The popular fairytale of the US, present Trump reality aside, is that the country is a bastion of freedom unlike any other. History textbooks tout our freedom of speech, freedom of religion and freedom of expression as rights we uniquely hold. We like to imagine that in the US, one can engage in creative work at will — there are no Pussy Riots or Ai Weiweis here, no artists hounded by the political police and imprisoned for doing their art.

The reality, of course, is quite the opposite. From the blacklisting of Pete Seeger and the arrests of Lenny Bruce, to the radio banning of the Dixie Chicks — this country has a hearty tradition of artistic suppression. The FBI’s repressive attention to the late folk singer Dave Van Ronk — apparent in the singer’s FBI file –offers a new and disturbing window into this long US tradition of political suppression.

Making the FBI’s Security Index

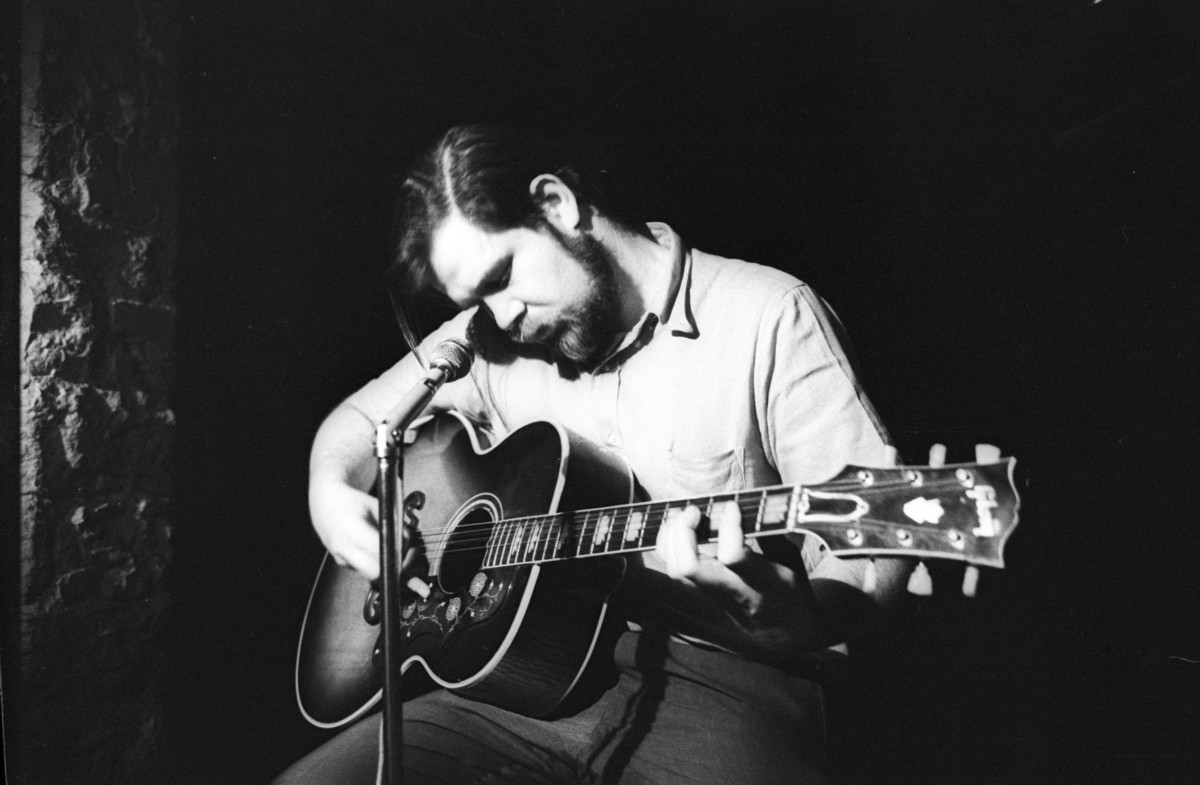

Dave Van Ronk’s life followed a winding path, from jazz aficionado, to banjo player, to staple of the folk scene. Along the way, he was a colleague and friend to artists, such as Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell and Tom Paxton — and served as mentor to an array of musicians that followed. Van Ronk might have slipped through the cracks of historical memory had it not been for his posthumous autobiography with Elijah Wald, The Mayor of MacDougal Street, and the subsequent film by the Coen Brothers, Inside Llewelyn Davis. Because of those works, however, he has assumed his rightful place as an important influencer during a pivotal cultural moment, the folk music resurgence of the late 1950s and early 1960s — the descendant of the left-wing folk wave brought by Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Lee Hays, Sis Cunningham and others nearly two decades earlier.

Van Ronk, while himself a highly political person, had as his professional focus traditional music rather than “protest songs” in the manner of Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs. This was mainly for aesthetic reasons; as he wrote, “It did not suit my style, and I never felt that I did it convincingly.” Perhaps this is why his memoir does not spend much time on the nuances of his political outlook, the internal struggles he was involved in, and the array of organizations with which he aligned.

By contrast the FBI, which opened a file on Van Ronk in 1963 — though their first report on him is in December 1957 — tracked his political life meticulously. As a result, we learn not only of his organizational associations, but the degree to which the Bureau had informants reporting on him. For example, the FBI received the following report on a Socialist Workers Party (SWP) branch meeting in St. Louis where one of the members describes an encounter with Van Ronk:

[He] said that he had been in recent contact with a singer who was making an appearance in St. Louis’ Gaslight Square. His last name was RONK or RUNK. He was a young man from New York City who obviously represented the minority voice of the SWP as he was rather critical of FARRELL DOBBS [a leader of that group]. He seemed to feel that the SWP should do more insofar as infiltration of union organizations. (St. Louis FBI, 8/6/63)

While the identity of the informant reporting on the meeting is unknown, what is clear is that the FBI had unique insights not only into the SWP, but also into Van Ronk’s travels and views.

Van Ronk’s tenure in the SWP would be relatively brief. As the file explains, he was part of a faction — called the [Tim] Wohlforth Group — that felt the SWP was not sufficiently radical and were expelled as a result. Those who left, including Van Ronk, went on to form the American Committee of the Fourth International, later to become the Workers League.

Though short-lived, Van Ronk’s membership in the SWP resulted in his addition to the Bureau’s Security Index. An FBI form dated April 16, 1963, recommended that Van Ronk, “Folk Singer and Guitar Player,” be added to the Bureau’s Security Index, a list requiring his detention in the event of a national emergency.

Because of his inclusion on the Index, the FBI would seek each of his home addresses for as long as he was included on the list. Thus, records show that between 1963 and 1964, the FBI called his answering service, talked to his building superintendent, and interviewed his neighbor — under “pretext” — to verify he was living at his then Waverly Street address. The snooping continued over the years, including after he moved to Sheridan Square, where they interviewed his new superintendent — again under pretext — to verify he lived there. It was not until 1972 that he was finally removed from the Index — and then only because it was being closed down.

The Lost Seaman’s Papers

In the film, Inside Llewelyn Davis, there is a plotline involving Davis’s attempt to renew his union card so he could work again as a seaman in the Merchant Marine (a civilian/governmental shipping entity that also supports the US Navy), only to discover his papers have been thrown out. That story was derived from Van Ronk’s own account in Mayor of McDougal Street where he describes his stint working in the Merchant Marine and how, after having his wallet containing his seaman’s papers stolen, he decided to cast his lot wholly into being a folksinger. According to Van Ronk, “It might take six months or a year before I could get a new set and ship out again…. Furthermore, with my politics and all my Commie friends, it had been a small miracle I was given them at all.”

As it turns out, Van Ronk’s misgivings were well founded. In conducting background research to determine whether or not to add him to the Security Index the FBI reviewed copies of his record albums. In doing so, they learned, according to a Bureau memo from February 15, 1963, “The cover of one of the albums reflects that subject in the past has been a merchant seaman”. Discovering this, they passed the information on to the Coast Guard’s Intelligence Division. The head of the division, in a letter dated July 11, 1963, wrote to FBI head J. Edgar Hoover, asking if he might supply witnesses who could testify to the “desirability of denying Subject a document through hearing procedure.” Hoover responded on July 22 by offering the services of the Special Agent who “observed the subject [Van Ronk] entering the SWP headquarters.” In the end, no hearing was held — Van Ronk had moved on. Regardless, it validates the suspicions. As Elijah Wald wrote in an email to Truthout, “Dave would have loved the evidence that he was not just being paranoid when he thought they would deny him a new seaman’s certificate.” In fact, the Bureau and Coast Guard were well on their way to doing just that.

Obtaining 4F Status

The Bureau’s file on Van Ronk is a chilling example of governmental intrusion. This can be seen in striking fashion in the FBI diligently tracking down the health report from Van Ronk’s military physical. In a report dated May 22, 1964, they record the following:

The conclusions of the examining physician “Eyes – Hyperopia. History of Asthma. Appears very tense and jittery. Has many phobias and anxieties. Tremors of extended hands (severe), moist, clammy, hands. Speech halting and occasional stammering. Inadequacy. Psychoneurosis severe”. Found unacceptable for military service for physical and mental (psychiatric) reasons.

The symptoms, as it turns out, were largely the result of a put on. As Terri Thal, Van Ronk’s ex- wife recalled in an email to Truthout:

Dave and a friend from Richmond Hill, Queens were going for the pre-induction physical at the same time, and in a successful attempt to get 4F classification, David rehearsed manifesting a psychiatric problem. Before they went, they smoked a lot of marijuana and Dave practiced shaking and stammering.

He did, however, have real health problems, specifically being plagued by asthma, which included trips to the emergency room.

For their part, the FBI appear to have taken — or chose to take — the induction report at face value. That might explain why in his subsequent Security Index reauthorization forms they repeatedly stipulate not approaching Van Ronk directly. As one such form, dated April 14, 1964, states:

Subject previously interviewed (dates) never

Subject was not reinterviewed (state reason) because of his emotional instability and his employment as a folk singer it is felt the interview of subject could possibly result in embarrassment to the Bureau.

In other words, they were concerned Van Ronk would sharply challenge the FBI and given his status as a public figure might expose what they were up to.

Politics and Art

Dave Van Ronk was an artist who by and large did not write or popularize “political music,” his view being that there could be a divide between art and politics. As he wrote, “Just because you are a cabinetmaker and a leftist, are you supposed to make left-wing cabinets?” This distinction, however, was not one the FBI made. While it was Van Ronk’s affiliation with various left-wing organizations that were the immediate catalyst for his file, the FBI made clear Van Ronk was a Trotskyist and a folksinger. Given the legacy of the Cold War, it was the latter, with its potential for reaching a mass audience that made him a more critical target.

Van Ronk’s career began a mere five years after the singing group, The Weavers, had been blacklisted from the wider national stage. Their sin was not in performing songs such as “Goodnight, Irene” and “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine,” but of their members having been affiliated with the Communist Party in the 1940s. For the Bureau and other elements of the ruling apparatus, to be associated with an organization that challenged the dominant capitalist paradigm — even if that association was in the past — was disqualifying of the freedoms that are supposed to be paramount. In the 1950s, artists such as Pete Seeger, Cisco Houston, Burl Ives, Josh White, Sis Cunningham and others were confronted with a career choice: either publicly denounce their previous affiliations with communists — which White and Ives did — or be kept from reaching a mass audience.

It is worth noting in that regard that Van Ronk was approached to be part of what would become the musical group Peter, Paul and Mary as it was forming. Had he joined — given the popularity of that group — it is not hard to imagine him being run out because of his politics. Of course, that was not the case; he instead labored at a lower level of recognition.

There is a level of nuance here. Van Ronk was not kept from having a career as a folk singer, much in the way that Pete Seeger was “allowed” to play colleges and smaller venues while having his national career torpedoed. The relative strength of the US economically and politically meant it did not need to resort to detention or more draconian suppression, though it nonetheless retained that option. Yet it was the case that Van Ronk — marked for detention, subject to constant surveillance and object of schemes to keep him from getting work — was impacted time and again. Terri Thal — herself a political activist — gives a further sense of this in an email to Truthout:

Over the years, the FBI queried our neighbors about us and we believed our phone was tapped because once, I picked the phone receiver up quickly after having been on a long phone call and heard my previous phone conversation. Later, after Dave and I separated, I worked for a brokerage firm for a short time. One day, we were told that all employees were to be fingerprinted the next day. I considered what to do … but I didn’t have to make a decision; I went to work the day we were to be fingerprinted and was fired that morning. Later in the week, the building’s superintendent told me that the FBI had asked him and others who lived in the building about me; my landlord told me that he had told the FBI agents that I was a very nice person.

Van Ronk and Thal knew they were under the eye of the FBI, and this operated as both a visible and invisible sword of Damocles. As Van Ronk’s decision to not try and regain his seaman’s papers attests, it conditioned how he went about living his life. What the overall impact was and what would have been different without such scrutiny is an unanswerable question, if nonetheless a highly relevant one.

It’s important not to write off the surveillance of Van Ronk as a moment from the “bad old days” or assume that artists today can say what they want without fear of retribution. While the means of suppression have changed, there are other forces playing a repressive role. Today, we see certain types of media, governmental agencies and organizations on the hard right enforcing unstated boundaries. As a result, artists such as the Dixie Chicks, whose front woman Natalie Maines publicly questioned the US war against Iraq, have their country music career shattered by the powerful Clear Channel corporation (now iHeart Media) banning them from their radio and spearheading a movement against them; or Joan Baez disinvited by the US Army to perform for recovering soldiers, decades after her anti-Vietnam war activism; or the rapper Common slammed on Fox News and disinvited from speaking at a university commencement for a song expressing sympathy for Assata Shakur. These and a multitude of other incidents — to say nothing of moves in operation yet hidden — underscore the tenuous nature of artistic and political freedom in the United States.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $31,000 in the next 48 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.