The international climate talks in Egypt — the 27th Conference of Parties to the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, or COP27 — have become a dystopian nightmare: Oil companies, dictators and greenwashers captured the process more effectively than ever.

But there is hope: Alliances are taking shape — between civil society, scientists and labor — that aim to break the fossil fuel companies’ deathly grip on climate policy.

Corporate Capture

This year’s United Nations climate summit, which ends on November 17 at the luxury Sharm el-Sheikh resort, is the first to which oil and gas companies were invited to participate in the official program of events. Rachel Rose Jackson of Corporate Accountability commented that “COP27 looks like a fossil fuel industry trade show.”

At least 636 fossil fuel lobbyists were there, 25 percent more than at last year’s talks in Glasgow. The lobbyists outnumbered the combined delegations of the 10 countries most impacted by climate change, including Pakistan, Bangladesh and Mozambique, research by Corporate Europe Observatory, Corporate Accountability and Global Witness showed.

The world’s largest oil producers strutted their stuff. Saudi Arabia ran an event to promote the “circular carbon economy,” under which carbon capture, hydrogen, and other fossil fuel-based technologies are falsely promoted as “clean.”

Wealth and power were flaunted. Coca-Cola, the world’s top plastic polluter, sponsored the talks. Delegates flew in on private jets: Thirty-six arrived at Sharm el-Sheikh as the summit began, and another 64 flew into Cairo. The Egyptian authorities ignored the international campaign to free dissident Alaa Abd El-Fattah — who is serving a five-year jail sentence for a social media post — and other political prisoners.

Central to the fossil fuel industry’s PR offensive is the new dash for gas, kick-started by the Russian war on Ukraine and Moscow’s decision to limit gas supplies to Europe. For the Gas Exporting Countries Forum, an alliance of 17 big gas producers including Egypt, COP27 was “a great opportunity to make a case for gas in the energy transition.”

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February, plans to build 26 new import terminals for liquefied natural gas (LNG) have been announced in Europe; the EU has signed a deal with Egypt and Israel to support gas extraction in the East Mediterranean Sea; and European politicians have sought gas project deals with African nations.

Once a gas project is decided on, it can take up to 10 years before production starts. So Europe’s supply gap this year and next will be filled, if at all, by existing producers such as Qatar, the U.S. and Australia, not by new projects. The danger is that, over the next decade, those projects will push the world still further from the goal of limiting global heating to 1.5 degrees Celsius (1.5°C) above pre-industrial levels.

The International Energy Agency says that, to hit “net zero” targets, there can be no new gas or oil fields, and that gas demand must be slashed; UN Secretary-General António Guterres said in June that investing in oil or gas production was “delusional.”

Although natural gas produces only about half the carbon emissions per unit of energy that coal does, climate science says it must be phased out. Moreover, leakages of methane (i.e. gas) have been recognized as a significant climate threat: Methane’s greenhouse effect, over a 20-year timespan, is 86 times as powerful as carbon dioxide’s. And yet in May, the European Commission classified natural gas as a “sustainable” source of energy under its investment taxonomy rules, and in September the U.K. government offered new licences for North Sea oil and gas fields. It was these greenwashing, wealthy country governments that, with oil companies, turned COP27 into a climate disaster.

At Sharm el-Sheikh, African governments presented gas projects on the continent as a means of economic development — but they “will not deliver for African communities,” warned Don’t Gas Africa, an alliance of civil society groups that advocate large-scale renewables as opposed to export-focused fossil fuel production.

Nigerian climate justice campaigner Nnimmo Bassey, coordinator of Oilwatch International, denounced the African governments’ pro-gas stance as “ecocide and intergenerational crime” that “perpetuates colonialism and ecological irresponsibility.”

Governments’ Inaction and Civil Society Response

The fossil fuel PR circus at Sharm el-Sheikh has obscured the frightful crisis at the heart of the talks: that the door is closing on the possibility of keeping global heating to 1.5°C, as Climate Action Tracker researchers showed in an authoritative report on climate inaction.

Nations’ current policies will produce global heating of between 2.2°C and 3.4°C by the end of the century, the report showed. Commitments made at last year’s Glasgow talks to toughen up national targets (Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs) have been broken; commitments made to exit from coal have been disrupted; and rich countries have again broken promises to finance the energy transition in the Global South.

In Sharm el-Sheikh, talks about implementing already-inadequate decisions went at snail’s pace. Delegates from outside the rich world fumed at slow progress on Loss and Damage, the principle that rich countries should pay for the billions of dollars in damage already done by climate change — for example, by the floods in Pakistan this summer. Campaigners urged a windfall tax on fossil fuel companies for this purpose.

The fossil fuel companies’ brazen grandstanding, and governments’ acquiescence, has tested the faith of campaign groups, climate scientists, and others in the prospect of top-down solutions to the climate crisis.

Swedish activist Greta Thunberg stayed away from Sharm el-Sheikh, describing the negotiations as “an opportunity for leaders and people in power to get attention, using many different kinds of greenwashing.” Rather than the COP’s incremental steps, “system-wide transformation” is needed, she said at a London book launch, infuriating right-wing commentators and techno-utopians.

But Thunberg was reflecting deeply felt anger among campaign groups, including those who have for years invested hope in the COP process. More than 450 organizations supported a call for a UN Accountability Framework to “end corporate capture”; throw “big polluters” out of the climate talks; require delegates publicly to disclose their interests; ban partnership or sponsorship of talks by the polluters; and ease restrictions on civil society access.

As the climate talks have lurched towards greenwashing, protests and direct actions over governments’ failures are gaining momentum again after being disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Pascoe Sabido, researcher at Corporate Europe Observatory, said:

There is a movement on the streets [about climate change], but it has not been translated into political power. The problem is the power of governments, and their alliance with fossil fuel companies. Until we break open that relationship, there will not be a transition away from fossil fuels.

Outside the Talks

So are the climate talks part of the problem, or part of the solution? It is not only activists who are asking. The authors of the UN Environment Programme’s latest “Emissions Gap Report” described their findings as “testimony to inadequate action on the global climate crisis, and is a call for the rapid transformation of societies.”

There had been “very little progress” since the 2021 Glasgow talks, and governments’ current policies are on track to cause 2.8°C rise in temperature by 2100, the report says. “Multiple major transformations must be initiated in this decade, simultaneously across all [fossil fuel-based technological] systems.”

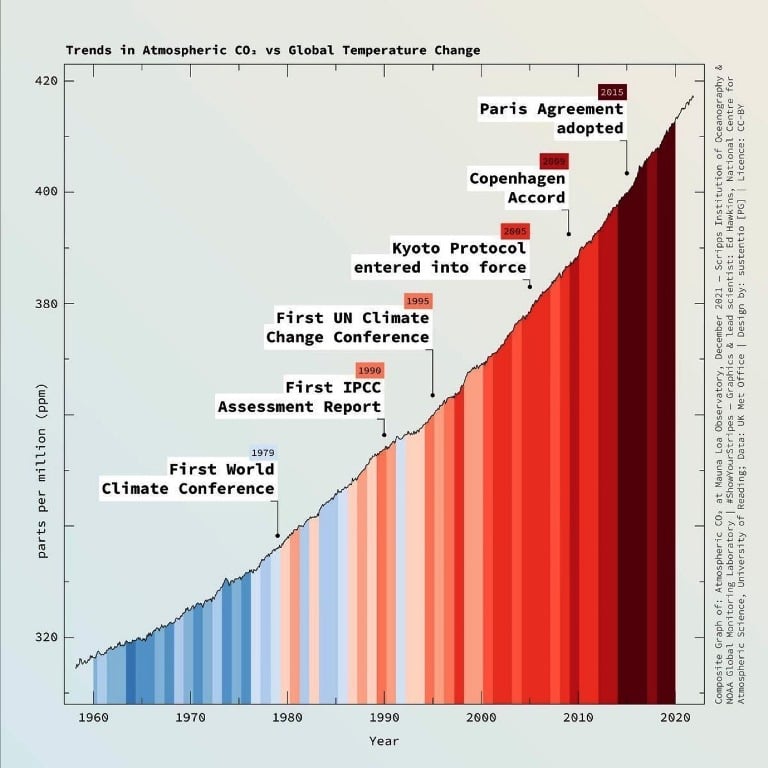

Thirty-plus years of history matters. Prior to the talks in Egypt, climate scientists shared on social media a graph showing the relentless rise in the atmosphere’s carbon dioxide content, from about 360 parts per million (ppm) when the Rio climate treaty was signed in 1992, to 420 ppm now. The inexorable rise in fossil fuel use is the main cause.

The alliance of the world’s most powerful states, who negotiated the climate agreements, is not only unwilling, but also unable, to do what is needed. To prevent dangerous global heating, systems must change — not only technological systems, but economic and social ones. And those governments’ function is to defend and manage those systems, not transform them. Society as a whole will have to deal with climate change, in defiance of those governments.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $33,000 in the next 2 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.