This article was originally published by the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative news organization based in Washington, D.C.

The Howard R. Young Correctional Institution sits between a creek and Interstate 495 in Wilmington, Delaware. For the last ten years, the prison’s 1,281 residents were counted as constituents of Wilmington’s third city council district.

But when local officials sat down to redraw Wilmington’s city council lines after the 2020 Census, they took a new approach: They counted people in the prison at their last known address in Wilmington — and didn’t count them at all if they hadn’t lived in the city.

“Counting people where they are incarcerated during redistricting, it distorts our system of representative government,” said Wilmington Councilmember Shané Darby, who pushed for the change.

Several states, and a growing number of cities and counties across the U.S., have adopted this reform. They’re seeking to end prison gerrymandering — the term advocates use for counting incarcerated people at the facility where they’re locked up, rather than in their home community. The practice typically dilutes the power of urban areas and communities of color, which see higher rates of incarceration, and at their expense boosts white and rural areas where most prisons are located.

But prison gerrymandering affects more than the representation cities receive in statehouses and Congress, where the issue has drawn significant attention. It also distorts representation within a city, affecting the boundaries that define politics at the local level.

That’s the case in Wilmington, Delaware’s most populous city and one where Black residents make up a majority. The city also has the highest rate of incarceration in the state. And not only does a state prison sit within city limits, Wilmington is also home to a facility for people in substance abuse treatment programs and on work release, which itself has about 150 residents.

Delaware passed a law in 2010 ending prison gerrymandering in state legislative maps — but not in maps for municipal or county governments. That left it up to city and county officials to decide whether to do the same for their local districts.

Predictably, different places made different choices. Now, for the rest of the decade, people in this state will be governed by local maps that follow conflicting standards. This idiosyncrasy extends to several other states, with local officials’ choices on prison gerrymandering typically receiving little scrutiny.

In Wilmington, Darby and other officials voted to follow in the state’s footsteps in September 2021. Darby said the approach was designed to better reflect the city.

“When you divide up communities, you diminish their power and their voice,” she said.

In the city’s third district, that meant subtracting the 1,281 residents at the prison from its population count. But it also required adding back 281 residents of the district who were incarcerated around Delaware — some at the prison in Wilmington, but many in other parts of the state.

Wilmington’s third district, on the city’s east side, had the highest share of Black residents of any of its eight council districts as well as the largest number of residents who are incarcerated in Delaware. Several census tracts within the district have lower median incomes than the city as a whole.

The new approach to map-drawing left Wilmington’s third district with fewer residents than under the old formula. So the committee shifted its boundaries, adding several downtown blocks to ensure it had a population in line with other districts.

The end to prison gerrymandering enjoyed wide support among the politicians redrawing the lines in town.

The city finalized its maps in December 2021, and voters will cast ballots in the new districts for the first time in 2024. Separately, the city council adopted a measure sponsored by Darby to continue drawing maps this way in future cycles of redistricting.

“I was glad that we were able to count folks back in their home district and not overinflate the population of the district that has the facility,” said Dwayne Bensing, legal director of the ACLU of Delaware. In a newspaper editorial, Bensing wrote that Wilmington “avoided a prison gerrymandering fiasco.”

He told the Center for Public Integrity and Bolts that the redrawn districts weren’t likely to lead to huge political changes in the city, but in Wilmington’s compact districts, with about 8,800 people each, it’s a meaningful step.

The new approach “ensures that every person in Wilmington has an equal say in their government,” said Mike Wessler of the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative, which tracks reform efforts across the country.

A Rising Effort to Restrict Prison Gerrymandering

Exploding prison populations in the 1980s and 1990s, fueled by America’s war on drugs, reshaped communities and political maps across the country. They also added weight to the issue of prison gerrymandering.

The city of Anamosa, Iowa, became a poster child for challenges at the local level: In one of its city council districts, about 95% of residents were incarcerated in a state prison. (After a local man won the seat with two votes in 2006, he told a reporter, “Do I consider [incarcerated people] my constituents? … They don’t vote, so, I guess, not really.”)

Prison gerrymandering “distorts our democracy,” Wessler said. “It fundamentally alters political representation, and that harms every single person, whether they live one mile from a prison or 1,000 miles from a prison.” He said local governments were early leaders on the issue, with over 200 adopting reforms in the 2000 and 2010 cycles.

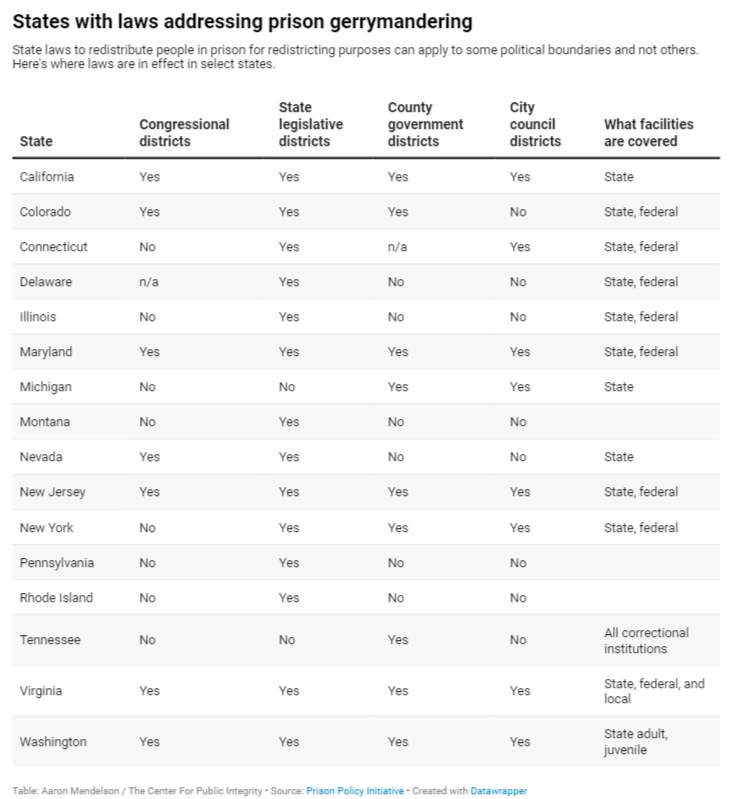

In 2010, New York and Maryland passed laws ending prison gerrymandering at the state legislative level. By the next cycle, a decade later, over a dozen states had passed similar laws.

Nearly half of Americans now live in a state that has taken action to end the practice in drawing statewide maps, the Prison Policy Initiative estimates.

Wessler called the adoption of these laws “a sea change” from the situation two decades ago.

States that ended prison gerrymandering heading into the last redistricting cycle were nearly all run by Democrats, with a wave of newcomers passing the reform in rapid succession over the past four years — including Colorado, New Jersey and Virginia. In these states, with vast disparities in the geography of where people are arrested and where they serve prison terms, legislative maps now count incarcerated people at their last known address.

The issue has attracted attention in some areas that tilt Republican. Earlier this month, Montana’s state Senate passed a bill to end prison gerrymandering after the state’s bipartisan redistricting commission unanimously supported the change.

But any movement to end the practice altogether would have to come at the federal level. With that in mind, a group of three dozen advocacy organizations are calling on the U.S. Department of Commerce to change the tally in the 2030 Census. They write in a letter that “counting incarcerated people at home ensures that communities hit hardest by mass incarceration get equal representation in state and local governments.”

Even Within a State, a Patchwork of Laws

The combination of state and local laws leaves some Americans without any representation.

Take the situation in Delaware. Wilmington ended prison gerrymandering, but Newark, the state’s third most populous city, didn’t. That means a Newark resident incarcerated in Wilmington wouldn’t be counted in a city council district in their hometown — and also wouldn’t be counted in the city where they are incarcerated.

For the purposes of city council representation, they are counted nowhere.

Muddying the waters further: New Castle County, which includes Wilmington, still draws lines for its own districts that count people as living in prison.

“This fits within a broader scheme of a patchwork of laws governing voting rights within the state of Delaware,” said the ACLU’s Bensing. Several states take a scattershot approach to the issue, with inconsistent requirements for congressional districts, state legislative districts and even school boards.

A similar dynamic has played out in Nevada: The state ended prison gerrymandering in congressional and state legislative districts, but left decisions at the city council level up to local governments. In the most recent cycle, Las Vegas counted incarcerated people at their last pre-prison address, and Reno did not.

Some of these asymmetries stem from state legislators’ decision to exempt local governments from the laws they passed. Kathay Feng, an advocate at the voting rights organization Common Cause, said this may have been a tactic in some states to avoid paying the cost of local changes, or to sidestep conflicts with “home rule” laws that give localities wide latitude.

Darby, the Wilmington councilmember, was happy to bring her city in line with the way Delaware draws state legislative districts.

Now, she says she’d like to see governments include incarcerated people in the political process. Delaware currently bars people in prison with felony convictions from voting, and it also disenfranchises thousands of people on probation or parole. The state makes it more difficult to regain voting rights than most in the Northeast.

“How do we take it a step further?” Darby asked. “They need rights to vote — not everybody, but some people who are in prison should still be able to vote and have their voices be heard.”

Currently, only Maine, Vermont and Washington, D.C., allow people in prison to vote. Many Americans held in local jails also retain their right to vote but find it nearly impossible to cast a ballot. Advocates say that this “de facto disenfranchisement” affects the majority of the roughly 445,000 people in American jails who have not been convicted of a crime. A handful of states and counties around the U.S. have made a push to facilitate jail voting, including establishing precincts in jail, but some local officials have resisted such efforts.

As a result, thousands of Americans are counted for the purpose of redistricting where they are detained, increasing that area’s political clout, without the ability to participate in local elections.

And until the Census Bureau changes the way it counts incarcerated people, advocates and elected officials will be forced to address prison gerrymandering one place at a time.

“The city of Wilmington is small, and the population of the prison wasn’t anything crazy,” said Darby, who sponsored the measure to permanently end the practice in the city. “But I thought it was important to make that point.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $31,000 in the next 48 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.