When Stephanie Foxworth was imprisoned at Albion Correctional Facility, she spent long days lifting heavy sheets of metal, which were used to make garbage cans for New York City sidewalks, lockers for public schools like SUNY Buffalo State College and barbecue grills for state parks.

Her employer was Corcraft, also known as the New York State (NYS) Division of Correctional Industries — a state-run prison labor corporation that operates a range of enterprises in 13 prisons across New York State. Foxworth’s starting wage was 16 cents an hour. At that rate, it would take her three-and-a-half hours of work to buy a 55-cent postage stamp.

After nine months on the job, her pay had increased to 42 cents an hour. Now, upon release, she struggles through her days working as a McDonald’s security guard, enduring an aching back caused by her days of strenuous manual prison labor.

According to a representative for the NYS Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, incarcerated workers can earn 16 to 65 cents per hour at Corcraft, or up to $1.30 per hour in bonus pay for working dangerous and unsanitary jobs such as removing asbestos, mold and bird feces.

Foxworth said she never chose to work for Corcraft — rather, she was assigned to the job by the prison Program Committee. “I wanted out of Corcraft, period,” Foxworth said.

As students at the City University of New York (CUNY), we were shocked to find out that our institution purchases desks, chairs, shelves, and other items made by Corcraft’s incarcerated workers. This motivated us to interview nine formerly incarcerated people who, as confirmed by a Department of Corrections representative and agency records, worked for Corcraft at multiple prisons: Albion, Bedford Hills, Elmira, Great Meadow and Coxsackie Correctional Facilities.

Our research showed us that Corcraft is a gear in an enormous machine. It is a microcosm of the broader systems of dehumanization that treat people as expendable and exploitable for the private profiteers of the publicly funded prison-industrial complex.

“What would it mean to imagine a system in which punishment is not allowed to become the source of corporate profit?” UC Santa Cruz Professor Emeritus Angela Davis asks. “How can we imagine a society in which race and class are not primary determinants of punishment? Or one in which punishment itself is no longer the central concern in the making of justice?”

Orisanmi Burton, assistant professor of anthropology at American University, told Truthout that the primary purpose of prison labor programs like Corcraft is to save the state costs on prison operation and maintenance, so that the broader prison-industrial complex can continue to expand.

Corcraft’s number one customer is the Department of Corrections itself, as shown in documents obtained by the Legal Aid Society. The bed frames New York prisoners sleep on, the eyeglasses prisoners wear, and even the ankle restraint desks used to shackle 18-to-21-year-olds during “educational” programs at Rikers Island are all manufactured by Corcraft and then sold back to the Department of Corrections.

“Prison labor is essentially reproductive. It reproduces the prison,” Burton said.

Department of Corrections Directive #4803 states that every incarcerated person is assigned an available program when they enter a New York prison. Sometimes it’s education, drug treatment or counseling, but often, it’s work.

Today, about 870,000 incarcerated people, more than half the U.S. prison population, are working a job in prison, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS).

Correctional industry jobs like Corcraft, in which incarcerated people produce products to be sold to the state, are available in almost every U.S. state. But the majority of those incarcerated, the BJS reports, are working mundane facility maintenance jobs. This work can be mopping floors, scrubbing toilets, laundering uniforms and washing dirty trays in the mess hall. For these jobs, New York pays 10 to 33 cents per hour, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

Sarah DiLallo told us she was assigned to the Corcraft “NYS Clean” hand sanitizer factory inside Albion Correctional Facility when the pandemic hit. “None of us signed up for it. We were all forced to do it,” DiLallo said. “They said to you, ‘The only way you’re leaving this program is if it’s in handcuffs.’”

A Department of Corrections representative said that an incarcerated person’s interest is taken into consideration when being assigned a work program, and it is recommended (but not guaranteed) that the individual will have the option to leave an assigned work program after 90 days. If an incarcerated person refuses all program assignments, the representative said, they may be subject to disciplinary sanctions, including the loss of opportunities to have their sentence reduced or to get out of prison on parole supervision.

Foxworth said she requested to be taken out of Corcraft completely, but after 90 days, she was just assigned to a different facility within Corcraft — where as many as 7,500 garbage cans were spray painted each day. The chemicals in the paint affected her health, she said. “Every time I moved from the conveyor line and got anywhere near the paint, I got lightheaded.”

Foxworth said she asked her supervisor, who she referred to as Mr. Hyderman, to move her to a different station, but he ordered her stay at the paint booth. “And then maybe a month [later], I passed out in the booth,” she told Truthout.

Corcraft’s maximum wage of 65 cents per hour may be worth less than a pack of chewing gum, but it’s actually the highest paying job offered to people incarcerated in New York. And because wages for prison jobs are used to pay for necessities like sanitary items, calls to loved ones and additional warm clothing in the winter, Corcraft jobs are often in high demand.

Prison jobs also provide some reprieve from what formerly incarcerated University of Illinois scholar James Kilgore describes as the “purposelessness and excruciating boredom” of everyday prison life. This is why activists like Kilgore push for prison abolition and decarceration, rather than simple tweaks or reforms to the current prison labor system. “[Incarcerated people] need far more than higher wages or a union card,” Kilgore writes. “They need freedom.”

If You’re a New Yorker, You’ve Probably Used Corcraft Products

If you live in New York State, products made by Corcraft’s incarcerated workers are likely all around you.

The chair you sit in at a state courthouse, the desk you write on in a CUNY or SUNY classroom, and the speed limit sign you check on a New York street are all products most likely made by an incarcerated person, whose starting wage is about 94 times less than the state minimum wage.

Corcraft’s product line includes coffins to hold dead victims of COVID-19, crowd-control barricades sold to the New York City Police Department to contain Black Lives Matter protesters, and entire modular buildings that are converted into police stations and prisons. Even the customer service operators in some Department of Motor Vehicles call centers are incarcerated people working for Corcraft.

By law, Corcraft can only sell to state agencies. Its top customers include the Department of Transportation, Department of Sanitation, NYS Division of Homeland Security, the State University of New York and the Department of Corrections itself, as revealed in documents obtained by the Legal Aid Society.

Corcraft yielded $53 million in sales for the Department of Corrections in 2019, according to the New York City Comptroller.

The Department of Corrections reports that 1,820 of New York State’s incarcerated people are currently working for Corcraft, and another 5,000 are working a prison food service job. Those working in food service are paid a minimum wage of 16 cents per hour to prepare food, keep inventory and clean appliances in the prison mess hall, according to a department operations manual.

Three-fourths (75.2 percent) of these incarcerated workers identify as Black, Hispanic, Native American or another non-white race, according to a 2018 Department of Corrections and Community Supervision report. These numbers are reflective of broader racial disparities in the criminal legal system. In New York State, Black people are incarcerated at a rate of eight times that of white people.

Foxworth, who is Black, said the wages she received were dehumanizing — as were the ways in which her work supervisors spoke down to her and threatened her. “It was true slavery,” Foxworth said. “Slavery at its best.”

Health and Safety Issues

Every formerly incarcerated person interviewed for this article described a range of health and safety issues at Corcraft’s workplaces.

Stacy Burnett told us she worked as a clerk for the Inmate Grievance Resolution Committee while incarcerated at Albion Correctional Facility. According to Department of Corrections documents, this committee reviews complaints filed by incarcerated people from throughout the prison. Burnett said that many of those working for Corcraft feared retaliation for filing grievances, but those who did speak up often complained about the lack of proper protective equipment in the Corcraft welding facility at the time. “The gloves that they were issued went to their wrists, when they really needed gloves that went to their elbows,” Burnett said. “Their forearms would get burned when they brushed against the metal.”

Egypt Dior said she worked at the Corcraft print shop, where she on one occasion witnessed a man lose his thumb to a faulty hydraulic blade on a paper cutting machine. “It was sharp, sharp — like, scalpel sharp,” Dior said. When the incident happened, she said she heard a scream from across the room and saw the worker’s dismembered thumb laying in a pool of blood on the factory floor. Dior said this was an isolated incident at the print shop, but reflective of broader health and safety issues inside prison workplaces.

Maria Santiago told us she worked at the Corcraft call center for the Department of Motor Vehicles at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility. Santiago said she was denied medical leave and forced to work while undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer.

The Department of Corrections confirmed that Burnett, Dior and Santiago did work these positions while incarcerated, but did not confirm nor deny the occurrences of these events when asked, and said that they cannot comment on the medical histories of incarcerated people due to the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

Despite laws such as the Prison Litigation Reform Act that severely restrict incarcerated people’s ability to file lawsuits in federal court, there are at least 13 publicly available lawsuits filed against Corcraft by former incarcerated workers for alleged on-the-job injuries.

The alleged injuries include: a finger cut by an angle grinder; an arm caught in a disc grinder; a back damaged when a Corcraft construction worker fell from a scaffold; and a leg injured when an incarcerated worker was forced to continue working despite repeatedly insisting that he needed rest due to a preexisting leg condition.

“When these injuries happen, there’s no rush,” Foxworth said. “You cut your arm, and it takes 45 minutes for the facility to get you to the clinic.”

A Department of Corrections representative said that the department is required by law to follow workplace standards set by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) for all workers, including incarcerated workers.

However, attorney James Bogin of Prisoners’ Legal Services of New York said in an interview that the degree to which any agency outside of the Department of Corrections, OSHA or otherwise, has the power to enforce regulations inside state prisons is extremely limited.

Wages for Survival

For most incarcerated people, wages from prison jobs are not enough to get back on their feet when they get out. Instead of saving wages for post-incarceration life, people often need to use their earnings for necessities inside the prison.

The commissary is where they can purchase food, shampoo, toothpaste, floss, shaving cream, panty liners, reading glasses, Advil, aspirin, Pepto-Bismol, sweatshirts and nail clippers.

Even religious items are purchased from commissary. Metropolitan Correctional Center lists the cost of a “Muslim Prayer Rug” in prison as $12.96 — or 81 hours of work for a prison job paying 16 cents an hour.

New York prisons provide three meals per day, but Foxworth said those meals are hardly edible — let alone nutritious. “Sometimes you’ll eat the mashed potatoes if it’s really cooked and not watery. But being that they serve dinner at like 4:30, 5 o’clock, you’re gonna be hungry again” — necessitating food purchased from commissary.

Prisons provide incarcerated people with soap, made by Corcraft — but it’s so bad that prisoners often buy their own. “It just does not agree with our skin,” Foxworth said. “Your skin is always burning and itching. It washes clothes well though. You break it up into pieces and put it in hot water, your whites will be white. But as far as bathing with it, it’s horrible. So we buy soap.”

Some incarcerated people endure weeks without commissary though, so they can send the little money they make from jobs like Corcraft back to their families at home. An incarcerated worker making 16 cents an hour might make just $6.40 a week, which is barely lunch money for one of the 2.7 million children in the U.S. living with a parent behind bars.

Wages from prison jobs are also often needed, but insufficient, for paying off court fines. One in five families with an incarcerated loved one takes out loans to cover court fees, the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights reported. The average debt incurred for these costs is over $13,000 — which could have been a year at college for the three out of five formerly incarcerated people unable to afford school, the report details.

Low Wages and Sexual Exploitation

Many of the formerly incarcerated women interviewed for this article, including Stephanie Foxworth, Stacy Burnett and Ashlee L., said that the extremely low wages provided for prison jobs like Corcraft, combined with the financial burdens of court costs and commissary necessities, render many women in prison vulnerable to sexual coercion by prison guards.

“I’ve seen COs [correctional officers] come up to you and be like, ‘Oh, well, if you give me this, I’ll make sure your commissary’s full,’” Ashlee said. “They come in and they target the inmates that they know don’t have a lot. And then you have COs that people have walked in on, and they’re like, ‘You should keep quiet, because if you don’t, it’d be a shame that you go to lock.’”

Sexual assault against women in prison is prevalent throughout the country. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reported over 67,000 allegations of sexual assault in prisons between the years 2012 and 2015, for which data was most recently reported. Nearly half of those allegations were against prison staff.

Prison Work Reproduces the Prison

Jamie Northop, former director of marketing and sales for Corcraft, told Truthout that Corcraft relies upon paying prisoners less than $1.30 an hour in order to stay afloat. “If you suddenly made that $3, let alone $15, the ultimate cost to manufacture the product would become four times what you could charge in a fair market price,” Northrop said.

If all the people laboring in U.S. prisons were to be paid the current federal minimum wage of $7.25 instead of the average prison wage of 63 cents, the prison system’s operational costs would increase by 168 percent.

Northrop said that during his 1983-1994 tenure at Corcraft, the company grew by $40 million in annual revenue. He attributes this growth to an increase in contracts between Corcraft and over 114 private companies.

The aluminum processed by the Corcraft foundry, for example, is sourced from Rochester Aluminum Smelting Canada. It is then converted by incarcerated workers into fire hydrant caps, and sold to state agencies, including the New York City Department of Environmental Protection.

More than 4,000 private corporations in the U.S. today have a vested financial interest in the continued expansion of the public prison system, the organization Worth Rises reports. These corporations provide prison construction and design, food, health services, money transfers, data and information systems, security technology, phone call and email services, transportation, shipping, electronic ankle monitoring, bail bonds, and much more.

Some of the largest private entities that profit off of mass incarceration are the banks that loan money to states for the operation of public prison systems. New York State is $3.9 billion in debt for the operation of its prison facilities, the State Division of the Budget reports. This debt is owed to banks including Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Wells Fargo, Citibank and Morgan Stanley.

CUNY Graduate School Professor Ruth Wilson Gilmore argues that private profiteers are not drivers of mass incarceration, but rather, parasites off the larger system. In her 2007 book, Golden Gulag, Gilmore writes that mass incarceration emerged in the 1970s stagflation era of high unemployment, and continues to function as a warehouse for the “surplus labor” produced under capitalism. When striking workers can easily be replaced by a “reserve army” of unemployed people desperate for any job regardless of the pay, leveraging power to bargain for wages is suppressed. Prisons, Gilmore writes, lock away “excess” unemployed people — particularly Black unemployed people — who would otherwise be likely to politically organize. Simultaneously, mass incarceration demarcates 70 million people with criminal records that hinder their prospects in the job market, forcing them to take low-paying jobs, if they can find a job at all.

“Prisons are an attempt to solve crises in our political economy. They neutralize millions of people who would otherwise be laborers,” Dr. Burton said. “Our political system is organized in such a way that the massive liquidation of huge amounts of people is required for capitalism to function properly.”

Historical Origins of the Prison-Industrial Complex

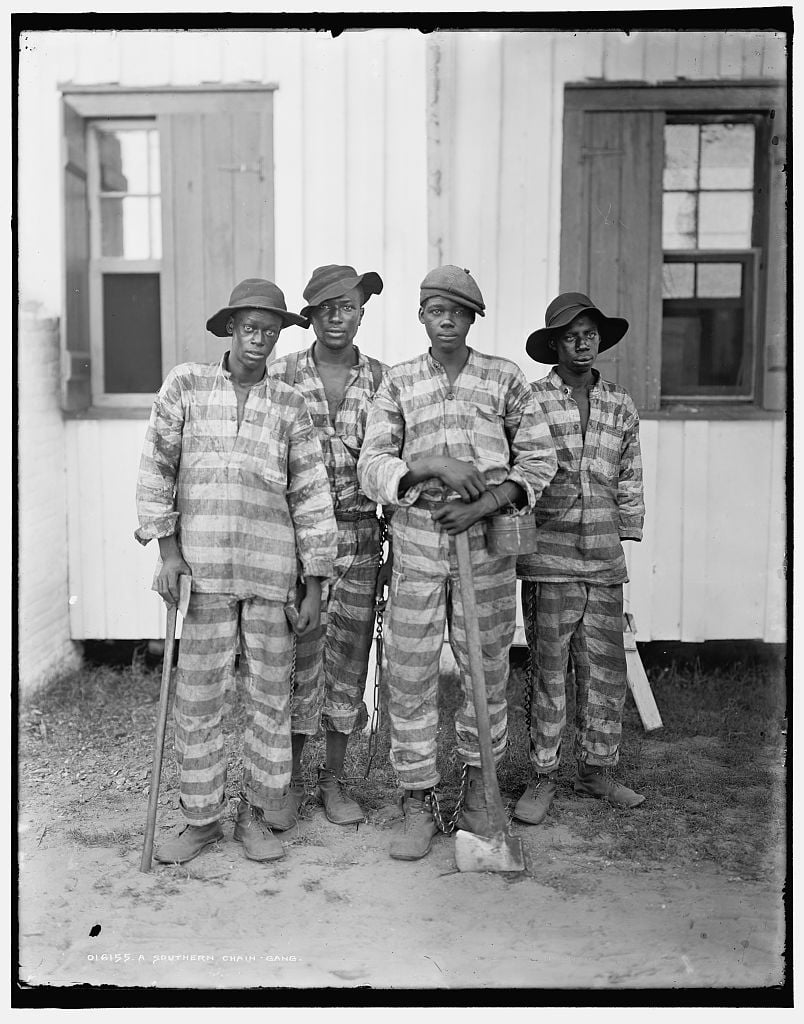

Some of the modern prison-industrial complex’s roots lie in the “convict leasing” system that extended throughout the country from the early 1800s to the 1940s, as detailed in books such as Slavery By Another Name by Douglas Blackmon.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Blackmon writes, tens of thousands of African Americans were arbitrarily arrested under laws known as the Black Codes, and forced into unpaid labor. The system was so brutal, the University of Houston reports, that it worked a quarter of all incarcerated Black people to death.

Convict leasing flourished in the South, but also accounted for $35 billion (in 2012 dollars) of the North’s industrial output, Queens College professor Joshua Freeman writes.

One of the first state prisons in the country to lease incarcerated people to private companies was New York’s Auburn Prison in 1821. The Cayuga Museum documents that convict leasing provided the capital for jump-starting many upstate New York corporations, including textile company the Auburn Tool Co., locomotive company McIntosh & Seymour and shoe manufacturer Dunn & McCarthy.

Convict leasing was a booming success for industrial capitalists, but a menace for some white laborers, who saw the system as a threat to their own job prospects and wages. The National Criminal Justice Reference Service writes that this opposition from labor organizers eventually led to the removal of convict leasing from the free market — but not its total abolition.

In 1893, New York established Correctional Industries, now known as Corcraft, at Auburn Prison, according to the Department of Corrections. From then on, New York would no longer compete on the free market with incarcerated labor. Rather, the Cayuga Museum details, labor derived from incarcerated people would be repurposed to the realm of “state use,” reducing expenses on state operations.

Other states and the federal government followed suit. In 1934, Federal Prison Industries, also known as UNICOR, was established. Today, UNICOR pays over 22,000 incarcerated workers a starting wage of 12 cents per hour to produce a variety of products for the state — half of which are sold to the U.S. Department of Defense.

Kevin Steele of the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC) told Truthout that he had the opportunity to request to work for Corcraft while incarcerated at Eastern Correctional Facility. Corcraft was the best-paying job offered at the facility, but Steele said that as a Black man, he is morally opposed to Corcraft’s historical origins and present-day existence.

“I don’t care how much money they’re paying me,” Steele said. “That was the highest form of slavery. And I’m gonna do whatever possible to rebel against the slave system.”

Worse Off After Prison

Correctional industry programs like Corcraft, Burton said, also exist to persuade the public that their tax dollars are going towards institutions of “rehabilitation.” In reality, the vast majority of U.S. incarcerated people are working unskilled maintenance jobs, and entering the job market upon release with significantly worse prospects than when they went into prison in the first place.

A Department of Corrections representative said that their agency does not track unemployment rates amongst its formerly incarcerated people, but that participants in Corcraft’s Optical Industries and Asbestos Services are frequently recruited by private firms for work upon release.

In 2018, the Department of Corrections reported 76 prisoners in its asbestos program and 63 in its optical program. This is a small percentage of the 67,000 people incarcerated in New York prisons and jails right now.

The people interviewed for this article who worked skill-based Corcraft jobs like welding said they left prison in a far worse position in life than when they entered.

When Foxworth left prison on March 17, 2000, she was flat broke, she said. “I didn’t have a dime saved up.” New York law guarantees people released from prison nothing more than $40 and a bus ticket to restart their life.

When released from prison, Foxworth said that she applied to jobs in metal fabrication, but none accepted her application. “I got the certificates, but they were totally useless. Everywhere I applied to jobs, they basically laughed at it.”

A Department of Corrections representative said that incarcerated workers receive a Certificate of Accomplishment for participating in Corcraft. The representative also said that incarcerated workers who do a separate Vocational Welding Program outside of Corcraft can receive certification through the NYS Department of Labor’s Apprenticeship Program and the National Center for Construction Education and Research’s Welding Program.

Regardless of her certifications, Foxworth said that the amount of employers willing to hire people with criminal records are extremely limited. So she ended up as a security guard at McDonald’s, where she must stand on her feet for eight hours at a time, triggering the lower back pain she said stems from her days of heavy lifting at Corcraft. “By the time I get on the fourth hour, my back is burning.”

Stories like Foxworth’s are highly common. The unemployment rate amongst formerly incarcerated Black women is 43.6 percent.

This lack of job prospects can lead to compounding problems. Formerly incarcerated people are 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than the general population.

COVID-19

Sarah DiLallo said she knows three women who tested positive for COVID-19 while working the night shift at the Corcraft Albion hand sanitizer factory. DiLallo was particularly close with one of those women, who she said received her diagnosis the day her family was driving four hours to visit her for her birthday.

In addition to hand sanitizer, incarcerated Corcraft employees have sewn over 371,000 masks for the state since the start of the pandemic, according to Mother Jones, and many of these people were not given proper masks themselves while doing this work.

Color of Change’s Megan French-Marcelin said in an interview that the dehumanization of incarcerated people allows for their exploitation in the prison-industrial complex.

“This labor is not only disposable, but actually not [considered] human,” Dr. French-Marcelin said. “We would never treat human beings this way. We would never put a person in a situation where they were literally sewing PPE — without PPE on their face — unless we did not think of them as human.”

Martin Garcia of the organization Worth Rises said in an interview that the dehumanization of incarcerated people is reflected in the state’s exploitation of their labor — as well as in the state’s lack of response to the pandemic in prisons. “They always fail to recognize that it’s people who are incarcerated,” Garcia said.

Nationally, over a third of a million incarcerated people have tested positive for COVID-19, as of March 3, 2021. Of those, over 76,391 people have not yet recovered and 2,446 have died.

One of those people was Waylon Young Bird, a 52-year-old Native American man with severe kidney disease who died of COVID-19 while incarcerated, despite writing 17 letters to his judge pleading for compassionate release.

Another was Marie Neba, a 56-year-old Black woman with stage IV breast cancer who died of COVID-19 while chained to a hospital bed at FMC Carswell correctional hospital, after being denied compassionate release.

“People in prisons and jails cannot socially distance, and often lack basic PPE,” said UCLA Law Professor Sharon Dolovich. “All public officials with the authority to release people from custody need to exercise that authority to the greatest possible extent.”

Organizers say the only real solution is decarceration — releasing people from jails and prisons — which campaigns including #CuomoLetThemGo and #FreeThemAll are calling for by pushing governors like Andrew Cuomo to grant mass clemency and pass legislation to release incarcerated people.

“I’m standing with my 10-year-old daughter who hasn’t seen her father since February,” said the Release Aging People in Prison Campaign’s Nawanna Tucker, whose husband has been behind bars for 30 years. “We don’t want our loved ones making masks, coffins, and hand sanitizer. We want them home with us.”

Special Thanks to: The formerly incarcerated people who used to work for Corcraft and took their time to interview for this article: Stephanie Foxworth, Egypt Dior, Stacy Burnett, Martin Garcia, Ashlee L., Maria Santiago, Veronica Taft, Judy Maloney, Genevive Shaw and Rona Love. The activists, organizers and scholars who took their time to interview for this article: Dr. Orisanmi Burton, Dr. Megan French-Marcelin, Sammie Werkheiser and Mothers on the Inside, Kevin Steele and the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC), Wayne Lane, Cameron Rowland, Maxwell Graham, Keri Blakinger, James Bogin (Prisoners’ Legal Services of New York, PLSNY). Project supervisor: Marshall Allen.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.