As anti-immigrant policies and rhetoric increase in the U.S., more immigrant families – especially ones with at least a member who is undocumented – are shying away from applying for any form of public benefits. With the Trump administration pushing rule changes to expand the definition of who is a “public charge” and ineligible for permanent residency, a mix of fact and rumor is pushing families away from accessing the help they need for stability – and often when they are entitled to the support.

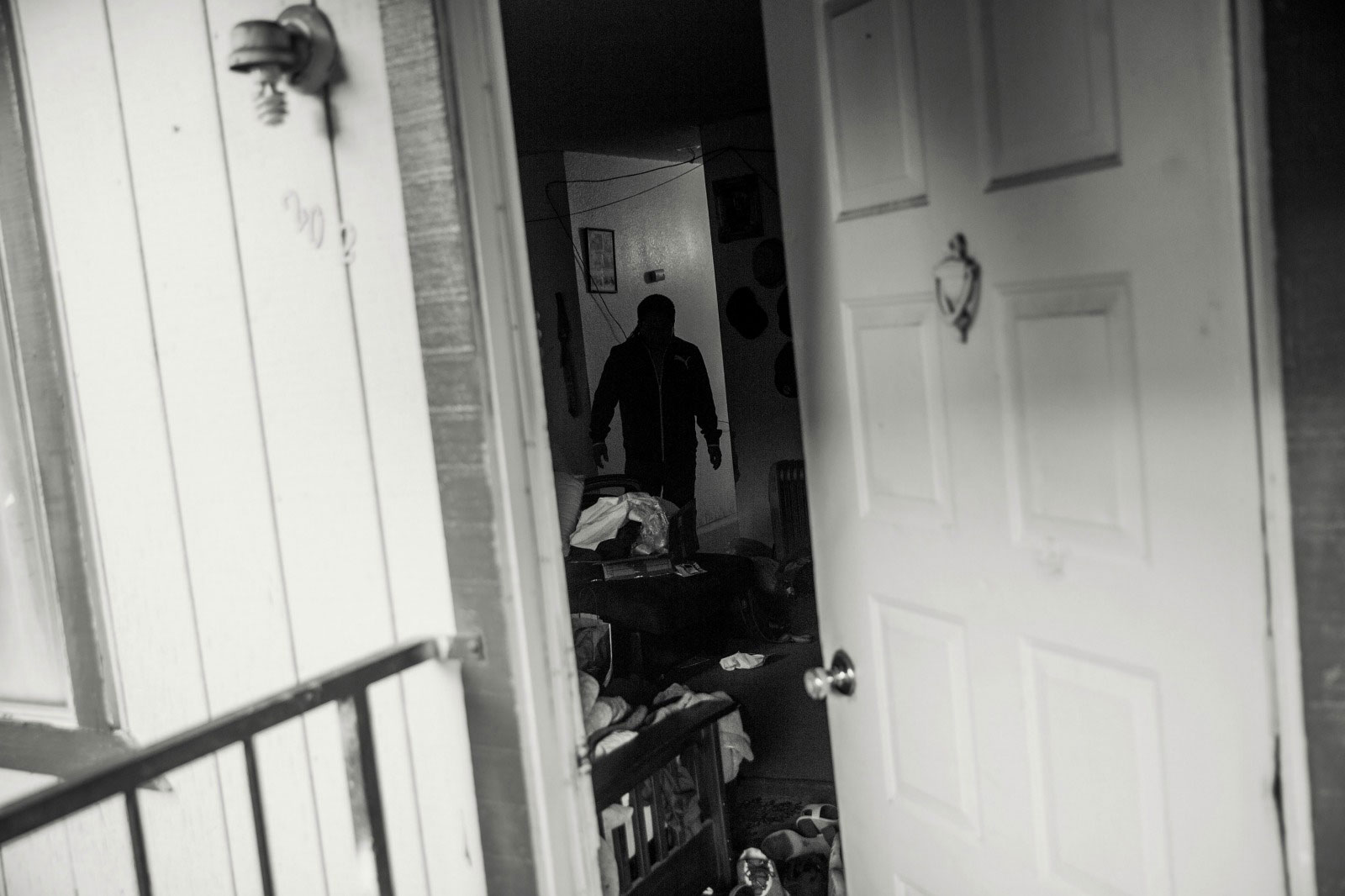

“I missed the opportunity of getting housing at one point,” says Laura, a 35-year-old Boulder, Colorado, resident. “I had just started the process of getting separated from my husband. I was with my three children. We were staying with relatives for a few months while I was looking for employment and housing.”

Laura, who migrated without documents from Mexico in the late 1990s and only wanted her first name used because of safety concerns, has a degree in film production. She eventually did find a job with a nonprofit arts’ organization that puts on stage shows about the lives of immigrants. It was worthwhile work that made her happy, but it didn’t pay much. She struggled to find an affordable apartment for her family.

“I applied to a housing program in Boulder, and I qualified to get a townhouse” she says.

But then the rumors started flying that the Trump administration was changing the definition of “public charge,” so that immigrants who applied for public benefits, or whose children accessed benefits, would be ineligible to apply for a change in their residency status. Among Laura’s circle of friends, the idea took root that anyone who accessed benefits “would be priorities for removal,” a term used by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to define the sorts of individuals that Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents should prioritize when seeking out undocumented people to deport. Laura, a Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipient, was spooked.

“Those are very scary thoughts when you have children and don’t want to be separated from them,” she says. “I thought it was too risky to get the housing assistance. So, I turned it down.”

Instead, she looked for a home on the open market. She found one, but she had to pay for it without help. Now, almost all of Laura’s after-tax income goes to paying rent.

* * *

Laura wasn’t quite right about the rule changes, but she wasn’t entirely off-base in her fears.

In 2018, the Trump administration formulated a change to the definition of public charge, an administrative rule dating to the late 19th century that allowed immigration authorities to deny visas or residency to those deemed likely to become financial burdens on the state.

Historically, public charge was defined as being about cash benefits – welfare programs such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children in the mid-century and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) after the reforms of the 1990s. It had never before been interpreted to include emergency medical, nutritional or housing assistance for people.

Stymied by Congress in its efforts to rein in immigration, the Trump administration set its sights on a series of bureaucratic rule changes, including slowing the approval of visa applications and expanding the definition of public charge – which could be implemented absent new legislation. The early iterations of the change, leaked to advocacy organizations in early 2018, expanded the definition to include a supplemental nutrition program for women and children, Head Start and subsidized school lunches. It also allowed the benefits of children who are U.S.-citizens to be halted when their parents apply for a change of residency status.

Faced with a chorus of outrage, from medical workers to chambers of commerce, the administration backpedaled slightly. The version they finally put up for public comment was somewhat less draconian, advocates say. It included fewer benefits in the dragnet and no longer explicitly targeted U.S.-citizen children.

Organizations working for immigrants and anti-poverty initiatives believe that even in this streamlined form, the proposed rule change would be utterly destructive, allowing immigrants’ use of food stamps, Medicaid and housing programs to be counted against them in the process that could lead to U.S. citizenship. The administration even discussed including the Children’s Health Insurance Program for immigrant kids, though it backed off of this. And it did include TANF if a U.S.-citizen child receives the benefit in an immigrant family, and if that is the entire family’s only source of income.

In a way, the exact list of benefits included in the rule change is secondary to the fear that such a revamp is guaranteed to unleash. Rumors have spread fast and furious through immigrant communities in recent months. As a result, even before any of the rule changes go into effect, providers are already seeing clients stampeding away from benefits.

“We have heard that families have either disenrolled from programs or decided not to sign up for programs, including Medi-Cal in California, or SNAP benefits, even if the children are eligible,” says Antionette Dozier, senior attorney with the Western Center on Law and Poverty in Los Angeles. “There are a number of organizations who are already seeing the fear that has taken root and the harm that is occurring as families choose not to accept these necessary benefits. Not feeding their kids, kids not getting health care or housing assistance.”

Natalia Jaramillo, a spokesperson for the National Domestic Workers Alliance, says the proposed changes have created a “perception that undocumented folks shouldn’t apply for their children.”

In Jacksonville, Florida, Marivi Wright is the lead community outreach coordinator for the Wolfson Children’s Hospital’s Player Center for Child Health. To her team’s horror, they have seen more and more immigrant families refusing Medicaid.

“They think they’ll get deported if they apply for help, even if their children are U.S. citizens,” she says.

Wright mentions one family whose newborn child was placed in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.

“They were,” she says in amazement, “afraid to go to the mailbox to retrieve their [Medicaid] card. We have to regain the trust of the family – the child was born here. He’s a U.S. citizen. He’s entitled to care.” Another family also refused Medicaid for their newborn who became sick shortly after they brought him home. They ended up having to take him to the emergency room because they did not have private insurance and weren’t enrolled with a pediatrician.

Laura, in Colorado, has foregone applying for Medicaid and food stamps for her three children.

“I felt it would put me at risk, for sure,” she says. “Most people I know stay away from benefits if they are undocumented, because no one wants to raise that flag.”

She suspects the fear extends to those with legal status, too: “People who have documents, it’s unfortunate that they’re afraid they’re going to take their documents away from them.”

* * *

Sonya Schwartz, senior policy attorney at the National Immigration Law Center (NILC), is frustrated by the way the rumors have outrun the reality. She says the administration can’t implement these changes until it has read and responded to the comments filed during a legally mandated public comment period. And thanks to a huge outreach effort by immigrant-rights and public health organizations, more than 266,000 comments were filed.

Since the comment period closed in late 2018, only about 60,000 of those comments have been read. Once all the comments have been processed, the administration can publish the rule changes in the Federal Register. But even then, those changes can’t take effect until at least 60 days after publication.

Done properly, this process could take years. However, Schwartz and other immigrant rights attorneys believe the administration will try to ram through the changes, ignoring the overwhelming number of comments from health care providers and community members. USCIS head Francis Cissna, who opposes a speedy revamping of the public charge rule, is thought to be on his way out, and news outlets are reporting he will likely be replaced by someone who supports the change.

Schwartz is anticipating litigation, with cities, states and organizations, such as NILC, arguing that the new rules will arbitrarily hurt immigrants and undermine public health.

They will lay out how these changes take the country in the opposite direction to that proposed by the congressionally mandated Child Poverty Study, a 600-page tome published in February. It urges Congress to prioritize evidence-based policies that would cut child poverty rates in half within 10 years.

The Child Poverty Study concluded this could only be done by including immigrant families in anti-poverty measures, and by expanding benefits systems to include documented immigrants. Nationally, 1 in 4 kids has at least one immigrant parent – and in California that number is 50 percent, rising all the way to 80 percent in some counties. By contrast, some say, the public rule change is pretty much guaranteed to increase the child poverty rate.

“The sad thing is feeling because you’re an immigrant and don’t have status, your life and family is worth less than the rest of the people, and you’re not worthy of assistance,” says Laura.

“It’s a great injustice. Our taxes support the benefits of many Americans. And on the moral side, we have an obligation to other fellow human beings, no matter where they come from.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.