“It is much easier not to struggle, to give up and take the path of the living dead. But if we want to live, we must struggle.” –Oscar López Rivera, 1991

“It is much easier not to struggle, to give up and take the path of the living dead. But if we want to live, we must struggle.” –Oscar López Rivera, 1991

Wednesday, May 29 will mark 32 years since Puerto Rican activist Oscar López Rivera was arrested and later convicted of “seditious conspiracy,” a questionable charge that Archbishop Desmond Tutu has interpreted to mean “conspiring to free his people from the shackles of imperial injustice.”

Today, 70-year-old Oscar López Rivera, never accused of hurting anyone, remains in a cell at FCI Terre Haute, in Indiana. Supporters around the world continue to seek his release, most recently by asking US President Barack Obama for a commutation of his sentence. Similar pardons granted by President Truman in 1952, President Carter in 1979, and President Clinton in 1999, were the legal bases for the release of many other Puerto Rican political prisoners.

Since all of Oscar López Rivera’s original co-defendants have since won their release, he is famous in Puerto Rico as the longest held Independentistapolitical prisoner. Supporters are planning a range of events across the island for the upcoming week, as they mark this dubious ‘anniversary.’ Among those calling for his release is Javier Jiménez Pérez, the mayor of his hometown of San Sebastián, Puerto Rico, and a supporter of statehood.

Upside Down World interviewed Dylcia Pagán, one of López Rivera’s co-defendants, by telephone from her home in Loíza, Puerto Rico, where she continues to work in support of other political prisoners. Asked why the US government should release López Rivera now, after 32 years, Pagán told Upside Down World:

“Oscar should be free because he is an incredible human being, an artist, and a man that has a lot to give society in both the US and Puerto Rico. He has never even been accused of committing an act of violence. This conviction for ‘seditious conspiracy’ is what they’ve used against all of the Independentistas. The US claims to believe in democracy and human rights, but Oscar’s continued imprisonment is a clear violation of both.”

“Oscar should be free because he is an incredible human being, an artist, and a man that has a lot to give society in both the US and Puerto Rico. He has never even been accused of committing an act of violence. This conviction for ‘seditious conspiracy’ is what they’ve used against all of the Independentistas. The US claims to believe in democracy and human rights, but Oscar’s continued imprisonment is a clear violation of both.”

Pagán adds: “Oscar has served his time with dignity and has contributed to the lives of other prisoners. He deserves to be home in Puerto Rico, just like all of us.”

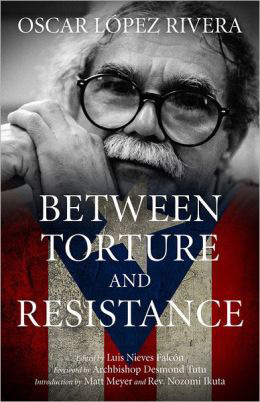

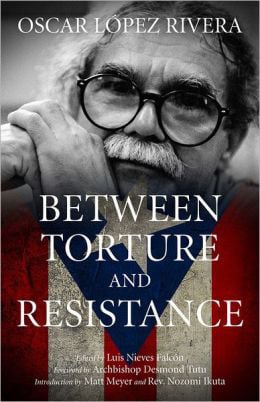

Between Torture and Resistance

“I was born Boricua, I will keep being Boricua, and will die a Boricua. I refuse to accept injustice, and will never ignore it when I become aware of it.” –Oscar López Rivera, 2011

With public support continuing to build for Oscar López Rivera’s release, PM Press has just published an important book, entitled Between Torture and Resistance, timed well to amplify López Rivera’s voice at this critical time. The book bases its text upon letters López Rivera has written over the years to lawyer and activist Luis Nieves Falcón, as well as letters to and from many family members during his imprisonment. This new book examines the broader political significance of López Rivera’s case, while providing an unflinching look at how imprisonment and draconian policies like solitary confinement and no-contact visits affect prisoners and their loved ones.

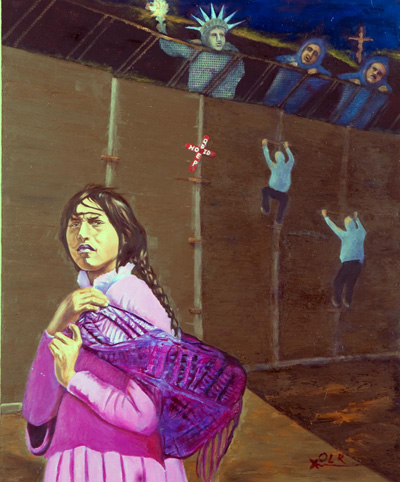

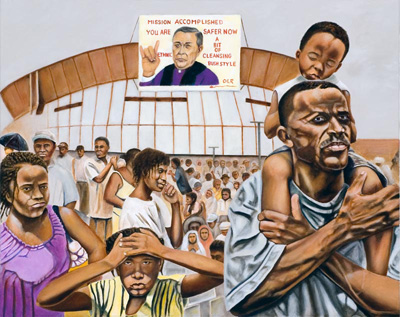

Perhaps nothing illustrates López Rivera’s character better than how he refers to himself with the lowercase use of the letter ‘i,’ in order to deemphasize the individual with respect to the collective. His letters offer a view into the mind of an extraordinary person. Reading first-hand in Between Torture and Resistance about the range of abuses that López Rivera has survived while in US custody may cause readers nightmares, but his accounts are a badly-needed reality check for anyone unfamiliar with the typically brutal treatment of US political prisoners. As Reverend Ángel L. Rivera-Agosto, executive secretary of the Puerto Rico Council of Churches comments, the book “is a powerful testimony, born from the cold bars of imprisonment, as a sign of today’s injustice and lack of freedom and respect for human rights.”

The chapter entitled “Life Experiences: 1943-1976,” offers a glimpse into the early years of Oscar López Rivera, born on January 6, 1943, in Barrio Aibonito of San Sebastián, Puerto Rico. At the age of fourteen, he moved with his family to the US and eventually graduated from high school in Chicago in 1960. In a 1981 interview, López Rivera’s mother, Mita described this initial move, reflecting: “My husband came looking for a better environment and it was not to be found here. We have to work harder, it’s colder, [there is] more humiliation, more racism for us…We live humiliated by the Americans…We suffer in this country.”

After working several different jobs to help support his family, in 1965 the government drafted López Rivera into the Vietnam War, which ultimately “awakened previously unexperienced feelings about Puerto Rico. First, the Puerto Rican flag became a symbol of important unity among the Puerto Rican soldiers…Second, Oscar began to question his role in such a terrible war. Why did they have to kill people who had done nothing to them? Why kill people who appeared to have things in common with Puerto Ricans themselves? He began to question the actions of North American imperialism in that Southeast Asian country, and the role of Puerto Ricans in the imperialist wars of the United States. These two seeds—cultural nationalism and anti-colonial struggle—begin to germinate in Oscar’s mind in Vietnam, and ripened later in his life,” writes Luis Nieves Falcón.

After working several different jobs to help support his family, in 1965 the government drafted López Rivera into the Vietnam War, which ultimately “awakened previously unexperienced feelings about Puerto Rico. First, the Puerto Rican flag became a symbol of important unity among the Puerto Rican soldiers…Second, Oscar began to question his role in such a terrible war. Why did they have to kill people who had done nothing to them? Why kill people who appeared to have things in common with Puerto Ricans themselves? He began to question the actions of North American imperialism in that Southeast Asian country, and the role of Puerto Ricans in the imperialist wars of the United States. These two seeds—cultural nationalism and anti-colonial struggle—begin to germinate in Oscar’s mind in Vietnam, and ripened later in his life,” writes Luis Nieves Falcón.

López Rivera’s politicization continued after serving in Vietnam, when he returned to Chicago. After working with the Saul Alinsky-influenced Northwest Community Organization, in 1972, he co-founded the Pedro Albizu Campos High School, an alternative school controlled directly by Puerto Ricans. Nieves Falcón writes that here “Oscar articulated a powerful vision of how alternative schools can challenge the essentially racist system of mainstream US education.”

In 1973, he co-founded Juan Antonio Corretjer Puerto Rican Cultural Center and in 1975 helped establish Illinois’ first Latino Cultural Center. López Rivera participated in some of the Young Lords’ activities, but he was not a member of the group. In addition, he worked on other issues, including racial discrimination in hiring and working conditions, confronting landlords about housing conditions, and improving hospital conditions and medical services for the most vulnerable. Luis Nieves Falcón comments that Lopez Rivera’s “civil activism between 1969 and 1976 clearly evidenced his genuine and significant effort to use every possible route of change within Chicago’s existing official structures.”

In 1973, after joining the National Hispanic Commission of the Episcopal Church, López Rivera publicly supported Independentistas imprisoned in the US for attacks on the Blair House (the Presidential guesthouse) in 1950 and on the US Congress in 1954. In the early 1970s, several armed clandestine groups formed in Puerto Rico and carried out actions to protest the US occupation of Puerto Rico. At this time, the Armed Forces of National Liberation (FALN) formed inside the US and from 1974-1980 claimed responsibility for multiple bombings, mostly in New York and Chicago, of military, government and economic targets. The FALN said they meant for their actions to publicize US colonization of Puerto Rico and to demand the release of the same imprisoned Independentistas that Oscar López Rivera and other community activists had been publicly supporting.

In response, the US government held Grand Jury investigations, ‘fishing’ for intelligence on the FALN, in 1974 and from 1976-1977. The government jailed several members of the National Hispanic Commission of the Episcopal Church for refusing to cooperate with the Grand Jury, including López Rivera’s brother, Jose. With Oscar López Rivera expecting to be the Grand Jury’s next target, he and three other close associates went underground, where López Rivera remained from 1976 until his subsequent arrest in 1981.

Convicted of ‘Seditious Conspiracy’

Convicted of ‘Seditious Conspiracy’

“This is not a trial. It is not even a kangaroo court.” – Oscar López Rivera, speaking at the 1981 court proceedings.

Oscar López Rivera’s legal team at the People’s Law Office, explains on their website:

“In 1980, eleven men and women were arrested and later charged with the overtly political charge of seditious conspiracy — conspiring to oppose U.S. authority over Puerto Rico by force, by membership in the FALN, and of related charges of weapons possession and transporting stolen cars across state lines. Oscar was not arrested at the time, but he was named as a codefendant in the indictment…In 1981, Oscar was arrested after a traffic stop, tried for the identical seditious conspiracy charge, convicted, and sentenced by the same judge to a prison term of 55 years. In 1987 he received a consecutive 15 year term for conspiracy to escape–a plot conceived and carried out by government agents and informants/provocateurs, resulting in a total sentence of 70 years.”

At Oscar López Rivera’s 1981 trial, he took a position similar to that of his co-defendants at their earlier trial: he declared the trial illegitimate and refused to present a defense or pursue an appeal. However, López Rivera did make an eloquent statement, reprinted in Between Torture and Resistance:

“Given my revolutionary principles, the legacy of our heroic freedom fighters, and my respect for international law—the only law which has a right to judge my actions—it is my obligation and my duty to declare myself a prisoner of war. I therefore do not recognize the jurisdiction of the United States government over Puerto Rico or of this court to try me or judge me.”

Later, at his 1987 trial where the court convicted him of “conspiracy to escape,” López Rivera took a similar stance, and in his statement, also reprinted in the new book, he elaborated further on the precedent set by anti-colonialist international law:

“Colonialism, dear members of the jury, is a monumental injustice according to the norms of civilized humanity and a crime under international law. According to United Nations Resolution 2621, the continuation of colonialism in all its forms and manifestations is a crime that constitutes a violation of the charter of the United Nations, Resolution 1514 (XV), the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples….No nation, ladies and gentleman, has the right to take over another nation. The military invasion and occupation of Puerto Rico clearly depicts the rapacious and voracious nature of the United States government, with the armed forces, rifles, and cannons it used to subjugate a people into submission and reduce a nation of one million inhabitants to a commodity for the bartering of human beings. For 89 years, this nation, conquered by force—the Puerto Rican people—have been denied their basic rights to self-determination and independence.”

‘Spiritcide’ and the Torture of Imprisonment

“The memory of our pain deserves to be appreciated, remembered, and never denied.” —Oscar López Rivera, 1997

Following his 1981 conviction, the government first held López Rivera at FCI Leavenworth in Kansas, until 1986. Upon arrival, Luis Nieves Falcón writes that “the majority of the prison guards were waiting for him. They surrounded him and verbally assaulted him. They repeatedly stressed that they didn’t want him there; that he was a dangerous terrorist and the place for him was Marion: an even higher-security prison, regarded among prison guards as the right place to eliminate terrorists.” Despite a clean record at Leavenworth and a 1985 report by his jailers that “he demonstrated favorable adjustment and maintained positive relations with the staff,” López Rivera became the target of an FBI entrapment scheme, involving a fabricated escape plan. On June 24, 1986, just days after the government formally accused him of planning to escape, he received a disciplinary transfer to the notorious federal prison in Marion, Illinois.

Following his 1981 conviction, the government first held López Rivera at FCI Leavenworth in Kansas, until 1986. Upon arrival, Luis Nieves Falcón writes that “the majority of the prison guards were waiting for him. They surrounded him and verbally assaulted him. They repeatedly stressed that they didn’t want him there; that he was a dangerous terrorist and the place for him was Marion: an even higher-security prison, regarded among prison guards as the right place to eliminate terrorists.” Despite a clean record at Leavenworth and a 1985 report by his jailers that “he demonstrated favorable adjustment and maintained positive relations with the staff,” López Rivera became the target of an FBI entrapment scheme, involving a fabricated escape plan. On June 24, 1986, just days after the government formally accused him of planning to escape, he received a disciplinary transfer to the notorious federal prison in Marion, Illinois.

During the court proceedings for the ‘escape’ charges, held from September 1986 to February 1988, prison authorities held López Rivera in solitary confinement at MCC Chicago. Following his conviction and sentence of 15 years, authorities transferred him back to Marion, where he stayed until 1994. The new book features his reflections upon his living conditions during this period. López Rivera writes:

“i use the word ‘spiritcide’ to describe the dehumanizing and pernicious existence that i have suffered…i face, on the one hand, an environment that is a sensory deprivation laboratory, and on the other hand, a regimen replete with obstacles to deny, destroy or paralyze my creativity…i am locked up in a cell that is 6’ wide and 9’long, for an average of 22 ½ hours a day…Living in these conditions day after day and year after year has to have an adverse effect on my senses. i don’t have access to fresh air or to natural light because when i turn off the light in the cell to sleep, the guards keep the outside lights on and light enters the cell…Day and night i hear the roaring of the electric fans, whose noise is so strident that when I don’t hear them, i feel disoriented.”

Later in the same letter, López Rivera explains how he has survived:

“i know that the human spirit has the capacity to resurrect after suffering spiritcide. And like the rose or the wilted leaf falls and dies and in its place a newer and stronger one is reborn or resurrects, my spirit will also resurrect if the jailers achieve their goals…My certainty lies in my confidence that i have chosen to serve a just and noble cause. A free, just, and democratic homeland represents a sublime ideal worth fighting for…i am in this dungeon and the possibility that i will be freed is remote, not to say impossible, under conditions equal to or worse than caged animals, under spiritual and physical attack, but with full dignity and with a clean and clear conscience.”

In 1994, authorities transferred López Rivera to a new federal prison in Florence, Colorado that soon became as notorious as Marion was, for its own human rights abuses. After over a year of good behavior at Florence, authorities transferred him back to Marion after denying his request to be transferred elsewhere. Even though Marion had officially become lower security than before, following his transfer back, López Rivera reported that conditions had become worse.

Perhaps most chilling is his account of getting an operation for a hemorrhoid condition three days after his mother had passed away. Authorities had denied his request to attend the funeral. Within hours of the procedure, the area operated upon became infected, with his fever finally reaching 102.7 degrees. At this point, instead of giving him antibiotics as he immediately requested from the medical staff, authorities accused him of stealing the needle used for a blood test. The authorities cruelly withheld the antibiotics. Two days later, as the still untreated infection got even worse,

Perhaps most chilling is his account of getting an operation for a hemorrhoid condition three days after his mother had passed away. Authorities had denied his request to attend the funeral. Within hours of the procedure, the area operated upon became infected, with his fever finally reaching 102.7 degrees. At this point, instead of giving him antibiotics as he immediately requested from the medical staff, authorities accused him of stealing the needle used for a blood test. The authorities cruelly withheld the antibiotics. Two days later, as the still untreated infection got even worse,

“They released me from the hospital and returned me to the hole. The jailers that took me were racing wheel chairs. Every turn made me feel as if someone was cutting me with a razor. i got to the cell and was preparing to clean up the blood. A lieutenant came in and said they were going to cuff me…According to him i had stolen the needle and immediately passed it to an accomplice who took it away…They searched me from head to toe. Blood was running down my legs, and here he was passing a metal detector on my rear. To punish me, they did not allow me to use the sitz bath or give me medications.”

It was not until 10:00 pm, the following day, López Rivera writes “that they gave me the sitz bath and the antibiotics…An hour later, my body responded and I was able to use the toilet—an incredibly painful ordeal”

In 1998, after 12 years in total isolation, authorities transferred López Rivera to FCI Terre Haute, in Indiana, where he remains today. Once there, he was finally able to have contact visits and other new ‘privileges,’ which increased his quality of life. Despite these improvements, the People’s Law Office reports that prison authorities imposed a special condition requiring him to report his whereabouts every two hours to prison guards. Even though this condition was initially scheduled to end after 18 months, it still continues today, over 14 years later.

Since 1999, authorities have barred the media from interviewing López Rivera, “in spite of policy allowing for media interviews of prisoners, in spite of allowing media interviews of other prisoners, and in spite of having allowed Oscar to be interviewed many times previously, without incident. Each rejection has used the identical, unsubstantiated excuse that ‘the interview could jeopardize security and disturb the orderly running of the institution,’” writes the People’s Law Office, noting further that “since 2011, the government has extended this ban beyond media, rejecting requests by New York elected officials to meet with Oscar.”

The Struggle Continues

“They will never be able to break my spirit or my will. Every day I wake up alive is a blessing.” – Oscar López Rivera, 2006

In 2011, the denial of parole to Oscar López Rivera outraged the leaders of Puerto Rico’s political and civil society, who publicly denounced the ruling. One critic, Puerto Rico’s non-voting U.S. congressional representative, Pedro Pierluisi, said, “I don’t see how they can justify another 12 years of prison after he has spent practically 30 years in prison, and the others who were charged with the same conduct are already in the free community. It seems to me to be excessive punishment.”

In response to the parole denial, 1984 Nobel Peace Prize winner Archbishop Desmond Tutu joined Nobel Laureates Máiread Corrigan Maguire of Northern Ireland and Adolfo Pérez Esquivel of Argentina, to send a letter to US President Barack Obama expressing their concern about his parole hearing. The letter cited how “testimony was permitted at that hearing regarding crimes López Rivera was never accused of committing in the first place, and a decision was handed down which—in denying parole—pronounced a veritable death sentence by suggesting that no appeal for release be heard again until 2023.”

Following the parole denial, López Rivera declared in a public statement to supporters:

“We have not achieved the desired goal. But we achieved something more beautiful, more precious and more important. And that is the fact that the campaign included people who represent a rainbow of political ideologies, religious beliefs, and social classes that exist in Puerto Rico. This to me represents the magnanimity of the Boricua heart—one filled with love, compassion, courage and hope.”

Today, López Rivera and his support campaign are focusing their efforts on a a letter-writing campaign asking US President Barack Obama to pardon him (view/download a suggested letter). There is a strong precedent for this strategy. In 1952, President Harry Truman commuted the death sentence of Oscar Collazo. In 1977 and 1979, President Jimmy Carter pardoned Andrés Figueroa Cordero, Rafael Cancel Miranda, Lolita Lebrón, Irving Flores and Oscar Collazo.

Today, López Rivera and his support campaign are focusing their efforts on a a letter-writing campaign asking US President Barack Obama to pardon him (view/download a suggested letter). There is a strong precedent for this strategy. In 1952, President Harry Truman commuted the death sentence of Oscar Collazo. In 1977 and 1979, President Jimmy Carter pardoned Andrés Figueroa Cordero, Rafael Cancel Miranda, Lolita Lebrón, Irving Flores and Oscar Collazo.

In 1999, President Bill Clinton pardoned Oscar López Rivera’s co-defendants Edwin Cortés, Elizam Escobar, Ricardo Jiménez, Adolfo Matos, Dylcia Pagán, Luis Rosa, Alberto Rodríguez, Alicia Rodríguez, Ida Luz Rodríguez, Alejandrina Torres, Carmen Valentín, and Juan Segarra Palmer. President Clinton offered to release López Rivera on the condition that he serve ten more years in prison. However, because Clinton did not extend that offer to two other Independentista prisoners, López Rivera did not accept the offer. In 2009 and 2010, those two other prisoners won their release on parole, making López Rivera the last co-defendant still imprisoned today, even though Clinton’s offer would have ostensibly released him in 2009.

Dylcia Pagán, pardoned in 1999, says that after 32 years of imprisonment, the time is now for President Barack Obama to pardon Oscar López Rivera. Asked to compare today’s political climate to that in 1999, Pagán is optimistic and says the movement is “alive and well,” with popular pressure continuing to build in support of López Rivera. “Hopefully, Oscar will be home by Christmas.

The new book, Between Torture and Resistance, concludes with a final thought from Luis Nieves Falcón:

“The best tribute we can extend to Oscar is to continue to fight every day, with yet greater determination, for his release. Every day that Oscar remains in prison is another reminder of the hypocrisy and absurdity of the US government’s talk of human rights in light of its colonial rule. In the strongest possible terms, let us raise our voices to denounce this abuse and demand freedom for Oscar López Rivera.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.