Erick walks slowly toward a gas station on the corner of a busy intersection on the Lower West Side of Chicago. He grabs a stock of paper towels that hang from a dispenser below the windshield wipers near the gas pumps.

He walks unsteadily: Every time he takes a step, he winces while placing his hands on his stomach. I ask him if he is OK, but he shakes his head “no.” As he tells me his health condition is deteriorating, he lifts his shirt to show me the scars associated with what he thinks is a bacterial infection.

Erick knows who I am. I often see him panhandling at another nearby corner. I interviewed him soon after I released an investigation last April that aired on WBEZ Chicago Public Radio and NPR’s “This American Life,” exposing a practice in which drug users from Puerto Rico were sent by Puerto Rican authorities to unregulated rehab centers in Chicago and other cities across the United States.

Under a program called De Vuelta a la Vida run by the Puerto Rican state police and other programs run by municipal agencies in Puerto Rico, hundreds of Puerto Ricans have come to Chicago expecting to enter comprehensive, high-quality rehab centers with excellent doctors, nurses and even swimming pools. Instead they end up in unregulated, crowded homes. The places are known as “24-hour groups” – rehab homes where people struggling with addiction find themselves sharing overcrowded rooms, sleeping on dirty mattresses or on the floor, and facing routine humiliation as part of a protocol supposedly intended to keep them on the path to sobriety.

People taken to these homes are required to stay there for up to 90 days and are subjected to a “tough love” approach that includes intense group therapy sessions, verbal abuse and insults from peers and “padrinos” (godparents) – the leaders of the groups. Feeling deceived by the false promises, many like Erick have left these “rehabs” to venture out on the streets of an unfamiliar city.

The night I saw Erick, the temperatures were dropping and a windy rainstorm was on its way. I asked whether he would rather be back in one of those rehab centers instead of being in the cold. But he quickly said no.

“The way they treat you there might help others, but it doesn’t help me,” he said slowly heading back to the corner where he had been panhandling all day.

Many former drug users defend the 24-hour rehab groups, arguing that the hardcore therapy, name-calling and long group sessions serve as eye-openers that in turn help them realize the damage they have caused themselves and their love ones.

But for others like Erick, the tough treatment is too much to bear, especially since many of them already have been victims of abuse, have mental health issues and have experienced trauma caused by their own addictions. And there is no denying the broken promises: People are being led to the United States for sorely needed comprehensive treatment – and presented with neglect and abuse.

Connecting Drug Users to Adequate Services

Melissa Hernandez volunteers her time during the week to deliver infection control supplies, food and clothes to drug users who came all the way from Puerto Rico looking for drug rehab treatment and are now living on the streets of Chicago. (Photo: Bill Healy)

Melissa Hernandez volunteers her time during the week to deliver infection control supplies, food and clothes to drug users who came all the way from Puerto Rico looking for drug rehab treatment and are now living on the streets of Chicago. (Photo: Bill Healy)

The stories of the Puerto Rican drug users who are still wandering the streets of predominantly Latino neighborhoods across Chicago have angered elected officials, service providers and even residents who want to establish a network of services to help this new population.

One of them is Melissa Hernandez, a mother of two, dental assistant and former IV drug user who said she has been outraged ever since she first heard the story.

Since May, Hernandez has been walking through Chicago neighborhoods such as Back of the Yards, Little Village and Humboldt Park, looking for drug users that were sent from Puerto Rico to the 24-hour rehab homes, aiming to assist them in finding real support.

Drug users from Puerto Rico come to Chicago thinking they will get quality care, but instead end up in rehab homes with no medical professionals in sight.

I met her at a Dunkin Donuts a few months later near Humboldt Park, a largely Puerto Rican neighborhood on the city’s west side. She was on the phone talking about a person who needed drug addiction services. She had a heavy pile of papers tucked inside a folder crammed with notes, telephone numbers written all over the cover. She was speaking firmly, making sure the person on the other line would respond to her request to find immediate drug rehab services for the drug user she was trying to help.

Hernandez’s family is from Puerto Rico, too. Although she grew up in Chicago, her Spanish has a slight Puerto Rican accent. Her warm personality makes her well-suited for the job she has set out to do: She is working to kick-start a program called the Puerto Rico Project, geared toward supporting drug users who’ve been sent from Puerto Rico to unregulated drug rehab homes – many of whom are now homeless.

On Monday and Friday nights, she visits the places where she knows she will find her clients and delivers food, infection control materials and clothes. During the day, while her kids are in school and before her work shift begins, her outreach continues. Once she finds the men and women she is looking for, she completes an intake form, gets their full stories and connects them to services. She begins by asking how they came to hear about the program, while in Puerto Rico.

“I ask them, who they talked to … who picked them up, how long did they wait, what group they went to, what was their experience in the group, what happened to them,” she said.

So far she has identified about 100 men and women from Puerto Rico who are wandering the streets of Chicago while battling an addiction. But even as she tries to build a network of services for drug users, securing full access to those services has been challenging, Hernandez said.

Some of the men and women she serves, she said, are stuck in the cycle of their addiction – and even when she shows up willing to take action and connect them to services, it’s not always that easy.

“Some guys have even said to me, ‘Melissa, I am gonna be really honest with you, I am really, really sick. I am gonna try to get some money, I am gonna panhandle and once I am feeling better, I’ll call you,'” she said.

Being a former drug user herself, Hernandez understands how hard it is to break the cycle of addiction and endure the physical and emotional symptoms associated with quitting. She understands that people often waver over whether they want to commit to recovery. “I guess a major challenge is just going back and forth and staying on top of it, telling them that there is help and professional services,” Hernandez said.

Some people Hernandez meets have clearly been traumatized by their experiences at the 24-hour rehab groups. She showed me pictures of two men, one who had his eyebrows shaved and another one who had his head shaved. Both incidents happened as a form of punishment for relapsing in two different 24-hour rehab groups, Hernandez said.

And there are other sad stories.

“We actually had one young kid who ended up in the UIC [University of Illinois at Chicago] psych ward,” she said. “He was here since August and he was led to one of these groups. He ended up leaving – they took his government documents and I guess when he ended up leaving, he couldn’t find a job, he couldn’t get an ID, he had nothing. He tried to kill himself, didn’t know what to do. It’s sad but it’s a story I hear all the time.”

The many stories that Hernandez and I have heard are all too similar. Drug users from Puerto Rico come to Chicago thinking they will get quality care but instead end up in rehab homes with no medical professionals in sight. Many times their IDs and important documents are stolen or lost there, and once they walk out of the groups they find themselves in the streets, alone, many times in the middle of winter, without identification or prospects for work or housing, and with a strong addiction to feed.

Take Manuel, a man I got to know during my initial investigation. When I met him he was panhandling in the corner of a predominantly immigrant neighborhood just two weeks after he arrived.

The 24-hour rehab home he was sent to is called Segunda Vida (Second Life), and it’s a dilapidated gray brick building on the South Side of Chicago. Manuel, like the other residents, had to sit through long hours of group therapy, endure insults and stomach the so-called “tough love” approach. However, after three days, he’d had enough: He walked out, alone and without his documents. Manuel was finally able to get his birth certificate, Puerto Rican ID and medical records back after I accompanied him to Segunda Vida with an audio recorder in hand and refused to leave without the papers.

Manuel was sent to Chicago by the Puerto Rican police. He was suffering from a severe health condition, and he needed medicine and constant medical attention. Manuel also has serious mental health problems that have been getting worse since he arrived in Chicago.

He has been arrested multiple times and complains that he is often harassed by local police who know about his addiction and don’t want to see him panhandling in high-trafficked streets. Other Puerto Rican drug users in the area have similar complaints about the police.

“I have been hospitalized six times due to my health issues, I have been in the psychiatric hospital three times, I have been dealing with depression,” Manuel said. When he is not in jail, he lives in an empty house with six other Puerto Ricans who came to similar rehab groups and are now on the streets.

“And believe me, I am afraid of the winter,” he said. “There comes that white monster again.”

Last time I saw Manuel, he had been rushed from a halfway house where he was under house arrest with an electronic ankle monitor to an emergency room due to complications with his liver. He also spent several days under psychiatric care because he threatened to kill himself multiple times.

“When I am done here, I don’t want to go back to the streets, I don’t want to experience what I went through last year,” he told me.

Looking to Puerto Rico for Answers

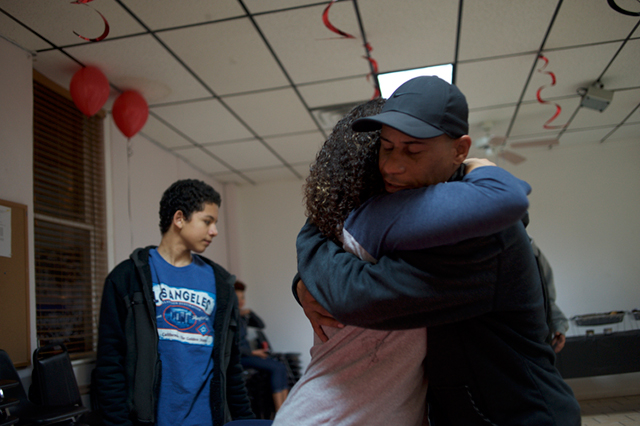

Melissa Hernandez is kick-starting a campaign (or organization) to help Puerto Ricans who came to Chicago looking for drug rehabilitation treatment, but instead found themselves in unregulated 24-hour groups run by former addicts. (Photo: Bill Healy)

Melissa Hernandez is kick-starting a campaign (or organization) to help Puerto Ricans who came to Chicago looking for drug rehabilitation treatment, but instead found themselves in unregulated 24-hour groups run by former addicts. (Photo: Bill Healy)

Hernandez has been working closely with Illinois State Sen. William Delgado (D-2), one of the elected officials who has vowed to investigate the unregulated rehab homes and work with authorities in Puerto Rico to establish an adequate referral system for those seeking rehab services in the future.

With Delgado’s support, Hernandez has connected with other service providers and participated in meetings and strategy sessions to figure out how to serve the people who have been funneled into these group homes by government officials, service agencies or family members.

Hernandez said she is collaborating with at least six licensed rehab agencies in Chicago, including Rincon Family Services, Haymarket, Lake Shore Hospital, New Vision and Health Care Alternative Systems. Those agencies are working with her to identify and assist drug users from Puerto Rico in need of help.

“We have been fortunate to save many of these folks with our own services, despite our own deficit,” Delgado said.

Aside from connecting drug users to services, Delgado said he’s been trying to communicate with Puerto Rican government officials, but so far it has not been an easy task. One of his main goals has been reaching out to the municipalities that he knows were involved in sending people struggling with addiction off the island. One city that has particularly caught his attention is Bayamon and its program called Nuevo Amanecer.

Delgado said the mayor of Bayamon, Ramón Luis Rivera Cruz, and the director of Nuevo Amanecer, Gladys Cintron, have ignored his many requests to discuss the impact of sending drug users to unregulated rehab homes in Chicago.

Many of the people who were sent to Chicago say Cintron connected them to the rehab homes; sometimes, the municipality of Bayamon pays for a one-way plane ticket to Chicago.

I have made several attempts to speak with Cintron and the municipality of Bayamon about the referral strategies that are being implemented by Nuevo Amanecer. On April 24, after repeated requests, I received an email from the municipality of Bayamon stating, “The program Nuevo Amanecer only uses homes that have been certified and legally established in Puerto Rico and in the United States.”

The statement said that once the patients are placed in a program, they are monitored either through social networks, via telephone and or visits to the center.

But some of the drug users that Hernandez or I have interviewed say Gladys Cintron sent them to the unregulated 24-hour rehab homes. Erick is one of them.

Hernandez said she met with Cintron during her short visit to Chicago last October. Cintron wanted to find the drug users whom she had referred under Nuevo Amanecer and are now on the streets. She wanted to offer them a ticket back to Puerto Rico, Hernandez said.

According to Cintron’s Facebook page, she visited several 24-hour groups. She posted a note on Facebook saying that she toured several streets in Chicago looking for her “children,” as she calls the drug users in the program. In her post, Cintron wrote that she was happy to learn that none of her “children” were living on the streets, and posted pictures of her with other men outside of some 24-hour group homes.

I called her to ask about the visit, but she declined to comment, adding that she had already met with Hernandez to discuss her motives.

According to the April statement from Bayamon, the municipality has sent 40 people to Chicago. In the last decade, the Puerto Rican police De Vuelta a la Vida program said it has transported 758 people to the mainland of the US for treatment. Of those, 120 were sent to Chicago. From 2007 to 2013 the municipality of Juncos said it sent 259 drug users to other cities in the US, and 56 of them were referred to Chicago. The municipality of Caguas said it has only referred 25 people in the last three years.

But service providers are skeptical about those numbers. In some parts of Puerto Rico, the practice of sending drug users off the island for treatment has been in place for years, and so far there has been no comprehensive review of those practices by any state agency or municipal organization.

Senator Delgado said he has been in communication with the agency that oversees drug addiction programs in Puerto Rico, which is known as ASSMCA (Administración de Servicios de Salud Mental y Contra la Adicción), but no concrete action has yet been taken. He also said he has been in contact with Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart to further investigate what is happening on the Chicago side of the equation.

“I am working with County Sheriff Tom Dart to review and to recommend any legal course of action that needs to be taken here in Chicago to assure people are not trapped in uncertified, unsafe conditions and that they have a chance to get real services to live a successful and decent life,” Delgado said, adding that he is concerned about possible elements of human trafficking, welfare fraud and ID theft happening as part of the 24-hour group system.

Abdon Pallasch, the director of public affairs for the Cook County Jail, didn’t provide any specific details about the investigation, but said his agency is trying to identify drug users from Puerto Rico who wound up in jail for retail theft and other related small violations in hopes to fast-track them out of jail and into rehab under a new “rocket docket” law.

But there are some challenges when trying to identify and connect these drug users to rehabilitation services, Pallasch said. “Most of the guys aren’t there long enough for us to get up and run a tally of the people who have come through the jail and have been part of the deceptive unlicensed clinic scheme, but the infrastructure is there for these guys to get the help they need if they are willing to stick with the program.”

Pallasch said the jail has identified eight individuals sent from Puerto Rico to Chicago group homes who have been in and out of the Cook County Jail system, costing the jail and taxpayers about $88,000 in a period of two years.

Last May, Dart asked the federal government to investigate the issue of the group homes, and filed a fraud report with the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) warning that the agency could have possibly been funding De Vuelta a la Vida and Nuevo Amanecer.

The 24-Hour Group Homes Persist

Unregulated 24-hour group homes have existed in Chicago for decades, subjecting drug users to long hours of required group therapy and, in many cases, to insults, humiliation and mockery. Some of those groups are newer than others and some are part of larger networks – like the International Movement of 24-hours, with locations in Chicago and other cities in the US and also in other countries including Mexico, Colombia, and even Spain.

Other groups spring up now and then. In many cases former drug users come together to start their own rehab homes and provide a space where people struggling with addiction can eat, sleep and receive long hours of group therapy for several months. They make their own rules, borrow concepts from Alcoholic Anonymous and many times bring the tactics they’ve learned in other 24-hour rehab homes.

The members in many of these groups take pride in their sobriety and the fact that they have helped other addicts with their addictions without the assistance and guidelines of any government agency. They survive on donations and contributions made by current and former members. Individuals who have lived and received group therapy in these group homes also said that in some cases eligible participants are taken to the Illinois Department of Human Services (IDHS) offices to apply for a LINK (food stamps) card. The card is then used to buy food for the entire group.

The persistence of these groups demonstrates the existence of a huge, largely unmet need in Chicago: accessible around-the-clock services where drug users can find shelter, food and a community of peers.

Segunda Vida, the group where Manuel and many other drug users have been referred to by the Puerto Rican authorities, was founded by former members of a group called Vida, a 24-hour rehab home located across the street from an elementary school on the South Side of Chicago.

In 2006, a man fatally stabbed another man with a kitchen knife at Vida during a group-counseling meeting that was going late into the night, according to a Chicago Tribune article and police records.

The same news article said the perpetrator later admitted in a videotaped confession that the man he stabbed was “being overly hard on him” during the group therapy session. Shortly after that, Vida closed its doors. In addition to the stabbing incident, nearby neighbors and school officials complained to local authorities that students were being harassed by the men who lived in the building and often hung out on the corner smoking cigarettes.

After Vida closed, some members continued on with Segunda Vida and others moved on to start their own groups or simply joined existing ones.

Some of the Puerto Rican drug users whom I have talked to know each other well in and outside of the 24-hour groups. Many have attended the same groups in the South Side and have sat through long hours of testimony and group counseling together. They know each other’s lives, their struggles, their addictions and how far they are willing to go to get drugs.

The padrinos (godparents) know the lives of many drug users as well. They have been sober longer than the people they work with. They don’t have formal training, and their knowledge of how to deal with addiction comes from the streets. While some group participants develop strong and long-lasting relationships with the padrinos, others complain about the padrinos berating, insulting and yelling at them.

The persistence of these groups demonstrates the existence of a huge, largely unmet need in Chicago: accessible around-the-clock services where drug users can find shelter, food and a community of peers. The number of people seeking treatment – or simply seeking a place to live, as a drug user far outweighs the available resources, and people are desperate.

The “tough love” approach and the long hours of group sessions used at the 24-hour groups have helped some drug users stay sober. They even hold annual events where they celebrate each other’s sobriety. But others do a few months of group therapy, leave and relapse again.

Recently, at a group called Blanco y Negro (Black and White) on the South Side, a man stood in front of a small crowd to share his testimony. He was wearing jeans and a bright green shirt. He was tall and handsome and had a strong Puerto Rican accent. He talked about how he lost the past 10 years of his life struggling with his heroin addiction. His testimony was full of guilt and disappointment.

“I got curious and I finally tried heroin, and I ended up marrying her,” he said, also discussing his experiences with homelessness and the pain he caused to his family.

He said he regretted the times when he walked away from the 24-hour group, adding that regardless of the rough treatment he experiences there, Blanco y Negro is still the one place he can call home until he finally gets back on his feet.

“I was doing good for a while, when I was in the group, but when I left the group whatever I acquired I tossed it in the garbage,” he said, adding that God keeps telling him to stay in the group, because that’s where he can truly get the spiritual strength that he needs to keep fighting his addiction.

My recent investigation focused on two 24-hour rehab groups where many Puerto Ricans were being sent – Segunda Vida and El Grito Desesperado (The Desperate Scream). After being in the spotlight for a few months, Segunda Vida took its small logo down from the grimy second-floor window where it had been displayed. But the group is still up and running. Leaders have denied any mistreatment, ID theft or use of members’ LINK cards. Its members said they are just a support group, providing a place where addicts can live and receive group counseling. They also said hundreds of drug users have found sobriety thanks to the group.

El Grito Desesperado closed down one of its sites and is now operating in one location along Cermak Road in Chicago. That rehab group also took down its signs.

The Illinois Department of Human Services’ Division of Alcohol and Substance Abuse said it has inspected several sites. The agency has categorized these 24-hour groups as AA support groups, saying they “are not subject to the oversight and regulations that rehabilitation and treatment facilities are. If there is a criminal allegation, that is subject to the jurisdiction of law enforcement authorities, or in the case of building code or zoning violations, subject to the jurisdiction of the City of Chicago.” The statement went on to say that, “a license is required through [the division] in order to operate an addiction treatment facility.”

In the past, several city departments have said they don’t have any jurisdiction over this matter either.

In the meantime, some 24-hour rehab groups like Blanco y Negro still advertise themselves as rehabilitation centers that offer psychotherapy and treatment to Spanish-speaking people for neurosis, traumas, bipolar disorders and depression, along with addiction. And although these centers continue to use rough tactics and remain largely unregulated, they are fulfilling a shortage of treatment options available for people struggling with drug addictions. Even though drug users know they may be subject to verbal abuse and humiliation at these centers, some continue to seek them out because the doors of these rehab homes remain open at a time when many more formalized centers are inaccessible.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.