Nekima Levy-Pounds watched the scenes of officers slaying unarmed Black men replayed, one after another, in major cities across the United States, including New York, Charleston, Chicago, Milwaukee, Cleveland and Cincinnati. During all of them, she clung onto one hope: to never see the same stories unfold in Minneapolis, where she raises her 11-year-old son, heads the local NAACP and participates in the local Black Lives Matter movement.

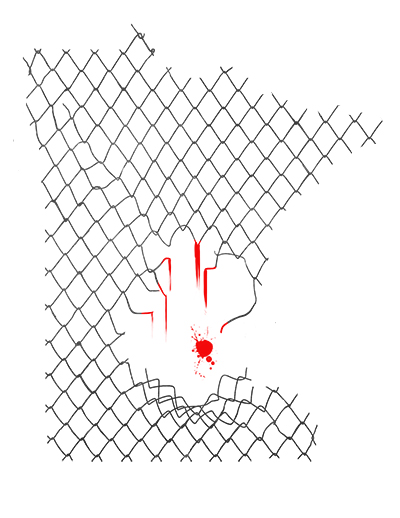

However, it’s clear that Minneapolis, too, is home to the kind of police violence that has inspired protests from Ferguson to Baltimore and led to the birth of Black Lives Matter, a national racial justice movement fighting against police brutality.

By November, Levy-Pounds found herself on her knees on a cold Minnesota night with her hands raised in the air and her eyes fixed on scores of state troopers on I-94, one of the state’s busiest highways.

“It’s not a surprise that the conduct of Minneapolis police officers has gotten so bad that someone would be shot in the head.”

She was among hundreds of Black Lives Matter protesters in solidarity with Jamar Clark, a 24-year-old unarmed Black man who died a day after police officers shot him outside his sister’s Minneapolis apartment on November 15.

The officers were responding to a call from paramedics, who reported that Clark was interfering with their work to help a victim in the apartment. Police say they struggled with Clark, who was unarmed, when they tried to arrest him – and an officer pulled the trigger, shooting Clark in the head.

Those who say they saw the shooting allege Clark was in handcuffs when he was shot, a claim the police department disputes. “It’s not a surprise that the conduct of Minneapolis police officers has gotten so bad that someone would be shot in the head,” Levy-Pounds said. “But it’s shocking that the type of abuse that the Black community has endured at the hands of the Minneapolis Police Department has been allowed to persist for so long.”

The involved officers were identified as Mark Ringgenberg and Dustin Schwarze, who are currently on paid administrative leave, according to officials.

Demanding Videotape

The disputed shooting has sparked Black Lives Matter protests that have called for the release of video footage of the incident. But authorities have said they will not release any tapes because of the ongoing federal investigation.

Leaders of the group vowed to continue demonstrating until their demands were met. For nearly three weeks after the shooting, they occupied the Fourth Precinct police station in north Minneapolis, just a few blocks from where Clark was shot.

On December 3, officers in riot gear forcibly removed protesters from the encampment at the station, where they had set up about two dozen tents and canopy shelters. Protesters also had built several campfires to keep warm in the frigid Minnesota weather.

“We noticed a heightened police presence. It reminded me of what I saw when I went to Ferguson last November.”

Over a six-week period, the demonstrators took their protests to the streets, Minneapolis City Hall, the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport and the Mall of America – the nation’s largest shopping center. All together, protests have resulted in nearly 80 arrests.

“We noticed a heightened police presence,” said Levy-Pounds of some of the protests. “Police were out front wearing riot gear, guarding the Fourth Precinct – and it reminded me of what I saw when I went to Ferguson last November.”

She mentioned similarities between experiences in Ferguson and Minneapolis: Police building standoffs between them and demonstrators, using tear gas, pepper spray and rubber-coated bullets.

“I believe that the show of military force was unnecessary, expensive, and it was an exaggerated response to citizens standing up for their rights. This is a free country,” Levy-Pounds said. “We have the right to peacefully assemble. We have the right to take a stand when our government violates the principles of human rights and human dignity.”

She added: “And that’s what we felt was happening when Jamar Clark was killed. Because his death symbolizes the escalation of police violence that has been happening in this community for decades.”

Police Killings of Black Men

The shooting of Clark adds to a long list of unarmed Black men who were shot and killed by white police officers, incidents that have sparked national debate and shed light on police violence in the United States.

Oftentimes, encounters that begin with a minor incident – such as traffic stops or disturbances – end with unarmed Black men shot dead.

It happened in Ferguson in 2014, when a white officer responding to a convenience store robbery shot and killed Michael Brown, the 18-year-old unarmed Black man.

It happened in Cincinnati, when 43-year-old Samuel DuBose was shot in the head in July 2015 after he was pulled over for driving without a tag.

“Minnesota has perfected the art of suppressing and subjugating people of color.”

A similar incident also replayed in Milwaukee, when an officer fatally shot Dontre Hamilton, 31, more than a dozen times. The officer was reportedly responding to a call from employees at a nearby Starbucks who reported that Hamilton was allegedly “disturbing the peace.”

Nothing is more painful for Levy-Pounds than the killing of 12-year-old old Tamir Rice, who was slain in Cleveland by officers who said they mistook his toy gun for a real weapon.

“My son is now 11 years old, only one year younger than Tamir Rice when he was shot and killed,” she said. “My son could easily be in that situation because of the heightened level of police violence that we have to endure.”

In 2015 alone, about 25 unarmed Black men have been gunned down by police officers across the United States, according to a Washington Post report. Of those, three were fatally shot in a two-week period in April.

Among them was Walter Scott, 50, who was shot and killed by a white officer in South Carolina. Scott’s murder was captured on a video that showed him running away and the officer shooting him in the back.

According to a Raw Story article, police have killed at least 1,152 people nationwide in 2015, with no evidence of violent crime involved in the incidents. Many of those killed have been unarmed Black men.

In 2015 alone, for example, 14 major police departments – St. Louis, Atlanta, Kansas City, Cleveland, Baltimore, Virginia Beach, Boston, Washington, DC, Minneapolis, Raleigh, Milwaukee, Detroit, Philadelphia and Charlotte-Mecklenberg – killed only Black people.

In Minneapolis, the killing of Clark is an example of longstanding injustices that Black communities in Minnesota have endured, said Adja Gildersleve, an organizer with Black Lives Matter Minneapolis.

“There is a lot of injustices, a lot of disparities in Minnesota,” she said recently at a community forum in Minneapolis. “It’s the worst place to live for Black folks and we have the largest disparities in the nation.”

White Supremacists Attack

As the Black Lives Matter group demonstrated outside a police station precinct in Minneapolis in November 2015, four men opened fire at the protesters, leaving five injured.

Leaders with the Black Lives Matter movement have characterized the shooting as a hate crime and have said the perpetrators were white supremacists, calling for federal terrorism charges against them.

Mike Freeman, a Minnesota county attorney, noted that the attacks were racially motivated. According to a criminal complaint, one of the shooters, Allen Lawrence Scarsella, made a video with a friend using derogatory remarks about Black people.

In the video, Scarsella said that they were on a “search and recovery mission” – and his friend displayed a handgun as he ended the recording with “stay white.”

“What happened last night was a planned hate crime and an act of terrorism against activists who have been occupying the Fourth Precinct,” said Misky Noor, Black Lives Matter Minneapolis spokeswoman, at a press conference a day after the shootings.

“Four masked men approached our encampment site outside of the Fourth Precinct and began filming, the same behaviors that have been exhibited by armed white supremacists who had previously visited the encampment and issued threats,” she added.

On November 30, Scarsella was charged with five counts of assault with dangerous weapons and one count of riot. His friends – Nathan Gustavsson, Daniel Macey and Joseph Backman – were charged with rioting as well.

Arrest Disparities Reveal Systemic Racism

As was reported in cities throughout the nation, law enforcement in Minneapolis has targeted Black communities and disproportionately arrested members – sometimes with no apparent reason, like in the case of Hamza Jeylani who was pulled over in early 2015 by a Minneapolis police officer.

The 17-year-old eyed Officer Rod Webber approaching the Toyota Camry he was riding in with two friends after playing basketball. So Jeylani hit the record button on his cell phone to capture the moment the officer threatened him and put him in handcuffs.

“Plain and simple, if you [expletive] with me, I’m going to break your legs before you get the chance to run,” the officer is heard saying in the video.

“I never said I was going to run,” Jeylani said in response.

“I’m just giving you a heads up. Just trying to be Officer Friendly right now,” the officer replied.

“Can you tell me why I’m being arrested?” Jeylani asked.

“Because I feel like arresting you,” the officer said.

According to a recent report by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Black residents in Minneapolis are nearly nine times as likely as white people to be arrested for low-level offenses such as traffic violations and theft.

The study underlines a wide disparity in the way officers treat Black people, especially those who live in the city’s north side, where Clark was gunned down.

“The sad reality is that the Minneapolis Police Department has been out of control for years,” Levy-Pounds said. “We’re demanding they stop the use of the excessive force and the over criminalization of African Americans in the City of Minneapolis.”

The Minneapolis report adds to the swelling statistics the ACLU has collected over the years from major cities nationwide that have suffered decades of police brutality.

“Reports from New York, Chicago, (both this year and last), Newark, Philadelphia, Boston, metropolitan Detroit, and Nebraska all describe police departments that reserve their most aggressive enforcement for people of color,” according to the study.

Anthony Newby, executive director of Neighborhoods Organizing for Change in Minneapolis, told researchers in the report that communities of color in Minneapolis have been wrestling with systemic injustices.

“We’ve become the new premiere example of how to systematically oppress people of color,” Newby noted. “It’s done through our legal system, and … Minnesota has perfected the art of suppressing and subjugating people of color.”

Despite the shootings by the white supremacists and the multiple arrests of Black Lives Matter protesters, efforts to combat police brutality and racial disparities have been the main focus for Levy-Pounds and other Black leaders in Minneapolis – and around the country.

More than 50 people were arrested the night Levy-Pounds stood with the Black Lives Matter protesters on the highway. As she knelt between demonstrators and the police – who assembled to break up the protest – Levy-Pounds told officers to arrest her first.

“I want justice for my people,” Levy-Pounds said in a video moments before she was arrested and taken to jail. “I’m tired of my people being killed on the streets like animals. I’m not afraid. There has been a lack of accountability within this criminal justice system. I’m sick and tired of this.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.