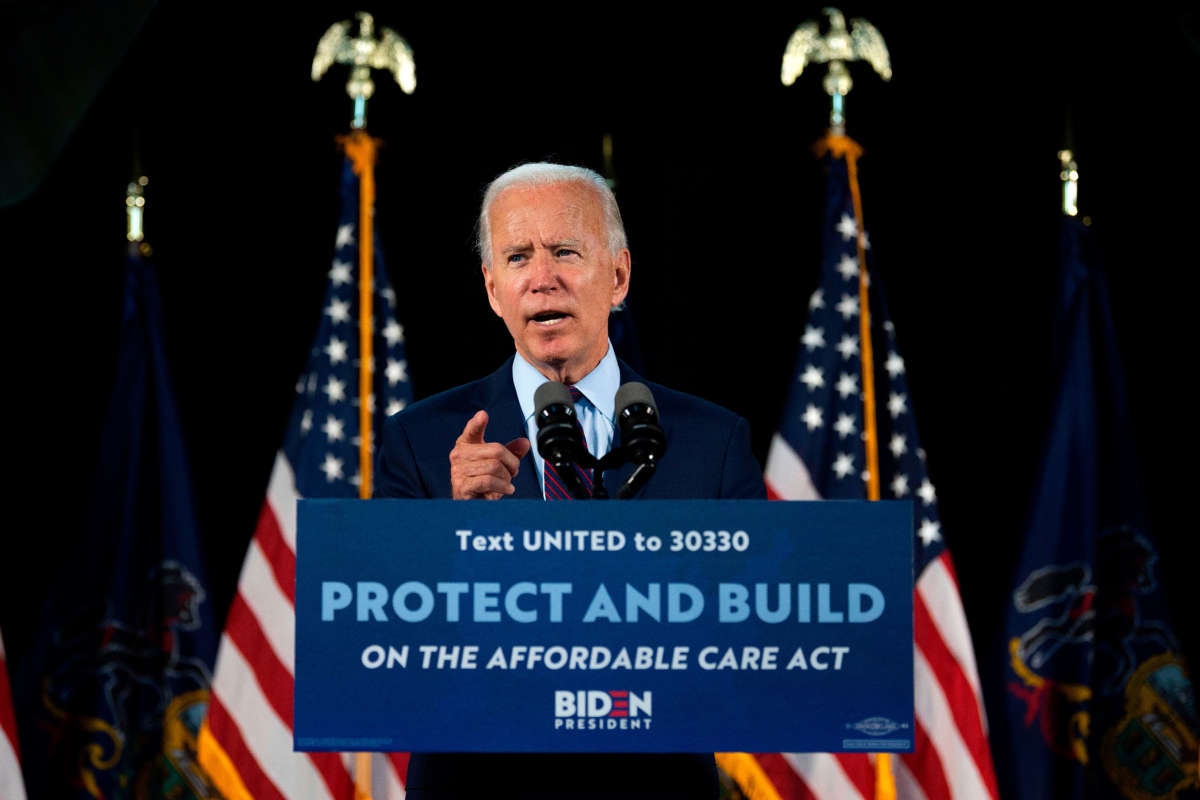

Last year, on the campaign trail, President Joe Biden released a $750 billion, 10-year plan designed to massively expand the reach of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). It would create a public option, allow undocumented immigrants to buy into that public option, lower the age at which Americans become eligible for Medicare, take Medicaid expansion into the 12 Republican heartland states that chose not to expand it themselves, and permit Americans to buy prescription drugs from overseas at a cheaper cost.

Since assuming office, such sweeping health care ambitions have taken a back-burner to getting COVID relief passed, to developing a large-scale infrastructure plan, and to initiating a reset on environmental policy. But that doesn’t mean there is less urgency to lock into place big-picture health insurance changes. After all, the Biden administration inherited a barn-on-fire situation from the previous president, and we are still in the middle of a pandemic.

There are, in 2021, more than 2 million low-income American adults who live in states that didn’t expand Medicaid, and who can’t access private insurance on the exchanges because their income is deemed too low to qualify for tax credits. Of these 2 million, more than a third live in Texas. All told, by the middle of 2020, at the height of the pandemic, about 30 million non-elderly Americans remained without insurance. That’s down from 48 million in 2010, but it’s up from 28 million at the end of Barack Obama’s presidency. The increased numbers of uninsured in the years from 2017 to now are the clear result of former President Donald Trump’s effort to eviscerate his predecessor’s central legislative accomplishment and make it ever-harder for Americans to enroll in the subsidized insurance plans.

From 2017 through to January 20, 2021, health care advocates had to play defense pretty much all the time. From day one of his administration, Trump, with the full backing of most of the GOP, had the ACA, known more popularly as Obamacare, in his sights. In his first months in office, the Senate came within one vote of rolling back the legislation that had created the ACA. It was that one vote, cast by an ailing Sen. John McCain against dismantling the ACA, that fueled Trump’s loathing for, and mockery of, the dying Arizonan.

After Republicans failed in Congress to repeal the ACA, Trump sought to kill it by a thousand cuts: to make it harder for patients to enroll on health care exchanges, to limit Medicaid expansion, to cut funding for outreach campaigns to educate people on how to enroll. Finally, having failed to destroy the program this way, Trump’s administration decided to side with Texas and other GOP states in their Hail-Mary lawsuit attempting to have the entire thing declared unconstitutional.

That case was heard by the Supreme Court last year, and a decision on it should come down in the next few months. Given the extraordinarily conservative composition of today’s Supreme Court, it’s at least possible — though perhaps not likely, given previous rulings on the issue — that they’ll end up taking a judicial axe to the entire project.

Which is why it’s all the more vital that, in the interim, state and federal officials work to expand the ACA as rapidly as possible. After all, the more people are covered, and the more the ACA is seen to be an indispensable, life-saving pillar of the country’s health care delivery edifice, the harder it will be to pull the rug out from under it. Given that neither party seems likely to push for a more rational, more equitable universal health care system anytime soon, ironing out the kinks in the ACA and expanding its reach seem to represent the best short-term path toward near-universal coverage.

An ACA expansion would inevitably still fall short of a truly universal, single-payer system, and it would do little to address systemic problems such as over-billing and the profiteering of middle-men institutions, which go hand in hand with for-profit insurance systems as a primary delivery system for medical services. But it would, nevertheless, bring additional millions of uninsured Americans under health care umbrellas.

Earlier this year, the Biden administration extended the special enrollment period for the ACA insurance exchange through August 15 of this year, arguing that, because of the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic, it was imperative to make it as easy as possible for Americans to find affordable health insurance coverage. California and other states with their own exchanges also followed suit in keeping enrollment open.

The result of this has been encouraging: In the first weeks of the special enrollment period, well over 200,000 people signed up for coverage, eclipsing, by orders of magnitude, the numbers from the first weeks of earlier special enrollments. Hundreds of thousands more have begun the application process to get insurance via these exchanges; and additional tens of thousands have been declared eligible for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Moreover, the latest COVID relief package in Congress freed up billions of dollars to increase subsidies to lower-income people buying coverage on the state exchanges. In many cases, premiums for people around the country will be cut in half. And in some states, funds will be used to essentially eliminate premiums for poorer residents. In California’s case, for example, this means an additional $3 billion for subsidies. As a result, come May, some low-income Californians will be paying only $1 per month for their health insurance. Hoping to get more Californians to take up insurance through the exchange, the state will spend $20 million on an outreach and advertising campaign promoting the new lower rates.

For a state that has already managed to cut its uninsured population from about 17 percent down to roughly 7 percent, all of this is a huge deal. Combine it with the ongoing efforts to expand Medi-Cal to cover all low-income undocumented adults, and one sees a road-map being drawn in California that would, over the coming years, get the state as close to having universal coverage as possible given the nature of the current U.S. health insurance system.

Where California goes on health care coverage, the nation might one day follow – especially with California’s former Attorney General Xavier Becerra now in charge of the Department of Health and Human Services, and pushing an emphasis on health equity and public health readiness. Already, California has self-funded Medicaid expansion to include young undocumented adults up to the age of 26. Quite possibly, later this year the state may expand the expansion to include a much larger proportion of the undocumented population. This jibes well with the proposals then-candidate Biden put out on the campaign trail. Hopefully, once California paves the way, Biden and the Democratically controlled Congress will follow through on their health care commitments at a federal level too.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.