“We would need three years to tell the story, being optimistic,” says Mirta Colón Pellecier, sitting in the doorway of her Section 8 apartment on a hot afternoon in March. A light breeze flows through the open door and is caught by a fan, blowing the fresh air into the living room. A framed photograph of Colón and her six adult children stands on a table to her right. To her left, Colón’s youngest son sits in the kitchen with his girlfriend, preparing to leave for work at his second job. “He was nine years old when I moved to Gladiolas. My daughter was 13”.

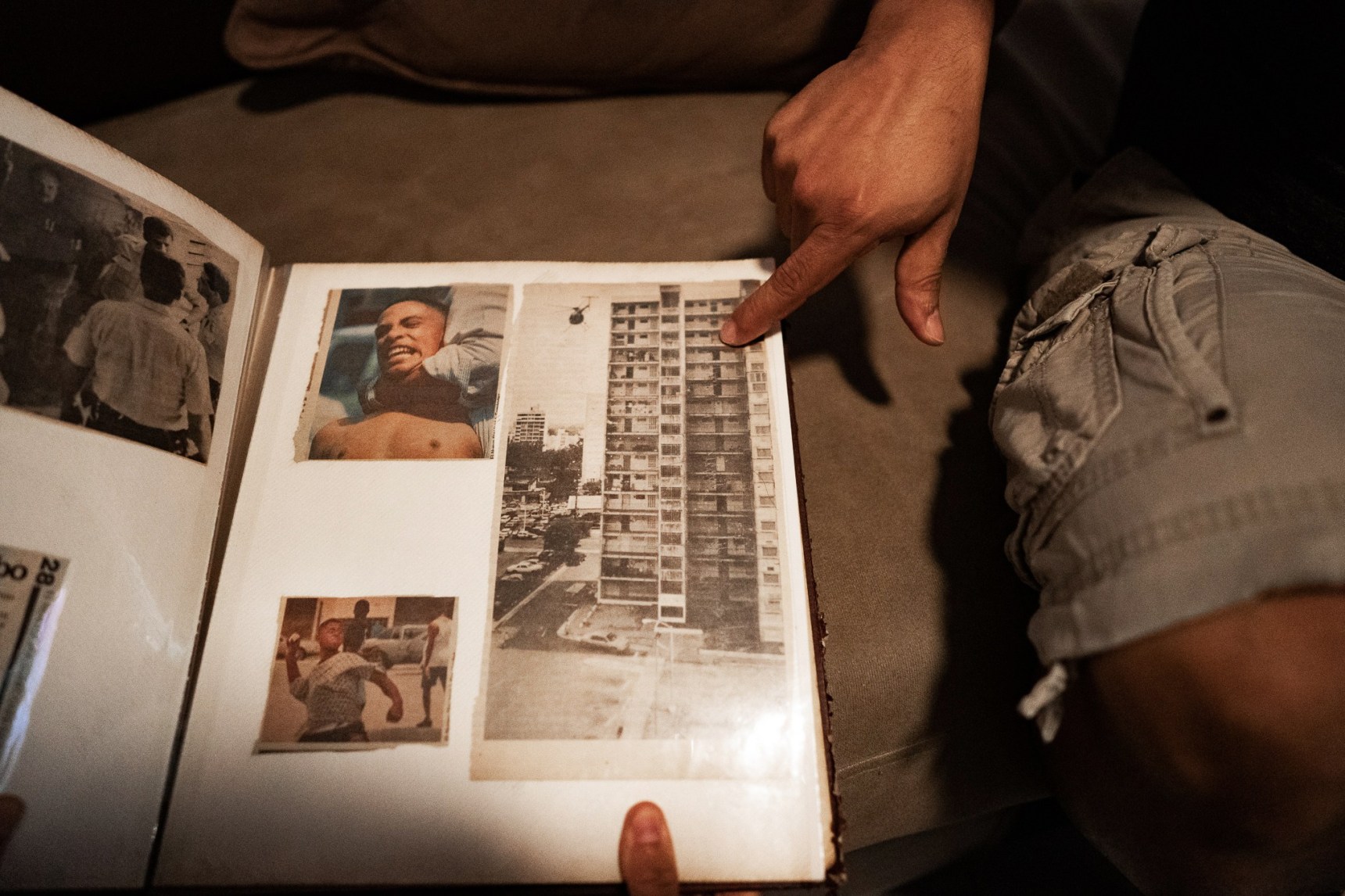

In 2006, Puerto Rico’s Department of Public Housing (Administración de Vivienda Pública, AVP) was authorized to evict 412 families from Las Gladiolas, a 37-year-old public housing complex on Quisqueya Street in San Juan. The residence sat just past the Milla de Oro (“The Golden Mile”), an affluent stretch of Hato Rey and a center of commerce where Puerto Rico’s major banks are headquartered. The four-tower residence, built in 1969, was home to 676 units left partially vacant by residents forced out as a result of apartments in disrepair, police raids, and numerous other strategies used by authorities to vacate the residences beginning in the early 2000s. The AVP and the private-sector company paid to manage Las Gladiolas left apartments dilapidated, elevators broken, and buildings often without access to water or electricity. The towers were a well-known “servi-carro” through which wealthy locals could stop for convenient access to illicit drugs. Public officials used this reputation to criminalize the community and advocate for the demolition of the buildings against the wishes of residents, many of whom called the towers home across generations.

“We realized that there were other intentions than to maintain the community. Officially, nothing was said. But we knew,” says Colón, 63, who moved to Las Gladiolas in 2001 and has spent the past 18 years organizing on behalf of her community. She recalls a campaign of neglect and harassment by public officials, private management, and the insular police force so extreme that life at Las Gladiolas was no longer bearable. Organized residents who demanded better living conditions spent nearly a decade resisting eviction orders. Ultimately, the department branded the elimination of a vital public service as an initiative to revive the community and surrounding neighborhoods, successfully resulting in the demolition of the towers in July 2011. Eight years later, residents’ concerns that the evictions would result in the permanent displacement of community members have proven valid. As of September, only 14 former residents have managed to relocate to a privately-operated, mixed-income housing complex constructed at the same site called “Renaissance Square.”

***

Las Gladiolas earned its reputation as a hub of crime in part through an operation launched in 1993 by then-governor Pedro Rosséllo González called Mano Dura Contra el Crimen (Iron Fist Against Crime). The program, an extension of the United States’ War on Drugs, fostered dozens of raids on Puerto Rico’s public housing residences with the assistance of the National Guard. The concentrated, militarized security presence in low-income communities served as an initial “shock,” allowing for the implementation of neoliberal policies aimed at sabotaging safety net programs like public housing. The initiative’s success solidified a privatization effort begun in 1992 by then-governor Rafael Hernández Colón, which Puerto Rico’s politicians branded as an effort to rid the island of its “culture of dependency.”

One of these policies included AVP’s decision to distribute the management of each development among 11 private, for-profit companies. Residents say that the policy, which is still in place, is primarily responsible for deteriorating conditions in existing apartments. In Puerto Rico, over 43% of the island’s residents live below the poverty line, and the income per capita was listed as $12,081 annually as recently as 2017. Rosséllo’s anti-crime initiative successfully vilified some 53,000 residents of Puerto Rico’s Public Housing Authority (the second-largest in the United States after that of New York City). The AVP has since expanded this effort through the forced removal of residents, the demolition of existing public housing, and the construction of privately operated, mixed-income residences in its place.

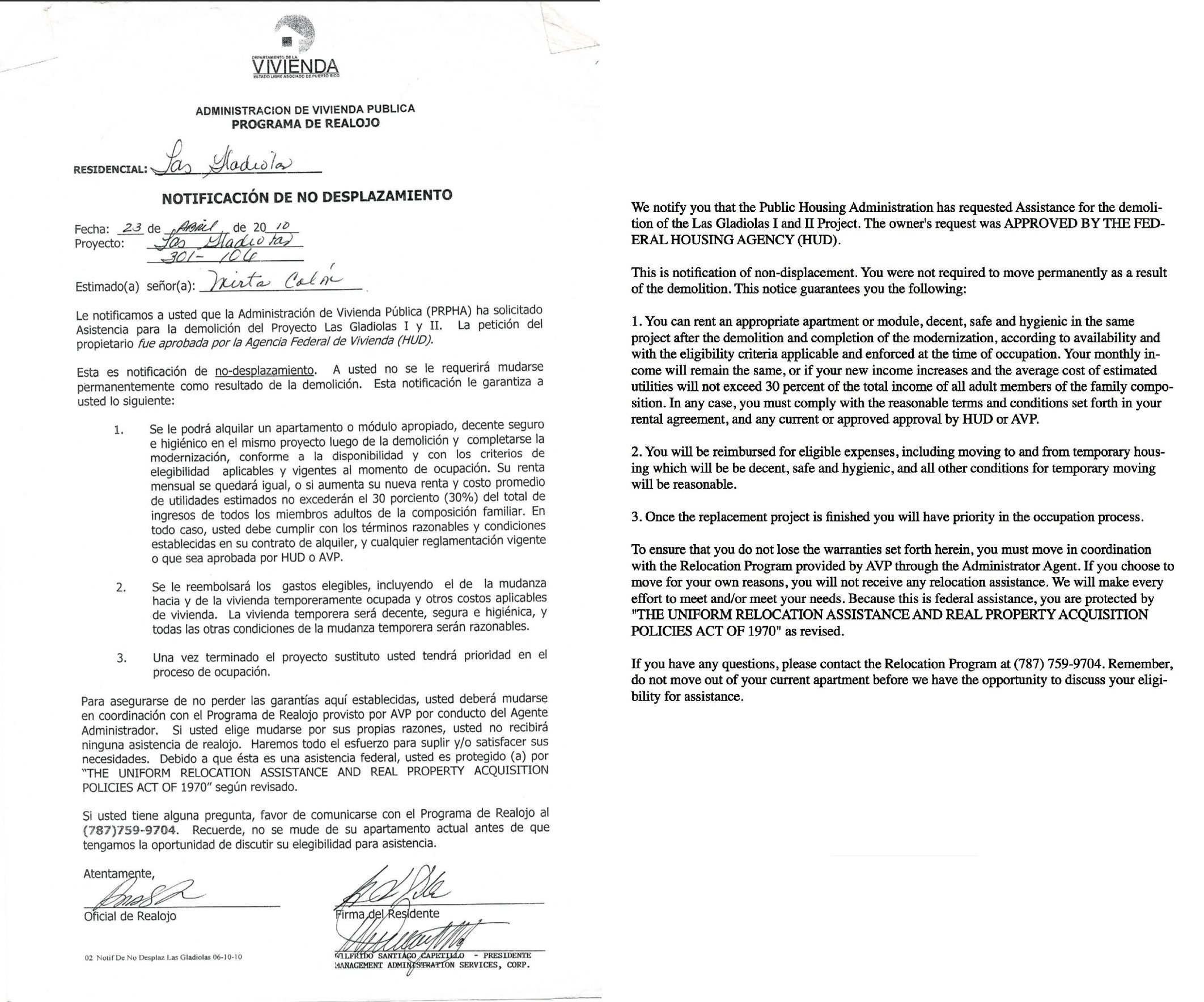

Eviction orders were first distributed at Las Gladiolas in 2002 and again in 2006 following the approval of AVP’s application to demolish the towers by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) that February. The December 2010 removal of 250 remaining residents was the culmination of a class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of residents. It alleged that HUD’s approval to demolish Las Gladiolas on February 2, 2006, due to “no reasonable and cost-effective plan for repairs or ‘modernization’” was unlawful given that agency had not adequately consulted with residents prior to evictions. In 2008, American Management, one of the firms contracted by the AVP in charge of maintaining the complex, said that the buildings had “serious structural problems that put the health and safety of tenants at risk.” A July 2010 ruling issued by the United States Court of Appeals, First Circuit in Boston deemed the evictions lawful. The court finalized its decision that October, ending an impressively organized, decade-long effort led by residents of the complex, attorneys, and local activists that stood in the way of the housing authority’s attempt to free up the land for redevelopment.

***

The mass eviction that took place at Las Gladiolas is one of many that have been carried out by AVP in recent decades. Puerto Rico currently maintains 327 public housing complexes. Lists of demolished projects, scattered across the archives of Puerto Rican newspapers, include:

- Crisantemos I and II, San Juan (Demolished in 1996).

- Las Acacias, San Juan (Demolished in 2000, 250 families displaced).

- Puerta de Tierra, San Juan (Demolished in 2015, over 400 families displaced).

- Las Gladiolas, San Juan (Demolished in 2011, over 400 families displaced).

- José Gautier Benítez, Caguas (Demolished 2015, over 400 families displaced).

- Felipe Sánchez Osario, Carolina (Demolished in 2012, over 300 families displaced).

In an interview with El Vocero in August 2017, over six years after the demolition of Las Gladiolas, Housing Secretary Fernando Gil Enseñat told the paper that “most of [Puerto Rico’s] projects are in privileged real estate spaces.” The newspaper cited the public housing complex Nemesio Canales near Plaza Las Américas, the largest shopping mall in the Caribbean. Also mentioned were the Manual A. Pérez and Ernesto Ramos Antonini projects near the Mall of San Juan in Río Piedras, as well as the Luis Llorens Torres houses, located within walking distance of the beach in Santurce. “It’s a mine of gold,” says Colón, referencing the location of the former Las Gladiolas just down the road from the headquarters of Banco Popular. “It’s land that everyone would like to own.”

Projects in states of “advanced deterioration” set to for demolition include Los Álamos in Guaynabo, Las Amapolas in Río Piedras, Villa Monserrate in Aguas Buenas, Torres de Sabana in Carolina, Los Cedros in Trujillo Alto, Los Peña in San Juan, and Rafael Hernández Kennedy in Mayagüez. Dos Ríos and Alturas de Ciales in Ciales were marked for demolition in June due to damage caused by Hurricane Maria. AVP did not respond to multiple requests for a complete list of public housing residences set for demolition by the agency.

In June, Rodriguez was quoted saying that the agency will not construct any more public housing in Puerto Rico. Instead, AVP has plans to “update existing public housing” and grant contracts through the investment of private capital to construct mixed-income housing in the place of demolished residences. According to the agency, the construction of these projects marks a paradigm shift in Puerto Rico’s approach to housing assistance. The new strategy seeks to eliminate the stigmas attached to public housing while “creating communities where different people with different incomes can live in the same environment, and class differences are erased.” However, the small number of units available at the new developments raise questions about the government’s intentions in its pursuit of the new model.

Two mixed-income housing projects on the sites of the former Puerta de Tierra and José Gautier Benítez residences are currently under construction through contracts won by St. Louis, Missouri-based developer McCormack Baron Salazar (MBS). The firm was previously granted a contract by the AVP to construct Renaissance Square. Funding was committed through a partnership between MBS, HUD, Citi Community Development, and Hunt Capital Partners. MBS boasts the use of “public dollars to leverage private equity, resulting in a $35.5 million investment in the transformation of a formerly vacant public housing site”. The projects, under construction in San Juan and Caguas, will contain 174 and 438 units (in Caguas, a 200-unit residence for senior citizens and the remaining 238 for other residents). Only a percentage of these units will be available to low-income residents. At Renaissance Square, only 14 former residents have qualified for a new apartment despite a 2010 “non-displacement agreement” with AVP guaranteeing the 110 residents of Las Gladiolas who agreed to temporary relocation priority placement in a percentage of the 140 units available to the public.

In 2018, AVP completed another development containing far fewer units than the original at the site of the former Felipe Sánchez Osario residence. At the time of its inauguration, officials indicated that the 153 new units would house only a portion of some 300 former residents. Many of those residents were elderly or disabled, and only 39 units comply with the Americans With Disabilities Act. At the former Las Acacias residences, there are currently 85 public housing units available in reconstructed walk-up apartments called Puerta de Tierra II, less than half of the number of units available at the original complex. The agency also plans to construct mixed-income housing through private-public funding partnerships on the sites of Los Álamos, Crisantemos, Torres de Sabana, Los Cedros, and Los Peña. At least one vacant lot, identified as Plot 55 in Santurce, has been identified as a site where the agency plans to construct new affordable housing.

***

Officials say that displaced families have the right to choose housing alternatives “established under Section 18 of the Federal Housing Law of 1937 and its regulations 27 CFR part 970.” Public housing residents are either relocated to existing units or are offered relocation through Section 8 vouchers authorizing rental subsidies on the private market. Those who opt for relocation through Section 8 and those assisted by the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program (LIHTC) will be eligible to access new units, but the reduction in the number of apartments available is likely to force many former public housing residents to remain on the private market.

Colón and other former tenants say that the housing voucher system is challenging to navigate. It is more than possible for displaced families in need of assistance to fall through the cracks without proper support. According to Colón, the agency only stepped in to assist elderly residents at the time of evictions following public pressure from the community. Beginning in 2017, those who wished to return were subjected to a tedious, multi-part pre-approval process carried out by McCormack Baron Management. The company requires criminal background and credit checks on top of compliance with state and federal guidelines. Daniel F. Acosta, Project Director and Senior Vice President of MBS, explained that families might not qualify if a renter has a criminal record because MBS wants “a healthy community to make progress.” His statement obscures Puerto Rico’s history of criminalizing its low-income residents. Another requirement includes a request for updated documents every 120 days throughout the approval process to remain eligible for placement at the units. It is unclear whether displaced residents from other demolished public housing projects will be guaranteed future placement at new developments.

***

Currently, there are more than 18,000 Puerto Rican families on a waitlist to access public housing. The total is a nearly 6,000-person reduction from the number reported by the agency in 2017, which officials attributed to families losing “interest” or leaving the island in search of alternatives. In June, AVP Administrator William Rodriguez that the agency had identified six lots in the San Juan metropolitan area where the construction of new affordable units could begin before the summer of 2020, including the pending demolition site of Torres de Sabana in Carolina. Rodriguez estimates that the projects will result in the completion of 1,000 new units, while another 1,400-2,000 units currently vacant due to infrastructure problems will be renovated. The new projects will draw from a combination of investment from private firms, federal income tax credits, and the allocation of $400 million from Community Development Block Grant — Disaster Relief funds (CDBG-DR), according to the agency.

Recent reports indicate that the next wave of CDBG-DR funds authorized in Puerto Rico, passed in July just before demonstrators ousted Governor Ricardo Rosséllo Nevares from office, will prioritize the construction of affordable housing and incentivize investment in impoverished areas that the federal government has declared “opportunity zones.” These zones, which make up more than 95% of Puerto Rico’s territory, aim to attract investment from developers through tax breaks drafted as part of the 2017 Republican-passed Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The next wave of nearly $1.5 billion (only a fraction of the $20 billion approved by HUD) in CDBG-DR funds and a following $8.2 million in disaster mitigation funds (CDBG-MIT) come attached to updated FEMA flood maps that will likely require the relocation of low-income communities while simultaneously allowing large developers to invest in the construction of businesses (such as shopping centers and hotels) on the same land.

“A bunch of developers are coming to the island because of the CBDG funds. And they’re talking about the ‘reconstruction’ of the country because they’re so good,” says Colón, her voice laced with sarcasm. Large developers profit through the allocation of federal tax credits passed on to renters assisted by the LIHTC program and, in many cases, contribute very little money to projects like Renaissance Square. Hunt Captial Partners, which acted as a tax credit syndicator for the development of Renaissance Square, writes that the project “was awarded $25.7 million in federal LIHTCs” from the Housing Finance Authority of Puerto Rico (Autoridad para el Financiamiento de la Vivienda, AFV). An additional $7.8 million in funding for the development was provided by AFV and HUD, with Citi Community Capital financing construction.

Hunt Capital Partners also acted as the tax credit syndicator for Bayshore Villas (the project nearing completion on the site of the former Puerta de Tierra). Caribbean Business Times reports that the private-public partnership cost $41.3 million and was “financed with $27.8 million in private capital provided by Alden Capital Partners and Citibank NA through the LIHTC program administered by the [AFV].” HUD provided only $13.5 million, while Citi Community Capital provided a construction loan. The firm notes that “the area directly south of Puerta de Tierra is part of the Bahia Urbana revitalization initiative, which is a 15-year, $1.5-billion waterfront initiative that will redevelop 87 acres along the San Juan ports.”

Meanwhile, Freddie Mac, the federal government-sponsored mortgage lender responsible for the facilitation of various LIHTC subsidies granted to investors (also a partial recipient of a $200 billion government bailout following its role in the 2008 financial crisis), provided a “$37.5 million LIHTC equity investment” for MBS’s 238-unit project in Caguas through a partnership with RBC Captial Markets’ Tax Credit Equity Group, according to a 2019 report. The 200-unit project reserved for the elderly at the same site received a $28.9 million investment through the partnership. “Investors have been reluctant to return to Puerto Rico following the hurricanes of 2017, and Freddie Mac’s investment epitomizes their commitment to add liquidity to the LIHTC market to ensure much-needed housing is delivered in underserved areas,” RBC’s managing director Eric Moody told Housing Wire in January.

In San Juan, the former residents of Las Gladiolas remain vocal. Those who have managed to relocate to Renaissance Square say they’ve dealt with instances of discrimination by private management, are subject to strict community guidelines that appear to criminalize low-income renters, and feel unsafe in a community supposedly designed with the security of residents in mind.

***

In 2001, Colón lost her job as a prison social worker. She had two young children and could not pay rent. Desperate for a solution, she went to AVP intending to apply for public housing. “I explained to him that it was an emergency, that I had to leave from where I was, and that I had two children and no food benefits.” Upon completing her application, she asked a state worker for a timeline on approval. The official laughed in her face. Colón had arrived with all of the proper documents in hand as a result of her professional background. The AVP official had not expected this. “You have to go through processes where people humiliate you, where it seems that they are giving you something that belongs to you,” she says. “As a citizen, you have the right to these services. If state workers have those jobs, it’s because there are people that have needs.”

Colón, who in the past two decades has earned a reputation as a force to be reckoned with in the organizing community, walked into El Capitolio in Old San Juan and asked to speak with a senator she had met through a function at her children’s school. She found herself in an apartment at Las Gladiolas the same day. “At 1:30 p.m. that afternoon, I was placed in public housing. At 2 p.m., I had an apartment. How can you explain this?” she asks. “I was in a difficult situation. How sad for that person who didn’t have those resources, that human capital. Do you understand?”

Colón’s placement at Las Gladiolas was the beginning of her education as a housing rights organizer. “Necessity is the mother of invention. There was work to do,” she says, explaining that she never intended to lead a fight against the government. She currently serves as the president of Asociación de Residentes Gladiolas Renace, a coalition of former tenants. This March, she was awarded for her work as a community leader at the Cumbre Comunitaria por la Recuperación de Puerto Rico (Community Summit for the Recovery of Puerto Rico) alongside four other organizers. The plaque presented by then-Governor Ricardo Rosséllo Nevares sits discarded on the living room sofa. She acknowledges it with a mixture of pride and laughter. That the Rosséllo administration would present her with such an award is ironic. The administration, following in the footsteps of the administration of Governor Alejandro Garcia Padilla, endorsed the mixed-income housing developments that displaced hundreds of residents from Las Gladiolas and elsewhere.

“Las Gladiolas was first a private apartment complex,” says Colón. While a resident, she spent nearly a year unemployed studying the history of the complex before her 2010 removal. Senators, professional artists, and other wealthy elite occupied the units. “There was a misuse of funds by the developer that left the first part of Gladiolas occupied, and the second unfinished.” The situation provided an opportunity for the housing authority to purchase the property and convert it into 676 units of public housing, altering the reputation of the neighborhood.

“We have to accept that the community faced social disadvantages,” she says. Before 2001, Colón had never lived in public housing. Family members critical of her entrance into the system offered to take custody of her two dependent children, fearing for the family’s safety. She spent her first weeks at Las Gladiolas avoiding interaction with neighbors. “People don’t want to remember this, but it was real — Gladiolas was the largest drug servi-carro in the metropolitan area. All of those professionals from offices in the area would get into their Mercedes’ and their BMW’s and they would drive in and out to get their stuff.” The economic development on the Milla de Oro was just beginning to arrive. “I lived closed up, in confinement. Same as you see here,” she says, waving her hands around the small space. “I got used to being locked up. I’ve always lived like this.”

***

As a resident, Colón recalls having to adjust to her new reliance on the housing authority. She rented on the private market for years and wasn’t used to having help. “There, they even gave you the paint if you had to paint the apartment,” she says, explaining how the system benefits residents. Colón did not intend to stay and had job offers coming up within 3-4 months of her arrival. She eventually landed positions with GAR Housing and Housing Promoters, placing her on the payroll of two of the 11 management companies then-contracted by the AVP to maintain various residences. At work, she began to realize that it was a popular opinion among management and housing officials that Las Gladiolas should be demolished. “These are people who say we’re ungrateful. Then, they allow things to deteriorate because then they can hold us responsible,” she notes. No later than one year after her arrival, in 2002, eviction orders were distributed among residents accused of living in apartments illegally. Management was allowing conditions to deteriorate to the point that apartments were becoming unlivable. “The elevators were so broken that the only way to fix them was to throw the old ones away and get new ones,” she says. The community protested, demanding better conditions. Each time, they presented complete proposals for projects to improve life at Las Gladiolas. A plan for new elevators was one of many ignored by management, which Colón indicates at this point was a different company, S&P Management, which is still under contract with the AVP.

When the demolition was finally approved, residents stalled the process with a lawsuit. Faculty with the Legal Assistance Clinic at the University of Puerto Rico took on the case while academics attempted to investigate the cost to renovate each apartment. Officials reported that the cost to repair the units would have totaled nearly $81 million. One senator divided the number by 676 to estimate $320,000 per apartment, although a precise cost estimate does not appear to be publicly available. According to a case study completed by Hunt Capital Partners, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) recently committed $200 million to rehabilitate only 750 units of affordable housing in Puerto Rico. The high cost and the small number of units raise questions as to why the cost to renovate the apartments at Las Gladiolas was considered too high. The community lost its lawsuit on March 5, 2008. Attorneys appealed the case at a First Circuit court in Boston, delaying demolition for the next two years.

***

In hearings held during an October 2017 visit from a U.N Special Rapporteur on Puerto Rico’s housing crisis, Colón says that the term “bulldozing” was used to describe repeated efforts by the government to evict low-income communities. “Our community was ‘bulldozed’ every single day so that these agencies could achieve what they wanted. People couldn’t take it anymore.”

As time passed, the severity of the removal efforts increased. “Things were done mafia-style. They were creating that environment of fear and uncertainty,” she says. Sewage and water systems at the towers would often break down. A lack of access to flowing, potable water renders citizens officially homeless, leaving families with children who refused to vacate their apartments vulnerable to custody threats. Sometimes, management shut off the water because the AVP was not properly reimbursing the company for the cost of utilities. In the absence of responsive landlords, residents would throw their hoses across the towers so that those without water would have access to the service. Authorities claiming to be concerned about the drug trade amplified the instability with civil rights abuses such as police raids conducted in the middle of the night so that residents would not have time to ask for warrants.

A video from February 2005 shows police kicking in the door of an apartment during a raid at Las Gladiolas. The police chief tells reporters that the department is trying to “save the families from drugs” and that “people who don’t live here don’t have the right to be here.” He justifies the raids with the language used in the 1990s under Mano Dura Contra el Crimen, adding, “We are going to stay here until we get control and maintain control over these towers and people are safe to live here.” Residents reported incidents where officers stole money and clothing. According to Colón, police carried out raids out two to three times a week. Elderly residents and children occupied many of the apartments. “They broke down doors without warrants. Once, they tried to break my door down, and I asked to see it. They didn’t have one.”

Colón’s own story counters the popular narrative that Las Gladiolas was a danger to its residents. One afternoon, she ran into a man who had been one of her cases in prison in the hallway. He was surprised to see Colón, and upon learning that she lost her job, he assured the former social worker that she and her children would be welcome and safe. “I found out later that he was the one who was leading the drug operation,” she says, but the interaction opened doors, and in the following months, Colón met other neighbors who had also been her cases in prison. “I was strict, but I was also fair to my clients. They had trust in me,” she shares. As a result, she was loved at Gladiolas upon arrival and didn’t know it. “If I had been shameless and I had abused my power and authority, I wouldn’t have been able to live there.”

***

As conditions worsened, Colón began to call the press. Residents would live without light or water for 3-4 days at a time. “If you can believe it, the process to fix the light took less than 5 minutes. When press came, not even 10 minutes later, the guy to fix the light would arrive.” Where other strategies failed, officials began to buy tenants out. At one point, Colón fell in her apartment and found herself in a wheelchair. There was no water and no working elevator in her building. She lived on the 8th floor, forcing members of the fire department to drag hoses up the stairs. A group of firefighters was called to carry her downstairs when she had doctor’s appointments. “I called Channel 2, and a reporter filmed the 10-12 employees carrying me up and down.”

At that moment, the company contracted to administer Las Gladiolas was MAS Corporation. “The entire board met with me the following day,” she says. Management gave Colón an empty 4-bedroom apartment on the 1st floor. Within three days, with employees working double shifts, the company installed new windows and pipes. They painted the walls and cleaned the floors. “They would say to neighbors, ‘You need a refrigerator and a heater, right? Well, I’m going to buy a refrigerator and a heater. I have apartments, one in Llorens and another over here…which one do you want? You have to leave.’” An official from the AVP called Colón out of a public assembly and offered her a house, a car, a cell phone, and a job. “I don’t know how to drive, and I’ll never know how,” she says. A political shakeup had resulted in the cancellation of GAR Management’s contract, leaving Colón and 300 employees without work. She estimates that half were residents of public housing. She was offended by the offer and told him, “I had a job, and your administration threw us out on the street.”

As officials began to realize the scope of Colón’s strength as an organizer, she faced attacks in the press. A reporter claimed that Colón owed $10,000 in rent to the agency. “It got to the point that they were making commissioned reports about me for speaking out about the well-being of my community,” she recalls. She attributes the strategy to the man who was AVP administrator at the time. At a hearing in a federal court, Colón filed a formal complaint against the administrator. Lawyers had to kick her under the table to prevent her from speaking when the administrator informed the courtroom that he did not have a college degree.

***

In June, Colón sits in a chair in the middle of her corner unit at Renaissance Square. Unpacked boxes line the walls. The award plaque she received from Rosséllo in early March sits discarded on a chair at the kitchen table. MBS began handing out apartments to approved applicants in December 2018. Hurricane Maria delayed the construction process on various units, leading to their rapid completion before the arrival of residents. Colón discovered shortly after moving in that some of the pipes in her bathroom were filled with concrete. “They broke down the wall in my closet, the wall in the bathroom. They covered the expenses; otherwise, I would have sued them. I have respiratory problems, and they did not accommodate me. They know that my respiratory problems are serious. I also have a granddaughter with severe allergies.”

Residents have reported plenty of issues with the new apartments, including mold growing in cabinets left exposed to humidity. At Colón’s unit, inspectors came just before her move-in date to verify that it complied with federal disability regulations. “They had to knock down an entire wall because it wasn’t built up to standard with the regulations. Mine was the last apartment to be filled. It did not seem new at all,” she says, noting that the appliances in the kitchen were dirty and that workers left the apartment covered in dust. “A friend came over to clean twice this week, and there is still dust. If I were to open the windows, there would be mountains.” Colón suspects that the quick completion was to prevent loss of revenue following Maria. Workers accidentally left papers in her apartment detailing a multitude of problems reported by residents in other units. “It’s a business. I don’t want to be the person who points out all of the negatives, but I’ve spoken with friends who sleep with the front door open because it will not close.”

Colón and other community members who opted to relocate to the private market spent years dealing with discrimination from landlords. “There were instances where community members were trying to rent apartments, and neighbors would ask the landlord not to because it would devalue the property. They called us ‘delinquents’ and ‘the people from the houses.’” At one point, Colón (who no longer works due to health issues) was forced to rent an apartment for $1,300 a month, of which she paid 30% through Section 8. In 2016, six years after the distribution of non-displacement agreements, AVP informed former residents that a private developer would construct the apartments through a public-private alliance. The following year, the agency told residents that the parameters to qualify for apartments had changed. Not everybody who signed a non-displacement agreement would be eligible, as Renaissance Square is not considered public housing. AVP does not list the development as one of the properties it maintains. “If it isn’t paid in 30 years, the complex belongs to the developer,” Colón explains.

As of late June, only 14 families who signed non-displacement agreements have relocated to Renaissance Square. Sixty-eight families filled out applications following an orientation held by management in December 2018. Of those, 65 qualified in an initial round. Many families did not make it through the pre-qualification process set by McCormack Baron Management or have moved on out of necessity. According to MBS’s Acosta, only 56 units are available to public housing residents, forcing the remainder of those displaced from Las Gladiolas who qualify to rent through private-market subsidies.

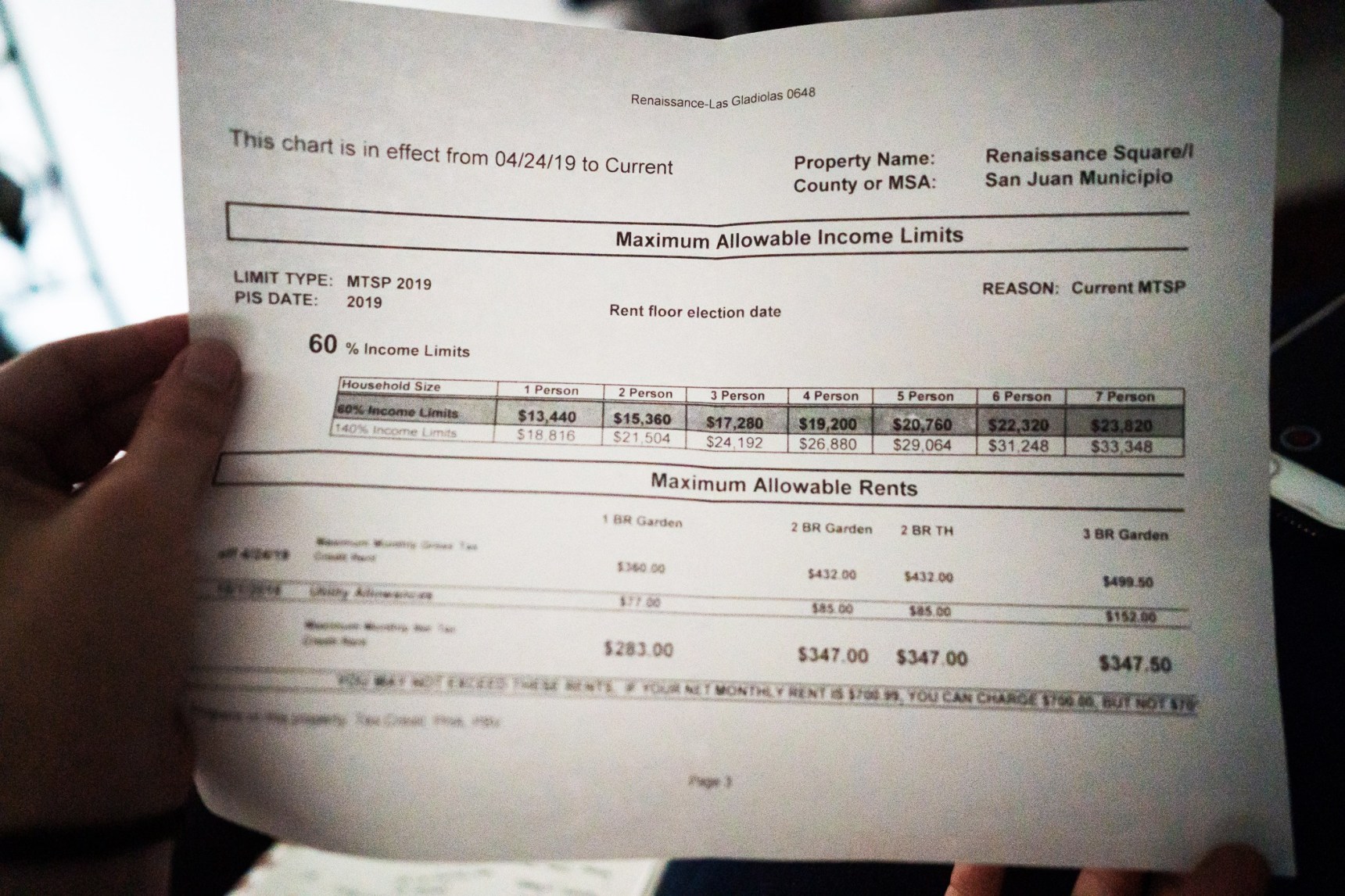

Colón qualifies for subsidized rent but was not informed at the time she signed her non-displacement agreement that much of the complex would be tax-credit based. Residents who are eligible through Section 8 pay 30% of the monthly cost of rent. Units at the complex go for monthly rates of $625 for one-bedroom, $730 for two bedrooms, and $800 for three bedrooms. A chart given to potential residents displaying the maximum allowable income limits for the LIHTC program sets the threshold for a single-person household at $13,440 annually. Someone working 40 hours a week at Puerto Rico’s $7.25/hour minimum wage will make $13,920 annually and will not qualify for the program. “The oldest person in my community goes over the limit by $3 per month and doesn’t qualify. People who are retired and receive Social Security income and a pension — $1,200 total — $600 from one and $600 from the other, also don’t qualify,” says Colón.

“This contrasts with the speech of empowerment that the government throws at us — that this is an opportunity to become independent. We try to rise up. The same system holds us down.” Colón gets by each month by budgeting her $739 pension. She worries that in the coming years, she will no longer qualify to live in her community. “The other thing that you see on the chart is the annual income restriction of 140%. I was accepted to live here with my $739 income. However, six months into the lease, I start getting a slightly higher pension. After one year, it will surpass the 140%. If I stay quiet, they’ll accuse me of fraud.”

***

In March, former Las Gladiolas resident Hommy Montalvo Andino, 41, opens the door to his building and greets Colón with a hug. The aroma of cooking rice fills the hallway outside. “Look how beautiful,” says Colón, starting at the newly-constructed units from the stairwell. Inside Montalvo’s apartment, the air is cool and inviting. Units at Renaissance Square come with pre-installed air conditioning (a luxury in Puerto Rico, where the cost of electricity per kilowatt doubles the average in the United States). “I’m afraid to see my electric bill,” says Colón, who glances around curiously. She has yet to move into her apartment, which she expects to receive in May. The units are filled with amenities. Nearly all of the English-language press surrounding Renaissance Square raves about the luxuries provided to low-income residents at the new apartments. Air conditioning, energy-efficient appliances, climate-resilient roofs and windows, even solar panels installed above units — are featured in descriptions of the development, of which Colón, Montalvo, and others are the guinea pigs. The two walk around the apartment while Montalvo explains the features to Colón, who is excited to return to the community she calls home.

“When it came down, it was like removing a veil,” said architect Álvarez‐Díaz & Villalon about the demolition of the towers in a July 2017 article published by Curbed — a trendy, NYC-based real estate and urban design blog owned by Vox. “There was this wonderful community hiding behind it that was ignored for so many years.” The article addresses the lower number of units, describing the “faceless” towers of Las Gladiolas while arguing that the lower-density units “will have a closer relationship with the surrounding environment.” Álvarez-Diaz is also responsible for the design of Bayshore Villas, constructed on the site of Puerta de Tierra. The property was originally home to El Falansterio, the first public housing project in Puerto Rico. The apartments, constructed in 1937, are described by MBS to have become “an example of the detrimental effects of concentrated poverty”. The firm argues that Puerta de Tierra, built in its place, “became an obstacle to the stabilization and proposed redevelopment of the district and an obstacle to the success of its own families.” A former resident of Puerta de Tierra responsible for organizing the community told People Live Here that the decision to demolish the residence displaced 482 families.

Colón is naturally critical of the idea that the displacement of hundreds of families and the construction of affordable luxury units equals a better, stronger community. “This was the solution — to integrate the different social classes. I have nothing against the architects. But, an architect can’t pretend to be a social worker or a private psychologist. They need to understand that a “pretty” community is not necessarily a better community.”

Montalvo is a third-generation resident of Las Gladiolas. McCormack Baron Management initially denied his application to receive a unit at Renaissance Square. Colón went up to bat for him, forcing management to reconsider. “They said he was evicted from a previous apartment for not paying, which was unfair,” she explains. Montalvo clarifies that he pays rent when he receives his Social Security check each month. If the check arrives late, he’s forced to pay rent late. The former resident is disabled as a result of negligence by the management companies responsible for the maintenance of Las Gladiolas. Residents would attempt to fix the elevators on their own. One day while Montalvo was working on an elevator, it fell, striking him on the head in its descent. He was fortunate enough to survive the incident but developed epilepsy as a result of his injuries and cannot work.

Montalvo’s grandmother signed the non-displacement agreement guaranteeing the family’s relocation to Renaissance Square in 2010. She did not live to see the completion of the complex. Montalvo relocated at least three times in the 6-year gap between their consent to leave Las Gladiolas and the opening of the development. Now, Montalvo qualifies for his apartment as the first of the 56 public housing residents allowed access to the units. He is also one of the former tenants who alleges instances of discrimination by private management.

Asked to describe the incidents, Montalvo details an encounter that took place a few days earlier. “I was leaning with my back against one of the tables downstairs,” he says, pointing in the direction of common areas set up in the courtyard. “My back is messed up from the epileptic attacks. The manager left the office and told me I couldn’t sit like that.” Montalvo obliged and sat on the ground instead, which the manager also indicated was a problem. “My back is in critical pain. If there were back supports on the benches, I could sit there. I’m grateful to be here but feel pressure from the administration. I think they have a problem with us because we put up a fight to get here.”

He launches into another story about how management, which advertises the community as “smoke-free,” forces tenants who smoke cigarettes to leave the property. “There are cameras set up everywhere for our ‘security,’” adds Colón. She finds the idea of security particularly ironic, given that residents who need to smoke at night are forced to cross an unlit street to smoke in an empty parking lot in the middle of Hato Rey. The street lights do not function at Renaissance Square because the contractor installed the light connections in the wrong place. “They’ve been in a back and forth with PREPA (Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority),” she says. The main street of Renaissance Square, Calle Luna, is still not listed on GPS as of September 2019 as a result of this issue. Montalvo indicates that the road is open to the public. It does not have gates, and anybody can drive through to access Barrio de las Monjas, just behind the complex.

Earlier that month, management threatened to fine a former resident who tried to smoke on the side of the complex still under construction. “They warned her she would have to pay $50. She told them, ‘I’ll have to give it to you in quarters because I’m broke,’ he says. Management has also reprimanded Montalvo for “yelling” to communicate with guests entering from downstairs because the intercom system connected to his doorbell does not work. “You need to tell them that this is unacceptable,” pushes Colón. “I do,” he responds. “I put it in writing so that there’s evidence, and it still happens.” Montalvo recalls walking into the management office wearing shorts one afternoon. The woman inside told him that he couldn’t come into the office dressed “like that” — a bizarre concern, given that Renaissance Square is a residential housing complex located on a tropical island. “I went in later that day and said before I walked in that I want to pay rent, but I can’t because I’m in shorts. The woman looked at me like she was furious. We try to keep up with the rules like don’t leave that door open, close the gate, or don’t play music too loud. I don’t understand what the deal is.”

***

Colón and others who lived through police raids at Las Gladiolas are suspicious of the idea of “security” and feel that the cameras are set up to surveil residents who might be breaking an extraordinarily strict set of rules handed out to tenants approved to live at the complex. Colón recalls a meeting held on May 27 in which low-income residents described that they felt “trapped inside a jail.” Residents are required to sign the “Reglas de la Casa” before move-in and are subject to eviction if they repeatedly violate the contract. The list is comprehensive and at times, condescending. “The resident will not use or permit the use of his unit in a way that could be annoying or disturbing other residents, or in a way that would be illegal, immoral, inappropriate or that would cause damage or damage the reputation of the property,” reads the first of an 18-page document signed by residents alongside lease agreements. On another page that describes the eviction process, McCormack Baron Management writes that the company will attempt to assist those in violation of the rules, but that “the final solutions to your problems must come from you.”

“This is a public street. If someone comes to visit me, I have to open my door, which is practically on the sidewalk. According to the contract I signed, management can discipline me for standing in my doorway conversing with someone,” says Colón. The document states that lobbies, hallways, and passages should not be used “for any purpose other than entering and leaving the apartment.” Later, it specifies that “sidewalks, entrances, hallways, and stairs should not be used for any other purpose than to enter and exit.” On another page, the contract states yet again that front doorways are to be kept clear to maintain “an attractive community.”

Residents are held responsible for the actions of their visitors and are subject to fines, as well as the possible termination of lease agreements should visitors break the rules. The contract appears to criminalize residents and their guests who violate these terms, stating that management will automatically file a police report about anyone removed from the property. “They had the audacity to say, ‘Since I have cameras, I can see who the person went to visit. The tenant is responsible for their visitor(s) and that they comply with the contract’,” says Colón. Other rules appear to reference Las Gladiolas and other public housing projects considered to be “dangerous.” These include statements that “The resident shall not…maintain or allow any industry, business, trade, profession, of any type…within the unit” (in reference to the drug trade) and the oddly specific “Firearms, pellet guns, compressed air guns, knives with blades larger than 4 inches, hunting knives, swords, karate weapons (i.e., Fuji sticks), firecrackers and cherry bombs are PROHIBITED.” The administration also writes that “under no circumstances” will they tolerate “any act of graffiti/writing on the walls or vandalism.”

Colón suspects that an English speaker wrote the rules and later had them translated into Spanish. The theory might partially explain several insensitive statements that appear to be directed at low-income Puerto Ricans. Management writes that residents may not allow “unpleasant or unusual odors to be generated from his apartment in such quantities that permeate other apartments and become annoying or offensive to other another resident or residents.” It specifies that “normal cooking odors, generated ‘normally’ and ‘reasonably’” are welcome. Residents are not allowed to hang items such as signs, flags, or photographs from their balconies. Christmas lights must be mounted “in good taste.” Residents are not allowed to keep mops or brooms on their balconies. This statement, in particular, reads as a direct reference to Puerto Rico’s public housing projects, many of which had sinks on the balconies where residents would keep supplies. “There is a limit of four plants per unit on patios. Stairwells are supposed to be kept clear, yet neighbors have told me that in other buildings, there are plants all over. Most of them belong to a resident who pays market-rate. The management says nothing,” alleges Colón.

Other rules that target low-income renters include a policy that labels anyone who pays rent late more than three times within 12 months a “chronic offender.” If a tenant’s checks are returned for insufficient funds more than twice, management will no longer accept them as payment. This policy will impact residents like Montalvo, whose ability to pay rent on time is often entirely out of his control. The development boasts ample community space, but children who wish to use the recreation area must own proper footwear. The park closes at 6:00 p.m., just around the time that working parents arrive home with their children from school. Residents who use the community center are required to pay a deposit that is only refundable if the room is sufficiently clean. The original contract states that the smart keys given to residents are replaceable for a fee of $200. Colón raised this issue to management and MBS’s Acosta at the May 27 community meeting, where officials allegedly admitted that the cost was too high. “They were surprised and said that it was a mistake. Now, they cost $45,” she says.

Reglas de la Casa Renaissance Square

***

“Back to the issue of security,” says Colón in mid-September. She and two other former Las Gladiolas residents sit in the living room, discussing their concerns about management. “I have to use my glasses to work the smart key correctly. If the key displays a red light, I have to wait until it goes away to try again. Let’s talk about security and this key when it’s nighttime someone can easily rob me while I’m standing there trying to open the door.” The other women nod in agreement. “If the keys lock themselves, we have to pay to get them unlocked after business hours.” Colón says the group’s concerns about a lack of access to the parking lots were brushed off by Acosta, who allegedly told her that marking the spaces along the main roads as “reserved” was unnecessary and that non-residents taking the spots was “more of a Boricua cultural issue.” Colón indicates that many of the low-income tenants do not own cars and do not have access to the gated parking lots. “Many of these residents are elderly or disabled. They also go grocery shopping. Why not give them a beeper so they can unload cargo into their kitchens?” Those who do own a vehicle must provide documentation of a valid driver’s license and an up-to-date vehicle registration sticker. The policy effectively prohibits access to residents who cannot afford to renew their tags, which is required annually in Puerto Rico.

Zoraida Báez Rodríguez, 62, sits on Colón’s sofa. She moved to Las Gladiolas in 1973. Her family relocated to Renaissance Square in January after Báez qualified to pay around $150 a month as a public housing resident. In February, Baéz began receiving Social Security income, which she reported to the woman who served as manager at the time. “She told us we would figure it out later,” says Báez. Management did not provide the family with updates. By May, the manager had been promoted, and another woman took over the position. She asked the family for documentation of the new income and submitted it to the firm for approval. Then, McCormack Baron Management accused Báez of committing fraud.

Colón explains that the leasing process for public housing guarantees qualified residents access to the unit for 12 months regardless of income changes. That policy is not in place at Renaissance Square, leading to confusion for residents transitioning into the private market where income changes lead to problems. “How is it possible that due to the manager’s negligence, this family is struggling to survive?” she asks. Báez sighs, explaining that she has no idea where her family will go if they’re unable to pay rent. “It’s hard. There aren’t many options.”

Management initially asked the family to leave, but upon pressure from Colón agreed to offer Báez a unit at market rate, or $730 a month. If she accepted, management would not report her. Colón says that Báez would be paying only $333 a month under public housing with the addition of her Social Security income, a payment calculated by management. She specifies that in a normal scenario, AVP would work with Baéz to raise her payment and keep her in the system until the end of her lease. Now, if Báez were to lose her social security income and re-qualify for public housing, she would go to the bottom of the waitlist. The family does not qualify for food stamps and also has medical bills. “After the cost of utilities, they’re paying over $1000,” says Colón.

Colón pulls up her own electricity bill on her phone, indicating that for September, she will owe at least $230. As a public housing resident, she received subsidized electricity. The bill is more than what she pays in rent. According to architect Álvarez-Díaz & Villalón, apartments “sport photovoltaic solar panels to offset traditional electricity costs and minimize the community’s environmental footprint.” Former Las Gladiolas resident Milagros Colón Rodríguez, 62, says she recently noticed that the solar equipment on apartment rooftops has yet to be connected. However, the panels on the roof of the building that houses management and the community center are allegedly functioning. “I get sick if I’m in the heat,” says Colón, who paid nearly $403 in electricity her first month at Renaissance Square. “I don’t want to die in the heat, but I do die every time the bill comes in.” In June, Colón indicated that she was in the process of filling out paperwork for a subsidized reduction on the cost of electricity for the medical equipment that keeps her alive. She shares that her water bill is only slightly higher than it was before, as low-income Puerto Ricans are eligible for subsidized water across the board.

“It is so peaceful sleeping in bed with air conditioning. I enjoy better living conditions! Who doesn’t?” says Colón. Simultaneously, she describes feeling generally unwelcome and locked inside her brand new apartment. “We lived in a place where rooms were falling apart. But, I could speak to my neighbor outside. We lived entrapped in these enclosed spaces but never had any problems.”. Colón often chooses not to leave at night as she feels unsafe on the dark streets of the complex. The outdoor spaces at Renaissance Square are often empty despite claims that its design fosters a safe, well-integrated community. “I come back to my apartment underneath the camera out there. They are not making us any safer. They’re watching us come and go.”

“If Gladiolas still existed, I would walk right back into my old apartment,” says Rodríguez, who moved to Las Gladiolas in 1982 and lived on the 16th floor. She describes having a view of the entire city. “The apartments were more comfortable. I felt safer there, surrounded by my community.” Both Colón and Báez echo this sentiment. “It might sound absurd, but I felt safer at Gladiolas,” adds Colón. “Even with the shootings, at least I knew where to duck and hide. Entering my living room from the side of the road is not the best feeling.”

Colón refuses to stop organizing. As of mid-September, there are still five unoccupied Section 8 apartments. The 14 residents from Las Gladiolas are not allowed to form a coalition until management fills the units. “We will continue to fight. It’s harder here — we used to go around with a bullhorn to ensure that messages got to every single resident. But of course, here you can’t make noise. You can stand in the door to receive people, but you can’t stand outside in groups.” Colón has begun receiving emails from Fideicomiso de la Tierra del Caño Martín Peña/G8 Inc. The non-profit advocates on behalf of communities in the area. Las Gladiolas, despite its highly organized status, was never invited to join.

Colón knows that her activism stands in the way of the elimination of public housing on an island where a large portion of residents struggle to survive. “I fight for my son,” she says. Only two of Colón’s five remaining children live in Puerto Rico. Her son, unable to find work in his 30s, left for the United States with a 5-year-plan intending to return to the island with enough income to survive and assist his mother. He died of an asthma attack alone in Chicago in 2016. “What is happening to my family is the portrait of what’s happening to thousands of families on this island,” she says. Colón is well aware that she and other struggling residents bear the weight of the island’s $129 billion debt, an economic situation they played no part in creating. “I feel anger and pain. In a normal situation, my son wouldn’t have left the country, and he would be alive today. People decided for us,” she says, referring to the island’s colonial status and the Puerto Rico Financial Oversight and Management Board, set up to restructure the debt and impose austerity measures that adversely impact Puerto Ricans dependent on public services. “We’re the ones suffering the consequences. It’s the same people who support this privatization who think that we’re lazy and that we don’t work. In reality, this is an essential public service. Where are poor people going to live in this country?”

Elia Gran, Flor Cruz, & Deva Montaner contributed translations to this article.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $34,000 in the next 72 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.