Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

James Dixon has recently made a plea for 12 years in prison for his killing of a trans woman, Islan Nettles, in Harlem on August 17, 2013. As he restated at trial, Dixon killed Nettles because he had hollered at her and was mocked by his friends, who guessed that Nettles was trans, for doing so. It apparently enraged him because a similar incident had happened to him recently when he flirted with two women who turned out to be transgender. The conviction comes after initially arresting the wrong man and years of mourning and protests. I was there at the controversial first memorial, where our “allies” misgendered and otherwise disrespected our fallen sister, and I made it out on that cold day in January 2014 to protest at One Police Plaza, the headquarters of the New York City Police Department.

The author and fellow trans activists Annie Danger and Bahar Akyurtlu at the One Police Plaza protest for the death of Islan Nettles, January 2014. (Credit: Emma Caterine)

The author and fellow trans activists Annie Danger and Bahar Akyurtlu at the One Police Plaza protest for the death of Islan Nettles, January 2014. (Credit: Emma Caterine)

While I did not know Islan Nettles, I knew many who did, and the pain has been visceral. I hope the end of the circus around Dixon’s prosecution will allow those who were close to her to heal.

Focusing on individual murderers and their incarceration will never prevent the murder of trans people.

Some have already praised this as “justice,” but others have said it was an injustice that Dixon was not charged with a hate crime or with murder. As a prison abolitionist, I agree with neither of these assessments. These narratives told by much of the media — including the LGBTQ media — around the murders of trans people in the United States are not grounded in facts. Bound up in government fearmongering and neoliberal politics, the narrative of trans murder perpetuates the following misconceptions and myths:

Myth 1: Since trans people are murdered in the streets, we need more police to protect us.

Myth 2: Since trans murders are not taken seriously by the criminal legal system, we need to pressure district attorney’s offices to investigate our murders.

Myth 3: The more severe the charge, the more justice is served, and prosecutors are not getting severe enough charges, especially with hate crimes.

This piece will prove the falseness of these three myths specifically in the context of the United States, using data from 2012 to 2016. In many other places, including Brazil and Jamaica, the situation is different because trans people are often killed by police officers themselves. But looking specifically at the situation in the United States reveals an important reality: Even when police and prosecutors are doing everything “right,” their goal is not to protect and serve, but rather to incarcerate, repress and terrorize.

Focusing on individual murderers and their incarceration will never prevent the murder of trans people. Instead, we should be uprooting the transphobic ideas that pervade corporate policy, the dominant media, public policy, religion and workplaces.

While some murders of trans people are random attacks by bigots, most murders are related to domestic or sexual violence, similar to most murders of cisgender women. Thus studying the copious statistics on how the police and prosecutors handle domestic violence murders of cis women will help reveal how much the criminal legal system could or could not help prevent the murder of trans people — even if they were to “do their jobs.”

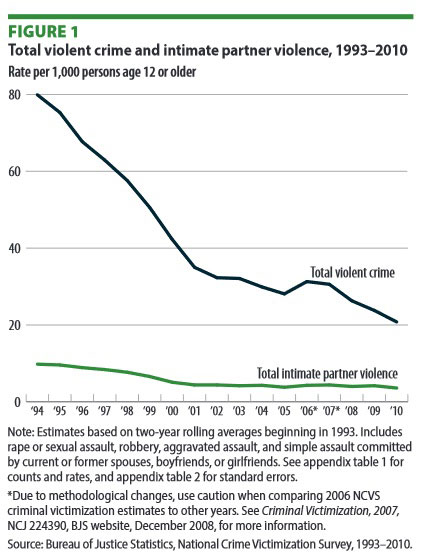

While total intimate partner violence has decreased over the past couple of decades, it has increased as a percentage of the total violent crime committed. The rate fluctuates only minimally over the past few years, even as total violent crime keeps a steady course downward.

(Credit: US Department of Justice Special Report on Intimate Partner Violence, 1993–2010)Some will be quick to credit the decrease, however small, to the Violence Against Women Act and the increased enforcement of mandatory arrest policies. There were several high-profile cases over the past few decades in which women sought out aid for themselves and their children in the face of domestic violence, sometimes in the form of a restraining order or custody settlement. When the abusive partner disobeyed these government orders, women often found police officers reluctant or even combative about getting them enforced, which in some cases contributed to gruesome violence.

(Credit: US Department of Justice Special Report on Intimate Partner Violence, 1993–2010)Some will be quick to credit the decrease, however small, to the Violence Against Women Act and the increased enforcement of mandatory arrest policies. There were several high-profile cases over the past few decades in which women sought out aid for themselves and their children in the face of domestic violence, sometimes in the form of a restraining order or custody settlement. When the abusive partner disobeyed these government orders, women often found police officers reluctant or even combative about getting them enforced, which in some cases contributed to gruesome violence.

In response, some feminists put forward mandatory arrest policies, where police officers are required to make arrests when answering certain kinds of domestic disturbances. But the flawed assumption is that it will always be immediately clear to the police who should be arrested. For some of society’s most marginalized women, including trans women, the mandatory arrest policies implemented for domestic violence prevention have resulted in dual arrests, where both people are arrested because the “primary aggressor” cannot be determined.

There is good reason for the trans community to think that our lives do not matter to those in power.

Moreover, US police officers engage in high rates of domestic violence themselves. Domestic violence survivors need to be able to seek out aid and protection — and within our current structures, sometimes calling the police feels like one’s only option. Yet there is only so much relief that survivors can garner from a criminal legal system constructed for the purpose of incarceration and punishment. Can we trust that the system is working to protect survivors when 75 percent of women in New York prisons have had experiences with domestic violence? A police force that is 87 percent male and 88 percent white is unlikely to intervene in a constructive way to protect trans women of color from domestic violence. Vulnerable trans people often lead criminalized lives of being homeless, dealing drugs or doing sex work, and in these cases, the police are decidedly not their saviors: They are all too frequently the abusers themselves.

Upon the murder of a trans person, police and prosecutors often twist the knife by using the murder victim’s former name, using incorrect gender pronouns or mislabeling them as a “cross-dresser” or “transvestite.” There is good reason for the trans community to think that our lives do not matter to those in power. However, those in power in the criminal legal system do care about meeting quotas and prosecuting high-profile cases. They have actually investigated the murders of trans people with a lot of success over the past few years.

Prosecutors have charged or convicted someone in 63 percent of reported murders of trans people, almost identical to the 64.1 percent of murders that occur in the general population, over the past four years. The rate has been climbing: It was 50 percent in 2014; 66.7 percent in 2015; and thus far, 100 percent in 2016. And the average is thrown off by regional differences: Maryland in particular has the worst rate, at 40 percent. But the two states with the most trans murders, California and Ohio, have rates of 89.9 percent and 83.3 percent, respectively. If proper investigations resulting in charges or convictions helped to prevent murder, why do the two states with the most murders also have some of the highest rates of charges and convictions?

The man who murdered Islan Nettles, James Dixon, took a plea deal for manslaughter. While some trans activists have alleged that the relatively low severity of the sentence against Dixon is a result of the criminal legal system treating trans victims differently, it more likely has to do with the complications. The police initially arrested Dixon’s friend Paris Wilson, and only released him when Dixon turned himself in. Evidence was sparse because of broken cameras at the nearby Housing Authority Police precinct, and Dixon and his lawyer understood this well enough to leverage a better deal than the initial 25 years he was offered. But Dixon’s case is an outlier; most of the convictions of those who have murdered trans people are some of the harshest in the country. From 2012 to today, prosecutors have secured four life sentences, and several convictions falling between 20 and 60 years. Further, it is important to view these sentences in the context of how egregiously inhumane the lengths of US prison sentences are in general. These decades-long, and sometimes lifelong, sentences persist, even though long sentences have failed to show an effect of deterring crime.

I have had the enormous privilege to be part of the birth of the modern trans rights movement. We are an incredibly diverse group of people, touching on every intersection of oppression and tapping into a vast base of knowledge and skills. And while there are some exceptions and plenty of mistakes, we tend to be on the side of oppressed people all around the world. It is our greatest strength and a critical one: We are far too small of a group to be able to exercise serious political power outside of the coalitions we can form with other groups. That is why we must approach our relationship to the criminal legal system with great care.

I do not want to downplay in any way how depraved these killings are, or to disregard the righteous anger at those who commit them. After all, the statements of James Dixon at trial lacked remorse for the violence he committed to protect his fragile, transphobic masculinity. But Dixon’s lack of accountability is exactly why I cannot call his conviction “justice.” None of the hate in his heart has been extinguished, and the trans women who will surely be in the same prison as Dixon and others like him often get de facto solitary confinement and risk of sexual assault added to their punishment.

An emphasis on prosecutions and convictions distracts from what should be the central aim of the trans movement: actually ending the epidemic of violence against trans women of color and other trans people.

Incarceration is the solution offered when it is already too late. We need to have enough power to stop media portrayals of us as monsters. We need to start at the root of this violence: the bathroom bills that criminalize our mere public existence, housing policies that are really only good at housing us in prison, the criminalization of sex work, and insecure employment paying poverty wages that make us four times more likely to experience poverty.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.