Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

Ask Randi Weingarten, president of the 1.7 million-member American Federation of Teachers (AFT), what public schools need in order to safely reopen this fall and her answer is immediate: more money for the daily deep-cleaning of schools; personal protective equipment (PPE) for teachers, staff and students; the hiring of thousands of additional school nurses and counselors to help students navigate social and emotional roadblocks; reliable computers and internet access for every kid; and a 10 percent increase in the number of instructors so that class size can be reduced.

The total cost estimated by the AFT: $116.5 billion, or $2,300 in additional funding for each and every one of the 51 million kids who currently attend U.S. public schools.

“We need 20 percent more money to reopen schools, not 20 percent less as has been proposed,” Weingarten told Truthout. “This is a national emergency. State governments have had the bottom fall out in terms of revenue so the federal government has to provide support to the states. If they don’t, it will be a moral dereliction of duty.”

What’s more, Weingarten argues that Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has been a particularly ineffective leader when it comes to supporting public education. In contrast, when the Supreme Court issued its decision in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue in June, allowing families to use tax-credit money to enroll their children in private religious schools, the Department of Education (DOE) acted quickly. “Within 48 hours of the Espinoza decision, the department opened the door to taxpayer funds going to private Christian academies. This proves that they can move at lighting speed when they want to,” Weingarten says. “But when it comes to the digital divide, child hunger or problems with remote learning, DOE has been stone-cold silent, showing their blatant antipathy for public education.”

Drastic Cuts Proposed

Not surprisingly, this antipathy has hurt students and frustrated educators. Rather than offering the kind of massive cash infusion that Weingarten says is needed to buttress public education, the feds have thrown up their hands, leaving the country’s 13,000 school systems on their own to deal with humongous budget gaps due to reduced sales, property and income tax payments. And while teachers’ unions and education activists are pushing back against austerity and are suggesting ways to save money — including the removal of police in schools — many students are poised to return to class, whether in-person, online, or in a hybrid form that blends remote and in-person learning, without the tools they need to succeed.

In Utah, for example, the public education budget will likely be slashed by $385 million, while in Mississippi, a projected budget shortfall will reduce instruction from 5.5 to four hours per day.

In Massachusetts, more than 2,000 public school teachers were sent termination notices in June.

New Jersey, meanwhile, is gearing up for $7.3 billion in overall budget cuts due to lost revenue.

Similarly, Georgia is cutting education funding by 14 percent, prompting schools in Catoosa County in the state’s northwest to shorten the school year from 175 to 170 days.

Public higher education is also feeling the pinch, the result of a $76.3 million reduction in state contributions to both two- and four-year colleges.

“We need billions earmarked for public education,” Lily Eskelsen Garcia, president of the National Education Association, told Truthout. One way to get that money, she says, is through congressional passage of the HEROES Act, a $3-trillion general relief bill that allocates monies to floundering schools. The Act, passed by the House in May, is now stalled in the Senate. “The HEROES Act is not perfect, but it is a good down payment on what we need,” Eskelsen Garcia says. “Schools that have the least — high-poverty schools — would get the most. It would also keep massive layoffs from happening.”

Additional federal funding, she concludes, is also the only way to ensure that public schools are able to provide the academic and social supports that students need in order to learn.

This is especially true for students who are homeless. An estimated 1.5 million public school students experienced homelessness during the 2017-18 school year, and an additional 550,000 unaccompanied minors are currently homeless in the U.S., with that number likely to rise as eviction moratoriums expire.

“The funding that Congress has provided so far has not specifically targeted students without homes,” says Barbara Duffield, executive director of the Washington, D.C.-based group, SchoolHouse Connection, which advocates homelessness prevention through education. “Unlike relief provided after disasters like Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy, which mandated that relief dollars go to homeless students, coronavirus relief can be used for homeless children, but it doesn’t have to.” The end result, she says, is a “lack of continuity in communities with homeless kids,” many of whom are unaccounted for.

“Because of the pandemic, shelters started to limit who could come in and out, and people became fearful about going into a shelter because of the virus,” Duffield tells Truthout. “Nonetheless, the most stable place to stay if you’re homeless is often a shelter, but this has become less of an option due to the pandemic.” In addition, she notes that people who have been living doubled up with relatives or friends may be experiencing increased tensions due to quarantine, and may now be facing additional housing or personal insecurities — something Duffield says needs to be addressed by advocates in and outside of the educational system.

Legislative Relief Sought

There are, of course, no magic bullets, but Duffield and SchoolHouse Connection are supporting the Emergency Family Stabilization Act — introduced by Senators Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), Joe Manchin (D-West Virginia) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-Arizona) in June — as a step in the right direction. As written, the Act will provide $800 million to community-based organizations to meet the needs of homeless children, families and unaccompanied minors for the duration of the pandemic. Although the bill has not yet been introduced in the House, passage will provide funding for hygiene supplies, PPE, and mental and physical health care; financial assistance for eviction prevention, utility payments, and motel and other short-term housing placements; as well as education and job-readiness training.

Duffield is particularly supportive of the bill, she says, because it provides access to funding for people who currently fall outside of the official definition of homelessness used by the Department of Housing and Urban Development — including toddlers and infants, folks holed up with friends or family, or those staying in hotels.

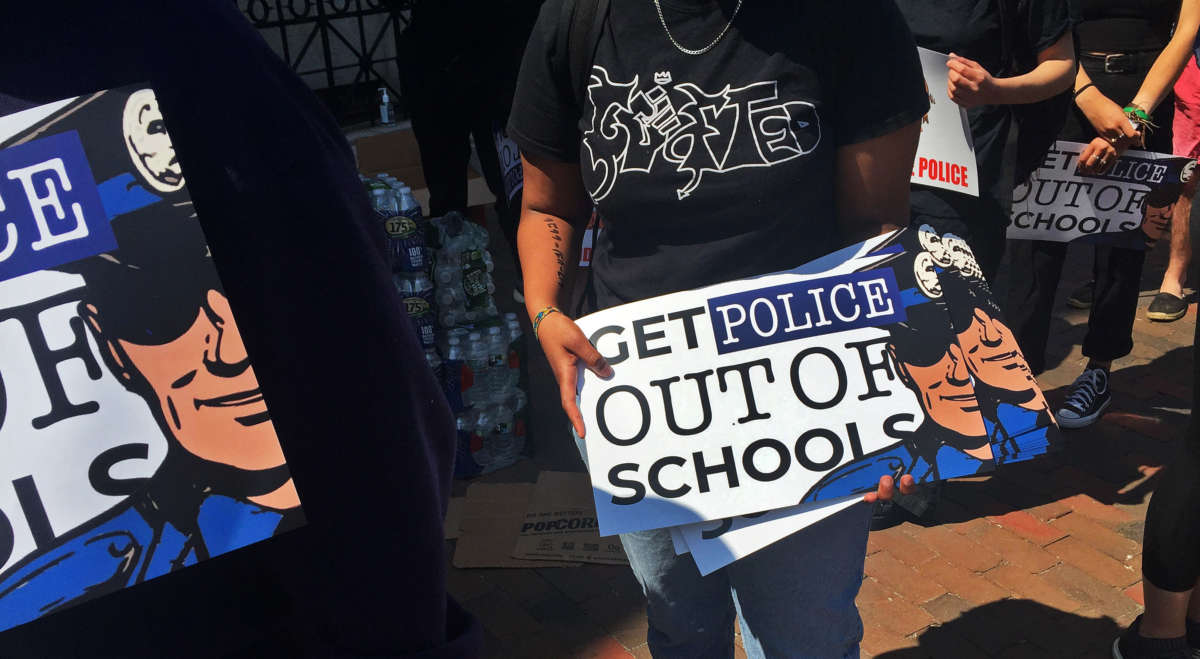

But while upping federal spending for schools is essential, many activists are also organizing to remove police — typically called school resource officers, or SROs — from schools throughout the country. This, they argue, will not only save school systems approximately $960 million annually, but will enhance learning for public school students, the majority of whom are Black and Brown. What’s more, they note that study after study has shown that students of color are disproportionately subjected to harsh discipline for small infractions, resulting in arrest and prosecution in criminal court, often a first step toward prison.

Jonathan Stith, national coordinator of the Alliance for Educational Justice, a national network of youth-led organizations working to end the school-to-prison pipeline, says that the campaign for police-free schools began in 2015 after high school student Niya Kenny filmed School Resource Officer Ben Fields body-slamming a 16-year-old student, identified only as Shakara, at Spring Valley High School in Columbia, South Carolina. Although Fields was ultimately fired, Stith told Truthout that students and allies came together because they were “tired of states and localities telling them that they were too broke to fund transformative justice programs or hire additional school counselors, but always had money for more police. After the Parkland shooting in February 2018, overnight, municipalities found millions for policing the schools.”

This laid the groundwork, Stith says, for the current movement to end in-school policing, a movement that has had limited success in Oakland, San Francisco and San Jose in California; Portland, Oregon; Denver, Colorado; St. Paul and Minneapolis in Minnesota; and Seattle, Washington.

According to The Center for Popular Democracy, activists in numerous additional locations — including Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Orange County, Florida; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Rochester, New York; and Salem, Oregon — are continuing to agitate and organize for police-free schools.

“It comes down to political will,” Stith says. “As Martin Luther King [Jr.] said, budgets are moral documents, and no one wants to send their kids to an over-policed and under-resourced public school.”

Making Police-Free Schools the Norm

But we still have a long way to go to make police-less schools the norm. According to NPR, almost 90 percent of U.S. schools have full- or part-time police officers on campus, something that became commonplace after the 1999 Columbine High School shooting in Littleton, Colorado.

Initial funding for SROs — in the millions — came from the Department of Justice.

Contracts are huge: Chicago Public Schools, for instance, spend $33 million a year on 144 SROs, 48 mobile officers and 22 staff sergeants.

In Vermont, districts report spending between $50,000 and $80,000 per officer, a total of more than $2 million a year. The result? In the city of Burlington, Black students comprise 16 percent of the student body but account for 61 percent of arrests. Statewide, just 2.4 percent of Vermont’s students are African American; nonetheless, 23.3 percent of those arrested in school are Black.

Despite these disparities, Burlington voted to keep SROs in place for another year pending a task force investigation to evaluate their efficacy. Police officers will also remain in New York City and Chicago schools through 2021.

Meanwhile, schools continue to scramble for resources, a situation that has been exacerbated — but was not caused — by COVID-19. For their part, students, teachers and staff continue to wonder what education will look like come fall.

June 2020 high school graduate Noelle Salaun is heading to Hunter College-City University of New York in late August, but says that she is concerned about her course of study as a fine art major. “Setting up an appointment with the financial aid department, or with a counselor to fix my schedule, has been nearly impossible,” she told Truthout. “I’m worried that I won’t get the most out of my classes. I’m taking a theater course. How will I perform scenes if classes are online?”

But what is instilling the most fear in Salaun is the unanswered questions about how her education will proceed as the pandemic drags on.

Salaun is not alone. Students, teachers and school support staff are concerned about the many unknowns facing them. At the same time, something else is also lurking: Thanks to the upheaval caused by COVID-19, they’re also seeing fall 2020 as an opportunity to create public schools that nurture, inspire and truly educate.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $44,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.