Marcus Butler stands outside his childhood home. It’s a squat single-story bungalow with white aluminum siding behind a short metal gate.

The stocky 62-year-old Army veteran greets old friends who drive by. When Butler was young, the front yard of 1539 W. 69th St. in South Los Angeles was covered in rosebushes grown by his mother. Today, it’s overgrown with crabgrass, the last living rosebush about to expire.

In the past five years, the house has passed through the hands of five confidants of President Donald Trump on its journey from homeownership to rental, from single-family house to investment commodity, from a symbol of faith in the future for a family that moved west to a dilapidated rental for a terminal cancer patient.

“I would have wanted to pass the house on,” Butler said. “That’s what we were taught when we were younger. You get a house, you pay for it, then you pass it on to the next child or grandchild, try to keep the house in the family.”

Marcus Butler lives in an apartment in Los Angeles’ Baldwin Hills neighborhood with his wife, adult son and baby granddaughter. For nearly five decades, Butler’s family had owned a home in South Los Angeles, but a bank run by Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin foreclosed on it after Marcus’ mother died in 2012. (Photo: Stuart Palley for Reveal)

Marcus Butler lives in an apartment in Los Angeles’ Baldwin Hills neighborhood with his wife, adult son and baby granddaughter. For nearly five decades, Butler’s family had owned a home in South Los Angeles, but a bank run by Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin foreclosed on it after Marcus’ mother died in 2012. (Photo: Stuart Palley for Reveal)

The Butler family owned this home for nearly five decades. But after Marcus’ mother died in 2012, the house became a pawn in a real estate game that last year helped plunge America’s homeownership rate to its lowest level since 1965.

While soaring home prices, stagnating wages and tough loan requirements surely have contributed to historically low homeownership, the story of this modest bungalow suggests a more deliberate force at work, one commandeered by a cabal of Trump’s closest associates.

It was foreclosed on by a bank run by Steve Mnuchin, now Trump’s treasury secretary, and Joseph Otting, whom Trump nominated to be America’s chief bank regulator. The bungalow was then sold on the courthouse steps to a company created by Tom Barrack, a Southern California real estate mogul and one of Trump’s oldest friends.

Eventually, the home was bundled, along with more than 3,000 other single-family homes, into a $514 million mortgage-backed security, which holds the deed to the house. The company that created that security, JPMorgan Chase & Co., is led by Jamie Dimon, vice chairman of an economic advisory panel that met regularly with Trump until it disbanded last month in the wake of the president’s comments blaming “both sides” for violence at an alt-right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Also last month, a firm founded by the chairman of that same economic panel, Stephen Schwarzman, announced that it was merging with the company Barrack founded — creating the largest single-family-home rental company in America.

The result is that the bungalow on West 69th, like tens of thousands of others touched by these Trump cronies, is now off the market for working-class and first-time homebuyers. It bears witness to a grim reality of housing policy under America’s first real estate magnate president.

Nearly eight months into the Trump presidency, the signs point in one direction: The administration no longer promotes homeownership as key to the American dream. Instead, it seems, Americans should be satisfied to simply live in a home; in some cases, one that enriched the president’s inner circle. Now with their man in power, these confidants of the president are exploring ways to put taxpayers on the hook should their financial schemes fail.

Trump himself encouraged this sort of behavior, cheering a potential crash in 2006. “I sort of hope that happens,” he said in a seminar for Trump University, his now-defunct real estate seminar program. “People like me will go in and buy like crazy.”

***

On an early morning in April, Shawn Pruett answered the door of the Butler family’s old home. Gaunt and dying of cancer at 46, he was wearing a T-shirt and boxers, so weak he could barely restrain his 70-pound Labrador, Wilson.

Shawn Pruett, shown in April, rented the Butler family home in South Los Angeles after it was sold to a company founded by Tom Barrack, a close friend of President Donald Trump’s. Pruett died of cancer in August. (Photo: Stuart Palley for Reveal)Pruett used to own a house on a small Texas farm, where he kept a coop full of chickens, two donkeys and three goats.

Shawn Pruett, shown in April, rented the Butler family home in South Los Angeles after it was sold to a company founded by Tom Barrack, a close friend of President Donald Trump’s. Pruett died of cancer in August. (Photo: Stuart Palley for Reveal)Pruett used to own a house on a small Texas farm, where he kept a coop full of chickens, two donkeys and three goats.

“I had a wonderful garden with some beautiful flowers that I planted,” he said. He planned to take up beekeeping, “but that never happened” — because he got sick: AIDS, then lymphoma.

In 2013, Pruett sold the farm for $98,000 and headed out West, hoping treatment at the University of California, Los Angeles hospital could extend his life.

He found the house on Craigslist and rented it sight unseen. By April, when a reporter with Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting visited, the house was crammed with art from an antique store Pruett once owned. The carpet was frayed. The property’s winning attribute for Pruett was that it allowed pets and had a backyard where his dogs — Wilson and four dachshunds — could play.

“That’s why we’re here,” he said, swinging the screen door open for them.

He had no idea it was owned by a new breed of corporate landlord.

The Corporate Landlord

Tom Barrack started buying houses in 2012, the year Beulah Butler died. Before long, the company he founded — which became Colony Starwood Homes — had scooped up and rented out more than 30,000 single-family homes across 10 states. Most of them were foreclosures lost by families during the housing bust.

“It’s the greatest thing I’ve ever done,” Barrack told a real estate conference in 2012.

Tall and tan, with a vineyard in Santa Barbara and a passion for surfing, Barrack is the archetype of a Southern California billionaire. Although he’s dabbled in Hollywood — once flipping the Miramax film studio from Disney to a group of Qatari investors — his main business always has been real estate, often buying distressed assets, such as Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch.

Barrack and Trump have been friends and business partners for decades, starting in the 1980s when Barrack facilitated Trump’s purchase of New York’s famed Plaza Hotel.

When Trump decided to run for president, Barrack was among the first business leaders to endorse him. Barrack ultimately raised about $130 million to help his friend: nearly $23 million for a pro-Trump super political action committee and another $107 million for the inauguration. Barrack introduced Ivanka Trump at the Republican National Convention and stood behind the New York tycoon as he took the oath of office.

Since the campaign, Barrack has emerged as a Zelig-like figure in Trump’s inner circle, helping the family at critical moments: finding a lawyer to help Trump defend himself in the Trump University fraud case, introducing Trump to fixer Paul Manafort and even granting a break to Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, when Kushner’s Manhattan office tower teetered on the brink of foreclosure.

Although Barrack declined to talk to Reveal, another longtime Trump confidant, Roger Stone, said Barrack could have taken on a more official role in the administration, such as treasury secretary.

“I don’t think he has any belly for public service,” Stone said of Barrack, who turned 70 in April.

Public service doesn’t pay as well, either. In the private sector, Barrack has continued to profit off the housing bust. In June — one day after an exposé by Reveal found rampant evictions and poor conditions in many homes owned by the company he founded — Barrack sold his stock in Colony Starwood Homes and resigned from its board.

His final stock sale alone was worth $135 million.

Dying and Facing a Rent Increase

Barrack’s departure did not change a central feature of the company, which has since announced a merger with Dallas-based Invitation Homesthat would create the largest owner of single-family homes in the nation, 82,000 houses strong. Like Colony, Invitation Homes was created by a private equity fund, the Blackstone Group, led by Stephen Schwarzman.

The company remains a far-removed, out-of-state landlord interested solely in profit. Unlike mom-and-pop landlords, who know their tenants, it is a distant publicly traded company. Its primary interest: maximizing profits from properties such as the bungalow at 1539 W. 69th St. and tenants such as Shawn Pruett.

The company’s standard lease agreement, which Pruett signed, is a case in point. It required him to pay for, and manage, a host of repairs that are normally the landlord’s responsibility — including sewer blockages and broken glass “regardless of cause.”

But back in April, Pruett didn’t have the energy or means to stay on top of repairs. After four rounds of chemotherapy, UCLA doctors had told him that he didn’t have much more time.

“I’m beyond helping at this point,” he said one Sunday in his living room, surrounded by cigarette butts, with the shades drawn and the television on mute. “Basically, you’re just watching me die. I know that sounds macabre, but it’s true.”

Shawn Pruett — shown with his Labrador, Wilson, and one of his four dachshunds — said the corporate landlord that owns his home, Starwood Waypoint Homes, raised his rent every year. His lease agreement required him to pay for and manage repairs that are normally the landlord’s responsibility. (Photo: Stuart Palley for Reveal)

Shawn Pruett — shown with his Labrador, Wilson, and one of his four dachshunds — said the corporate landlord that owns his home, Starwood Waypoint Homes, raised his rent every year. His lease agreement required him to pay for and manage repairs that are normally the landlord’s responsibility. (Photo: Stuart Palley for Reveal)

Inside, the home was run down. Records from the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety show that no work permits had been taken out since Barrack’s company bought the property four years earlier.

Fronds from a palm tree on the neighbor’s property were tangled in the electrical wire that leads to the house — a potential fire hazard. But the lease Pruett signed made fixing that his responsibility, too.

And he said he didn’t have the money. In the kitchen, his cupboards were filled with Campbell’s soup and Jif peanut butter he got from the local food bank. Pruett lived on a fixed income, federal disability insurance.

Colony had raised his rent every year since he moved in. Another rent increase was due at the end of August. Pruett died first, on Aug. 2.

“Greed; it’s just greed,” Pruett said in April. “You’d think you’d be praised and rewarded for paying your rent on time and not having any problems and all that, but instead, they raise your rent and punish you, basically, for being a good tenant.”

The company declined to discuss Pruett’s case. In a written statement, Colony said it provides an “exceptional living experience through the highest servicing standards.” Invitation Homes sent a similar statement, saying the merger would “benefit our residents and the communities and neighborhoods in which we do business.” In Starwood Waypoint Homes’ most recent shareholder prospectus, however, company executives touted raising rents and spending less on maintenance.

That’s what happens when a house becomes a commodity instead of a home.

A House That Dreams Are Made of

It wasn’t so long ago that the bungalow represented a family’s hopes and dreams.

When Beulah and M.L. Butler drove from the small town of McComb, Mississippi, to the big city of Los Angeles in 1948, they were among the hundreds of thousands of African Americans who came West looking for economic opportunity and an escape from the Jim Crow South.

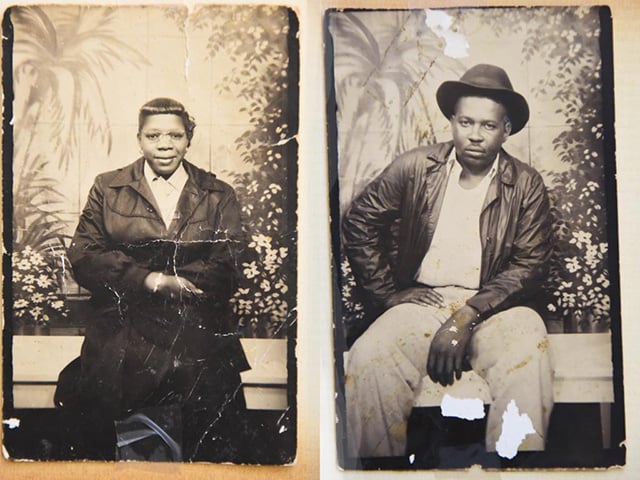

Undated portraits of Beulah and M.L. Butler were taken when they still lived in McComb, Miss. In 1948, the couple drove from the Jim Crow South to Los Angeles. Fifteen years later, they would buy a home on West 69th Street. (Photo: Courtesy of the Butler family)

Undated portraits of Beulah and M.L. Butler were taken when they still lived in McComb, Miss. In 1948, the couple drove from the Jim Crow South to Los Angeles. Fifteen years later, they would buy a home on West 69th Street. (Photo: Courtesy of the Butler family)

M.L. landed a job at the post office, while Beulah went to work as a maid, taking the bus daily from her home near the city center to cook and clean for a woman in Pacific Palisades. Six years after they arrived, Beulah gave birth to Marcus. The couple worked hard, and in 1963, when Marcus was 10, they bought their first home — the bungalow on West 69th Street.

The redwood-framed house had two bedrooms, one bathroom and an apricot tree out back. It was built in 1923, the same year news baron Harry Chandler put up the famous Hollywood sign.

For four decades, it had been owned by a succession of white, working-class homeowners. In 1960, three years before the Butler family bought it, then-owners Barney and Frances Barnett covered the stucco exterior with the white aluminum siding that still sheaths it today.

The house wasn’t much, Marcus said, but “it was ours.”

“We were one of the first black families in the neighborhood,” he said. Soon they were joined by others.

When he turned 18, Marcus joined the Army and decamped to Texas, where he helped coordinate logistics for war in Vietnam. When he returned three years later, the Crips and Bloods were fighting in the streets. The neighborhood kids no longer played at Harvard Park. Police-community relations, never great, deteriorated.

In 1992, when riots broke out after the acquittal of four Los Angeles police officers for the videotaped beating of Rodney King, the epicenter was five blocks away. At the corner of Florence and Normandie avenues, a mob attacked dozens of motorists, including Reginald Denny, a white truck driver.

Through it all, the Butler family stayed in the bungalow, making mortgage payments.

Losing the Dream

Forty-five years after the Butlers moved from Mississippi, the home finally was paid off. By then, Marcus’ father, M.L., had died.

Beulah returned to school and launched a career in the defense industry, working as an electrician for the Hughes Aircraft Co. and later Raytheon Co. She retired with a pension and a home in the clear. Then things started to go wrong. Marcus put it simply: “She had a gambling problem.”

Beulah loved the slots, and in retirement, she was constantly gone to Las Vegas or Southern California’s American Indian casinos. Sometimes she drove her Buick Regal. Other times, she boarded a special casino bus that stopped in the parking lot of Ralphs grocery store at the corner of Western and Manchester avenues. Her favorite casino was the former Binion’s Horseshoe, a frontier-themed affair with low ceilings and velvet wallpaper, away from the Strip.

In their weekly lunches at Red Lobster and Olive Garden, Marcus reprimanded his mother, warning her of the dangers of gambling. But as the years dragged on, Beulah continued to play the slots, even as her mental faculties slipped.

“She was struggling with dementia,” said Marcus’ daughter, Jessica Butler. “She was so used to being independent, but she didn’t remember anything. She would forget to wash. She would forget to shower.”

Beulah also suffered from kidney failure, which required dialysis three days a week. Two years before Beulah’s death at 82, Jessica, then 27, moved into the bungalow. She had just graduated from Humboldt State University with a degree in social work and agreed to take care of her grandmother full time.

It was then that Jessica spotted the mail from Financial Freedom Senior Funding Corp. Soon she would learn that in 2007, at the height of the real estate bubble, her grandmother had taken out a reverse mortgage, which allowed her to take up to $544,000 out of the family home, including fees and compound interest. Public records show the loan came with an adjustable interest rate that topped out at 16.6 percent.

Enter Steve Mnuchin

The financial tsunami that took out Lehman Brothers and Washington Mutual in 2008 also led to the collapse of Financial Freedom’s parent company, IndyMac. The U.S. government’s Office of Thrift Supervision closed the company and turned over conservatorship to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. When IndyMac failed, it had $32 billion in assets, making its collapse one of the largest in American history.

Eight months later, the FDIC put IndyMac up for auction and sold it for $13.9 billion. The buyer? An investment group led by hedge fund manager Steve Mnuchin.

He renamed it OneWest Bank and made himself chairman and CEO.

Like Tom Barrack, Mnuchin is a Trump confidant who’s worked in Hollywood. His executive producer credits include “Mad Max: Fury Road” and “The Lego Movie.”

Last May, after Trump won the Indiana primary, all but clinching the Republican nomination, he tapped Mnuchin as his campaign finance chief. Mnuchin’s selection surprised many observers because the former Goldman Sachs investment banker had a long history of donating to Democrats, including Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton.

But in an interview with Bloomberg, Mnuchin cited his personal relationship with Trump. The 54-year-old financier said he and Trump had known each other for 15 years and had done business together. According to The Hollywood Reporter, Mnuchin once invested in a Trump property near Honolulu’s Waikiki Beach. In 2007, two years before he bought IndyMac, Mnuchin tried, and failed, to buy Trump’s casino properties in New Jersey.

As campaign finance chief, one of Mnuchin’s first acts was to announce a major fundraising push. The launch would be at Barrack’s walled estate on San Vicente Boulevard in Santa Monica, 15 miles from the former Butler family bungalow on West 69th Street.

After Trump beat Clinton, he nominated Mnuchin to be his treasury secretary. Mnuchin added a $12.6 million Washington, DC, mansion to a personal real estate portfolio that also includes a sprawling 21,000-square-foot Bel Air estate and a Park Avenue apartment in New York.

When Mnuchin married for the third time in June, Barrack and Trump both attended the black-tie wedding in Washington, DC.

The “Foreclosure King”

As the head of OneWest, Mnuchin was famously aggressive. He earned the nickname “Foreclosure King” for the speed with which OneWest seized the homes of his borrowers. Many, like Beulah Butler’s South Los Angeles bungalow, were Southern California homes with reverse mortgages. Others were homes purchased with subprime adjustable-rate loans. In one infamous case, the company’s successor, with Mnuchin heading up the board, threatened to take the house of a 90-year-old woman for failing to pay 27 cents.

Documents obtained from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development show Financial Freedom foreclosed on at least 16,000 homes between spring 2009, when it was acquired by OneWest, and the end of 2015.

Although its share of the reverse mortgage market was 17 percent, it was responsible for nearly 40 percent of reverse mortgage foreclosures. The bank currently is being investigated by HUD for discriminating against nonwhite borrowers in its lending.

In May, it settled a federal fraud complaint for $89 million. The Justice Department alleged that the company had bilked taxpayers for excess insurance payments on the federally insured mortgages.

By then, Mnuchin was Trump’s treasury secretary. During his Senate confirmation hearing in January, Mnuchin bristled at the characterization that he profited from other people’s pain.

“Since I was first nominated to serve as treasury secretary, I have been maligned as taking advantage of others’ hardships in order to earn a buck,” he told lawmakers. “Nothing could be further from the truth.”

Foreclosing on Women and Orphans

In June, three weeks after Financial Freedom paid to settle the federal fraud charges, Trump announced he was appointing Joseph Otting, a former executive of the company’s owner, OneWest, as comptroller of the currency — the nation’s top banking regulator.

When Otting was its board chairman, the California Chamber of Commerce successfully killed legislation that would have made it more difficult for banks to foreclose on widows, orphans and other relatives. If confirmed by the Senate, he would be charged with making sure banks provide fair credit opportunities to low-income borrowers and people of color.

After Beulah Butler died in 2012, OneWest foreclosed on the home — but not before it sent the dead woman a letter demanding more than $326,000. Reverse mortgage analysts told Reveal that much of it was likely money she never actually saw — soaked up in fees and compound interest.

There was no way the family could come up with enough money to save the house, so Jessica Butler packed up her grandmother’s belongings and rented an apartment in the nearby Crenshaw neighborhood.

The bungalow sat empty for nearly a year. Squatters moved in. Marcus drove by, called the police.

“He was just heartbroken,” Jessica said.

On April 13, 2013, when OneWest sold the Butler family home outside the county courthouse, the buyer was Colony — the real estate company founded by Barrack.

The purchase price was $180,000 — about half what OneWest had demanded from the Butler family.

Four months later, Shawn Pruett signed a lease and moved in. But collecting rent from tenants is only one way that Barrack made money. Another involved bundling the properties into financial products reminiscent of the lead-up to the Great Recession.

And for that, Barrack teamed up with a Wall Street banker who met regularly with Trump at the White House.

The Wall Street Banker

Jamie Dimon is the chairman, president and chief executive officer of JPMorgan Chase. Like most elite Wall Street bankers, he owns two homes in New York: a luxury condominium on Manhattan’s Upper East Side and a sprawling estate in Westchester County, which Zillow says is worth $17 million. A prominent Democrat, Dimon quickly found a home in the new administration as vice chairman of the White House Strategic and Policy Forum, until it disbanded in August.

Like other Trump associates, Dimon has been betting big against middle-class homeownership. In 2014, JPMorgan Chase began pioneering a new type of mortgage-backed security on rental homes owned by corporate landlords.

Under the terms of these deals, tens of thousands of homes once owned by families have been bundled and leveraged. After that, those bundles are cut into pieces and sold to investors.

To date, JPMorgan Chase has extended $3.2 billion in credit to the company founded by Barrack. Its mortgage-backed securities now cover more than 20,000 of the company’s homes.

The first of these deals included the Butler family’s bungalow in South Los Angeles, along with 3,398 others spread across seven states. Under the terms of the deal, JPMorgan gave Colony $514 million in cash.

The deals present a win-win for Barrack and his investors. They can pull money out of the homes, enriching the company’s directors and shareholders — all while tenants pay back the debt to JPMorgan Chase through their monthly rent checks.

“That’s good for them, but it’s horrible for the future of equity and the middle class,” said Jesus Hernandez, a licensed real estate agent who teaches sociology at the University of California, Davis.

“Historically, homeownership has been the key to generational accumulation of wealth, and now all that wealth is going to corporate landlords,” he said.

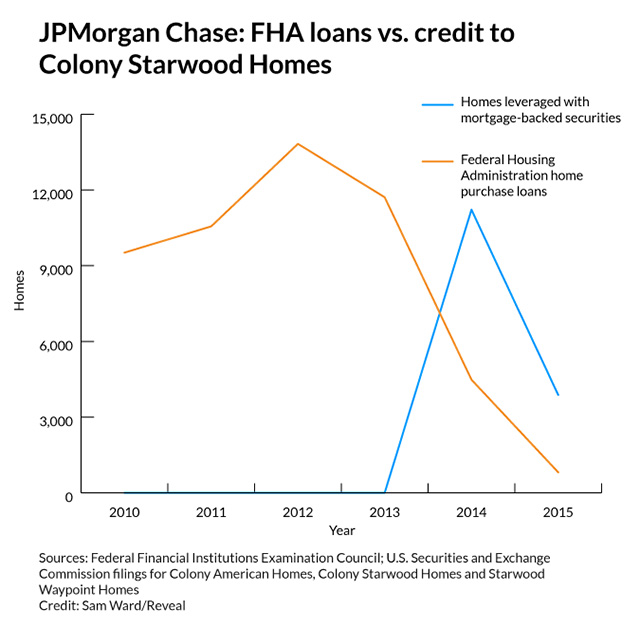

And at the same time Dimon’s bank was bundling homes with Colony, the bank’s lending to working-class homebuyers dried up. From 2010 to 2015, government data shows the number of Federal Housing Administration-backed home loans originated by JPMorgan Chase dropped by 91 percent.

JPMorgan Chase extended four times as much credit to Barrack’s rental home empire in 2015 as it did to government-backed loans to working-class Americans. Barrack’s company was able to pull money out of nearly 4,000 homes by creating mortgage-backed securities, while the bank made just 813 loans through the Federal Housing Administration.

Changing the Rules

On June 12, a week after Otting’s nomination by Trump, Mnuchin releaseda 149-page report recommending a wholesale weakening of consumer protections enacted since the housing bust.

Among the changes proposed by Mnuchin: Allow the president to fire the head of the currently independent Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, remove data and details of consumer complaints from the bureau’s website, and loosen reporting requirements on banks that track whether they are discriminating against borrowers because of their race.

The report was but one of the administration’s actions designed to benefit those who profited off the pain on West 69th Street and the decline of homeownership in America.

Analysts say Trump’s tax plan would make the mortgage interest tax deduction worthless to all but the richest Americans. The Trump administration also has reversed an Obama-era rule that made mortgages backed by the Federal Housing Administration more affordable to borrowers with good jobs.

“Most presidents have viewed homeownership as an accomplishment,” Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, told Reveal.

But Zandi said he can’t “discern that the Trump administration has any policy around homeownership one way or the other.”

Meanwhile, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, which oversees government-controlled mortgage company Fannie Mae, has launched a new initiative in which taxpayers backstop mortgage-backed securities on rental homes.

The first such deal, a $1 billion security agreed to in the waning days of the Obama administration, went to Invitation Homes, the company founded by Trump associate Stephen Schwarzman, which in August announced that it was merging with Barrack’s old company.

The End of Homeownership

Jessica Butler still can’t believe her family lost her grandmother’s home and the wealth that came with it.

“I loved that house,” she said. “I grew up in that house. I remember my grandma making ice cream in the back. Until the last year, we cooked together. When she passed away, I thought it would pass to my father. But that’s not what happened.”

Marcus Butler wishes his family could have kept their old home. “That’s what we were taught when we were younger,” he said. “You get a house, you pay for it, then you pass it on to the next child or grandchild, try to keep the house in the family.” (Photo: Stuart Palley for Reveal)

Marcus Butler wishes his family could have kept their old home. “That’s what we were taught when we were younger,” he said. “You get a house, you pay for it, then you pass it on to the next child or grandchild, try to keep the house in the family.” (Photo: Stuart Palley for Reveal)

For his part, Marcus Butler has never owned his own home.

After returning from the Army in 1974, he built a life in Los Angeles, working for 20 years loading luggage onto jets at Los Angeles International Airport. The pay was decent, but he never managed to save.

Marcus has declared bankruptcy three times to erase debt from high-interest credit cards. Today, he rents a small concrete-block apartment in the Baldwin Hills neighborhood with his wife, Sharon, an adult son and his baby granddaughter.

Last year, Sharon had a stroke, leaving her paralyzed from the neck down. She sleeps on a hospital bed in the living room.

Shown the pile of documents that trace the legal path of his childhood home, Marcus said: “I guess I can see how the game is played now, through the banks and through these companies. It’s a lot harder to get the American dream now, to own your own home.”

This story was produced by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization. Learn more at revealnews.org and subscribe to the Reveal podcast, produced with PRX, at revealnews.org/podcast.

<!— —> ![]()

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.