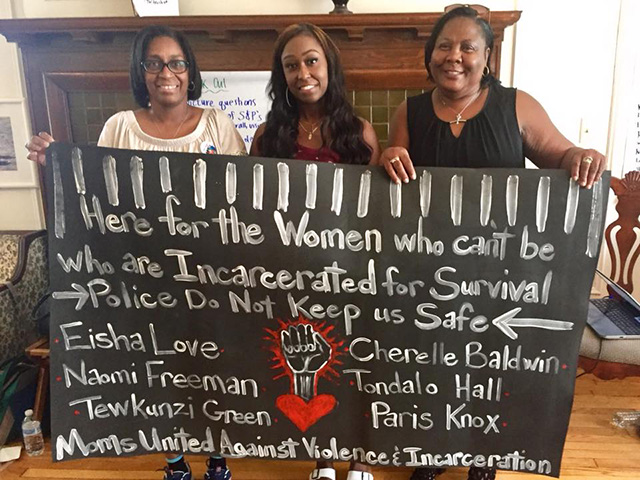

Cherelle Baldwin (center), Baldwin’s mother Cynthia Long (left) and organizer Mary Shields from California Coalition of Women Prisoners (right) hold a banner prepared by Moms United Against Violence and Incarceration, which lists the names of criminalized survivors. (Photo: Holly Krig)

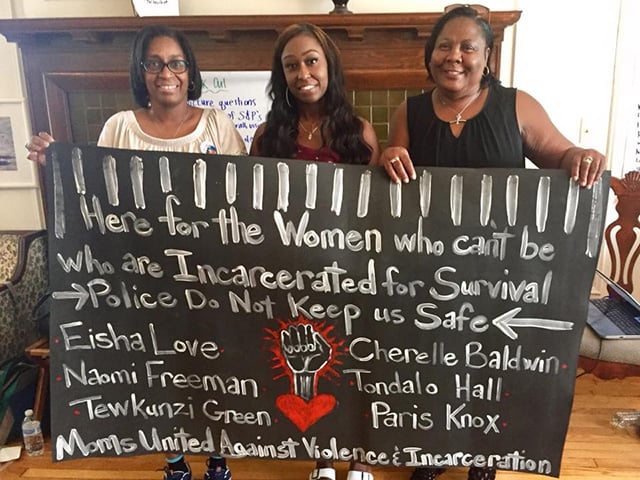

Cherelle Baldwin (center), Baldwin’s mother Cynthia Long (left) and organizer Mary Shields from California Coalition of Women Prisoners (right) hold a banner prepared by Moms United Against Violence and Incarceration, which lists the names of criminalized survivors. (Photo: Holly Krig)

Friday morning, January 26, 2018, Paris Knox arrived at the Leighton Criminal Courthouse, or what’s called “the bullpen.” There, people incarcerated pre-trial at Chicago’s Cook County Jail travel through tunnels to the courts in the early morning, long before judges, attorneys and supporters, if they have them. Paris was excited, having given those she was leaving behind her soap, toothpaste, pads, books — everything but the letters and cards written to her over the last year back at Cook County Jail. Paris had been incarcerated nearly 13 years, most of which she spent in prison at Dwight Correctional Center and finally Logan Correctional Center. Approximately 2,000 women are incarcerated at Logan, most of whom are also survivors of domestic violence or violence in childhood.

In 2005, Paris Knox was arrested for the outcome of an action taken in defense of her life, while home with her infant, resulting in the death of her former boyfriend. Paris was charged with first-degree murder and sentenced to 40 years in prison, separated from her child. In 2017, she returned to Cook County Jail, having won her appeal, only to have the state decide to pursue first-degree murder charges again.

That Friday, those of us supporting Paris were about 10 strong inside Judge Charles Burns’s courtroom. Our group included Paris’s mom, Debbie Buntyn; myself, cofounder of Moms United Against Violence and Incarceration, which has operated, in part, as a defense committee for Paris; and Monica Cosby, a Moms United organizer, released in 2015 after 20 years of incarceration for the actions of her abuser. We were emboldened by co-strugglers all over the country, many working under the banner of a new organization called Survived and Punished.

Chicago is notorious for abuse by police, from the 1937 Memorial Day Massacre to the 1968 Democratic National Convention, to then-detective Jon Burge’s torture of Black women and men. More recently, the Chicago Police Department killings of Rekia Boyd, Dakota Bright, Ronald Johnson, Quintonio LeGrier, Bettie Jones, Desean Pittman, Roshad McIntosh, Laquan McDonald and others have drawn national attention.

Fewer people know about the survivors of sexual violence, like Tiawanda Moore, or (Trina) Kim Townsend, who were each assaulted by Chicago police officers. Tiawanda herself was charged and prosecuted when she tried to record police authorities refusing to help her file a complaint about that assault. Kim was a minor when she was repeatedly assaulted by a neighborhood cop, an “officer friendly.” Probably, no one outside her community heard the story of 10-year-old Naomi Freeman who, in 2003, was stopped on her way home from school by a police officer who searched her book bag and shoved her head against a brick wall when she protested.

In domestic violence situations, people often ask why survivors of violence have not called the police. Often, they have, and have received no useful response. Sometimes they have not: There is risk in calling police. Many survivors fear the police themselves, and for good reason, as the experiences of Tiawanda Moore, Kim Townsend and Naomi Freeman demonstrate. Others are worried that a call to 911 will violate a law that exists in a number of states, in which landlords or housing authorities can claim police visits to a home constitute a nuisance, and is grounds for eviction. Survivors may also face coercion to press charges and assist the prosecutor, as they can be subpoenaed or charged with contempt if they are too afraid to testify or simply do not want their partner to go to jail. Anyway, the involvement of police and courts is no guarantee that future violence will be prevented. Paris Knox, for example, had a police report detailing the violence her abuser had already perpetrated, but when she was arrested for defending herself, she was still charged with first-degree murder.

A win inside a violent system can only ever be relative.

Paris is not alone in this catch-22. When survivors like Marissa Alexander, Bresha Meadows, Cherelle Baldwin, Tewkunzi Green, CeCe McDonald, Gigi Thomas, Ky Peterson (and so many more whose names we may never know) took action in defense of their lives, they were their only protection.

Criminalization systems — police, courts, jails, prisons, immigration authorities, child protection agencies — draw lines between grieving sides, overrule the complexity of abuse and trauma, take advantage of the pain of grieving families and punish survivors. These systems target Black, immigrant, Native, poor, disabled, trans and gender nonconforming people, demanding that survival be possible only under the conditions of domination and exploitation. The victory is only and always for the system itself.

But, where survival has been dishonored and punished by these systems, there is a growing resistance, taking many forms, including mutual support and organized solidarity with and for survivors. A few criminalized survivors have been supported by more mainstream domestic violence organizations, but this organizing is largely volunteer-driven, taking the form of defense committees that center the needs of the survivors themselves. That kind of community-based organizing, led by Assata’s Daughters, drove out a notorious State’s Attorney, Anita Alvarez, (who prosecuted Tiawanda Moore), in the #ByeAnita campaign.

Consider the story of Cherelle Baldwin, a young Black woman who in 2013, after being choked by her ex-boyfriend with his belt, her leg broken and her toddler sleeping inside, did the only thing she could to ensure he would not kill her. As a result, she was locked up in a Connecticut prison. When I heard about Cherelle’s incarceration, I searched for information about a solidarity campaign to support her. Finding nothing, we at Moms United emailed Cherelle’s attorney, Miles Gerety, looking for a way to support Cherelle remotely, and to advocate for local support. The Chicago-based organization Love & Protect (formerly the Chicago Alliance to Free Marissa Alexander), which hosts letter-writing events to people in prison, encouraged attendees to write to Cherelle. Soon, Cherelle found herself receiving letters from Chicago and around the country. When a letter arrived at our office, it was from Cherelle’s mom, Cynthia Long. Cynthia and Cherelle’s sister, Nickki Monroe, were very interested in organizing support for Cherelle, but were frustrated that no local domestic violence organizations were responsive. There was regular court support from a faith-based group and a committed supporter, Sherry Dimauro, but advocacy groups were not stepping up.

However, local support grew as we worked with Cherelle’s family and attorney to circulate a petition demanding that the state’s attorney’s office drop the charges. We organized social media events with organizers from the Stand with Nan-Hui campaign in California. Journalists, particularly Melissa Jeltsen of HuffPost, wrote articles about Cherelle and followed her case in court.

In early 2016, Cherelle was acquitted on all charges. Afterwards, supporting groups organized a reentry fundraiser that raised over $11,000 from 327 donors for Cherelle. The fundraising campaign served as another opportunity to talk about how these cases are not unique: They most often result in convictions, so we cannot count on courts to set people free. Cherelle’s mom Cynthia is now working to bring together more moms and survivors, and to fill the gaps where local support was lacking for Cherelle. The impact of organizing alongside survivors, moms, sisters and community is exponential.

Back in Chicago, in the summer of 2015, a young, Black mother named Naomi Freeman — who 12 years before had experienced violence at the hands of the police — sat in Cook County Jail, charged with first-degree murder for defending her life in the face of life-threatening abuse. Her bond was high — $35,000 would be required for her release. She was pregnant. Alexis Mansfield, an attorney from Chicago Legal Advocacy for Incarcerated Mothers, met with Naomi. Later, I visited Naomi, and met her mom and her attorney.

Beyond their individual successes, these campaigns educated a much broader portion of the public about criminalized survival.

In late fall of 2015, Moms United and Love & Protect composed a letter to the state’s attorney’s office demanding Naomi’s release, signed by numerous organizations around the country, including local groups Chicago Community Bond Fund (CCBF), Lifted Voices, Let Us Breathe Collective, Black Lives Matter-Chicago, Nehemiah Trinity Rising and Chicago Metropolitan Battered Women’s Network. This was a demand for Naomi’s freedom. It was also preparation for a campaign to raise the $35,000 needed for Naomi’s pre-trial release, which would not only allow Naomi to give birth outside of jail, but improve her ability to fight for her freedom.

On December 23, 2015, CCBF posted Naomi’s bond, after a public campaign that raised $10,000 just before the holidays, along with $25,000 from Chicago’s Women’s Justice Fund. The fundraising effort was supported by a direct action organized by Lifted Voices, in which 16 women and non-binary people of color laid down at the busy intersection of Congress Parkway and Clark, to draw attention to the murder of Laquan McDonald by Chicago police and the prosecution of Naomi Freeman, who had no reason to believe police would keep her safe.

In January of 2017, as Naomi continued monthly pre-trial trips to the Leighton Criminal Courthouse, which is connected to the jail by walls and tunnels, Paris Knox returned to Cook County jail for a new trial. Between her mom, sister, long-time friends and Moms United, Paris would also have court support at nearly every appearance. Love & Protect would include Paris in letter-writing and other events, some of which her mother attended. Moms United organized book drives to ensure Paris had books and some money to help her transition from having community and a few programs to participate in while she was in prison, to having mostly empty time at Cook County Jail.

In May of 2017, Paris’s mom Debbie spoke at Moms United’s annual Mother’s Day Vigil outside Cook County Jail. Paris happened to call her mom during the vigil, and heard the crowd’s roar of support. The campaign to support Paris was growing.

In the summer of 2017, an event organized by Survived and Punished, entitled “No Perfect Victims,” convened survivors, freedom campaigns, and advocacy and policy organizations from around the country. While there, some of us continued a conversation started a couple months before about taking advantage of the opportunity of a new Cook County state’s attorney to free people criminalized for self-defense, starting with Paris Knox, Naomi Freeman and another survivor named Caress Shumaker. A pre-meeting and strategy session followed.

By early August of 2017, Chicago Metropolitan Battered Women’s Network, Moms United and Paris’s mom met with Assistant State’s Attorney Jennifer Gonzalez to discuss the three cases, to demonstrate their connection to a growing movement, and to argue that action on these cases could be a critical part of the change that Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx intended to bring to her office. Monica Cosby and Debbie Buntyn spoke powerfully. Following this group meeting, each of the defense attorneys would meet with Gonzalez and the respective prosecutors on each of the cases. Naomi’s attorney created a “mitigation packet” for the meeting, which gives context to a criminalized act — both an explanation of the circumstances and demonstrates support for the defendant. It included articles written by Victoria Law, Kelly Hayes and DNAChicago; images from public actions and letters of support; and notes from an expert witness.

By September of 2017, two of these three women, each charged with first-degree murder and facing decades in prison, would see charges reduced or dismissed completely.

Naomi Freeman was offered a plea deal of an involuntary manslaughter charge, with 30 months of probation and a stipulation of a monthly visit to a mental health professional. Debbie, Paris’s mom, was in court for her daughter on that day, and joined us to congratulate Naomi and offer her support in the days ahead, which she continues to give.

Mass participatory defense work as part of a larger campaign against both gender-based violence and criminalization is rich with history and possibility.

Caress Shumaker’s charges were dismissed entirely. Caress had already spent two years in pre-trial detention, separated from her family. Caress’s attorney Rachel White-Domain described the scene in “the bullpen” when Caress learned this news: Caress fell to the floor, and cheering erupted from a choir of people dressed in orange, tan and blue jumpsuits, awaiting their own cases to be called.

On February 13, 2018, Judge Burns signed off on a plea deal that reduced Paris’s charge to second-degree murder, with “time served.” This means that after nearly 13 years incarcerated for defending her life, Paris will soon be home.

While no conviction or period of confinement is a reasonable consequence for defending one’s life, we as organizers consider these outcomes wins, because they mean these women will not be spending decades (or decades more) in prison. A win inside a violent system can only ever be relative. As Mariame Kaba, founder of Project NIA and co-founder of Love & Protect and Survived and Punished, says, we must “prefigure the world we want to live in.” Gender-based violence has been enforced by agents of state violence and institutionalized in the form of prisons and jails, as well as in wage gaps, poverty rates and service agencies purporting to protect children by punishing mothers. Criminalization has not made anyone safer.

The stories that led to the release of Cherelle Baldwin, Naomi Freeman, Paris Knox and Caress Shumaker are important on multiple levels. The lives and experiences of these four young Black women are different, but they intersected at the state’s decision to criminalize their survival — an old and persistent story. Their stories also intersect because they all involve organized solidarity efforts built upon mass participatory defense campaigns. Beyond their individual successes, these campaigns educated a much broader portion of the public about criminalized survival, investing people in honoring that survival, not punishing it. Building on previous campaigns like the nationwide effort to free survivor Marissa Alexander, these efforts have also challenged people to think about all of incarceration as a criminalization of survivors of one form of violence or another, whether that violence be family-based violence, police violence or the violence that is poverty.

We must ensure all of these survivors continue to get free, and have the chance to share their stories and uplift one another, as many have and do. But survival demands nothing more than to keep surviving, and that looks different for each person. To paraphrase Audre Lourde, defending one’s safety and survival — especially for Black, immigrant, Native women and gender non-conforming people targeted by state violence — is a radical act. Honoring, uplifting and actively defending the right to that survival is revolutionary organizing.

Mass participatory defense work as part of a larger campaign against both gender-based violence and criminalization is rich with history and possibility. And this struggle must be broad-based, intersecting with other movements. For example, the labor movement must honor the crucial contributions of sex workers’ rights groups — who are also leading freedom campaigns in defense of criminalized survivors — uplifting lives of people not only as workers, but as co-strugglers in a bigger fight. Our defense work must include Water Protectors and Land Protectors, who know that gender-based violence erupts along extraction sites, and that prisons and jails and capitalism involve the institutionalization of both sexual violence and environmental racism.

Community is our power, and community includes all those extracted by criminalization.

Free them all.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.