The following excerpt is the author’s prologue to Survival and Conscience: From the Shadows of Nazi Germany to the Jewish Boat to Gaza.

A question runs through this book and asks how two major events of my life, two seemingly diametrically opposed experiences, have influenced one another to shape my opposition to Zionism. This is the story I wish to tell.

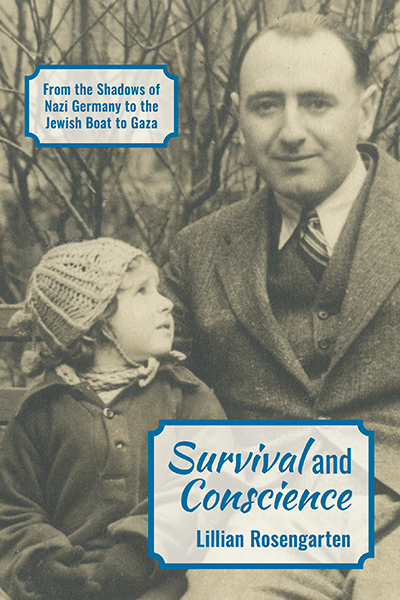

In 1936, my parents, Fritz and Lilli Lebrecht, found a way to leave their beloved Germany to flee the Nazis. Brownshirts had already started to terrorize the lives of Jews, including my parents. It was difficult for my father, who had left months earlier for New York, to leave my mother and I behind in order to obtain a visa that would allow us to emigrate. German Jewish refugees who attempted to flee the Nazi racial laws were not freely given permission to enter the United States for, in the 1930s, there was a strict quota system. One had to face America’s formidable system of immigration laws. Applicants required an American sponsor willing to sign an affidavit of financial support promising the immigrant would not become a public charge and was of good health. In addition, one was required to have a job waiting as well as a place to live. This my father accomplished, and he rescued my mother and their eighteen-month-old toddler: myself. If he had not succeeded, my mother and I could not have survived.

More than seventy years later, in September 2010, I took another equally momentous sea voyage. I was one of seven Jewish passengers who, along with two journalists, set sail across the Mediterranean on a tiny catamaran. We were headed for the shores of Gaza in an attempt to break the siege and express solidarity as Jews against the suffering of Palestinians. The feeling as we sailed across the Mediterranean was one of joyful expectation. I did not imagine that Israeli warships would storm our vessel and that armed commandos would drag us to Ashdod prison to cruelly abort our mission of solidarity and hope. I could not imagine I would be deported from Israel and told I could not return for ten years.

In 1945, when the war against the Nazis ended, I was ten years old and lived with my parents in Jamaica, New York. Throughout my childhood and well into adulthood, I pushed the whole issue of the corruption of Germany by the Nazis to a deeply hidden place, unwilling and unable to identify myself as a German Jew. I was lost. Instead, I assumed my roles as a “good” daughter and a “good” American. Prior to leaving Germany, my family had been well-assimilated into German society as secular, non-religious Jews, like many German Jews who left Germany in the mid- to late 1930s. Being Jewish as a form of organized religion meant nothing to me. As I grew older, I haphazardly identified as a “cultural” Jew. In this way, I could hold on to some vestige of Jewish identification. When I married, politics became my religion, and I continued to bury my identification as a German Jew to a dark place within me, still left unexamined.

Years later, well into my fifties, I made numerous visits to relatives in Israel, refugees also from Germany who supported Israeli politics and lived comfortably. It was then I became aware of another aspect of Israel, a truly disturbing revelation for I, like so many Jews in the world, had idealized this land that I believed was created as a “beacon of light,” a safe haven and land of compassion where refugees everywhere would be welcome. I look back and realize how idealistic was this image I had dreamed about and how naïve. Yet in my heart, I too had longed for a safe homeland.

This life-altering experience came to light when I met a first cousin of my father, who became my mentor and role model as both a critic and a lover of Israel. Hans Lebrecht, a former human rights activist and journalist, opened my eyes to a different Israel that for me was profoundly troubling. I had not been aware until then of Israel’s insatiable hunger for land, or the racism I observed towards Palestinians, Sephardic Jews, Bedouins, and later, African asylum-seekers seeking work and political freedom. Awoken by Hans from my dream of a democratic, safe Israel, my love for the country had become tainted. How could Israel have built socialist-style communal living on someone else’s land? It did not make sense. I grew agitated and heard half-remembered echoes of coarse shouts that I had suppressed for years: “Refugees, reviled Jews who must be cleansed out of Germany and the rest of Europe!” or, as heard from a neighbor in our family apartment in Jamaica, Queens, “Those dirty Jews upstairs should have been killed by Hitler!”

I wanted to love Israel, where I had felt safe, free, and happy to be Jewish. I loved the kibbutzim – the spirit of collective socialism and the pride of the people – as well as the beauty of the country. However, my identification as a refugee became a driving force in my empathy with the victimization and struggle of Palestinians; 700,000 Palestinians were thrown out in 1948, and those who have not died remain as homeless refugees. Remaining Palestinians live under a brutal occupation in the West Bank and Gaza. I am a witness. It has been a painful soul-searching journey for me to recognize and understand Israel as an oppressor nation. In addition, my curiosity concerning victims who had become victimizers also contributed to the birth of this book.

I ache for Israel, for its path of blind destruction that continues after five decades and three generations following its birth in 1948 to become an apartheid state separated by a nine-foot-high, 403-mile-long wall to keep out the “enemy.” I am haunted by the question, after forty-eight years of apartheid, how can the occupation be ended? There is a sign in Hebron, “There is no Palestine and there never will be.”

How is it possible that Jews, who themselves and their ancestors before them have been victims of the worst nightmare of the Final Solution, can turn away in blind denial? How can we forget the children, born into hate, living still in crowded camps that are breeding grounds for endless violence and conflict? It is all so familiar.

In 2010–2011, it was difficult to observe the demonization of Judge Richard Goldstone, a jurist and proud South-African Jew who set out to investigate international human rights violations during Operation Cast Lead in Gaza. He concluded that both Israel and Hamas had committed war crimes. Here was an opportunity to reflect and discuss, to have debates, and to engage in further investigations on both sides. But his report was squelched for the most part by Israel and the United States. He was ridiculed and humiliated as “a self-hating Jew,” when nothing could be further from the truth.

It is a complicated question, how a hunted people have become hunters, how victims became victimizers. It may well be that it is the Israelis who feel the most persecuted; many of them still carry the weight of generations of hatred inflicted on them, and surely it has shaped the direction of their society. In my view, this hatred has been projected onto the “Other” – a Palestinian or a dissenting Jew.

In order to end the cycle of endless suffering for Jews and Palestinians, the Israeli powers-that-be can only benefit from self-examination, from honest and open dialogue including, of course, with the mistrusted “enemy.” The goal must be mutual commonality and an end to demonizing the “Other.” Left unexamined, the projection of hate onto those with other views and with diverse political persuasions succeeds only in perpetuating endless suffering and hatred that festers, destroys, and grows more virulent with each new generation.

(Image: Just World Books)I was carried out of Nazi Germany in the arms of my mother. This exodus, although not in my conscious memory, planted very early in my childhood seeds of rootlessness and feelings of a profound disconnect. So alone and apart was I, altogether different and awkward, yet not able to grasp the reasons for my alienation. Remnants of the experience of having one’s roots pulled up violently have remained with me always. Then, as a child growing up, I longed to be American and not German. For decades, I denied my background, ignoring it as well as my refugee relatives. This unwanted part of me remained buried for decades, an amorphous, unexamined connection to my German homeland. That I felt different was perhaps a prophetic sign, for one day I would overcome the wish to be rid of all that was German. I would, in fact, be hungry to know my German-Jewish self. In my earlier years, fragments of loss, death, and fragility played with my imagination in my dreams.

(Image: Just World Books)I was carried out of Nazi Germany in the arms of my mother. This exodus, although not in my conscious memory, planted very early in my childhood seeds of rootlessness and feelings of a profound disconnect. So alone and apart was I, altogether different and awkward, yet not able to grasp the reasons for my alienation. Remnants of the experience of having one’s roots pulled up violently have remained with me always. Then, as a child growing up, I longed to be American and not German. For decades, I denied my background, ignoring it as well as my refugee relatives. This unwanted part of me remained buried for decades, an amorphous, unexamined connection to my German homeland. That I felt different was perhaps a prophetic sign, for one day I would overcome the wish to be rid of all that was German. I would, in fact, be hungry to know my German-Jewish self. In my earlier years, fragments of loss, death, and fragility played with my imagination in my dreams.

My father, an assimilated Jew, considered himself more German than Jewish. He told me the Zionist movement had little impact on his family and other wealthy German Jews who identified themselves as an integral part of German society. They could have been called German nationalists, for they loved their country. But with the establishment of the Nuremburg laws, non-Jewish Germans started to refer to German Jews as foreigners.

I have struggled to organize the sequence of my personal and political lives, which remain inextricably intertwined. To do so has required that I scrutinize my life unflinchingly in order to examine deeply personal traumas with openness and honesty.

I am thinking about one Saturday evening in April 1999. I walked to Varick Street in Greenwich Village, New York. I was going to see a movie, Wind Horse. Wind horses are mystical creatures on whose backs Tibetans send prayers to dead ancestor spirits. Among the prayers are hopes for freedom. Wind Horse was filmed in Tibet and smuggled out. I shall not forget images of a Buddhist nun, tortured and subsequently dying in the arms of her family. I speak of this for it is another cruel example of man’s inhumanity to man, repression and destruction, the occupation of Tibetans by the Chinese. The film never showed up again after it closed a few days later.

Some months later at a poetry reading, I heard the despair of a Cambodian physician once imprisoned with his pregnant wife in the killing fields of the Khmer Rouge. His words sent chills through the large room; his voice, in part a high-pitched scream, told us of the birth of his twin daughters, pulled out of his wife’s womb by two Khmer guards as she lay on the dirt ground. Not long after he held them both in his arms, he threw them into the Mekong River as he sang a song for their souls and hoped they had been laid to rest. Only he survived to tell the story of another Holocaust. I cannot put into words how this man’s suffering is every man’s suffering – and if we cannot fathom this, then surely humanity is lost.

As I walked down Canal Street that evening in 1999, I thought about the imminent anniversary of my father’s suicide, a result of repression and oppression of a different sort: personal family dynamics. My father, politically oppressed himself, in turn oppressed his family. My parents left a country they loved and where they had thrived. They had dreams of their own and lived a rich, fulfilled life until Hitler assumed power. Part of a large, well-connected family, they had been young, energetic, and hopeful. But there was a dark side as well, for shortly after the Nuremberg Laws were passed, my paternal grandmother committed suicide as did my maternal grandfather. Depression and vicious racist laws, the destruction of their homeland, as well as the forced uprooting of a once intact family, must be understood as a driving force for their suicides, which I have no doubt were statements of deep despair.

The dark shadows of my refugee experience, in combination with a difficult and lonely childhood, make clearer my passionate quest (much later in my adult life) to break down barriers and artificial boundaries and to foster understanding between people. As a child, my voice was silenced. There was little room for self-expression. There were rules to be followed, rigid codes of behavior; and I was a very “good” girl who followed rules. I look back and recognize how Germanic my parents and their rules were! I felt I had no choice but to obey. When Hitler became chancellor, much of the German population were “good” German followers of the Nazi edicts, and rules had to be obeyed meticulously. In truth, my father, a good German, behaved like a little dictator in his own home. I was criticized from an early age and learned to keep my mouth shut. I felt caged as a child, a bird struggling (but seldom daring) to fly, to be free, and to find my own voice.

I know now that I was ashamed of my German family. I could only receive Mommy’s love when I was a “good” girl who became what my mother wanted me to be, an extension of herself. Any form of rebellion created anxiety in my mother and reinforced a perception of me as a “bad” girl. Later in a difficult marriage, I was an unprepared parent, lost and in search of myself. I once had three children. My eldest son, Philip, died of a drug overdose in 1996. His death brought me to an awareness of the impermanence of life. This book was also born from these experiences that helped to shape who I am today.

How did I find my voice after such a repressed childhood? What drove my decision, when I was in my seventies, to be a passenger on the Jewish Boat to Gaza? How is it that as a refugee from Nazi Germany, I have come to be a critic of Israel?

It is not beyond comprehension to understand the policies of the Israeli government in light of Jewish history under the Nazi pogroms. We know Jews have suffered and have been victims. Is it that mentality behind the walls Israel has built? Are they still “victims” of paranoia and fear? Nationalism revisited is now twisted into a parody of the Nazi credo, “Deutschland über alles,” extolling Germany over all others, with only pure Germans as inhabitants. “Get rid of the undesirables who are beneath contempt!” I must not make such a comparison, you may say. Yet I know that I must, for I fear a Jewish State that belongs only to Jews is a dangerous road. Many older generation Jews, their own psychological work left undone, carry within them deep scars of the Nazi Holocaust that is imprinted and lives on in the form of guilt, victimhood, and what I consider an irrational fear of another Holocaust brought on by exploding anti-Semitism in the world. Dwell upon the following words I heard recently from a group of Jews who are strong supporters of Zionism and their political agenda: “Without Israel there would not be a safe Jew in the world.” Those fears have yet to be confronted within the context of Zionist racist ideology.

The cycle of paranoia and abuse is playing out its destructive course: this is how I understand Palestinians as the last victims of the Holocaust. It is painful to attempt to understand what drove the Zionist movement in Israel/Palestine over the last sixty-seven years to continue on its determined path to separate itself, to have a Jewish state acquired through brute force and occupation.

I have divided this book into two parts, though in truth, they are one. First there is a personal story, my life as it was, presenting the dark shadows that surrounded our refugee experience, my parents’ unhappiness, fragile moments, secrets, and a difficult, lonely childhood. Then, beginning in my fifties, I traveled to remote corners of the world, in search of cultures unscathed by modernity, missionizing, or Western development. My travels showed me unique cultures and provided an amazing recognition of the similarities of all beings, despite external differences. Years later, I would find the same human connection with Palestinians in the squalid, rotten refugee camps of Gaza. Their faces haunt me.

Part Two begins with my first visits to Israel as a politically unengaged Jewish woman who fell in love with the country. I gradually awakened to political realities and the most difficult question that remains to be discussed freely, without fear of censure: how can apartheid and a Jewish State survive together under the name of a democratic Jewish State? This immense question ultimately informed my decision to be a passenger on the Jewish Boat to Gaza. It was after our failed attempt to break the siege of Gaza and my imprisonment that I had an opportunity to visit Frankfurt, the city of my birth. What I found there provided a new set of surprises.

The reflections and conclusions in this book were first born in a place of disquiet and fear. It has been difficult to find the courage to speak out against a system that, in my view, attempts to destroy the very fabric of what it means to be Jewish and a humanist. My deepest belief holds that peace can come only when Israel/Palestine are a unified country living under mutual democracy, with dignity and equal rights. I invite you to set sail with me here, on this journey of survival and conscience.

Copyright (2015) of Lillian Rosengarten. Not to be reposted without the permission of the publisher, Just World Books.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.