Part of the Series

Solutions

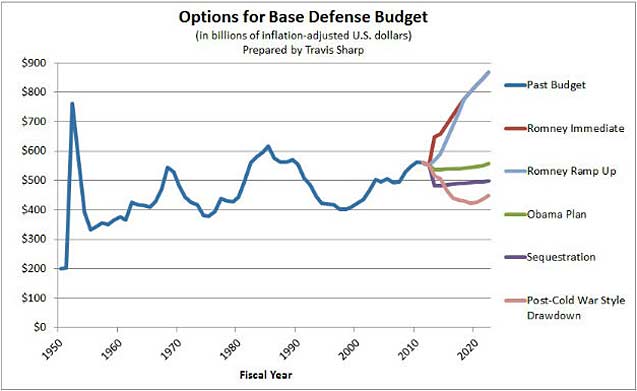

In August 2012, I wrote a Solutions column about a disturbing chart that showed defense spending was marching endlessly upward, even though we were winding down two of our longest wars. I didn’t think anything would top that chart, but look at this chart above, which was shown on the Rachel Maddow show on October 8 and taken from Foreign Policy’s blog. I was shocked, even after investigating the Pentagon budget, in particular, weapons procurement, for over 30 years.

The chart shows President Obama’s disconcerting defense budget isn’t going down after the wars; it shows the potential cuts that Congress put itself under with the sequestration rules if they don’t agree on a budget deal (which has caused howls of pending disaster from Republicans and some Democrats); and it shows the post-cold-war-style drawdown, where, historically the defense budget should draw down after ending wars. Even though we have heard that Mitt Romney has taken up with the Bush-era neocons and planned to raise the defense budget $2 trillion above the Pentagon’s requested budget over the next nine years, this graph gives a gut-punching visual of the almost straight-up trajectory of the defense budget under a Romney presidency. I lived through Reagan’s huge defense budget buildup, but look at it, starting in 1980 on this chart of constant dollars, and you can see that Reagan’s efforts were puny compared to what Romney wants to do.

Even though Romney claims that we need this massive increase – which will take us to Korean War levels with no planned war – he has not laid out in any detail what he plans to accomplish with this money. He talks about building more ships and three submarines a year and increasing the buy on the F-35 fighter planes, but he fails to put it into a picture of how submarines and technically troubled planes are going to make us safer from the insurgency wars that we might face in the future. In the “Mad Men” view of the world, these cold-war-style weapons are suppose to make us safe, but the United States faces a different world and a different threat than it did in that era. And never mind that we already spend more money on our defense than the rest of the world combined.

I saw some of those cold war relics when I went to Fleet Week in San Francisco this weekend. It is ironic that, although Fleet Week is still held every year, San Francisco no longer has any military bases nearby, and the city is decidedly anti-war and anti-Pentagon. The sailors who were roaming the streets were warmly welcomed by the city and there were families, mainly sons and fathers, lined up at Coit Tower with me to get a good look at the loud and impressive flying of the Navy’s Blue Angels in the F-18 aircraft.

But before they got started, there was an airshow of many of the weapons that we claim make us strong as a nation but were designed for a long-gone cold war. The B-2 bomber with its black, bat-like appearance lazily flew circles around the waterfront before departing the area and home to its only Air Force base in Missouri. This bomber was to be the premiere bomber of the cold war, with its black stealth skin and unique design. It certainly looked exotic flying against the bright blue California sky.

I remember the Congressional fights over this plane because of its technical problems and its preposterous maintenance, which pushed the price of a single plane to around $1 billion, or $2 billion if you count all the associated program costs. The unsuccessful effort to cancel the plane was bipartisan, with Ohio Republican representative John Kasich joining up with liberal California Democratic representative Ron Dellums, an effort that you will unlikely see in the now politically overheated Congress.

The much-vaunted stealth coating on this plane can be defeated by long-wave radar, and it also ensures the planes’ maintenance requirements are ridiculously expensive. Each of the 20 planes has to have its own air-conditioned hangar to protect the stealth coating from rain and heat. The maintenance costs $3.4 million a month for each plane, double the maintenance cost of the aging B-52 bombers that are still in use and were first made before I was born. Yet we have only used the B-2 in limited ways in the Kosovo war, a little in Iraq and Afghanistan and a little in the Libyan civil war. The B-52 bomber that had its first mission in 1955 is still in use, with 94 of the original 744 planes currently operational, and the Air Force would like to keep some of these bombers flying until 2040.

Another plane on exhibit in the air show was the now-cancelled F-22 Raptor fighter. With its large size and large triangle wing, it looked like a typical cold war weapon, except for its stealth design. It zoomed around the San Francisco Bay, often flying straight up and then spiraling down to the water before pulling itself up. It was loud, flashy and spectacular, and the crowd clapped and cheered when it flew low by us with a deafening sound. But what the crowd did not know is that this plane started out as the Advanced Tactical Fighter in 1981 and was suppose to be the replacement for the F-15 fighter and the venerable F-16 fighter. Instead, it cost the US $66.7 billion to build 187 planes before the Raptor was cancelled. It has not seen combat, and its deployment has been very rough, including problems with the electronics and with the oxygen system, which made pilots sick. One pilot died while having problems with the oxygen but the Air Force claimed it was pilot error.

The Air Force has had to ground the plane repeatedly for the oxygen problem, and it got egg on its face when two pilots risked their careers to go on the television show “60 Minutes” to say that many of the pilots did not want to fly the plane because it was not safe. In isolation, in this airshow, the plane did look flashy, but I wonder how the crowd would feel if the show had a program that showed how much taxpayers paid for it and listed the technical problems for a plane that has not seen combat and has problems even being deployed. The Air Force cut many of its planes from the airshow circuit this year because of costs but left in the F-22 because, what else is it going to do?

I knew that this airshow’s goal was to push and sell its gee-whiz planes to the public, and based on the whoops and hollers of the crowd, even in this peace-oriented city, the spectacle had the desired effect. The aerospace organization NYCAviation outlined the Air Force’s goal with these airshows, and the concerns about cutting out more of the planes:

It is not just the airshow circuit that will lose out as a result of the cuts, though. Indeed, the Air Force itself stands to come out on the losing end of the deal. With less presence in the public eye, the branch will lose a substantial channel by which to connect to the nation it serves.

Considered a powerful tool for recruitment, “[the single ship demo teams] make you feel directly connected to those who are fighting tooth and nail for our interests abroad. They create a fire in your gut, a powerful sense of exhilaration and patriotic defiance,” says defense blogger Ty Rogoway, owner of AviationIntel.com.

Since many of these planes, ships and tanks have proven to be more expensive than, and inferior to, the ones they replaced, the military must glorify these weapons and show them off to the public – but also, most importantly, it must hold regular dog and pony shows for the members of Congress who fund them. As someone who has been on these Congressional junkets, including one to drive and fire the M-1 tank, I can see that impressions win over test results and audits, and these weapons’ mystic status must be protected, as anyone who has ever watched the Military Channel can see.

So, how is it that, although we are paying more for each generation of weapons, we are getting fewer of them, and they still have a myriad of problems? Two contributors in a book called Pentagon Labyrinth outline the system that allows this madness to continue.

Winslow Wheeler, who worked for the Congress for many years overseeing defense, describes how the system works:

Understatement of cost does not occur in isolation in the Pentagon; it is accompanied by an overstatement of the performance the program will bring, and the schedule articulated will be unrealistically optimistic. Once the hook is set in the form of an approved program in the Pentagon (based on optimistic numbers) and an annual funding stream for it from Congress (based on local jobs and campaign contributions), the reality of actual cost, schedule and performance will come too late to generate anything but a few pesky newspaper articles.

…

Also, the new systems rarely, if ever, bring a performance improvement commensurate with the cost increase. In some cases the new system is even a step backwards. The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is a good example. Among the aircraft it is to replace is the 1970s vintage – but still much used and almost universally praised – A-10 close air support aircraft. Even if the F-35 stays at its 2010 purchase price of over $150 million per aircraft (which it will not), it will cost ten times more than an A-10. For that additional expense, it will have less payload than an A-10; it will not be able to loiter over the battlefield to help troops engaged in combat hour after hour; it will be too fast to be able to find targets independently, and it will be too fragile and sluggish to survive at the low altitude it must operate at to be effective, even against the primitive small arms and machine gun defenses terrorists and insurgents can mount. To make matters worse, the F-35 will lack the extraordinarily effective 30 mm cannon the A-10 carries.

Andrew Cockburn, a journalist who has been following the follies of the Pentagon for decades, tells us to follow the money to understand the problem:

… as observed long ago by Ernie Fitzgerald, who battled this culture as an air force official, the contractors are “selling costs,” not weapons systems. To the extent that they can improve their “products” by making them more complex and thus more expensive, they prosper. The inevitable corollary has been that the number of items produced for any one program goes down as the costs zoom up. Hence the F-35 fighter, currently under development for the Air Force, Navy and Marines as well as a number of foreign air forces, was originally slated for a production run of 2866 planes at a unit cost per plane of $81 million. Already, well before the plane has completed testing, the unit cost has soared – thus far – to $155 million each, and the total buy has accordingly shrunk to 2457. Further production cuts, as foreign buyers drop out, are inevitable, which will in turn boost the unit cost of the remaining planes on order, leading to further cuts, and so on.

Once this disconnect between the official (weapons systems of postulated quality and quantity) and actual products (costs) marketed by the defense industry is clearly grasped, other distressing aspects of the U.S. defense system become easier to understand. Escalation of costs required inefficient management practices, employing twenty people to do, supervise, manage, and administer the work of five, for example. “Inefficiency is national policy,” declared the Air Force general managing the vastly over-budget F-111 bomber program in 1967. But inefficient production tended to produce inefficient performance. The great missile gap fraud of the early 1960s led not only to the abandonment of all cost restraints on the crash programs instituted by the Kennedy Administration to “catch up” with the Russians, but also some egregious technical failures. The guidance system for the Minuteman II ICBM, for example, was so unreliable that 40 percent of the missiles in the silos were out of action at any one time. Replacements had to be bought from the original contractor, who thereby made an extra profit thanks to having supplied faulty sets in the first place.

As they point out, this problem has been going on for years, but is getting worse as more money is shoved into the Pentagon with no change in this dysfunctional system. We also need to price weapons by how much it costs to build that particular weapon and not price them by historical costs – that is, based on the last failed plane with all the fraud, waste and fat incorporated into the base price of the new plane.

If we get the Obama military budget, there will still be big problems and waste unless there is substantial change in how the Pentagon buys its weapons. If we get the Romney military budget, with $2 trillion more to just throw around, the weapons will get more expensive, more prone to problems, and we will buy fewer and fewer of them. With a Romney administration pushing that much more money into this deeply flawed system, we may lose any chance of changing it, cutting the budget and using the money more wisely for another generation. The Pentagon bureaucracy and its contractors will be like kids in a candy store, buying weapons that have little connection to any threat we face. We will be throwing money fuel on an already out-of-control fire. Defense spending will continue and escalate as a test of how strong we can make ourselves look to the rest of the world with air shows and flashy demonstrations that have no real connection to weapons effectiveness in the battlefield.

I am wondering: If the F-35 fighter gets into more technical and financial trouble in the next few years, will I see it screeching around the San Francisco Bay in a future Fleet Week? You can count on it – and the United States will be weakened even more with its unchecked military spending while other vital needs in the country go wanting.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.