“A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.”

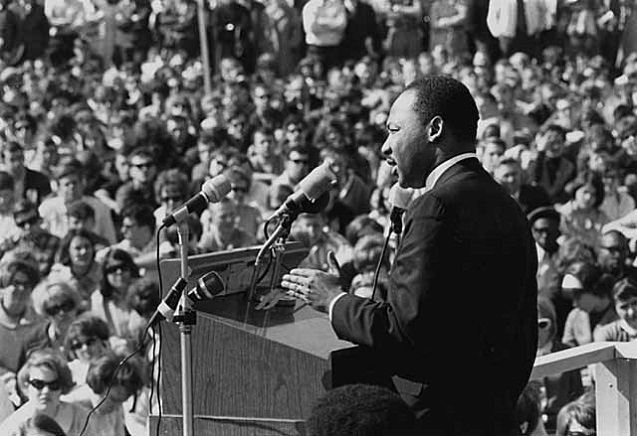

Democracy is dead. It has always been an afflicted creature – hobbling about – wounded at its very being. An enslaving disposition corrupted the United States before it matured. Its spiritual death was foretold, but the nation refused to hear the black voices crying out in the wilderness. At the Riverside Church, the Holy See of liberal Protestantism, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. – born in the bosom of the black Baptist church – prophesied: “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.” And he was martyred a year later on April 4, 1968.

A year before the racist, materialist and militaristic ax cut King down, he warned the nation of its demise. The now infamous “A Time to Break the Silence” speech at the Riverside Church on April 4, 1967, was a stern warning against the maladies of the American spirit – materialism, racism and militarism. The year between the Riverside speech and his assassination proved to be a radical one. As though he was racing against death’s chariot, King accelerated his critique of the United States and took up more radical tactics.

Bloody engagement in Vietnam had launched an anti-war movement. An unrepentant pacifist since her student activism days at Antioch College, Coretta Scott King came out against the Vietnam War months before Dr. King. In the spring of 1965, King began to voice opposition to the immoral war. In sequestered black spaces like Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood, Howard University and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) 1965 convention, King called for a cease-fire and a negotiated peace. In response, the SCLC Board of Directors censored King and issued a statement distancing them from King’s anti-war position. Fearing reprisal from the Johnson administration, King’s staff and comrades encouraged him to avoid making public statements on the war.

“We all thought he was out of his mind. It was just too risky. It was the right thing to do, but it would jeopardize the (civil rights) movement.”

On January 6, 1966, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) issued a policy statement condemning the “Racist Imperialist War” in Vietnam. Rabbi Balfour Brickner recalled a meeting a week or so before King’s Riverside speech. Rev. William Sloane Coffin, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, Rev. Walter Wink, Brickner and King were among the attendees. “We all thought he was out of his mind.” Brickner shared. “It was just too risky. It was the right thing to do, but it would jeopardize the (civil rights) movement,” Brickner reflected over coffee in 2005.

King linked the war against poverty to the war in Vietnam and was summarily dismissed by The New York Times and every other major newspaper in the country. He was called “outdated” and “doing a disservice to his cause” by making those connections between materialism and militarism. Other civil rights leaders issued rebukes of King as well.

With keen economic analysis in one hand and the Bible in the other, King preached that the federal government should devote billions of dollars to ending poverty in the richest nation in the world. Economic justice was essential to the democratic experiment. While King held anti-capitalist beliefs since his childhood, his heart was strummed by the Watts riots and tuned during his time in Chicago in 1966.

By facing the full weight of the state police violence on the Edmund Pettis Bridge in Selma, Alabama, SNCC and SCLC staff and supporters set the stage for the passage of the historic Voting Rights Act of 1965. Black folks bent the arc of the universe toward justice. The United States had been true to what she said on paper. Having already passed the Civil Rights Act in 1964, the nation had honored voting protections of all citizens. Leaders in the movements and everyday black folks celebrated the momentous occasion. The national euphoria quickly dissipated. Their joy would soon become lamentations – confetti into ashes.

A few days after King and other SCLC staff witnessed President Johnson sign the Voting Rights Act, Watts exploded on a hot August night. An instance of police violence set the black community on fire. For six days, the Watts community burned and more than 30 people were killed and some 1,000 injured. There were 3,438 arrests, and over $40 million in property damage. At the time, Watts was one of the poorest black communities in the nation. The de facto segregation of Greater Los Angeles was alarming and the economic deprivation maddening. Moreover, Los Angeles’ militarized police force was notorious for its violence against black and brown people, regardless of gender. The riots, as King noted, were the “cry of the poor,” hopeless and suffering from high levels of unemployment. Acts of violence were weaponry that the black poor deployed to express rage against their oppression.

Understanding the riots as an international security issue, California Gov. Pat Brown appointed former CIA Director John McCone to head a commission investigating the Watts riot. The McCone Commission echoed King’s call for a multibillion-dollar investment in poor black communities. The report named inferior living conditions – poor schooling and high employment – as the culprit in the dramatic event. Increasing funding for public services – public transportation and housing, literacy programs, preschool, low-income housing, job training – would prevent riots.

Central to democracy is the fundamental belief that one belongs and one’s voice matters.

King came to Los Angeles to push his message of nonviolence. He encountered hostile youths who were critical of his class location and who wanted to use violence as an option against systemic oppression. At one community meeting, King, accompanied by Bayard Rustin, was booed. One young man stood up and forcefully stated: “We will not turn the other cheek.” King – a southern black Baptist Brahmin committed to nonviolence – did not have the same experience as poor blacks from the ghetto. Positioning the riots as the poor people’s cry for attention in the ghettos of the North, King chastised reporters and society: “We got to give them more attention … and give them a sense of belonging.” Central to democracy is the fundamental belief that one belongs and one’s voice matters. When these outlets are not available through economic justice, in King’s analysis, riots are inevitable. To ignore the need for belonging as a basic feature of democracy is to call down the unnecessary fire and brimstone of social unrest. Though the urban poverty that King saw in Los Angeles was different, it was no less degrading than poverty in the South. Subsequently, he had to adjust his political analysis and programmatic emphasis to accommodate the context.

The Watts riot and King’s lack of experience with the urban black poor prompted him to push SCLC campaigns northward. Though members of his largely southern staff opposed the move, King embarked upon a Northern pilgrimage into black poverty. Chicago was one of the largest urban spatial habitats for the black poor. Many black Chicagoans were former southerners who fled the apartheid South’s totalitarianism – only to find themselves living in Northern squalor in an even stranger land.

Democracy was within their reach, but out of their grasp. Chicago was an ideal site to work out a response to economic injustice inside democracy. “We are moving in Chicago right now at this time in order to gain our rightful place,” King claimed with a distinct Southern drawl. He continued to lay claim to the inalienable rights of black humanity. “We must not let anybody make us feel that we were born to live in poverty and deprivation,” King edified an assembly of the black poor in Chicago. As God’s children, it was justified to demand those rights – making it clear that they would live in dignity and honor. The Chicago campaign encountered two obstacles that were different, but not new – recalcitrant politicians and angry black poor youths. King cast his lot with the black poor – the palpating heart of a panting democracy.

“We are tired of being lynched physically in the Mississippi and we are tired of being lynched spiritually and psychologically in the Chicago.”

Renting an overpriced flat surrounded by abject poverty, King moved his wife and children to the West Side of Chicago. He made the connection between the situation of blacks in the north and the south. “We are tired of being lynched physically in the Mississippi and we are tired of being lynched spiritually and psychologically in the Chicago,” he told the several thousand gathered in a Chicago stadium. The experience of living in a dilapidated apartment in a major Northern city cemented King’s disdain for the right to vote without economic justice. In Chicago he lived with and worked among gang members – the hardened and hard-core poor. King met regularly with black gang members in his Chicago apartment. He provided them with training in nonviolence. He carried their message to the Riverside Church. A major reason for his opposition to the war grew out of the time spent in Northern ghettos:

“As I have walked among the desperate, rejected and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. I have tried to offer them my deepest compassion while maintaining my conviction that social change comes most meaningfully through non-violent action. But, they asked, what about Vietnam? … Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today, my own government.”

In addition to seeing the war in Vietnam as immoral, King saw the war as a direct threat to Johnson’s War on Poverty. Like “a demonic suction tube,” resources were being drained from the poor in the US to kill the poor of Vietnam. His experience in Northern ghettos and the quagmire in Vietnam needed a tactical response. Having refused to believe that the bank of justice was bankrupt, King issued a notice to the the republic – the Poor People’s Campaign. On behalf of the abused poor, the Poor People’s Campaign was a direct confrontation with the federal government over spending in Vietnam and the lack of economic redress in the United States.

It was no longer about gaining access and opportunity in a morally bankrupt system, but rather about a radical transformation of society.

A few weeks after the Riverside speech, King challenged the SCLC to pressure Congress to pass an Economic Bill of Rights – a $30 billion anti-poverty program that included a commitment to full employment, a guaranteed annual income and the construction of 500,000 low-income housing units. King’s stated goal with this feat was to move from an integrationist-reformist disposition to a revolutionary position. It was no longer about gaining access and opportunity in a morally bankrupt system, but rather about a radical transformation of society. A transformation was desperately needed to cool the embers flamed by social misery and police violence. King’s personal democratic socialist theology was, now, on full display. Divested of the need to secure white “moderate” support and abstaining from President Johnson’s political maneuvers, King sought to highlight the plight of the nation’s poor. On June 25, 1967, King preached at Victory Baptist Church in Los Angeles. “We aren’t merely struggling to integrate a lunch counter now,” he said. “We’re struggling to get some money to be able to buy a hamburger or a steak when we get to the counter,” King boomed from the pulpit. According to King’s theology, access to the right to vote was not enough to achieve black liberation inside the beloved community. July 1967 proved to be especially hot. Riotous rebellions took place in Newark and Detroit.

“Mass civil disobedience can use rage as a constructive and creative force.”

While fully acknowledging the realities that produce black rage, King was still committed to nonviolence. He proposed a mass act of resistance that would not only dramatize multi-racial suffering of the poor, but would also bring the city to a grinding halt until its legislative occupants addressed poverty. “To dislocate the functioning of a city without destroying it can be more effective than a riot because it can be longer-lasting, costly to society but not wantonly destructive,” King wrote. Civil disobedience would not contain black rage, but direct it at the source of black affliction – the federal government. “Mass civil disobedience can use rage as a constructive and creative force,” King pledged. Acknowledging that black people should be enraged, The Poor People’s Campaign would not “suppress rage but vent it constructively and use its energy peacefully but forcefully to cripple the operations of an oppressive society.” The Poor People’s Campaign would harness the rage of the poor into an act of mass civil disobedience by shutting the city down. This was dangerous political terrain. The civil rights movement, heretofore, depended upon federal intervention. The Poor People’s Campaign broke with that pattern and made the federal government the target. King and his staff met with Native American, poor whites’, and Chicano leaders to get endorsements and to mobilize their constituencies. The Poor People’s Campaign could have brought a great cloud of poor witnesses together who would have brought the city to halt.

King was slain standing in solidarity with poor black janitors in Memphis and the Poor People’s Campaign did not achieve its stated goals. And King’s prophetic warning concerning spiritual death has come to pass. In the past decade, the triplets of evil are embodied in correlating events: Hurricane Katrina (racism), the Iraq War (militarism), and the fiscal crash of 2008 (materialism). To make matters worse, Citizens United and the recent Supreme Court decision striking down limits to campaign contributions may be the last gasp of the American empire, signaling the trump of materialism over democracy. The onslaught of reproductive rights restrictions and anti-queer legislation combined with aggressive voter rights violations has taken the body politic off life support.

The United States may have a black president, but the black poor still do not belong.

The United States may have a black president, but the black poor still do not belong. In some urban centers, upwards of 50 percent of black and brown men are unemployed. It seems every other week there is a Trayvon Martin, CeCe McDonald, Renisha McBride or Jordan Davis – victims of state-sanctioned violence against black bodies. The UN recently issued a report condemning the United States for a racist prison industrial complex and racist policing (racism); illegal drone strikes, extrajudicial assassinations, indefinite detention, torture, and NSA surveillance (militarism) and criminalization of homeless (materialism). In the “Kids Count” Report, the Annie E. Casey Foundation indicated that African American, Latino, and Native American children lag in every early childhood indicator.

King warned the US of democracy’s pending doom here. King’s mission was to “redeem the soul of America.” The black freedom struggle, in part, accentuated redemptive possibilities – but the United States may prove beyond redemption. The triplets render the Statue of Liberty blind and mute. Like its greatest son, the body politic lays it head on its cooling board and the flag is its winding cloth. In the wake of King’s death, his beloved Coretta mourned: “He gave his life for the poor of the world, the garbage workers of Memphis and the peasants of Vietnam. The day that Negro people and others in bondage are truly free, on the day want is abolished, on the day wars are no more, on that day I know my husband will rest in a long-deserved peace.” To be sure, King is turning over in his grave.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.