Click here to listen to this article.

Disability, carceral violence and problematic forms of racialization constitute a profound and hegemonic labyrinth, Talila A. Lewis argues. So what are the intersections between disability, criminalization, institutionalization and incarceration? How do these sites function as overlapping and inextricable forms of mutually compounded violence? And how do we go beyond theorizing how these phenomena are linked, but work to ensure that such braided structures are undone, deconstructed, abolished? In this interview with Truthout, Lewis discusses carceral dis/ableism, the danger of reformism and paths toward liberation for all. (This piece should be read in conjunction with our previous conversation about how ableism enables all forms of inequity.)

As an abolitionist and movement strategist, Lewis is committed to radical change and creating just and liberatory imaginaries. Lewis co-founded and served as the volunteer director of the cross-disability abolitionist organization HEARD for a decade, during which time they created the only national database of deaf/blind imprisoned people in the united states, advocated with and for incarcerated disabled people nationwide, and worked to correct and prevent wrongful convictions of disabled people. Lewis, who served as a visiting professor at Rochester Institute of Technology and as a public interest law lecturer at Northeastern University School of Law, also serves as an “expert” on cases involving multiply-marginalized disabled people.

George Yancy: Your important work considers the implications of what it means to be incarcerated and to suffer under ableism while incarcerated. This is not something I have considered before. There is a huge lacuna in my scholarship within this area and within my political praxis. The link between incarceration and experiencing disability raises the need for critical thinking through the theoretical lens of intersectionality. It is one thing to be part of an oppressive carceral system and yet another to be within that system as disabled. I would assume that, again, there is a process of amplification and an increase in precarity. Then again, perhaps to be incarcerated is already to be subjected to forms of medical and psychiatric discourse that are undergirded by ableism. What are your thoughts about the intersectional dynamics that I’m raising here and the discursive and ableist violence that seems to be embedded within prison life itself (or “prison death”)?

Talila Lewis: Disabled people have always been among the chief intended targets of all forms of incarceration, representing the largest marginalized population in jails and prisons (and almost one hundred percent of those confined in other locked institutions). Disabled people are disproportionately represented in jail/prison for two main reasons. First, the criminal legal system targets and disadvantages disabled people at every phase of the criminal legal process, and second because carceral institutions are disabling by design (so those who enter jail, prison and other locked institutions without disabilities almost assuredly acquire disabilities while incarcerated).

Disabled people are more likely to have catastrophic encounters with policing systems, with at least half of the people killed by law enforcement having disabilities, and disabled people quite literally being targeted for policing, incarceration and institutionalization. A recent example is New York City Mayor Eric Adams’s racist-classist-ableist “plan” to abduct and involuntarily hospitalize New Yorkers whom NYPD, firefighters/EMS deem disabled — most of whom would undoubtedly be Black, Latine, otherwise negatively racialized, and low-/no-income people who are unhoused. Euphemistically framed as “aid,” this is incarceration and eugenics through and through.

Disabled people are also disproportionately arrested, convicted and incarcerated (often despite actual innocence), and spend disproportionately longer time incarcerated than nondisabled people. Disabled people also are more likely to experience the worst these institutions have to offer due to dis/ableism. It is also more difficult to free disabled people from incarceration regardless of innocence, owing to carceral dis/ableism. Reentry and post-carceral surveillance and control agencies (i.e., parole, probation, e-carceration) are also dis/ableist and inaccessible and/or known to be insurmountable for disabled people. In short, disabled people are arrested and incarcerated more often, held longer, suffer more and return more frequently and faster than nondisabled people. Disabled people with other marginalized identities fare even worse.

To be clear, carceral institutions are designed to cause illness, disability, dis-ease, perpetual fear, and premature death. Outside the near constant toxic exposures and death-hastening deprivations, theft of freedom, all on its own, is disabling. Incarcerated disabled people go on living in these violent hyper-ableist institutions — living as the marginalized among the hyper-marginalized. While incarcerated, disabled people are punished mercilessly for having disabilities, targeted for extreme violence and exploitation, exposed to extreme neglect, denied access to accommodations, forced to fight for disability access and basic human decency (then punished for these righteous struggles). If they survive incarceration and are freed, they return to the free world with disabilities and immense trauma. But this comes as no surprise to those who understand jails, prisons, civil commitment, and modern psychiatric carceral institutions as progeny of plantations, asylums, poor houses, circuses and zoos, and other places to which dispossessed people have been subjected to savagery and barbarism of the “civilest” kind.

Poverty, “criminality,” and Blackness/Indigeneity — like disability — have long since been framed as heritable character flaws, moral failings and sicknesses that need to be cured and purged. Structural violence is never implicated, despite the very obvious economic, social, cultural, political, medical, educational, legal, and other generational deprivation, dispossession, and depression borne by those subjected to and dying from this nation’s violence. Azza Altiraifi reminds us that “work therapy” was honed during and after chattel slavery — and continues to today — employing medical authority and ableism to justify enslavement and other forms of confinement, to compel uncompensated labor and deny actual care while developing and assigning medical diagnosis, among other things. The links between penal, medical and economic incarceration are striking.

There are undeniable similarities, connections and overlays between Black Codes, Indian Removal and Appropriations Acts, Jim Crow, manumission, Public Charge Laws; unsightly beggar ordinances, anti-tramping, anti-solicitation and anti-vagrancy laws; and convict leasing, vendue, sharecropping, peonage, sheltered workshop and modern prison labor systems. The interchangeable and often indistinguishable sites where those targeted by these laws and systems inevitably find themselves — often cyclically — reveals the ease with which powerholders leverage ableism to categorize and (re)distribute marginalized people into and across carceral institutions on the basis of purported health, criminality and vulnerability. Some of these places include: plantations, stockades, privately owned and operated “homes,” and “houses of corrections” (i.e., jails/prisons); poor houses, workhouses, poor farms and homeless “shelters”; asylums, county infirmaries and prison hospitals; reservations, boarding and residential “schools,” orphanages and boot camps, among others. While the stated purposes of these institutions and practices always includes a positive spin (e.g., aid, treatment, cure, rehabilitation, correction, discipline, vocational skills development and proving, etc.), all are carceral regardless of their euphemistic name or stated benevolent rationale or claim. This is the backdrop against which we must understand and challenge eugenics like that proposed by Mayor Adams and other government officials nationwide.

Conditions at all of these institutions are horrifically similar and people confined in all of these institutions were at one time or another called “inmate,” even where they are now euphemistically called patient, resident, worker or client. Some of the obvious similarities include separating people from their loved ones; harsh indoctrination and “breaking” a person into assimilation; violence being used to coerce people to push their bodymind beyond its limits; and unpaid or underpaid dangerous disability-inducing labor being framed as character- and morality-building. People who refuse to quietly accept the injustices of these institutions are often deemed “maladjusted,” “intransigent” or “noncompliant,” and force-medicated, restrained, isolated and punished. People who fled these places were deemed fugitives and deserters and were severely punished, even killed to remind those who were still incarcerated in these institutions to “stay in their place” or else. The geographies, logics and conditions of these places, and the similarities between those confined within these purging places, make clear that the aim has always been to maintain control over populations deemed valueless, surplus or ungovernable to expand and protect white settler-colonial power and capital. No need to repurpose a facility or institution if it is already perfectly purposefully aligned.

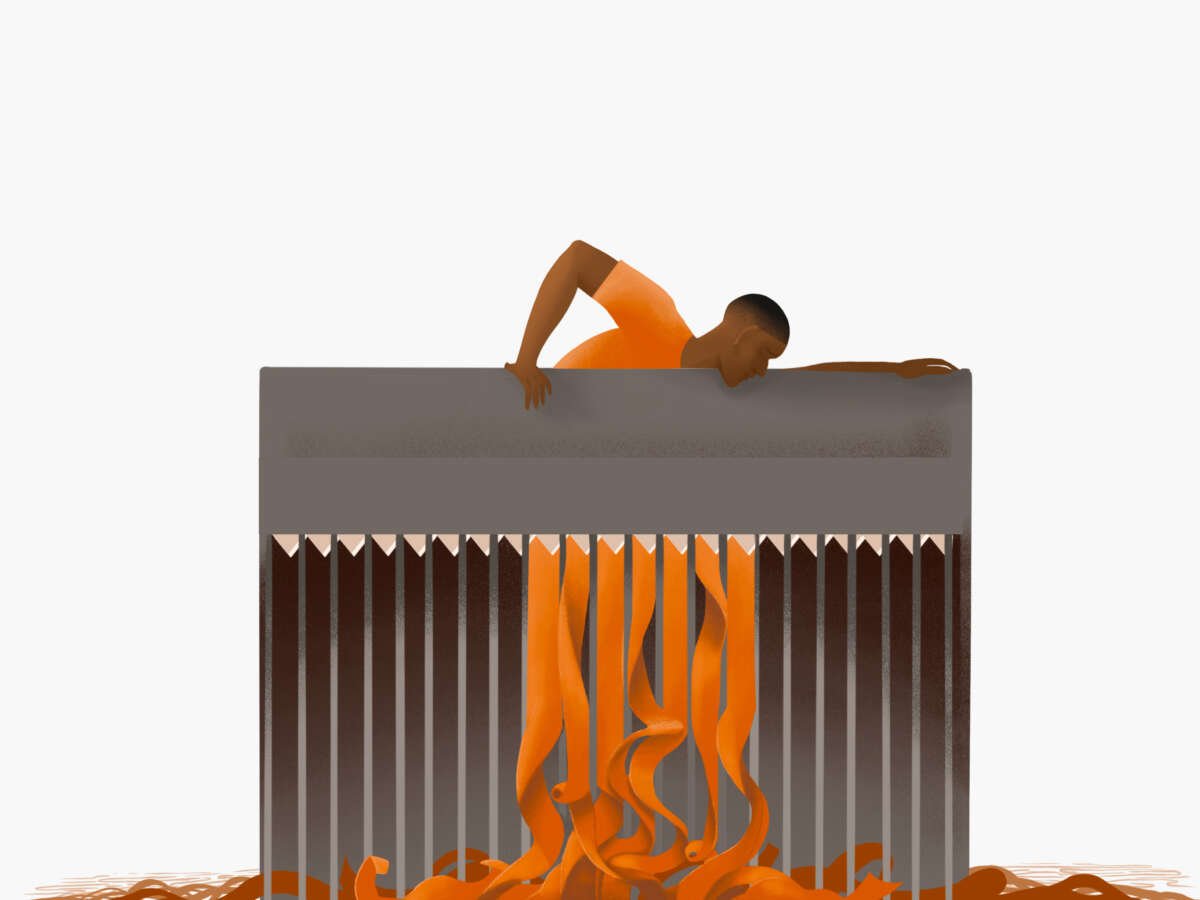

I understand incarceration expansively; and incarceration is eugenics. These are highly effective segregation, reproduction-preventing, deprivationist, disabling, profit extracting, killing machines. Reform-proof proven. Controlled by the state and corporations, they swallow up generationally dispossessed, patho-criminalized, multiply-marginalized and traumatized people using medical, legal and state authority. Incarcerators swear they are doing incarcerated people and society a favor. They engage academic, medical and scientific “professionals” to aid in “studies” that might prove their foregone conclusions. Incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people and their loved ones and communities sink further into economic depression, social degradation and political disadvantage for generations as a direct result of policing, pathologization and incarceration. Incarceration does not heal, make us safer, or positively transform individuals, harm, or our society. Quite the contrary. Incarceration destroys humans, families, communities, generations and society. Incarceration makes actual accountability and repair for harm more difficult to achieve, and it perpetuates violence and yet more harm. We must create the conditions that bring forth a world where incarceration has no place.

I have written more about how dis/ableism, racism, classism, and other oppressions intersect to create and shape how all marginalized people are made vulnerable to medical-carceral surveillance, criminalization, pathologization and incarceration here and here.

Please share a few challenges that most of us will not be aware of when it comes to seeking justice with and for disabled people who are part of what might be called a carceral continuum.

People might be surprised to learn that the application of modern civil rights strictures and strategies to matters concerning unfreedom under colonialism, racial capitalism and white supremacy often exacerbates the very normal and regular inhumanity of the unfreedom in question (e.g., incarceration/institutionalization). Oftentimes, leveraging civil rights principles and strategies actually increases the power of the system and broadens the scope and diversity of those who can be controlled and held in various states of unfreedom, and/or lengthening the time of the unfreedom.

One of the first civil rights laws — passed during Reconstruction — was written to, at least on paper, declare that Black people could access public spaces related to leisure, comfort, safety and connection: “people of every race and color, regardless of any previous condition of servitude … shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyance on land or water [i.e., public transit], theaters, and other places of public amusement…”

Of course, there were caveats. It was rarely enforced and the Supreme Court overturned the law just a few short years later. But, at least in theory, here we see civil rights declaring Black people to be deserving of access to positive benefits of living freely in a society they had been so segregated and ostracized from — and demonized and patho-criminalized by — that even upon gaining legal “freedom” they were still not safe or free (especially if their freedom involved pleasure, independence, thriving, connection with loved ones, being care-less, refusing to work and other reasonable humanities).

Much can and should be said about the counter-revolutionary impact of civil rights and the use of civil rights to reframe oppressed people as capable “workers” ready to be “integrated into the workforce,” especially during wartime (see, e.g., Executive Order 8802 during WWII). While these topics are well beyond the scope of this interview, I feel compelled to at least name that as currently wielded, modern civil rights often operate as a blunted and unreliable tool that may bring about some temporary incremental “advancement.” This, while serving as an incredibly effective and beguiling deradicalizing instrument of the colonial “civilizing project.” For example, civil rights erases the fact that reasonable demands like Land Back; wealth redistribution; guaranteed income, housing and health care; social interdependence and welfare; investment in marginalized communities’ solutions to the oppression they experience; abolition of all systems of violence, deprivation and unfreedom are very obvious and quite uncomplicated solutions to some of this nation’s allegedly “intractable problems.” The civil legal system is offered as an alternative to immediate provision or rightful revolution and ties oppressed people up in years, decades, and often generations of senseless and needless legal tiffs. Civil rights attorneys/advocates are heralded for their “fights” while oppressed communities are pushed further and further into dispossession and despair, notwithstanding civil rights “wins.”

Put differently, if civil rights existed during the time of enslavement and were being applied how we apply civil rights to incarceration today, abolition likely never would have come to fruition. Instead, we would have gotten more plantations — with a more “diverse” ownership, management and workforce; toothless settlement agreements between the government and enslavers; “independent monitors” to survey plantation conditions; entities paid to provide technical assistance, and training on enslaving; and policies about reasonable accommodations for qualified enslaved people with disabilities to be able to “participate” in plantation programs, services and activities. If this sounds absurd, consider that this is how most civil rights proponents think about and attempt to deal with the blight that is incarceration — especially those who call themselves moderate or neo/liberal. As it turns out, civil rights uncritically applied to violent ableist-white-supremacist-capitalist-cisheteropatriarchal institutions sever us from our hearts and humanity, which, of course, is where our freedom dreams and radical inclinations toward justice are held.

In the united states carceral context, we absolutely must consider the counterrevolutionary impact of civil rights and current civil rights tactics and strategies which are often at odds with, diametrically opposed to, and impeding true liberation. When considering injustice, perhaps instead of asking what the law, regulations and courts allow or interpret, we might ask ourselves other important questions like: “What would I demand if [the law, capitalism, white supremacy, ableism, etc.] had not captured and confined my imagination, creativity, dreams and heart?”

My work engages the theme of whiteness as a site of normativity. Much of my anti-white supremacist discourse is a challenge to covert ways in which whiteness expresses itself, but often go unnoticed, unrecognized. Part of this, of course, is how power structures work. White supremacist discourse attempts to conceal its socially constructed origins. So, we must trace whiteness, name its power to obfuscate its privilege and its historicity. I feel called to action to deploy theory in the name of undoing white supremacy, white normativity, and its violence. What does a call to action regarding anti-ableism look like? What does it entail? In short, what might readers of this conversation do to undo ableism and fight against its manifestations of violence?

Disability and ableism can serve as the tie that holds oppressed communities together, or the wedge that pits us against each other. Developing an anti-ableist lens and praxis lends itself to powerful cross-community solidarity and leads to incredible cross-community victories. We have a lot of work to do, however. Ableism, and the disability consciousness gap within and across social justice movements, has led and continues to lead to oppressed communities distancing themselves from disability and reinforcing the ableist notion that disability is a valid excuse for people to be exposed to injustice, inequity and violence (e.g., suffragists of the past and prison reformists/abolitionists of the present). The solution, of course, is not to denigrate disabled people, but to debunk and dismantle popularized ableist myths of inferiority, “undeservingness,” invalidity of all oppressed peoples, disabled included.

We all must ardently contest advocacy strategies that tie people’s value to their labor productivity or that establish or reinforce ranking systems of marginalized people. All social justice movements must be intentionally rooted in, at least, anti-ableism, anti-racism, anti-capitalism and anti-imperialism. Incarceration in all its horrific forms must be named, shamed and dismantled. Reparations including guaranteed income, housing, health care, and other social benefits with the attendant and necessary support a person, family and community needs, should be requisite for all those returning from the various types of incarceration. Those fighting for justice must practice true solidarity. Demonization of any group that is intentionally made politically, socially, economically, or otherwise marginalized fans eugenics flames, reinforces all oppression, and strengthens white supremacy and capitalism’s stranglehold on all oppressed people.

Disability justice offers a good point of entry for many people who are just beginning this inquiry. Like many other Black/Indigenous-, queer-, disabled-developed praxes, disability justice is concerned with the kinship of our identities, communities and struggles (with an intentional centering of those living at the margins of the margins). Disability justice is also concerned with co-creating safety and abundance and destabilizing the foundations of all structures that create and perpetuate domination, exploitation, violence and inequity. Angela Davis notes that “for centuries, people have been unwilling to grasp the concept that only by undoing the foundation can we build a new future.” Ableism is the foundation that must be torn asunder. Developing a strong disability politic and anti-ableist praxis is one way to counteract power holders’ centuries-long efforts to sustain inequity and pit oppressed communities against each other.

Considering the extent to which the united states’ legal, medical, political, economic and social systems depend on disability and ableism, let us commit to at least the following:

- Develop a nuanced and expansive understanding of disability and ableism, studying their relationship with/in and to power, systems of oppression, domination, white supremacy, racial capitalism, settler colonialism, imperialism, law, medicine, and more. Integrate an analysis of disability and ableism into your everyday life, practice, work, etc.

- Assess how your communities/the communities you serve are categorized, criminalized, pathologized, or are otherwise deemed undesirable, unworthy, disposable, etc. Identify how these categorizations are connected to disability, anti-Blackness, ableism, eugenics, etc. (past and present)

- Identify how your community is seemingly pushed toward ableism in efforts to defend its humanity and find ways to center anti-ableism and cross-community solidarity instead.

- Assess how disability and ableism are implicated in and/or informing your advocacy (e.g., how is ableism showing up in the laws you follow and cite, the practices you engage in, the “alternatives” you propose, etc.).

- Identify common and overlapping issues and struggles within and across communities (disabled and nondisabled, for example). You might begin by asking these or similar questions: Who was/is categorized together? How were/are these identities created/defined/manufactured? What claims were/are made about heredity? What were/are acceptable actions in response to these categorizations/heredities? How are different communities similarly/differently affected by this particular issue?

- Create access-centered practices and study and internalize disability justice to build a stronger movement and bring those who are not considered within your own community or who exist at the margins of your community to the center. Ensure your thought, work, movements are centering ableism, disability and disabled people.

- Develop a disability politic and anti-ableist framework that invites and demands solidarity across identities, communities and movements. (Always center the “margins of the margins.”)

- Do not erase disabled identities of Black/Indigenous/negatively racialized ancestors. Honor the whole humanity of those who came before us by naming their disabilities in addition to their other identities. Take note how their disabilities in/formed their lives, perspectives, freedom dreams and work.

- For those in principled struggle: pace yourself, give yourself and others grace, take time for rest and pleasure, ever-evolve and create your own heart- and humanity-centered metrics of “success.”

- And finally, and perhaps most importantly, Black/Indigenous and other negatively racialized folks who have disabilities, there is a home for you with your Black/Indigenous disabled kin that requires nothing of you but your existence. Come home.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.