Cafeteria workers in New Orleans are working to organize a union in order to negotiate for better wages and working conditions with Volunteers of America, a wealthy Christian ministry contracting with local elementary schools to provide meals to students. From left to right: Damita Hall, Pamela Bourgois, Quintessa Dampeer and Debra Slaughter. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

Cafeteria workers in New Orleans are working to organize a union in order to negotiate for better wages and working conditions with Volunteers of America, a wealthy Christian ministry contracting with local elementary schools to provide meals to students. From left to right: Damita Hall, Pamela Bourgois, Quintessa Dampeer and Debra Slaughter. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

This story has been updated.

It’s the steamy first week of August in New Orleans, and a number of charter elementary schools are already welcoming students back from a brief summer vacation. I’ve volunteered to help make lunch. At 8 a.m. I arrive at a kitchen located in a revamped warehouse along the Mississippi River that once housed a cotton press dating back to the 19th century. I sign my name on a volunteer list, don a hair net and get to work. One of the women I’m working with adds a dash of seasoning to a mound of green beans, and we begin scooping servings into little trays already full of shepherd’s pie. The meals are then trucked to school cafeterias, heated and served.

The school lunch service is called Fresh Food Factor, and pictures of children holding vegetables in a garden hang in its brightly lit office. The brochure says school administrators are under “increasing pressure” to cut costs, so the program provides a “viable alternative to the quick fix of processed foods” offered by other vendors. Some lower-income neighborhoods in New Orleans are considered food deserts due to a lack of affordable grocers, so serving healthy food in schools can provide kids with options that they may not always have at home.

Fresh Food Factor is run by the local chapter of Volunteers of America, a multimillion-dollar Christian ministry that runs halfway houses, shelters, food banks, drug treatment programs and housing projects nationwide, often with government funding. For right-wing champions of charter schools, such as Betsy DeVos, President Trump’s controversial education secretary, Fresh Food Factor would be a shining example for the rest of the country: a religious group serving healthy meals at charter schools that chose to partner with a civic-minded contractor. Democrats would be happy to know that the food service helps schools comply with nutrition standards established by Michelle Obama — standards that the Trump administration recently scaled back.

Despite its parent organization’s name, most Fresh Food Factor workers are not volunteers like me. Employees who cook in the warehouse kitchen or serve students in schools receive wages that start at $9 per hour. Some work full-time, but the food service relies on part-time workers and a smattering of volunteers to fill the gaps. Besides managers and truck drivers, most employees are women of color, the workers commonly called “lunch ladies” who are inseparable from mealtime in public schools. As we wrap dozens of veggie eggrolls in sheets of shiny foil, one part-time kitchen employee tells me that she is not scheduled for enough hours to make ends meet and is looking for additional work, a common story in a local economy built on tourism and low-wage service industry jobs.

Before Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans’ school cafeteria workers and janitors were unionized and enjoyed the same benefits as teachers, including paid vacation and time off during the summers, according to LaTanja Silvester, president of the local Service Employees International Union (SEIU) office. After the storm devastated the city, the state took over the school board and began an unprecedented experiment in school privatization, dismantling the teachers union and firing 7,000 school employees in the process, many of them Black women. Cafeteria workers now work for competing contractors that offer varying pay scales and benefits. Sometimes, benefits like paid sick days aren’t offered at all.

“Volunteers of America advocates for alleviating poverty, when in fact the jobs they are providing at the Fresh Food Factor are actually poverty-wage jobs,” Silvester told Truthout, adding that SEIU is currently working with employees seeking union representation despite “pushback” from Volunteers of America.

Pamela Bourgois and Damita Hall, Fresh Food Factor employees who serve lunch at Encore Academy, a local charter elementary school, told Truthout they were regularly expected to work off the clock for no additional pay until they began organizing a union and standing up for their rights on the job. Proper safety supplies such as arm-length oven mitts are not provided, leaving some workers to choose between paying for their own safety gear or burning themselves on hot trays. Only full-time managers and lead workers are offered health care benefits, and Bourgois says she has only received one raise in three years. Spokespeople for the New Orleans chapter did not provide a response to several inquiries from Truthout.

Encore Academy is the charter elementary school in New Orleans where Damita Hall and Pamela Bourgois work in the cafeteria. Under the charter system, students are not assigned to a school based on where they live. Instead, parents submit applications with a list of schools ranked from their top choice on down, aware that their child may not be admitted to the school they like best. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

Encore Academy is the charter elementary school in New Orleans where Damita Hall and Pamela Bourgois work in the cafeteria. Under the charter system, students are not assigned to a school based on where they live. Instead, parents submit applications with a list of schools ranked from their top choice on down, aware that their child may not be admitted to the school they like best. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

New Orleans charter schools hire food service contractors like Volunteers of America with money from state and federal school lunch programs because so many students qualify for the subsidies. In 2016, Volunteers of America Greater New Orleans received 59 percent of its $32 million in revenue from state and federal grants and contracts, according to an annual report released by the group. Nationally, Volunteers of America brought in nearly $312 million in total revenue last year.

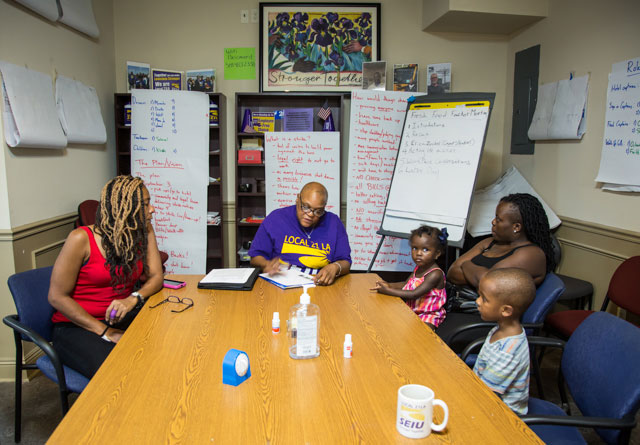

New Orleans cafeteria workers meet at the local union office. Some school employees work multiple jobs to make ends meet and have children and grandchildren attending charter schools. (Photo: Julie Dermanksy)

New Orleans cafeteria workers meet at the local union office. Some school employees work multiple jobs to make ends meet and have children and grandchildren attending charter schools. (Photo: Julie Dermanksy)

Hall says Volunteers of America has responded to their push for union representation with SEIU by hiring a lawyer and deploying other “intimidation tactics.” She received a disciplinary write-up for “petty stuff” on the first day of school this year. Still, the women see their jobs as crucial for making sure students are able to learn in class — something that’s hard to do if you’re feeling hungry. After all, their own children attended public schools in New Orleans, and now their grandchildren attend charter elementary schools.

“In our position, we know that we are very instrumental in the kids’ daily process … we should be treated better than this, more fairly and justly than what we are,” Bourgois says.

***

Betsy DeVos, the wealthy charter school advocate who survived a razor-thin Senate confirmation vote to become US secretary of education earlier this year, has reignited a fierce national debate over school privatization. Now, all eyes are on New Orleans, where critics say the nation’s most complete charter experiment is steeped in structural racism.

After the floods of Katrina were finally cleared, the state legislature and a state board elected by Louisiana’s white majority took over the New Orleans school system from the local board elected by the city’s Black majority. In the decade since, schools have closed, consolidated and been handed over to private companies and nonprofits. Now, 92 percent of New Orleans students are enrolled in schools run by charter boards, more than any other urban district in the country.

Test scores and graduation rates have markedly improved over the past decade in one of the nation’s lowest-performing districts. However, rates of student achievement had nowhere to go but up, and researchers are hesitant to give school privatization full credit for improvements in performance. They say other factors, such as strong incentives to “teach to the test,” a $1,000 increase in per pupil spending relative to other districts and the fact that some lower-income students did not return after being displaced by Katrina, must be considered before New Orleans schools are held up as a model for other systems.

At the same time, a federal lawsuit and a list of civil rights complaints have been filed on behalf of immigrant students, students of color and students with disabilities who were denied access to public education because schools had discriminatory enrollment and disciplinary policies, or were simply inaccessible. Many students travel across town to attend class, and schools buy ads on billboards and buses all over the city, while neighborhood schools are often neglected or abandoned. Schools in working-class Black areas are shuttered when students fail to perform on high-stakes standardized tests, leaving empty buildings where neighborhood institutions once stood.

“You label our schools as failing, when in fact it is the system that has failed us, because we never addressed [Brown v. Board of Education], we never made education equal,” says Jitu Brown, national director of Journey4Justice Alliance, a coalition of groups from Black and Brown communities impacted by charter schools, including New Orleans.

Fencing blocks access to John McDonogh High School in New Orleans, which has been closed since 2014. Charter schools are shuttered when students fail to perform on high-stakes standardized tests, leaving empty buildings where neighborhood institutions once stood. Many students commute across town to attend class. (Photo: Mike Ludwig)

Fencing blocks access to John McDonogh High School in New Orleans, which has been closed since 2014. Charter schools are shuttered when students fail to perform on high-stakes standardized tests, leaving empty buildings where neighborhood institutions once stood. Many students commute across town to attend class. (Photo: Mike Ludwig)

Brown says the Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 decision may have ended the “separate but equal” doctrine of school segregation, but equality has yet to be realized. After convincing two Republican senators to flip and oppose DeVos, who was only confirmed after Vice President Mike Pence cast a tie-breaking vote, Brown and other organizers realized what was missing from the progressive education movement: multiracial coalitions led by the people of color who are impacted most. Activists are currently conducting an “equity assessment” of public schools nationwide to prove just that. The assessment is part of the #WeChoose campaign, a nationwide push for racial justice and sustainable community schools that grew out of efforts to block DeVos’s nomination.

“Equity is not just funding,” Brown tells Truthout. “It’s about expectations, it’s about curriculums and how discipline is administered, and we will demonstrate through this assessment that the issue is inequity. It’s not bad teachers, it’s not bad students from the inner city, it’s not disinterested ghetto parents.”

Brown says the movement is not railing against individual charter schools, unless they have discriminatory enrollment and disciplinary policies. Some charter schools do embrace progressive policies; for example, one New Orleans elementary school is committed to enrolling a student body that reflects the neighborhood around it, a working-class area with a mix of Black, white and Latino families. However, this diversity policy does not come without controversy and has made the school highly coveted among parents jostling for enrollment spots in a system based on market competition, making it difficult to get into.

“We don’t have a problem with charter schools, we have a problem with the charter movement and charter market, which is concentrated in our communities,” Brown says. “If charters were so great, white folks would have them, but they don’t get charters. They get magnet schools and well-funded neighborhood schools.”

Before Katrina, New Orleans schools were heavily segregated by wealth and income, and a recent Tulane University study found that the demographic breakdown of the city’s elementary schools has not changed. There have been some changes in high schools, with segregation increasing for low-income students but decreasing for those with special needs. In New Orleans, students are not assigned to a school based on where they live. Instead, parents submit applications with a list of schools ranked from their top choice on down, aware that their child may not be admitted to the school they like best. Black students and activists criticize some charters for enrollment schemes and zero-tolerance disciplinary policies that favor white, abled and wealthier students while keeping — or kicking — others out. They say the idea of “school choice” promoted by DeVos is a myth.

Researchers have found that zero-tolerance discipline disproportionately impacts students on the margins, particularly children of color and children with “non-apparent” psychiatric and intellectual disabilities. Charters in cities like New Orleans are incentivized to enroll students who will improve the school’s overall performance. Lower-performing students can become targets for punishments that ultimately do not correct behavior, but “reinforce toxic interactions and reproduce cycles of perceived misbehavior,” according to the Ruderman Family Foundation. As punishment escalates, students are pushed out of school, where they are more likely to fall into the juvenile legal system and the school-to-prison pipeline.

The New Orleans system is now working toward “reunification” under one local board and says it is addressing concerns about admissions, suspensions and expulsions by centralizing procedures for some schools, but emotions remain raw. In June, the NAACP held a listening session in New Orleans that became increasingly heated as Black students and parents aired their frustrations about living in the petri dish of an unprecedented charter experiment. They lamented the inconsistent stream of teachers from other parts of the country brought in by Teach for America, the organization that has long been criticized for replacing local teachers with lightly trained outsiders who are disconnected from local culture. They questioned how working parents are supposed to stay involved in education when the schools their kids are admitted to are miles from home.

In an especially powerful moment, a group of young students took the microphone despite protests from moderators, declaring themselves experts in the subject of education because they attend school day in and day out. Their school is one of the last remaining traditional public schools in the city, and they are worried about their futures as it faces privatization. “You don’t attend the school, you’re not there every day,” one student said. “The Teach for America teachers don’t care about us, charter schools don’t care about us, and our futures are at stake.”

The students were members of Rethink, a local group that empowers young people to have a voice in changing schools and other institutions. Rethink member Big Sister Love Rush, who recently graduated from a New Orleans high school at the top of her class, got involved after learning that her alma mater would be shutting down this year. After attending public meetings on charter controversies, Love Rush penned a blog post explaining how pro-charter forces take education “out of the hands of parents, like my mother” and give power to outsiders who “act like [students] have no expertise”:

Through all these meetings I keep thinking, who is profiting? Who wins when my school is closed? Who succeeds when conversations about education don’t include and aren’t centered around students, families and teachers? Who benefits when groups are examining the damage of privatized schools on students without any plan on how to stop that damage? Who is aided when discussions become pep rallies? Who makes the money when schools become sites to make a profit?

The disconnect between students and school administrators can be traced back to the firing of 7,000 school employees after Katrina, a move that ripped members of the local community out of their educational institutions at a time when thousands of families had been displaced by a natural disaster. LaTanja Silvester at SEIU says that many food service workers and janitors eventually returned to their jobs, but wages and benefits now vary widely depending on where they work. Many teachers, however, were replaced by a younger, whiter set brought in from out of town through programs such as Teach for America.

Of the roughly 4,300 teachers dismissed after Katrina, 78 percent were woman and 71 percent were Black, according to the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans at Tulane University. About half of this workforce returned to education in the years following the storm, with 37 percent finding jobs in New Orleans and 18 percent working in surrounding areas. These numbers had dropped dramatically by 2013, when only 22 percent of pre-Katrina teachers were still employed in the city’s public schools.

“It’s the colonizing of our communities, where we have people running the quality-of-life institutions in our communities through the way they see us, through their lens,” Brown says.

After Hurricane Katrina devastated the city in 2005, the state dismissed thousands of New Orleans school employees and consolidated schools as it launched an unprecedented experiment in privatization. This school in New Orleans’ Mid-City neighborhood has sat empty since the storm. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

After Hurricane Katrina devastated the city in 2005, the state dismissed thousands of New Orleans school employees and consolidated schools as it launched an unprecedented experiment in privatization. This school in New Orleans’ Mid-City neighborhood has sat empty since the storm. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

New Orleans is at the forefront of a troubling national trend. Brown points to the Albert Shanker Institute, which recently studied nine cities with charter schools in their systems and found that the share of Black teachers in the workforce had declined in every single one over the past decade. Rates varied widely, with Boston and Cleveland losing 1 percent of their Black teachers, while New Orleans and Washington, DC, lost 24 and 28 percent, respectively. Losses in the total numbers of Black teachers in the population were even greater, ranging from 15 percent in New York City to an alarming 62 percent in New Orleans. Seniority-based layoffs had little to do with these declines. Nationally, minority teachers are hired at higher rates than others, but they exit the profession at much higher rates as well.

“The lesson that is being taught all over the United States is that we are not fit to lead, and that is a result of policy,” Brown says.

Black and Brown teachers are more motivated to work with disadvantaged students and hold higher academic expectations for them, which results in better grades and social growth among students, according to the Albert Shanker Institute’s study. Students benefit from teachers of their own race or ethnicity, who can serve as role models and share knowledge about their heritage and culture, the study says.

Love Rush adds that the curriculum itself should also reflect the schools’ populations. She writes that many students want curriculums that “represent us and people like us,” and “that teaches us our true history and the role that it plays in our current lives.” Rethink youth activists are currently campaigning to lower the voting age in New Orleans to 14 so students can have a voice in shaping local politics and the schools they attend.

“We can and will do it,” Love Rush writes. “We will take our education in our own hands because we are the experts of our experience.”

***

The mass teacher dismissal in New Orleans was reflective of a trend that reached far beyond the classroom. Thousands of jobs that supported Black middle-class people vanished at a time when residents were recovering from an unprecedented natural disaster. Some displaced families have still not returned. In the years since, property values in New Orleans have skyrocketed and working-class neighborhoods have become hipster hotspots, putting increasing pressure on lower-income renters in a gentrifying city.

Brown says the gutting of the Black middle class — and the deliberate minimizing of its political power — is not germane to New Orleans, and many of the same cities that have seen a decline in Black teachers have also seen declines in the general Black population. When authorities divest from Black neighborhoods by shutting down their schools and busing children somewhere else, it could be a sign that property in the area may soon become a hot commodity. At a time when the nation is facing a resurgence of overt white supremacy, Brown points out the importance of simultaneously confronting more subtle manifestations of white supremacy.

“I’m a lot more concerned about the white supremacists that are sabotaging our children’s education, that’s white supremacy too,” Brown says. “I’m concerned about the white supremacists that are sabotaging our housing so that we can’t live in our neighborhoods, that’s white supremacy too.”

Back at the Fresh Food Factor kitchen, Volunteers of America’s local “neighborhood development” corporation has established another project in a historic building adjacent to the warehouse where school lunches are prepared: 52 furnished loft apartments complete with a rooftop patio offering a view of the Mississippi River. With help from state and federal tax credits and community block grants, Volunteers of America built these lofts to serve “working households” by creating housing in “emerging neighborhoods” near employers and public transportation, according to the project’s website.

A number of businesses and shops have sprung up in old warehouses and around a nearby Wal-Mart, and public transportation can deliver residents to the downtown business district within minutes. Volunteers of America offers half of the units at lower prices for residents making under $35,000 a year, but rent still ranges from $886 to $950 a month for those who qualify for the discount. With wages ranging from $9 to $14 an hour, kitchen staff would have to spend about 40 to 60 percent of their income to live in their employer’s lofts next door to where they work. Even workers making as much as $34,000 would spend about 30 percent for a single-bedroom apartment, the threshold at which federal authorities consider a household “overburdened.”

Volunteers of America has long been in the “affordable housing” business, using federal housing grants to construct residential buildings for lower-income, disabled and elderly people. The group’s neighborhood development subsidiary in New Orleans, which was created specifically to replace housing post-Katrina, is a nonprofit that has its own for-profit subsidiary for building residences to rent out. Robert Silverman, a professor of urban planning at the University at Buffalo who focuses on the nonprofit sector, said for-profit spinoffs of nonprofit housing initiatives are becoming more common, but profit incentives also raise concerns about “mission drift.”

Volunteers of America is considered a church, so it does not have to file federal tax returns, and it remains unclear how top administrators and property developers are paid for their work.

“It’s kind of a new trend that has been bubbling up over the past six or seven years, where a nonprofit will have a for-profit subsidiary connected to it,” Silverman told Truthout. “Different rules and tax laws apply to each, but they use it as another way to generate revenue [for the parent organization].”

In 2016, Silverman co-authored a study on affordable housing in several US cities with shrinking populations, including New Orleans. In general, affordable housing is not cited near “opportunity areas” as much as observers would like. Single workers and senior citizens tended to have an advantage, while single mothers with children were less likely to find housing near employers or top-performing schools. Volunteers of America and its subsidiaries run housing projects across New Orleans and southern Louisiana, and Silverman said it appears the group is trying to “hit” different income levels. The riverside lofts next to Fresh Food Factor are probably meant for teachers, police, government workers and others with moderate incomes, rather than the low-wage food service workers employed next door.

“The other side of it is, when the nonprofit starts dabbling in these for-profit ventures, it opens up arguments that can be made for why the people working for the nonprofit themselves should be given living wages,” Silverman said.

Pamela Bourgois and Damita Hall just laugh when I tell them how much it would cost to rent a loft apartment next to the kitchen where their coworkers make the lunches they serve. That’s what their employer considers “affordable housing?” LaTanja Silvester at SEIU, on the other hand, is frustrated. She’s sick of seeing workers employed by one school contractor receiving a living wage under a union contract, while workers doing the exact same job for another school must take on additional work just to feed their kids. School privatization in New Orleans may have created a brutal race to the academic top for students, but Silvester says it also created “a race to the bottom.”

“We have to be the city that revamped education and lifted kids out of poverty and provided a pathway for them to be gainfully employed in this country,” Silvester said. “And we must take into account who is providing those services, and they are the mothers of the kids who attend those charter schools.”

Correction: This article originally implied that the student activists who spoke at the NAACP meeting attend charters schools, but in fact they attend one of the few remaining traditional public schools in New Orleans.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $31,000 in the next 48 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.