, where a string of lay decision-makers preside over hearings that last a matter of minutes, lack due process, and presume continued detention absent ‘clear and compelling reasons’ to depart from past decisions,” the study found.

In 2013-2014, the CBSA held 10,088 immigrants — almost one-fifth of them refugee claimants — in various facilities, including federal holding centers and provincial and municipal jails, the Canadian Press recently reported.

Of that number, 197 minors were detained and held for about 10 days each on average.

Earlier this year, an unaccompanied, 16-year-old Syrian boy was held in solitary confinement for three weeks after seeking asylum at the Canadian-US border. Dench described that case as “absolutely inappropriate and absolutely absurd.”

The whole system, she added, “falls into a pattern of treating the rights of non-citizens as being less of concern to us than of the citizens.”

An Alternative to Detention

A spokesperson for the Office of Canada’s Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Minister told Truthout in an email that Ottawa is examining the CBSA’s immigrant detention program and how best to establish a review mechanism.

“We are working now on a number of very important revisions to issues related to detention in our immigration and border system,” Minister Ralph Goodale told a Senate committee on May 30. “I hope to put those proposals forward later on this year.”

Last year, a UN committee of human rights experts stated that Canada “should ensure that detention is used as a measure of last resort, that a reasonable time limit for detention is set, and that non-custodial measures and alternatives to detention are made available to persons in immigration detention.”

In mid-May, the CBSA posted a government tender for a community supervision program that could serve as an alternative to detention. Such a program could include fixed residency, community services to mitigate risk during release periods, as well as the use of “electronic supervision tools” for people detained under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act.

But Laura Track, a staff lawyer at the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association, said deep, structural changes are needed to reform how Canada uses detention for individuals without legal status.

A focus also needs to be placed on the CBSA’s “day-to-day policing activities,” she said, rather than simply on national security operations.

“What we haven’t seen is a clear commitment to subject CBSA’s policing activities to that same kind of oversight and accountability. We’re uncertain as yet where the government stands on that,” Track said.

She added that while creating an oversight body for CBSA is a good first step, the problems with immigrant detention in Canada are structural and “run much deeper” than a lack of oversight.

“There are major changes that need to happen to the way immigrants are dealt with and to the way that detention is used for people who are in Canada without legal immigration status,” she said.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.