The traditional structure of power in the United States is typically seen as corrupt and inefficient. Many Americans feel isolated and distant from a system that provides representatives that a minority chooses.

Many Americans prefer a system that allows them to get involved. One way to get this is participatory budgeting (PB), first enacted in Porto Alegre, Brazil, by the Workers’ Party in 1989. This idea allows a community to vote on different projects, all chosen by residents, with an allocated budget typically given by government officials.

Today, the process is found in many places across the world, including the United States. Count Me In is a documentary that follows the first PB process in the city of Chicago. The film follows residents across different wards, including the 49th Ward that was the first to adopt PB.

I spoke with Ines Sommer, the director of the film, about what interested her in PB, Chicago’s processes and what lessons PB offers for the US. The following is our interview, which has been edited for clarity and length.

Brandon Jordan: What made you interested in making this film in the first place?

Ines Sommer: I live in Rogers Park in Chicago’s 49th ward, where participatory budgeting in the US started. So I’m just like Maria [Hadden, a resident in the film], I’m one of the neighbors who found a flyer on her front porch that said, “Help Alderman Joe Moore spend $1 million on neighborhood improvement projects.”

I went to one of the first PB assemblies and brought my family along. In Count Me In, there is a brief scene of a little boy raising his hand to say: “How about a stop light by the library?” That was my son! This “home movie” moment actually made it into Count Me In.

During that first year of PB in 2009-10, I made a short documentary that was then widely used by the aldermen and the PB folks to educate the public about the process.

When the announcement came a few years later that more Chicago aldermen were going to try out PB, I thought it would be really interesting to see how this spreads across the city, and how it would look different from my neighborhood because the other neighborhoods have different challenges.

A flyer held by a resident that promotes participatory budgeting in Chicago’s 22nd Ward. (Photo: Ines Sommer)

A flyer held by a resident that promotes participatory budgeting in Chicago’s 22nd Ward. (Photo: Ines Sommer)

What was the role of residents when it came to civic government and civic life before PB?

PB is an entirely voluntary process that elected officials need to give their okay to and hand over control to their discretionary money. I would say it was mostly the progressive aldermen who were already allowing input from their constituents that were interested in PB. The folks who were autocratic or have an “I know best for my community” attitude — they are not even interested in trying this out.

The gentleman in the garden story, Shannon Dudley — he’s the main instigator for the [community] garden [in the 5th Ward]. He had actually proposed a community garden six years prior to PB, collected signatures and got all kinds of neighbors on board. The aldermen just plain turned him down. PB was his opportunity to suggest it again, so his tenacity really paid off.

It was exciting to see residents use Tax Increment Financing (TIF) funds in Chicago, which are typically used for economic development. What are the effects of giving a community control over TIF funds?

I know other cities use TIF funds. From the little bit of history I’m aware of, they were initially thought of as a very progressive tool. For Chicago, it was under Mayor Harold Washington, who was much beloved by the community here, who first started this. Like any tool, you can use these development tools in a manner that turns them away from the original purpose.

I’m sure even PB could be used in a way that is not entirely positive. It really depends on who is using those tools and whether they have integrity. What happened in Chicago, rather than TIFs being exclusively used in blighted areas as intended, our entire city is now full of TIF districts. Our downtown financial district, which is certainly not blighted, is now in a TIF district. TIF budgets are now considered shadow budgets for our mayor, since there’s no oversight.

The TIF program is so controversial, because folks feel this is money that should fund our public school system that is in such financial crisis. Instead, it goes into all these developments and pet projects for the mayor. [Over] $50 million for a new stadium for DePaul University. All of these types of projects that community members feel they have no control over whatsoever.

Blocks Together, a community group in the 27th ward, which includes the Chicago/Central Park TIF, was able to pressure their alderman — who, as they say in the film, more often than not votes with the mayor. To allow them to use a PB process for parts of a TIF budget is a huge win. Either they don’t know about it, or they don’t understand what a radical notion it is to have community control over parts of a TIF budget.

Shannon Dudley successfully pitched a community garden in the 5th Ward’s participatory budgeting process. (Photo: Ines Sommer)

Shannon Dudley successfully pitched a community garden in the 5th Ward’s participatory budgeting process. (Photo: Ines Sommer)

I know there were some issues with the planning department after I finished making the film. I think the projects can go ahead, but there was some difficulty in financing because the rules are restrictive and hard for small nonprofits or companies to implement. But I know that Blocks Together is creating a toolkit and training for other groups on how you can do PB with a TIF. I think this will have a ripple effect.

One of the groups you follow is students in a classroom talking among themselves about ideas to improve their school using an allocated budget. Did the process create a new political identity for them? Were they aware of this change off camera?

This was actually not during the school day. These sessions were led by a youth organization called Mikva Challenge, which was founded by the late Abner Mikva, who was a federal judge and congressman. He was really interested in more democratic engagement for youth in particular. So Mikva Challenge is a fabulous organization that works in many after-school programs across the city and, in many cases, schools where you have underserved populations. The PB money that they were talking about was for the entire 49th ward. They were participating in the overall community PB process, not a separate process for youth only. There’s a PB story I didn’t shoot because it happened after video production was done: The principal of that school was so inspired that he set aside a small portion of his school improvement budget for students to use with PB methods. They worked on that for a year and the students came up with three ideas, including turning a corner of the cafeteria into a rec area. It’s a small thing and the budget was limited, but just the fact that students feel empowered to propose their own ideas, come up with full proposals, and then vote on them, was so encouraging.

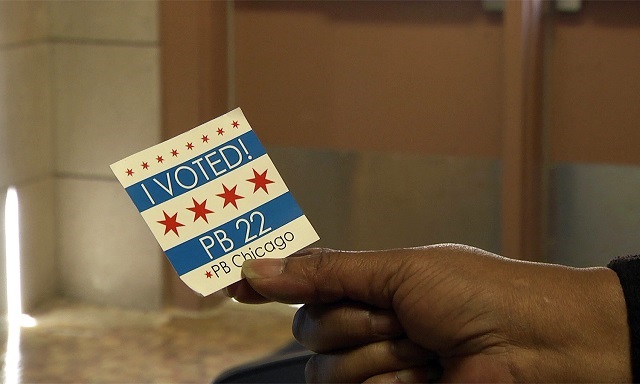

A sticker given to residents after they voted in the 22nd Ward’s participatory budgeting process. (Photo: Ines Sommer)

A sticker given to residents after they voted in the 22nd Ward’s participatory budgeting process. (Photo: Ines Sommer)

I found it humorous that a man at the 2014 Participatory Budgeting Conference in San Francisco said his mayor was more afraid of participatory budgeting than a minimum wage increase of $15 per hour. That’s quite surprising, considering the so-called radical idea of $15 per hour. Why do you think politicians are afraid of PB’s power?

I believe that speaker was from Florida. There are different issues in his city than in Chicago, but I think in very general terms, in order for PB to work, you have to be more collaborative in terms of wielding your power.

A lot of people are attracted to politics because it has a certain amount of power attached to it. For administrators, who are usually staff and not elected, getting all of this community input means more work. I think it’s a mixture of not wanting to give up power, being kind of comfortable with how things are run and seeing community input as more of a nuisance than something that’s integral to a planning process.

What are drawbacks involved with the PB? Gerrymandering is one problem that affects an effective PB process that the film highlights.

I don’t know how to compare that to other cities. That’s something I wasn’t even aware of before I made the film. In Chicago, our identity is very much shaped by neighborhoods we live in, but the borders of the wards or political districts we live in are much different and that’s where gerrymandering comes in. It is a hurdle for PB, because you’re kind of forcing people to work together across neighborhood borders, while half the neighborhood is left out because it’s outside of the ward borders.

PB is a process that really requires collaboration between community members and the aldermen’s staff. If you don’t get the collaboration from the staff, if they’re overworked or for any reason don’t want to put too much energy into it, then community members are forced to meddle through on their own without really knowing what the city agencies will actually allow.

Joann Williams is shown in the documentary knocking on her neighbors’ doors to promote a water play area project in the 22nd Ward’s first participatory budgeting process. (Photo: Ines Sommer)

Joann Williams is shown in the documentary knocking on her neighbors’ doors to promote a water play area project in the 22nd Ward’s first participatory budgeting process. (Photo: Ines Sommer)

The other extreme is if there’s too much hand holding by the staff. If they only allow for residents to color within the lines, then that really stifles creativity and true community involvement. If it’s really a collaborative process, you need involvement from both sides. I’d say community members are completely willing to do that.

Another hurdle is also the amount of money. People understand how much stuff costs and $1 million of a municipal budget is quite limited. People wonder why they should spend three or four months of regular meetings on allocating such a small pool of money.

So those are all absolutely challenges. I don’t want to paint too rosy of a picture of PB because these are serious challenges. At the same time, it’s incredibly empowering and positive to see. I think it helps people build community and they finally feel like they’re being heard.

The 2016 election ended with Donald Trump winning in an upset victory. Amid all the talk this year, there have been different takes on the health of democracy. Do you think participatory budgeting may help democratize democracy?

In general, in terms of creating more democratic decision-making, PB is a great start. It’s not just about the money; it’s about creating community dialogue and coming together to come up with solutions, rather than handing over power for four years to an elected official.

Another journalist asked me: “But isn’t this tyranny of the masses?” I thought that was quite telling that he was very fearful of what people might decide. That’s really counter to what my experience has been. People aren’t as self-serving as critics paint them. They aren’t just in it for themselves. I haven’t really seen that.

Initially, they might need their own street repaired, but when they start a PB process, they also talk about how to be inclusive and look out for the well-being of the entire ward. It’s not just handing over money and for self-serving individuals to run with it, it’s about looking out for the greater good of the community.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $47,000 in the next 8 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.