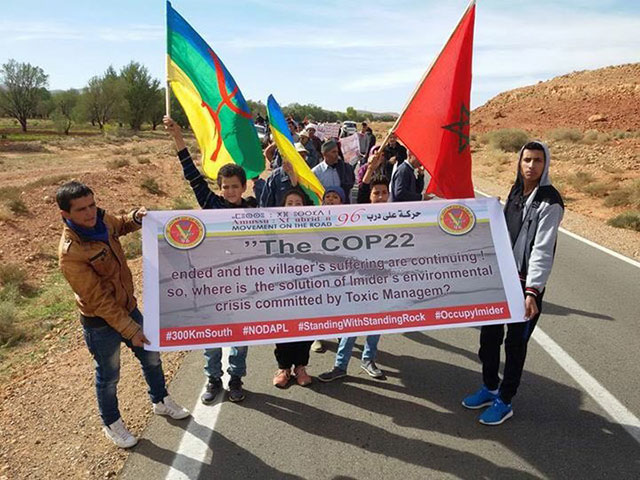

With a banner depicting their fight against the silver mining corporation Managem as a sister struggle to the fight against the Dakota Access pipeline in Standing Rock, Indigenous Amazigh people from the Moroccan town of Imider continued their protest against the mining corporation on November 20, 2016. (Photo: Moha Tawja)

With a banner depicting their fight against the silver mining corporation Managem as a sister struggle to the fight against the Dakota Access pipeline in Standing Rock, Indigenous Amazigh people from the Moroccan town of Imider continued their protest against the mining corporation on November 20, 2016. (Photo: Moha Tawja)

“In our language, we say ‘water is life’ or ‘water is soul,'” said Indigenous activist Moha Tawja. These words could be coming from the mouth of a #NoDAPL Water Protector at Standing Rock, but they’re not — Tawja is Amazigh from Imider, Morocco, a town 300 kilometers south of Marrakech.

The parallels between the Standing Rock Sioux and the Amazigh of Imider extend far beyond their respect for water. Thousands of miles apart, both communities struggle against extractive industries and a lack of respect for tribal sovereignty.

Imider is the home of Managem, the largest silver mine in Africa. Silver mining is a water-intensive industry.

“In 1986, Managem started taking water through an illegal well and arrested those who resisted,” Tawja said. “They still exploit these wells.”

Resistance against resource exploitation is also a central focus of the Water Protectors at Standing Rock. At present, the Standing Rock Sioux have been resisting the Dakota Access pipeline for eight months and experienced brutal repression from police on Sunday night. The 30-inch diameter pipeline is supposed to stretch 1,172 miles from North Dakota to Illinois and transport 470,000 barrels of crude oil a day. The emissions of this oil are equal to 101.4 million tons of carbon dioxide, or as much as 30 American coal power plants per year.

In a scene reminiscent of the policing that has occurred in Standing Rock, police in Morocco march in parallel to the Indigenous villagers from Imider to prevent them from reaching the Managem silver mine. (Photo: Linda Fouad)

In a scene reminiscent of the policing that has occurred in Standing Rock, police in Morocco march in parallel to the Indigenous villagers from Imider to prevent them from reaching the Managem silver mine. (Photo: Linda Fouad)

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe opposes the Dakota Access pipeline on grounds that it crosses sacred areas and ancestral burial grounds on the tribe’s unceded treaty lands. Furthermore, if the pipeline ruptures, it would pollute both their water supply and that of millions of others downstream on the Missouri River. This massive construction project violates the Standing Rock Sioux’s treaty rights, sovereignty and right to self-determination. The pipeline was given official approval without the tribe’s free, prior and informed consent.

An ocean and a continent away, the Managem silver mine usurps water from an Indigenous subsistence farming community that already suffers the impacts of climate change. Southern Morocco is on the frontlines of desertification, and droughts have been long in recent years.

Five years ago, fed up with the plummeting level of their wells, the Amazigh of Imider set up a protest camp on the top of a hill where Managem’s water pipeline runs. They turned off the pipeline and have occupied the hillside in nonviolent protest ever since. As in Standing Rock, what started as a short-term cluster of tents has turned into a semi-permanent community.

Lohou Okcha, whose family has occupied a protest camp in Imider for the last five years, told me: “The only difference between the struggles of Standing Rock and Imider is the type of corporation hurting them.” One is for silver, the other for oil and gas.

Nadir Bouhmouch, a Moroccan activist and filmmaker, added: “People are protesting because there can be no climate justice without social justice. The two are intrinsically linked.”

Indigenous protesters in Morocco have accused their government of using the COP22 climate talks to draw attention away from the environmental destruction that a silver mining corporation is wreaking 300 km south of the talks, in the town of Imider. (Photo: Moha Tawja)

Indigenous protesters in Morocco have accused their government of using the COP22 climate talks to draw attention away from the environmental destruction that a silver mining corporation is wreaking 300 km south of the talks, in the town of Imider. (Photo: Moha Tawja)

Indigenous Protests in Marrakech Surrounding COP22

On November 13, a group of Moroccans activists who call themselves REDACOP (an acronym for Reseau Democratique pour Accompagner la COP22 or Democratic Alternative to COP22) huddled together on a sidewalk in Marrakech, preparing to unveil a banner painted earlier that day. They blended in with a crowd of thousands of climate activists attending COP22, the annual UN talks on climate change.

From the buzzing chaos, echoes of chants floated forth: “People change, not climate change! System change, not climate change!” the groups shouted. “Justice climatique! Justice climatique!” A group of youth from The Green School in Bali carried a banner made of discarded plastic water bottles and frowning suns. The Indigenous bloc at the front of the march, a group composed of Indigenous leaders from as far afield as Canada and Ecuador, carried hand-printed banners designed by a Standing Rock artist that said: “Water is sacred. Water is life.”

As the march started to move, REDACOP activists stepped toward the front and unrolled their white canvas. “This march is helping the Moroccan regime greenwash its crimes,” it read in black, all-capital letters. In a country where activists are routinely imprisoned for speaking out against the king, this was a bold move.

REDACOP had held a press conference on the third floor of a building in Marrakech a few hours earlier. Its members see COP22 as a way of drawing attention away from lived experience of environmental and social injustice in their country — a way for the state to greenwash its environmental destruction.

REDACOP brought seven activists from Imider, to the state-sanctioned march in Marrakech to share stories of local resistance to environmental injustice. They used the hashtag #300kmsouth to publicize their struggle.

“COP22 is a way of drawing attention away from the real issues we live [with] here in Morocco,” Bouhmouch said. “It’s a way of hiding these issues.”

Resisting Managem

“The biggest silver mine in Africa has left us with pollution [and] unemployment, and has done nothing for our community,” Tawja said.

While a silver mine might seem to be a source of wealth for neighboring communities, all of the riches and jobs from the mine are going elsewhere.

“People tell us: You have the biggest silver mine in Africa, and you’re coming here for work?” Tawja said. Instead of hiring locals from Imider, Managem is “bringing [in] people from the outside who don’t care about the land and don’t care about the pollution that the mine creates.” As a result, men have to migrate to the cities in search of work. Women in rural Morocco are left behind to deal with the impacts of climate change.

“If you’re driving your own car, you’ll be more careful,” Bouhmouch added, explaining the reason for bringing in outside workers. “If you’re driving a rental, you won’t care how you shift the gears.”

Water pollution is at the core of Amazigh community concerns in Imider.

“Women are reporting higher rates of miscarriages, and there are many cases where the woman or child dies in birth,” Okcha said. “Migratory birds are falling out of the sky after they drink from the toxic waste pools surrounding the mine.”

Many locals suspect that water contamination and toxicity from the Managem mine is to blame for the decline in human and nonhuman health in the surrounding areas, but there’s no way to prove it. Not a single study has been done to learn the impact of this mine on the community.

“Imider is a small example of how this regime treats all Moroccans,” Bouhmouch said. “This regime gives all priorities to corporations.”

Bouhmouch is not optimistic that the Moroccan regime will take action to protect the people of Imider at the expense of the mine.

“Decisions will not come from the top. Local work on the ground is the only solution,” he said. “Climate change is very political. You can’t depoliticize it. This Moroccan regime encourages companies like Managem to pollute and exploit.”

As Amazigh activists continue to push for an end to pollution and corporate encroachment, they point to parallel efforts in Standing Rock as a mark of the global nature of Indigenous resistance.

Okcha expressed gratitude to members of Indigenous communities abroad, including those at Standing Rock.

“I want to thank Indigenous people internationally who have come to support us. We are fighting the same struggle,” Okcha said. “Let’s continue to work locally, while reaching out our hands internationally. We are fighting the same struggle.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $22,000 by the end of today. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.