Due process and equality before the law may be bedrock guarantees of the U.S. Constitution, but they often stop at the U.S. border. In recent years, countless immigrants have been uprooted from their communities, imprisoned and banished from their adopted country without ever getting a fair hearing before a judge — in large part because they were imprisoned and removed without ever seeing a lawyer.

Only about one in seven immigrants in detention have legal representation in court — usually the most vulnerable detainees with the fewest resources to fight their case. Unlike indigent defendants in criminal cases, who are entitled to a court-appointed attorney under the Constitution, there is no right to counsel in deportation proceedings. Unable to afford a private attorney, unrepresented immigrants often wend through an extremely complex litigation process without even understanding why they are being deported. They may also never learn about potential grounds for relief that they could claim, such as asylum, if they had a competent lawyer who could help them petition for a reprieve.

The need for immigration lawyers, particularly for people who are in detention, has exploded under the Trump administration, as more migrants are arrested and imprisoned, and the immigration court dockets buckle under a massive backlog of roughly 975,000 cases nationwide, mostly concentrated in New York, Texas, California and Florida.

But widespread outrage over Trump’s anti-immigrant crackdown has prompted some states and localities to step in to narrow the gap in legal representation by proactively supplying lawyers for detained immigrants in deportation proceedings. Some city and state governments have invested millions in local pro bono lawyer networks and “rapid response” legal aid teams for migrants threatened with removal. So far, though, only New York has pioneered a robust legal infrastructure for offering “universal representation” to all detainees who lack a lawyer and cannot afford one, according to the program’s income guidelines. But nationwide, communities are recognizing that a good lawyer is a migrant’s best hope for beating a hostile court system.

New York Leads Efforts in Deportation Defense

New York City launched the universal representation model with the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project (NYIFUP), an initiative of the legal think tank Vera Institute and local legal nonprofit organizations. Funded by city, state and philanthropic funds, the project has been working since late 2013 to assign lawyers for cases on the docket of Manhattan’s immigration court on Varick Street, and it has since expanded its services across New York City and Upstate New York. The model targets detainees who are within 200 percent of the poverty line, combining legal counsel with mental health and social supports. The clients, who include both legal permanent residents and undocumented individuals, had on average about 16 years of residence in the U.S. — people with deep family and community ties in the U.S.

Under NYIFUP’s “holistic legal services” model, lawyers do not simply represent their clients in court, but also support them and their families throughout the labyrinthine, often traumatic legal process, linking them to social workers and therapists if needed. The attorney helps demystify the legal proceedings while gathering evidence to build a client’s case for relief from deportation.

One former client of the SAFE Network, “Mariana,” recounted in an interview with Vera: “when you’re there and you don’t have a lawyer, it’s like, you feel somehow like, like, unprotected … because you don’t even understand what they’re telling you. You just hear them say all these court words and saying all these codes and stuff.”

Another former NYIFUP client, “Martin,” described in the program’s evaluation report how overwhelming it feels to appear before a judge and a government attorney:

If I wasn’t provided a lawyer, I couldn’t stand a chance. I didn’t know the law. Everybody in court needs a lawyer. To go in front of the court system without a lawyer, that’s like suicide, because the government counsel, they know the law…. They know how to fight it, so there’s no way I could win the case.

In its first two years, from 2014 to 2016, NYIFUP is estimated to have secured successful outcomes in 48 percent of cases — based on a statistical model for projecting case outcomes using federal immigration data — compared to just 4 percent of cases without representation. This constitutes an elevenfold increase in an immigrant’s chance of success. Overall, NYIFUP served some 840 parents of 1,859 children, most of whom were citizens. The project also boosted those families by helping several hundred people gain work authorization. Their legal victories collectively went on to generate an estimated $2.7 million in economic activity for New York City annually.

Advocates see publicly sponsored access to counsel as the bare minimum that the government can provide, as people are dragged through a painful, often chaotic legal gauntlet. Benita Jain, supervising attorney at the New York-based Immigrant Defense Project, told Truthout that for the people dragged into deportation proceedings, “Permanent banishment is such a heavy penalty that the least that this country can do … is provide a lawyer that can help them figure out” how to effectively plead their case. An upshot of the Trump administration’s deportation drive, Jain added, is the realization on the state level that “there needs to be a commensurate [public] investment in making sure that people’s rights are protected and that they have access to an advocate that can fight for them.”

Universal Representation Gains Momentum

The universal representation model is being replicated in many communities nationwide. The Vera Institute’s SAFE (Safety & Fairness for Everyone) Network, a coalition of state and local governments and legal organizations, has launched similar programs in 18 communities in 11 states, including California, Texas, Georgia and Minnesota, following the “merit-blind” template of NYIFUP, which accepts anyone who meets the basic criteria without regard to how “winnable” their cases are.

Various other legal aid initiatives have mushroomed in other regions: New Jersey recently allocated about $2 million for legal defense of detained immigrants through a consortium of nonprofits and law school clinics; and Chicago, Boston and San Francisco have expanded funding for immigrant legal defense in the wake of Trump’s intensifying Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids.

Although there had always been a push at the community level for funding for immigrant legal aid programming, advocates have observed that since the 2016 election, state and local politicians have been galvanized to invest more in grassroots immigrant defense. “The crisis of deportation is not unique to this administration,” said Rose Cahn, an attorney with the San Francisco-based Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC). Noting that Obama still holds the record for deportations during his tenure, Cahn told Truthout that Trump’s hyperaggressive deportation agenda has “provided in some ways an opportunity to finally get the policies passed” and secure a dedicated funding stream for legal counsel. California allotted $45 million for immigrant legal aid just after the 2016 election, much of which went to support the work of robust networks of legal nonprofits in the Los Angeles area and the San Francisco Bay area.

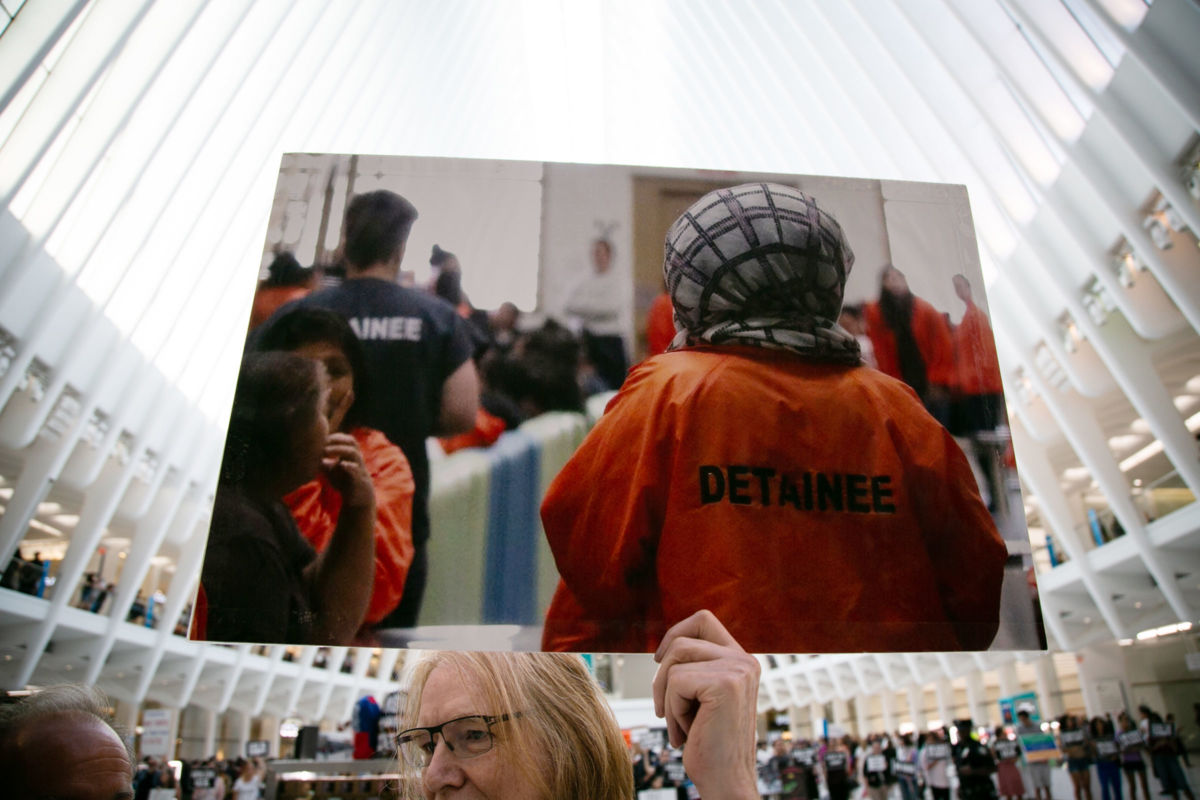

John Pollock, coordinator of the National Coalition for a Civil Right to Counsel, said that everyone facing deportation deserves the same right to legal representation that is afforded to indigent defendants in criminal courts — not least because the line between criminal and civil court proceedings are dangerously blurred for noncitizens. At a typical removal proceeding, Pollock said, “people who are detained come in in jumpsuits wearing leg irons and they’re facing a prosecutor, and everything about it looks criminal except for the fact that because the government has opted to call them civil … it’s really about what consequences they’re facing … not the label that someone’s put on them.”

Yet in many cases, just having a lawyer at your side is not enough, and some people are still excluded from “universal representation” programs. For example, some programs cover only immigrants who are currently detained, not those with removal orders who are not in federal custody. Others might fall outside of income guidelines. And for those who are ineligible for free legal counsel, their only option for representation might be hiring a private attorney, and with that, the risk of getting stuck with a fraudster or saddled with usurious fees. A client’s case can also be undermined by the arbitrariness and opacity of the courts themselves. The percentage of asylum cases in which relief is granted, for example, varies hugely, depending on the judge and jurisdiction. And many simply struggle with language barriers or fear interacting with any state institution, including police and the courts.

Congress has floated several bills to provide free counsel for immigrants facing deportation. A proposal to protect undocumented youth in the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals scheme included a provision for the appointment of counsel. Another standalone bill recently introduced in the House and Senate would provide lawyers to children and “vulnerable aliens,” including victims of torture and people with disabilities.

Some cities are bolstering their legal aid with community education campaigns, including Know Your Rights trainings, to help undocumented immigrants avoid court altogether and protect themselves from an ICE arrest. The Chicago Legal Protection Fund offers designated “community navigators” — peer advocates who support and guide migrants as they navigate the courts, public benefits system and other institutions. Such organizing efforts complement the state’s recently launched “Access to Justice Program,” which will support nonprofits statewide in providing legal aid for deportation defense in tandem with other social supports.

Laura Mendoza, a DACA recipient and immigration organizer with The Resurrection Project, one of the groups partnering with the Chicago Legal Protection Fund, said that in addition to direct legal services, the group emphasizes community outreach. The aim is to help communities protect themselves in an ICE encounter and hopefully avoid court altogether. “We want to make sure that people are informed about what’s happening, what they can do, how they can be proactive about everything that’s going on,” Mendoza said.

Though programs like NYIFUP have set a new standard for legal aid for immigrants, advocates acknowledge that the optimal remedy for the legal crisis facing so many migrants today is simply to change the harsh, onerous laws that keep them from attaining legal status. Universal representation, in Jain’s view, “doesn’t fully blunt the impact of unfair and unjust immigration laws or policy…. But an attorney can ensure that each person can make their strongest case.” Legal representation doesn’t always prevent deportation, but it does give immigrants a “fighting chance” in court.

Yet even those odds may be thinning, as the administration moves to further narrow avenues for due process in immigration courts. Trump recently moved to expand the scope of a legal mechanism known as expedited removal, from migrants apprehended recently near the border, to potentially any migrant living in the interior, with the apparent aim of enabling “fast track” deportation with virtually no meaningful judicial oversight. The administration is also pushing judges to speed up their processing of claims to cut down the backlog, and recently moved to strip judges of their autonomy by decertifying the immigration judges’ union.

Cahn of the ILRC told Truthout that legal groups around California are still grappling with resource constraints, which may force groups to limit their caseload, and often, “everyone feels maxed out.” Simply physically visiting clients who are locked up in remote detention centers is a challenge, Cahn said, and lawyers wrestle with the “pervasive problem … of how we get representation to people who are in detention facilities, when access to counsel is so limited, when there’s so many hurdles to people getting into the detention facilities and interviewing clients.” Despite California’s funding infusion, “there’s an implicit recognition that there may be people who are falling through the cracks, who aren’t getting the services that they need to remain in this country.”

Court logistics are also frustrating NYIFUP advocates in New York. As more hearings are being conducted via videoconferencing, forcing immigrants to speak to lawyers and the judge through a camera. Zoe Levine, a lawyer with the Bronx Defenders, says that compelling clients to testify from heavily guarded detention centers undermines due process, especially for clients with cognitive limitations or complicated asylum cases. While such technology is supposed to facilitate proceedings, Levine added, “if anything, it’s harmed the ability of us to represent our clients, and for our clients to get a fair day in court.”

Currently, advocates are pushing for further expansion of the universal representation model to cover immigrants who are not in detention, including the estimated 19,000 immigrants statewide who are non-detained and lack representation. But the goal of universal access to counsel might still get ensnared in local politics, reflecting the gradations of public sympathy toward different subgroups of migrants.

In New York City, the City Council and Mayor Bill de Blasio have clashed over whether NYIFUP should be allowed to use public aid to represent immigrants convicted of serious crimes. Private donors ultimately had to step in to fill the so-called “criminal carve-out” in NYIFUP’s budget. Moreover, it’s perhaps no coincidence that the proposals for legal defense programs tend to prioritize migrant children and abuse victims, who might be perceived as more sympathetic than, for example, people with past criminal convictions. Shiu-Ming Cheer, senior staff attorney at the National Immigration Law Center, said that politicians who are reluctant to seem too “soft” on immigration “don’t necessarily want to allocate money for something that might be perceived as unpopular.”

Popular or not, legal representation might be the only way to move toward justice in a dysfunctional court system. Absent a radical rewriting of immigration law, activist lawyers can only work to decriminalize immigrant communities one case at a time, chipping away at legal barriers in the courtroom, even as Washington keeps building new walls.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.