We live in a world hungry for good environmental news. But that’s no excuse for journalistic or scientific spin passing as an unvarnished victory for the environment, nor for exaggeration of the value of a narrowly focused environmental treaty as a model for a universal agreement.

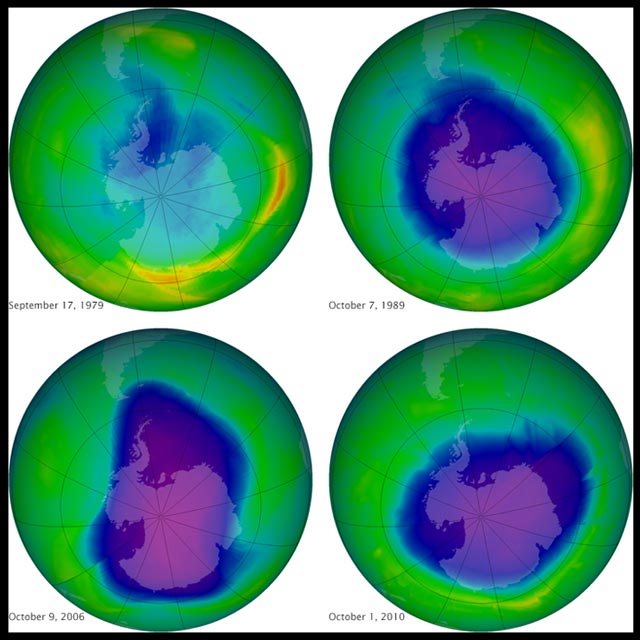

The “good news” arrived via the Associated Press on September 11: Thanks to the Montreal Protocol, atmospheric ozone is recovering. Scientists have been monitoring atmospheric ozone since 1989, the year the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete Ozone (a protocol to the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer) came into effect (it was negotiated in 1987). The scientists released their latest assessment on September 10, the subject of the Associated Press report.

Some background is in order. The Montreal Protocol is important on its own merits. A world of thinning atmospheric ozone is a world of increased skin cancer, eye problems and reduced agricultural yields and phytoplankton production. Every member state of the United Nations ratified the Protocol. But it is as a model for climate change negotiations and agreement that it takes on greater importance. The successful negotiation of the Montreal Protocol required agreement among policymakers, scientists and corporations, as will the replacement for the Kyoto Protocol.

The original Montreal Protocol achieved iconic status – Kofi Annan called it “perhaps the single most effective international agreement to date” – because it phased out production of five chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) known to destroy atmospheric ozone. CFCs were most widely used as refrigerants, solvents, blowing agents and fire extinguishers, as are their substitutes today. There have been five effectiveness-improving amendments to the original Protocol.

The Protocol and its amendments were possible for five reasons:

First, given the phase-in of the phase-out (zero production and use of the five CFCs was not required until 1996) DuPont, the dominant firm in the business, had time to research and manufacture the economical and less destructive substitute hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), and the nondestructive hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), even though it had to be pushed hard to do so. Lacking a chlorine atom, HFCs do not attack the ozone layer. HFCs and HCFCs are also less persistent in the atmosphere than CFCs, from two to 40 years for the former, to up to 150 years for the latter.

Second, CFCs were going off patent, so it was in DuPont’s interest to protect the multibillion-dollar market by developing HCFCs and HFCs.

Third, the science was clear on the Antarctic ozone hole, with but a handful of companies, led by DuPont, working to deny it.

Fourth, other ozone killers – several halons and some other CFCs – were not phased out until 2010.

Fifth, mandated phaseout of HCFCs does not begin until 2015, with zero production and consumption required by 2030.

The Montreal Protocol came to be because it posed a minor challenge to the profits of but a few firms, allowed time for new substitutes to come to market, and permitted use of less dangerous ozone-destroying chemicals, or those posing no threat at all.

Now back to the alleged good news report: According to NASA scientist Paul A. Newman, ozone levels climbed 4 percent in mid-northern latitudes at about 30 miles up from 2000 to 2013. (The tiny change for the better explains why it is hard to see much if any improvement between 1989 and 2010, or between 2006 and 2010, in the photos above.) The Associated Press does not tell us about ozone concentrations at other latitudes or other altitudes (except for 50 miles up, but no specific improvement figure is reported; this probably means the improvement was less than 4 percent elsewhere in the upper atmosphere).

The improvement is a “victory for diplomacy and for science, and for the fact that we were able to work together,” said Nobel Prize chemist Mario Molina, one of the scientists who first made the connection between certain chemicals and ozone depletion. Achim Steiner, executive director of the UN Environment Program, hailed the slight recovery of atmospheric ozone as “one of the great success stories of international collective action in addressing a global environmental change phenomenon.” Political scientist Paul Wapner said the latest findings were “good news in an often-dark landscape.”

The very slight thickening of the ozone layer is, as claimed, due to the phase-out of CFCs and other bad ozone actors. But it’s also due to the increased concentration of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere. Greenhouse gases cool the upper stratosphere. As that region of the heavens cools, ozone is rebuilt. The good ozone news is thus bad climate news.

Ready for more double-edged good news? The Obama administration appears intent on phasing out HFCs (just in time for the UN gathering and Peoples Climate March in NYC), and a chemical that is nondestructive to ozone, with only four times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide – the hydrofluoroolefin HFO-1234YF, also known as 2,3,3,3-Tetrafluoropropene – is ready to go as the latest substitute for CFCs.

The plan (as under the Montreal Protocol) is to give giant producers (including DuPont and Honeywell which own most of the patents) and massive users (including, Coca Cola, Pepsi Cola, Target and Kroger’s) time to phase in HFO-1234YF. The European Union directive that automotive air conditioners use refrigerants with global warming potential (GWPs) of 150 or lower had most European car makers begin shifting to HFO-1234YF in 2011 (a total ban on more powerful climate-changing chemicals comes in 2017). General Motors has been using HFO-1234YF in Chevys, Buicks, GMCs and Cadillacs since 2013. Chrysler reportedly plans to transition to HFO-1234YF as well.

Given the history of CFCs and their substitutes, at least some adverse effects from HFO-1234YF production and use, and some glitches in the transition are likely. German automakers worry that HFO-1234YF is both too expensive and too flammable (they’re investigating the use of carbon dioxide). In case of fire following a collision, HFO-1234YF releases highly corrosive and toxic hydrogen fluoride gas. One report had it that Daimler Benz engineers witnessed combustion in two-thirds of simulated head-on crashes. Considering the requirement that auto repair shops retool their air conditioning service equipment to use HFO-1234YF, it’s likely they’ll stick with the HFC R134a as long as possible. India is so far uninterested in moving toward replacing R134a by HFO-1234YF (China is working with the United States to jointly reduce emissions of HFCs). Canada, Mexico and the United States intend to propose amendments to the Montreal Protocol to command the phase-out of HFC production.

Pretending that miniscule improvement in atmospheric ozone levels is cause for celebration is not that big of a deal. The more serious problem is continuing to suggest that the Montreal Protocol is a model for international action on climate change. Dealing with CFCs and their problematic substitutes was, and is, infinitely easier than confronting climate chaos. Banning gases with especially high global warming potential (GWPs) is necessary, but nowhere near sufficient. Carbon emissions are the lifeblood of the global economy, of affluent life styles lived by the few but aspired to by the many. A vigorous climate convention requires far-reaching shifts in virtually every corner of daily life in the developed world.

Confronting ozone depletion permitted business as usual with but the smallest of tweaks that went unnoticed by most. Overcoming the ozone depletion denial industry was a trivial challenge compared to that posed by the forces arrayed to muddle climate science and stymie strong action.

Again: a climate change agreement that includes robust mitigation, a serious campaign to build resilience against a destabilized climate, and a foundation on the principle of climate justice requires genuine and widespread change.

Preventing catastrophic and irreversible climate change compels conversion of the complex systems of transportation, agriculture, generation of electricity, cooling and heating, waste management, manufacturing, technological innovation and more. It also requires transformation in developed countries’ sense of responsibility for past and future emissions. This is why we have yet to see one. Military budgets must be slashed and war machines stopped to free up the funds necessary for building clean green economies and to stop exacerbating the problem. How likely is that as the United States returns to Iraq for the third time in as many decades?

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.