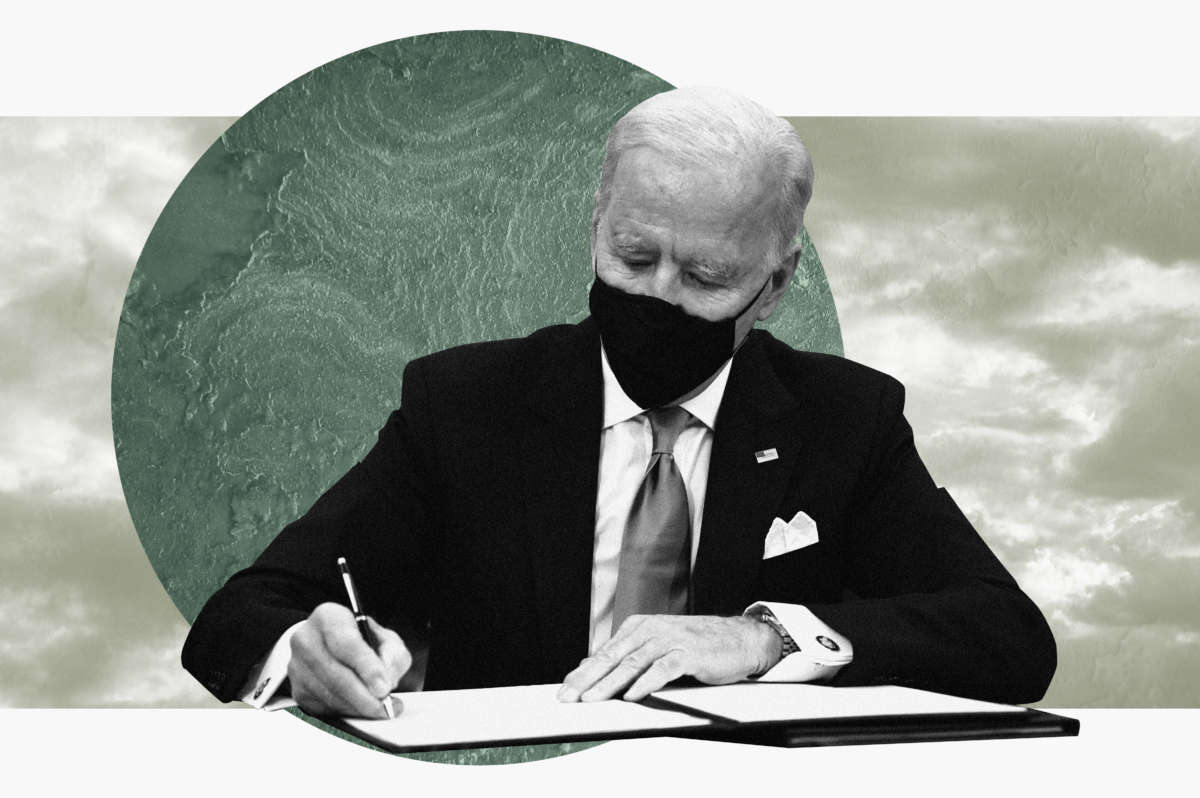

Shortly after getting settled in the Oval Office on his first day on the job, President Joe Biden delivered on his commitment to re-join the Paris Agreement, the 2015 pact adopted by almost every country in the world to curb climate change in an attempt to effectively stave off a sixth mass extinction. The signature was his third in a stack of 17 executive orders. Now the Biden-Harris administration will send a letter to the United Nations announcing the decision, and the U.S. will officially be a party to the agreement again in 30 days.

Climate scientists and scholars, who watched with horror as the U.S. officially pulled out of the agreement on November 4, 2020, say Biden’s move is more than merely symbolic, but it is only a starting point. “Every other diplomatic channel at our disposal is necessary to support climate action,” director of climate policy at Ocean Conservancy, Sarah Cooley, told Truthout. “We also need to see climate considerations re-emphasized in all parts of the government. We need to tackle this crisis from all sides and that means taking action through all of the federal agencies, legislation and executive powers,” she said.

The Paris Agreement established a 2 degrees Celsius upper limit of warming in an attempt to stave off the most calamitous impacts of climate change, like temperatures too high to sustain human life and sea level rise that envelops whole cities. Members of island nations made the case that a more ambitious limit, “1.5 to stay alive,” was the only benchmark that gave countries on the frontlines of the climate crisis a fighting chance. Climate activists who protested outside of the Paris summit called the agreement a “death sentence” for people in many parts of the world due to its inadequacy.

The global average temperature is already dangerously close to both limits, at almost 1 degree Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures. We are currently on track to burn 120 percent more fossil fuels by 2030 than what would enable warming to be limited to 1.5°C, according to a 2020 UN special report.

Since former President Trump filed notice that the U.S. would ditch the Paris Agreement in late 2019, we’ve lived through the second-hottest year ever recorded. In 2020, flames engulfed the globe. “Zombie fires” smoldered below ground in Siberia and the number of fires tripled in the world’s largest tropical wetlands, the Brazilian Pantanal. Heavy rains pushing at the banks of the Tittabawassee River breached two dams in central Michigan, prompting thousands of people to evacuate. Locusts descended on Kenya again, causing many farmers to lose a whole season’s harvest in 24 hours.

Nicaragua and Honduras were hit with back-to-back record-breaking hurricanes, which killed over 100 people and impacted an estimated 4.7 million, according to the Red Cross. Weeks later, a caravan of asylum seekers were met by Guatemalan police who attempted to prevent them from traveling through the country using riot shields and tear gas. “We have no work. We can’t go back,” a member of the caravan told The Guardian. “Back home we’re dying of hunger.”

With the U.S. remaining on the sidelines of the global climate agreement, other countries have continued to develop increasingly detailed plans mapping out how each government will adhere to domestic policies in line with each country’s emissions goals that theoretically stack up to a global net-zero emissions outcome by 2050. The individualized blueprints are known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement. All parties to Paris submitted initial plans shortly after the agreement was signed. Updated versions are due ahead of the next global climate convening, COP26, in Glasgow.

The Biden-Harris administration needs to not only meet but exceed its previous commitments, professor of global governance at UMass Boston, Maria Ivanova, told Truthout. “The global community is looking to the United States and assessing its trustworthiness,” she said. The U.S., which is responsible for the largest cumulative share of greenhouse gas emissions to date since 1750 — submitted its first and only NDC plan to the United Nations in February 2016. The document stated a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, including carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. The five-page plan includes a short list of domestic laws, regulations and measures that suggest how it might achieve this goal, mentioning that the Environmental Protection Agency “is developing standards to address methane emissions from landfills and the oil and gas sector.”

In reality, the Trump administration weakened rules requiring oil and gas companies to find and plug methane leaks, which Scientific American reported could result in an additional 4.5 million metric tons of methane annually, or the equivalent of bringing 100 coal-fired power plants online each year.

By comparison, Bangladesh, which is responsible for .22 percent of carbon dioxide emissions, committed to reducing its greenhouse gasses 15 percent by 2030 from “business as usual.” Its 2016 NDC plan is accompanied by a detailed list of domestic policy prescriptions, like laws that require a shift toward the use of organic rather than synthetic fertilizers and move waste from landfills to composting systems.

Along with 44 other parties , Bangladeshi officials submitted an updated plan in December 2020, which details its plan to “ratchet up” policies to deliver on its reductions goals, and includes a national solar energy roadmap spanning 2021-2041 and a program to roll out clean cooking stoves to reduce emissions from burning biomass. The U.S. never updated the UN’s registry with any such roadmap of domestic policies that would reasonably result in a 25 percent emissions reduction by 2025.

“Ultimately, the ability of the U.S. to step up on the international front will depend on what the Biden Administration is able to deliver on an ambitious domestic climate agenda,” policy director with the Climate and Energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, Rachel Cleetus, recently wrote on the organization’s blog. “If Congress and the Biden Administration step up, the U.S. can deliver economy wide emission reductions on the order of at least 50 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, and it can at least double its initial $3 billion commitment to the Green Climate Fund over the next four years,” she wrote.

The Green Climate Fund is the largest existing fund to aid developing countries in addressing climate change, which was established by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2010. The U.S. failed to meet its initial commitment to the fund, only one third of which was disbursed under the Obama administration.

According to Ivanova, establishing resilience offices in every city will be a critical first step to delivering on domestic policy, as well as the rollout of innovative transportation systems that do not assume individuals investing in a Tesla or a Prius. “[Everyone] should have the option to take zero emissions, high efficiency flying trains to work,” she said.

To prevent the creation of new environmental and human rights catastrophes in the shift to building full-city fleets of electric vehicles, burgeoning solar fields, offshore wind farms and distributed battery sites, the Biden-Harris administration must also commit to fair-trade agreements with countries home to deposits of raw materials like cobalt, nickel and lithium that are key to building these new technologies, Thea Riofrancos told the HuffPost. “When you go to the extractive frontier, you see the hyper exploitation of labor, contamination of ecosystems and violations of Indigenous rights,” Riofrancos said. Scholars have also pointed to the importance of improving recycling capacities for those materials to limit the need for extraction — in other words, developing a robust circular economy.

Among climate activist circles, the decision to re-join the agreement has been praised, but with reserve. Cancelling the Keystone XL pipeline without also shutting down Dakota Access and Line 3 would prove signing the Paris Agreement an empty gesture, some say. Youth climate activists from outside the U.S. have called on President Biden to “be brave,” to hold polluters accountable and to ramp up support for COVID relief packages that decarbonize the economy faster than the Paris Agreement calls for.

Edgar McGregor, a 20-year-old climate activist who carries out weekly trash cleanups in Los Angeles, likened Biden’s rejoining the Paris Agreement to children promising to do their homework. “It is great, but what lies ahead of us is tons of work, and we need to get started on it,” he said. “We did not elect Joe Biden to make promises, we elected him to make the right things happen. I’ll be expecting much, much more climate action from his administration.” Activists with the Sunrise Movement are holding protests across the U.S. today, demanding the Biden-Harris administration pass a sweeping jobs bill that addresses the climate crisis head-on.

In the first tweet from his official new account, Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry indicated he sees the need for deeper change, calling the Paris Agreement “a floor, not a ceiling,” for U.S. climate leadership. “Working together, the world must and will raise ambition,” Kerry wrote. “It’s time to get to work — the road to Glasgow begins here.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $44,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.