This is part of a special report by YES! Magazine: The Spirit of Standing Rock on the Move.

Sometime last year, the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota became not just a physical location but an iconic challenge to the national conscience. Like the Selma Civil Rights Marches in 1965 or the Frank’s Landing Tribal Fishing-Rights Demonstrations in 1970, Standing Rock’s water protectors, as they all themselves, have transformed ideas of advocacy and resistance with nonviolent direct action and prayer. They have built coalitions across movements for tribal sovereignty, defense of natural resources, resistance to expanding energy infrastructure, and cultural survival. They have shown the world a culture grounded in stewardship and connection to earth.

Above, horseback sentinels on the hilltop above the encampments. (Photo: Joseph Zummo)

Above, horseback sentinels on the hilltop above the encampments. (Photo: Joseph Zummo)

The resistance that persisted even through the cold and dark of the North Dakota winter, with ongoing injuries and arrests, shows how difficult, dangerous, and uncertain it can be to speak truth to power.

Now the spirit of Standing Rock is on the move.

Its Native-led, youth-driven expertise is extending outward to help other communities protect their land and resources. In Texas, Frankie Orona, from the Borrado, Chumash, and Tongva people, is leading actions against the Trans-Pecos Pipeline, which will carry fracked gas across Texas and into Mexico, if completed. For months, he and others have danced, prayed, and sang in the path of the line. Recently, they were arrested after locking themselves to construction equipment. In December 2016, after consulting with the Indigenous Environmental Network, which was central to organizing the Standing Rock resistance, Orona’s group established a camp and built a Native/non-Native support system, similar to Standing Rock’s, with backing from local environmentalists and ranchers. One rancher is hosting the camp on her property.

Standing Rock has also been evoked in Florida and New Jersey, where Natives and non-Natives have united to object to the Sabal and Pilgrim pipelines, respectively. In Florida, four camps were recently established to protest the Sabal line, and on January 6, Dallas Goldtooth of the Indigenous Environmental Network went live on Facebook to urge Standing Rock water protectors to go support these other fights.

Elsewhere, Native people are standing up for mountains. In Hawai’i, conflict rages over placing another telescope on the holy peak Mauna Kea. Prayer gatherings, blockades, arrests, declarations of Native self-determination, and a lawsuit have blocked the project so far. In Arizona, longtime protests have also sought to roll back desecration of Mount Graham, where a telescope mars the sacred summit, and the San Francisco Peaks, contaminated by wastewater that a ski area uses for snow-making.

Certainly the Standing Rock campaign has inspired wider interest in Native struggles, agrees Judith LeBlanc, director of the Native Organizers Alliance and member of the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma. “People everywhere are talking about Standing Rock, which has magnified the reality of other situations like it,” says LeBlanc. She calls the awareness a “Flint moment” for Indian Country.

And she is optimistic. She notes that tribal struggles are ever more successful: “Stopping drilling in the Arctic and a giant coal export terminal in the Northwest, canceling oil and gas leases in a Blackfeet cultural landscape — these successes have been Native-led,” LeBlanc says. As Shoshone-Bannock professor and pundit Mark Trahant has pointed out in YES!, the end of these stories is no longer “inevitable,” with Native communities always losing to outside interests.

Chief Arvol Looking Horse, 19th Generation Keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe, spiritual leader of the of the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota Nations. (Photo: Joseph Zummo)Tribal advocacy has helped protect more places in recent weeks.

Chief Arvol Looking Horse, 19th Generation Keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe, spiritual leader of the of the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota Nations. (Photo: Joseph Zummo)Tribal advocacy has helped protect more places in recent weeks.

In Colorado, the Piñon Pipeline will not go forward, the company that was planning to build it has announced. In the last weeks of President Obama’s term, he protected the ancient spiritual places and magnificent scenery in southern Nevada as the nearly-300,000-acre Gold Butte National Monument. He did the same for 1.35 million acres in southern Utah, now the Bear Ears National Monument. Notably, at Bear Ears indigenous people will contribute to ongoing management decisions. Though state and congressional officials have said they will fight both monument designations, such actions are difficult to unwind.

“The United States needs us Native people,” says Wendsler Nosie Sr., a former San Carlos Apache tribal chairman and leader of Apache Stronghold, a group formed to protect a sacred landscape in Arizona. “Without us taking the lead on these issues, there would be chaos. As a country, we have to choose a better way of being.”

Right, the entrance to the Oceti Sakowin camp is lined with flags from visiting tribes. (Photo: Joseph Zumo)Native-led campaigns take place in courtrooms, legislatures, and other government chambers. They also occur during face-offs on the prairie, desert, and tundra. “So far, we haven’t had to stand in front of bulldozers,” says Kimberly Williams, Curyung tribal member and director of an Alaska Native group seeking to protect the massive Bristol Bay salmon fishery from a proposed mine. “But I’m ready to.”

Right, the entrance to the Oceti Sakowin camp is lined with flags from visiting tribes. (Photo: Joseph Zumo)Native-led campaigns take place in courtrooms, legislatures, and other government chambers. They also occur during face-offs on the prairie, desert, and tundra. “So far, we haven’t had to stand in front of bulldozers,” says Kimberly Williams, Curyung tribal member and director of an Alaska Native group seeking to protect the massive Bristol Bay salmon fishery from a proposed mine. “But I’m ready to.”

“What we learned at Standing Rock is the power of unity,” says Orona. “Hundreds of indigenous nations from all over the country and the globe stood together, along with supporters, and that endures.”

By the end of November 2016, more than 300 tribes were represented at the Standing Rock camps. Back home, each tribe faces its own struggle against government and industry, with decades of destruction and injustice behind and years of fighting ahead.

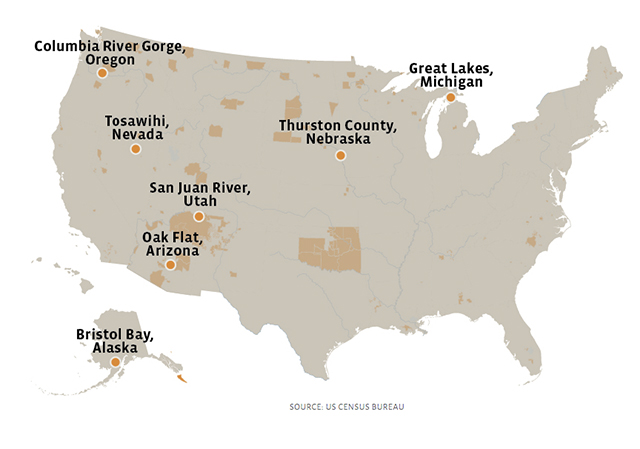

Indian Country in the US

Before there were states, there was Indian Country. In 2016 there were 326 federally recognized American Indian reservations. About 22% of the 5.2 million Native Americans live on tribal lands. Click on the points on the map below to explore seven stories of Native resistance.

A diver inspects the aging and barnacle-encrusted Enbridge Line 5 oil pipeline that lies under the Straits of Mackinac, which connect Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. (Image: Still from National Wildlife Federation video)

A diver inspects the aging and barnacle-encrusted Enbridge Line 5 oil pipeline that lies under the Straits of Mackinac, which connect Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. (Image: Still from National Wildlife Federation video)

Great Lakes, Michigan

“An accident waiting to happen” is how Chairman Aaron Payment of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, in Michigan, described aging, mussel-encrusted pipelines carrying 540,000 barrels of oil and natural gas daily through the Straits of Mackinac in the Great Lakes.

“It’s very frightening,” agrees Stella Kay, vice chairwoman of the nearby Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians, in Harbor Springs, Michigan.

The protests at Standing Rock have called attention to the proliferation of new pipelines, but old ones found all over the country are also very dangerous, according to Kay. The resource threatened in her area is massive. The five Great Lakes together contain 20 percent of the planet’s fresh surface water, providing millions of people with drinking water, supporting a vibrant tourism industry, and offering bountiful fisheries.

Lying on the lake bottom are twin pipelines dating to the 1950s. Called Enbridge Line 5, they are part of the system that burst in 2010, dumping 840,000 gallons of oil into Talmadge Creek, leading into the Kalamazoo River, in Marshall, Michigan — the nation’s largest inland oil spill so far.

“Half of the pipelines in America predate our current environmental laws and protections,” said Payment. He was speaking to federal officials during meetings to discuss improving the government’s consultation with tribes on infrastructure projects.

“Aging pipelines with substandard welds and steel, old coating technology, or non-existent coating, and decades of corrosion are not subject to environmental or safety rules,” said Payment about Enbridge Line 5. “This is appalling.”

A leak in the straits would be devastating in good weather, but if it happened in winter and the damage were frozen under the ice for weeks or months, the effect on the sensitive environment and the regional economy would be unimaginable, says Kay.

Adding to area tribes’ concerns, figures from the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) show that detection systems and the employees running them do not discern most of what the agency calls “significant incidents.” Of the more than 4,000 significant incidents reported to PHMSA over six years, detection equipment recognized less than 10 percent, while the general public and techniques like ground and aerial patrols spotted the rest.

The Enbridge Line 5 danger impacts the tribes’ court-affirmed treaty right to fish within the waters of the Great Lakes, Payment told the federal officials. If natural resources are destroyed, that agreement is meaningless, he said: “To exercise the treaty right to fish, there have to be fish in the waters, and the fish have to be safe to eat. The US government does not have the right to give away our court-affirmed treaty rights to those who threaten them with environmental disaster.”

The damage would be to lifeways as well as to economies, adds Kay. “The treaty rights are at the heart of our tribe’s culture.”

Some may think of treaties as dusty documents that are no longer relevant. Not so, says Indian law attorney Rollie Wilson, with Fredericks Peebles & Morgan. They are contracts between governments and are enshrined as “the supreme law of the land” in Article 6 of the US Constitution.

“In these contracts, tribes reserved lands, rights, and resources and made agreements with what was a fledgling government,” says Wilson. “The tribes did not anticipate that the United States would not keep its word and keep coming back for more, or that as the United States gained power, it would unilaterally break treaties and impose agreements on tribes.”

Regardless, treaty rights are legally binding, as has been shown repeatedly in court, says Wilson. “Tribes exercise treaty rights every day, and they form the foundation of the government-to-government relationship between the United States and tribes.”

Memories of the Kalamazoo River accident are still fresh in the area. When the Michigan Petroleum Pipeline Task Force asked for public input for its 2015 report on Enbridge Line 5, the consensus was clear. Most respondents said to shut it down.

Enbridge procedures have changed for the better since 2010, says company spokesperson Ryan Duffy: “That event was transformational for us.” According to Duffy, Enbridge Line 5 is now monitored 24/7 from an “enhanced” control center that would automatically shut it down, should a break occur. That would presumably prevent what happened during the Kalamazoo River accident, when an Enbridge employee misread the signals and pumped even more oil through the broken Line 5, worsening the spill.

Duffy describes today’s inspection techniques as high-tech and continual with divers, robotic vehicles, and MRI-like scanning devices searching for corrosion and cracks. The company has resisted replacing the line. Duffy explains that it was “over-engineered” for its day with especially thick, enamel-coated steel.

The task force report casts doubt on this rosy assessment, noting that Enbridge makes public only its inspection conclusions, not its data. As a result, there is no way to verify the company’s assertions. Years of mussel-encrustation may have caused corrosion and added damaging weight to the pipes, which lacked sufficient anchors to the lake bottom “for an apparently extended period,” the report says.

The state task force is studying alternatives for the line, ranging from no change to replacing it to transporting its products by another method altogether. On January 4, 2017, the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians added another obstacle to the continued existence of Enbridge Line 5. It decided to no longer grant an easement for the line through its reservation in Wisconsin, explaining that “even a minor spill could prove to be disastrous.” Says Bad River tribal council member Dylan Jennings, “We are standing firm. We are not prepared to leave our future generations to deal with this pipeline and what could be the end of our way of life.”

Enbridge will be “taking some time” to review the Band’s decision before determining its next steps, says Duffy.

As this process inches forward, Kay continues to worry. Every day that Enbridge Line 5 remains in use is one day closer to disaster, she says. “It’s about our treaty rights,” she says, “and it’s about the water.”

Oak Flat, Arizona San Carlos Apache Nation

Sacred lands of the San Carlos Apache sit on the largest untapped copper deposit on the continent. Resolution Copper plans to extract the ore by blasting it from below and mining in through tunnels underground. Once the ore is removed, the earth above it will sink and create a crater nearly 1,000 feet deep and a mile across. (Photo: Janet Ward, NOAA)

Sacred lands of the San Carlos Apache sit on the largest untapped copper deposit on the continent. Resolution Copper plans to extract the ore by blasting it from below and mining in through tunnels underground. Once the ore is removed, the earth above it will sink and create a crater nearly 1,000 feet deep and a mile across. (Photo: Janet Ward, NOAA)

“Water is the giver of life in all tribes’ prayers,” explains Wendsler Nosie Sr., leader of the Apache Stronghold movement. “It is the blood of the world and unifies us all. These teachings go back to the beginning and have been passed from generation to generation, from family to family. They resonate from truth and are unchangeable.” The Apache Stronghold movement he leads is an effort to save Oak Flat, an Apache sacred landscape in Arizona.

Before Standing Rock, there was Oak Flat. Like Standing Rock, the encampment at Oak Flat is remote. Yet members from outside tribes, representatives from national and regional tribal coalitions, and non-Native supporters, including members of environmental and religious groups, have shown up in droves. The media has been attracted by dramatic supporting events, including participation in a Neil Young concert, a flash mob in Times Square, and a demonstration in Washington, D.C. “Movie stars, resisters tying themselves to heavy equipment, it all happened here,” says Nosie. The press coverage, in turn, has kept alive public interest in protecting the sacred place.

The Oak Flat controversy exploded in December 2014, when the Arizona congressional delegation slipped a land swap into the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015. The measure privatized a 2,400-acre traditional cultural landscape in the Tonto National Forest that has been revered by Apaches and other tribes since time immemorial. It then gave the tract to Resolution Copper Mining in return for approximately 5,000 acres of company land.

The British- and Australian-owned corporation plans to develop a giant copper mine that would, over its 60-year life span, turn the sacred site into a two-mile-wide hole in the ground, deplete and poison the area’s water supply, and produce a massive dump site of toxic mine waste, according to tribal and environmental opponents. “The profits will go overseas, and the United States will be left with the ugly results,” says Nosie.

To protect the site, Arizona Representative Raul Grijalva plans to resubmit the Save Oak Flat Act in the current congressional session, according to Adam Sarvana, communications director for Democrats on the House Natural Resources Committee. The act would strip the land swap out of the defense authorization, leaving the rest of the bill intact. (The last Congress did not act on the Oak Flat measure, so it must be re-introduced, Grijalva’s office explains.)

In another step forward, Oak Flat made it onto the National Register of Historic Places in March last year. This does not afford permanent protection but adds requirements to an already-detailed environmental review that is in the initial stages.

“We have created obstacles through the system,” says Nosie. But he and his allies are taking no chances. “We are also occupying this place. We will not allow the mine to come in.”

Tosawihi, Nevada Western Shoshone Nation

Joseph Holley of the Battle Mountain Band of the Te-Moak Western Shoshone surveys the land with his grandson, Julius. Holley’s band has taken the lead in protecting the Tosawihi Quarries, a tribal sacred site in north-central Nevada, from destruction by gold mining. The Shoshone have used the Tosawihi Quarries for more than 14,000 years, going there to collect their sacred white flint, fashion it into weapons and use it in ceremonies. (Photo: Joseph Zummo)

Joseph Holley of the Battle Mountain Band of the Te-Moak Western Shoshone surveys the land with his grandson, Julius. Holley’s band has taken the lead in protecting the Tosawihi Quarries, a tribal sacred site in north-central Nevada, from destruction by gold mining. The Shoshone have used the Tosawihi Quarries for more than 14,000 years, going there to collect their sacred white flint, fashion it into weapons and use it in ceremonies. (Photo: Joseph Zummo)

From time immemorial Western Shoshones have hunted, gathered, and participated in ceremonies in a rugged landscape in what is now northern Nevada.

“We arose here,” says medicine man Reggie Sope, of the Duckwater Shoshone Tribe, as he describes a careful, frugal lifeway that found bounty in these dry, rolling hills. His people hunted deer, rabbits, and other game and gathered wild onions and carrots and additional edibles. When the rabbit brush turned yellow in the fall, they trekked to forested mountains to pick pine nuts, a dietary staple they would roast and store for later use.

Called Tosawihi (dose-uh-wee), the place’s name is derived from that of a Western Shoshone band known for carrying razor-sharp blades made from the exceptionally hard flint found here. The stone has properties that assist traditional healers to this day.

This life and its seasonal round continued for millennia — until newcomers arrived looking for another kind of bounty. In the mid-19th century, silver and other valuable minerals were discovered in what, in 1864, would become the state of Nevada. The 1872 General Mining Law made it cheap and easy to stake out claims, driving up the population of settlers. To this day, a few hundred dollars will establish and hold a claim on public land that can be mined, with no royalties due to the federal government, unlike other extractive industries.

Sope’s people were pushed onto reservations despite an 1863 friendship treaty with the United States in which the tribes never ceded any land, including most of what is now the state of Nevada. It remains a bone of contention with the federal government.

The valley where the Western Shoshones are camped seems idyllic and untouched, but a foray out of it reveals much damage to the surrounding landscape. A horizontal cut scars the face of a hill used for eons for vision quests. The gouge was bulldozed during construction of a power line to support increased production at the gold mine that has taken a giant bite out of nearby hillsides. The power line also wiped out a centuries-old trail, where an ancestral healer walked, sang, and picked medicinal plants. People who needed care would hear his song and follow him.

Murray Sope (left) and Joseph Holley (right) help Reginald Sope, a healer from the Shoshone-Paiute tribe, place tarps over a ceremonial sweat-lodge frame in Tosawihi. (Photo: Joseph Zummo)

Murray Sope (left) and Joseph Holley (right) help Reginald Sope, a healer from the Shoshone-Paiute tribe, place tarps over a ceremonial sweat-lodge frame in Tosawihi. (Photo: Joseph Zummo)

Tosawihi sits on federal land administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). As such, national preservation and environmental laws protect Tosawihi. Western Shoshones have invoked these laws, telling courts that Tosawihi is a cultural landscape that is the product of many centuries of subtle interlocking practices — hunting, gathering, healing, and other aspects of traditional life. Portions of it have been determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. Tribal members claim that damage to Tosawihi could be avoided or minimized if the BLM followed federal law.

Court documents submitted by the BLM say the tribe is asking too much and call the tribal perspective the product of a “different worldview.” The agency has commissioned archaeological studies that have identified scattered locations on the landscape that can be considered for preservation under the law, while the rest may be subjected to mining-related destruction.

Tribal attorney Rollie Wilson says this reaction is typical and unfortunate. “Every day, tribes face federal agencies that do not listen to tribal concerns, do not ‘hear’ or know how to take into account what tribes are saying, do not take tribal consultation seriously, or are pressured to approve projects anyway.”

Joseph Holley, former chairman and now councilman of the Battle Mountain Band of the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone, learned about protecting tribal resources from watching his elders, and now his young grandsons stick close by, watching and learning.

As Holley walks around Tosawihi with the youngsters, Julius Holley finds an arrowhead made by a tribal forebear. He picks it up. “Just like mine!” he says, referring to a small arrow point his grandfather helped him shape the day before. A past of deep antiquity is vital and tangible in his young life. Intact landscapes, with sacred sites still present, offer these lessons, says Holley: “It is how our children learn who we are.”

Bristol Bay, Alaska Yup’ik, Dena’ina, and Alutiiq peoples

Sockeye swimming in Lake Iliamna in Knutson Bay near the community of Pedro Bay. Salmon and the lives and livelihoods that depend on it are at risk from the proposed Pebble Mine upstream and east of Bristol Bay. (Photo: Kimberly Williams)

Sockeye swimming in Lake Iliamna in Knutson Bay near the community of Pedro Bay. Salmon and the lives and livelihoods that depend on it are at risk from the proposed Pebble Mine upstream and east of Bristol Bay. (Photo: Kimberly Williams)

For Alaska Natives, tours of Nevada’s gigantic mines helped them learn how to protect their own critical resource, Bristol Bay. The Alaska tribal people needed to understand what they were facing when a mining consortium proposed placing what would be among the largest copper mines in North America, Pebble Mine, in the bay’s watershed. It is home to the world’s largest sockeye salmon fishery and one of its most prolific king salmon fisheries, providing thousands of jobs and pumping $1.5 billion into the US economy in a year, according to a 2010 University of Alaska study. The fishery also supports Alaska Native subsistence lifeways and cultures.

Kimberly Williams is the Yup’ik director of Nunamta Aulukestai (or “Caretakers of Our Lands” in Yup’ik), a tribal coalition in southeast Alaska that focuses on land-use issues. Williams says that when opposition to Pebble Mine gathered steam in 2004, tribal members realized they needed to learn how to effectively combat the project.

The environmental nonprofit Earthworks helped Williams and other tribal members reach out to Western Shoshones to learn about modern large-scale mining. Groups ranging in size from about eight to 15 and representing tribal communities around the bay traveled to Nevada starting in 2008; in 2012, a group visited Wendsler Nosie Sr. in Oak Flat, says Bonnie Gestring, an Earthworks staffer who accompanied the Alaskans.

In Nevada, the Alaska Natives toured mines and did flyovers. “Flying above large mines let people see the landscape-level environmental disturbance,” Gestring says. “And seeing the operations close-up on the ground familiarized them with the processes and their terminology, so they could understand when companies back home threw around technical language.”

The Alaska Natives also talked to the area’s indigenous communities, including the Elko Band of the Te-Moak Western Shoshone. “They could ask whether promises — about jobs or effects on the environment and subsistence lifeways, for example — had been kept,” says Gestring. The answer was generally no, she reports. The environmental impacts are crushing, the visitors to Nevada learned; moreover, modern-day mining is highly technical, with few jobs for local people seeking to break into the industry.

In early 2014, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released a report showing that building and operating Pebble Mine would likely damage the now-pristine Bristol Bay watershed. This would, in turn, reduce salmon habitat and affect additional fish and animal populations. The Native, salmon-based subsistence culture would suffer a blow as well, the EPA found: “The nutritional, social, and spiritual health of Alaska Natives would decline.”

Teresa Williams fishing for smelt at Lake Aleknagik. (Photo: Kimberly Williams)In the end, groups and individuals statewide — Native and non-Native — supported a ballot measure empowering the legislature to ban mines it determined harmful to wild salmon. This was despite opposition from industry groups like the Alaska Miners Association, which claimed the measure would politicize the mine-permitting process and stifle Alaska’s economy.

Teresa Williams fishing for smelt at Lake Aleknagik. (Photo: Kimberly Williams)In the end, groups and individuals statewide — Native and non-Native — supported a ballot measure empowering the legislature to ban mines it determined harmful to wild salmon. This was despite opposition from industry groups like the Alaska Miners Association, which claimed the measure would politicize the mine-permitting process and stifle Alaska’s economy.

“The initiative got 66 percent of the vote and won every precinct in Alaska, transcending party affiliation,” says Williams. “Everyone got it. Some families who own commercial boats have been coming here for 100 years; they get the importance of salmon. Sport fishermen who have waited their whole lives to get a 50-pound king salmon understand. We Native people understand, of course. The whole state gets it.”

This community support distinguishes the Bristol Bay movement from the one at Standing Rock, where much of the non-Native community does not support the tribe, observes Daniel Cheyette, attorney for Bristol Bay Native Corporation, the economic arm of tribes in the region. “Here in Alaska, the mining company will have a hard time moving forward, though they are persisting.”

Northern Dynasty Minerals, the primary corporation behind the mine, has sued the EPA, claiming environmental groups improperly influenced the agency’s report. The lawsuit is ongoing.

“Priceless” is how Alannah Hurley, the Yup’ik executive director of United Tribes of Bristol Bay, describes the bay and its watershed. “If our environment is destroyed, so are our cultures. We are fighting for who we are.”

“Our challenges,” Cheyette says, “are to keep reminding the public that this issue is not dead yet and to make it painfully obvious to the company that it has a long row to hoe on this issue.”

As at Tosawihi, Standing Rock, and other sites of Native resistance, the struggle involves young people working alongside their elders. Tribal members as young as 13 testified before the EPA when it was gathering information for its 2014 report, Williams says. “Issues like this keep arising, and our children need to be prepared. They may be fighting Pebble Mine or similar operations when they’re adults, and they understand that.”

“This involvement is expected of our young people,” says Hurley. The tribal consortium she heads advocates for the protection of the Yup’ik, Dena’ina, and Alutiiq way of life in Bristol Bay. “We all see it as part of our responsibility to our people and our lands.”

The important role Native youth play is evident all around Indian Country, says Nosie, of Oak Flat. “They have learned our spiritual teachings and carry them forward in a powerful way.”

Thurston County, Nebraska Omaha Tribe of Nebraska

Leading up to Memorial Day 2011, giant dams along the Missouri River were filled to the brim with water produced by torrential rains and higher-than-normal snowmelt. Among the farms, towns, and other entities downriver was the small, impoverished Omaha Tribe, where unemployment has hovered at about the 80 percent mark and a casino has been a major source of both revenue for the tribe and jobs for the few tribal members who have them.

Since the mid-20th century, the US Army Corps of Engineers has used dams large and small to reengineer the mighty Missouri and its tributaries. At first, the idea was to prevent flooding and facilitate navigation while providing electricity. Recent modifications include artificial sandbars to slow the river and make it more hospitable to recreation and wildlife.

In 2011, it was clear that the now-man-made waterway had become a fearsome Franken-river that its creator and master, the Corps, could no longer control. On May 27, the Corps told the Omaha Tribe it would release the Missouri’s swollen waters, and the tribe should expect the river’s level to rise quickly by as many as nine feet.

“Elders tell me that the river used to flood seasonally, which was not just controllable but a good thing, as it deposited new fertile soil along the bottomlands,” says Maurice Johnson, attorney general for the tribe. “However, 2011 felt more like a dam break.”

The damage up and down the river was disastrous. “The [Missouri’s] water no longer moves on through,” says Debbie Yarnell, spokesperson for law firm Polsinelli, which has sued the United States for the Corps’ decision. The suit was filed on behalf of nearly 400 plaintiffs, including the Omaha Tribe and farmers and businesses in five states the Missouri River traverses. “Thanks to the work done to slow the river, the water sits longer and does more damage,” says Yarnell.

Tribes are sovereign nations with government-to-government relationships with the United States. By law, federal agencies must consult with them when agency actions and policies would likely impact tribal resources. The agencies must then study the impacts and pursue the possibility of fixes, called “mitigation.”

However, agencies are not necessarily cooperative. In May 2011, on the Omaha reservation, the Corps’ consultation with the tribe was more along the lines of “ready or not, here it comes,” just days before the water hit. Former tribal chairman Vernon Miller reported this tragic lapse to federal officials attending one of the meetings the Obama administration called this past fall to discuss improving the government’s consultation with tribes. Questions about whether the Standing Rock Sioux were properly consulted during decision-making for the Dakota Access Pipeline precipitated the gatherings.

Historical photo from the Omaha tribe of Nebraska.

Historical photo from the Omaha tribe of Nebraska.

The Corps also failed to meaningfully assist the Omaha Tribe once it was clear they were facing a catastrophe. “I asked the Corps to come and help us evaluate what we could do,” recalls Omaha Tribe Emergency Management Director Carroll Webster. “They said they could send one guy for a few hours.” According to Corps spokesperson Eugene Pawlik, the agency is unable to respond to questions or provide comments because of the ongoing litigation.

Over the next several weeks, the community mobilized, with tribal employees and volunteers digging up land from elsewhere on the reservation and creating a berm to try to stem the flood. Despite their efforts, their homeland was inundated, including the casino and, with it, a financial mainstay. Destruction of farmland leased out for additional income meant more economic devastation.

Tribal members lost homes as well as jobs, but temporary trailer housing couldn’t be set up because the land stayed waterlogged for the better part of a year, says Richard Chilton, from the Omaha Tribal Historical Research Project. “People doubled up with other families or moved to Sioux City and other places until there was someplace here for them.”

Tradition sustained a blow as well since the flood damaged culturally important places. “We have sacred sites and burials throughout our land,” says Dennis Hastings, director of the research project. “This makes the whole landscape important to us. Since the flood, our elders go to pray at holy places, then leave. That’s all they can do. It hurts.”

When a community is so vulnerable, recovery takes a long time. With tribal and federal money, a new casino has been built on a higher foundation that should keep it above future flooding, according to Johnson. However, some land is lost forever as an income generator. “A flood like that scours away the topsoil,” says Webster. Five years later, he says, “parts of our reservation still can’t be farmed.”

As tough as the economic losses have been, the devastation of cultural places has been far worse, Johnson says. “It is not easy to recover from burials being washed away or sacred sites being damaged.”

Miller implored the federal officials at the consultation meetings to learn from these mistakes. Their decisions have huge impacts on tribal communities, he said, and consultations must be person-to-person, as well as government-to-government. A phone call or a letter warning of impending disaster is not enough, said Miller: Respect for tribal sovereignty demands more from the federal consultation process.

San Juan River, Utah Navajo Nation

Navajo river guide Markus Buck stands near Bluff, Utah, overlooking the San Juan River in 2010, several years before the waters ran orange as the result of an upstream EPA-triggered waste spill. (Photo: Heeb Christian / Alamy)

Navajo river guide Markus Buck stands near Bluff, Utah, overlooking the San Juan River in 2010, several years before the waters ran orange as the result of an upstream EPA-triggered waste spill. (Photo: Heeb Christian / Alamy)

The San Juan River is one of the nation’s latest Superfund sites. This past fall, it joined the 1,337 locations now on the US Environmental Protection Agency’s list of contaminated places. Nearly one-quarter of them are on Indian reservations, according to Indian Country Today Media Network, meaning that about 1 percent of the US population sustains 25 percent of the environmental and related cultural damage.

The San Juan River, which pours down into the Navajo reservation from the Rocky Mountains, turned a ghastly orange on August 5, 2015. This occurred as a result of EPA activities at the Gold King Mine in Colorado. The mine is one of many abandoned operations sitting by creeks whose waters eventually end up in the San Juan.

While attempting to draw off contaminated water, EPA-hired construction crews with heavy equipment triggered the collapse of a portion of the mine and a three-million-gallon blowout of toxic sludge laced with lead, mercury, and other heavy metals. Even worse, the agency didn’t tell the Navajo Nation that the poisons were headed for tribal members’ homes and farms until two days later. The EPA has taken responsibility for the disaster and has so far spent $29 million to clean it up.

Tribal member Mark Maryboy lives in Montezuma Creek, Utah, a tiny Navajo-reservation village on the San Juan River. “We still can’t drink the water or farm more than a year later. The spill brought Navajo farming and the area economy to a halt,” says Maryboy, a board member of Utah Diné Bikéyah, the grassroots group that in 2010 initiated the process of designating the Bear Ears National Monument.

The waters of the Animas River, a tributary of the San Juan River, ran orange within 24 hours of the spill in southwestern Colorado. (Photo: Riverhugger)In August 2016, an infuriated Navajo Nation sued the EPA, claiming that the damage to the river had caused anguish “akin to the loss of a loved one.” Tribal members worry about health consequences, and ceremonies that use sand and water from the river and pollen from once productive cornfields have been interrupted, says the Navajo brief. Tourists have stayed away, causing more economic pain.

The waters of the Animas River, a tributary of the San Juan River, ran orange within 24 hours of the spill in southwestern Colorado. (Photo: Riverhugger)In August 2016, an infuriated Navajo Nation sued the EPA, claiming that the damage to the river had caused anguish “akin to the loss of a loved one.” Tribal members worry about health consequences, and ceremonies that use sand and water from the river and pollen from once productive cornfields have been interrupted, says the Navajo brief. Tourists have stayed away, causing more economic pain.

In a statement supporting the tribe’s lawsuit, US Representative Ann Kirkpatrick (D-Ariz.) declared that for Navajos “water is life.” She reminded the EPA that the federal government holds Native lands in trust for tribes and their members and, as the trustee, has obligations to protect Native land and natural resources.

The Justice Department, which will defend the EPA, has not yet responded to the complaint, according to attorney Moez Kaba, who is part of the team representing the Navajo Nation.

Resource extraction is rarely advantageous for anyone outside the corporations that own the mines and oil wells, Maryboy says. “Local communities don’t benefit when resources are taken out of the ground. We’re just left with the mess.”

The EPA has announced that the river is greatly improved and “trending” toward its pre-spill condition. “Navajo people don’t believe them,” says Maryboy. “We have been exposed to dangerous materials before, including uranium from Cold-War era mining in this area, and have cancer and other diseases that result from such exposures.” Navajos worked in the mines for four decades without safety gear; then, once the mines were closed, it took nearly three decades more for the EPA to begin removing the toxins. The agency started with a small program in 2008 and recently began a one-billion-dollar cleanup, funded by a settlement with the mine operator.

“In the minds of many Navajos, agencies like the EPA and corporations are essentially the same, and they don’t trust them,” says Maryboy. “Our goal now is to be sure that nothing like this happens again.”

Columbia River Gorge, North Oregon BorderYakama Nation, Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs (Warm Springs, Wasco and Paiute)

The Columbia River Gorge sits between Cascade Locks, Oregon, and Goldendale, Washington, where Nestlé has been trying to identify a spring from which it could draw off and bottle water. (Image: Still from a Story of Stuff Productions video)“When the tribes stepped forward to talk about their treaty rights, as well as the human rights issues involved with losing water, it was incredibly powerful,” says Julia DeGraw, Northwest senior organizer for Food & Water Watch.

The Columbia River Gorge sits between Cascade Locks, Oregon, and Goldendale, Washington, where Nestlé has been trying to identify a spring from which it could draw off and bottle water. (Image: Still from a Story of Stuff Productions video)“When the tribes stepped forward to talk about their treaty rights, as well as the human rights issues involved with losing water, it was incredibly powerful,” says Julia DeGraw, Northwest senior organizer for Food & Water Watch.

Since 2009, DeGraw and a grassroots group of local landowners, businesspeople, and others have been seeking to stop Nestlé Waters North America from “spring shopping” in rural Oregon. The corporation has been trying to identify a spring where it could draw off and bottle water that would be sold at a premium because of its pristine origins.

The first place Nestlé tried to set up shop was bucolic Oxbow Spring, in the town of Cascade Locks, Oregon. The company claimed it had done hydrological, air quality, and other studies and found the project would be sustainable and have little environmental impact. In return, the town could get around 50 jobs, Nestlé Waters said.

After a severe drought heightened local fears about selling off water, residents of the surrounding county, including the tribal members, mobilized. They held rallies and wrote a ballot measure that would make it illegal to bottle water in the county. They knocked on doors and attended events to gather support for the measure. The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs chimed in, decrying the bottling project, saying it had moved forward without proper tribal consultation and public review. Warm Springs tribal member Annie Leonard fasted.

In May 2016, 69 percent of the county voted to approve the measure and nix the Nestlé project. The ballot measure wasn’t binding on the town, though, which appeared to be still interested in moving forward.

In a sternly worded letter, the Yakama Nation warned Cascade Locks that drawing off the water would “undermine our culture and threaten our treaty-reserved rights.” The tribe explained its duty to protect “those resources that cannot speak for themselves, including our water.” The letter went on to explain the reciprocity between the tribe, as a caretaker, and the water, which nurtures the natural resources the tribe needs for its existence — timber, fish, animals, and more.

Yakama Nation Chairman JoDe Goudy and his wife, Maranda Goudy, and Anna Mae Leonard of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, at a rally at the Oregon State Capitol opposing plans for a Nestlé water-bottling plant in the Columbia River Gorge. (Photo: Food and Water Watch)

Yakama Nation Chairman JoDe Goudy and his wife, Maranda Goudy, and Anna Mae Leonard of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, at a rally at the Oregon State Capitol opposing plans for a Nestlé water-bottling plant in the Columbia River Gorge. (Photo: Food and Water Watch)

Since then, Nestlé Waters has begun talking to the nearby town of Goldendale, Washington as well. “Nestlé has suggested to us that there will be a $50 million bottling plant and jobs, but the public has come out with a lot of positions, [both] pro and con,” said City Administrator Larry Bellamy. “So we’re going to gather information about what they’re going to do, the amount of water they want, what spring they’ll use, and more. No one is signing onto anything. We’re at less than square one.”

The tribes are standing fast. During a November 2016 Goldendale city council meeting, the Goldendale Sentinel reported, Yakama general counsel Ethan Jones called threats to tribal water rights “genocide” and vowed “we will do whatever it takes” to stop them.

“All of this is about protecting the earth and focusing on what we value as tribal societies,” says Carina Miller, from the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. Again, youth are important to the effort. “In the past, it was so difficult to think that tribes could have a real voice. Now, our younger generation is empowered because of all the healing work that has been done and all the conversations we have had about the historical trauma that has impacted us generation after generation.”

Miller foresaw additional rallies against the Nestlé project, as well as against any additional projects that tribes see as destructive. “We must protect our culture and language any way we can.”

And Native people must safeguard the water, Miller adds, echoing the language that came out of Standing Rock and reverberates throughout Indian Country. “Water is the most sacred thing.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.